Great Satan" Vs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hostage Crisis in Iran May Or May Not Have Been a Proportionate Response

AP United States History Document-Based Question Note: The following document is adopted from the AP U.S. History College Board Examples United States History Section II Total Time – 1 hour, 30 minutes Question 1 (Document-Based Question) Suggested reading period: 15 minutes Suggested writing period: 40 minutes This question is based on the accompanying documents. The documents have been edited for the purpose of this exercise. In your response you should do the following: Thesis: Present a thesis that makes a historically defensible claim and responds to all parts of the question. The thesis must consist of one or more sentences located in one place, either in the introduction or in the conclusion. Argument Development: Develop and support a cohesive argument that recognizes and accounts for historical complexity by explicitly illustrating relationships among historical evidence such as contradiction, corroboration, and/or qualification. Use of Documents: Utilize the content of at least six documents to support the stated thesis or a relevant argument. Sourcing the Documents: Explain the significance of the author’s point of view, author’s purpose, historical context, and/or audience for at least four documents. Contextualization: Situate the argument by explaining the broader historical events, developments, or processes immediately relevant to the question. Outside Evidence: Provide an example or additional piece of specific evidence beyond those found in the documents to support or qualify the argument. Synthesis: Extend the argument by explaining the connections between the argument and one of the following o A development in a different historical period, situation, era, or geographical area. o A course theme and/or approach to history that is not the focus of the essay (such as political, economic, social, cultural, or intellectual history). -

Timeline of Iran's Foreign Relations Semira N

Timeline of Iran's Foreign Relations Semira N. Nikou 1979 Feb. 12 – Syria was the first Arab country to recognize the revolutionary regime when President Hafez al Assad sent a telegram of congratulations to Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The revolution transformed relations between Iran and Syria, which had often been hostile under the shah. Feb. 14 – Students stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, but were evicted by the deputy foreign minister and Iranian security forces. Feb. 18 – Iran cut diplomatic relations with Israel. Oct. 22 – The shah entered the United States for medical treatment. Iran demanded the shah’s return to Tehran. Nov. 4 – Students belonging to the Students Following the Imam’s Line seized the U.S. Embassy in Tehran. The hostage crisis lasted 444 days. On Nov. 12, Washington cut off oil imports from Iran. On Nov. 14, President Carter issued Executive Order 12170 ordering a freeze on an estimated $6 billion of Iranian assets and official bank deposits in the United States. March – Iran severed formal diplomatic ties with Egypt after it signed a peace deal with Israel. Three decades later, Egypt was still the only Arab country that did not have an embassy in Tehran. 1980 April 7 – The United States cut off diplomatic relations with Iran. April 25 – The United States attempted a rescue mission of the American hostages during Operation Eagle Claw. The mission failed due to a sandstorm and eight American servicemen were killed. Ayatollah Khomeini credited the failure to divine intervention. Sept. 22 – Iraq invaded Iran in a dispute over the Shatt al-Arab waterway. -

Continuation of the National Emergency with Respect to Iran

1 116th Congress, 1st Session – – – – – – – – – – – – – House Document 116–79 CONTINUATION OF THE NATIONAL EMERGENCY WITH RESPECT TO IRAN COMMUNICATION FROM THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES TRANSMITTING NOTIFICATION THAT THE NATIONAL EMERGENCY WITH RESPECT TO IRAN, DECLARED IN EXECUTIVE ORDER 12170 OF NOVEMBER 14, 1979, IS TO CONTINUE IN EFFECT BEYOND NOVEMBER 14, 2019, PURSUANT TO 50 U.S.C. 1622(d); PUBLIC LAW 94–412, SEC. 202(d); (90 STAT. 1257) NOVEMBER 13, 2019.—Referred to the Committee on Foreign Affairs and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 99–011 WASHINGTON : 2019 VerDate Sep 11 2014 05:28 Nov 15, 2019 Jkt 099011 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4012 Sfmt 4012 E:\HR\OC\HD079.XXX HD079 Sspencer on DSKBBXCHB2PROD with REPORTS E:\Seals\Congress.#13 VerDate Sep 11 2014 05:28 Nov 15, 2019 Jkt 099011 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 4012 Sfmt 4012 E:\HR\OC\HD079.XXX HD079 Sspencer on DSKBBXCHB2PROD with REPORTS To the Congress of the United States: Section 202(d) of the National Emergencies Act (50 U.S.C. 1622(d)) provides for the automatic termination of a national emer- gency unless, within 90 days before the anniversary date of its dec- laration, the President publishes in the Federal Register and trans- mits to the Congress a notice stating that the emergency is to con- tinue in effect beyond the anniversary date. In accordance with this provision, I have sent to the Federal Register for publication the en- closed notice stating that the national emergency with respect to Iran declared in Executive Order 12170 of November 14, 1979, is to continue in effect beyond November 14, 2019. -

Bulletin De Liaison Et D'information

INSTITUT KURD E DE PARIS Bulletin de liaison et d’information N°382 JANVIER 2017 La publication de ce Bulletin bénéficie de subventions des Ministères français des Affaires étrangères et de la Culture ————— Ce bulletin paraît en français et anglais Prix au numéro : France: 6 € — Etranger : 7,5 € Abonnement annuel (12 numéros) France : 60 € — Etranger : 75 € Périodique mensuel Directeur de la publication : Mohamad HASSAN Maquette et mise en page : Şerefettin ISBN 0761 1285 INSTITUT KURDE, 106, rue La Fayette - 75010 PARIS Tél. : 01- 48 24 64 64 - Fax : 01- 48 24 64 66 www.fikp.org E-mail: [email protected] Bulletin de liaison et d’information de l’Institut kurde de Paris N° 382 janvier 2017 • ROJAVA: MALGRÉ LA PRÉSENCE MILITAIRE TURQUE ET LES INCERTITUDES DIPLOMATIQUES, LES FDS POURSUIVENT LEUR AVANCÉE VERS RAQQA • KURDISTAN D’IRAK: DAECH RECULE À MOSSOUL, TENSIONS INTERNES AU KURDISTAN COMME EN IRAK • TURQUIE: JOURNALISTES, ÉCRIVAINS, ENSEI - GNANTS, ÉLUS HDP… LA RÉPRESSION GÉNÉRALI - SÉE, AVANT-GOÛT DE LA NOUVELLE CONSTITU - TION ? • TURQUIE: LE CO-PRÉSIDENT DU HDP RÉCUSE À SON PROCÈS TOUT APPEL À LA VIOLENCE ET ACCUSE LES DIRIGEANTS AKP D’ÊTRE RESPON - SABLES DU BAIN DE SANG ROJAVA: MALGRÉ LA PRÉSENCE MILITAIRE TURQUE ET LES INCERTITUDES DIPLOMA - TIQUES, LES FDS POURSUIVENT LEUR AVANCÉE VERS RAQQA ’opération turque «Bouclier allié principal en Syrie la Turquie Times révélait que la Turquie avait de l’Euphrate» s’est pour - plutôt que les Forces démocra - systématiquement retardé l'appro - suivie dans le nord de la tiques syriennes, dont le noyau est bation des missions aériennes L Syrie, notamment l’at - constitué des YPG, les combattants américaines décollant de la base… taque sur al-Bab, tenue kurdes du PYD (Parti de l’union Reflétant l’évolution complexe des par Daech, mais où l’armée turque démocratique), l’ennemi quasi- relations politiques entre Turquie, veut surtout devancer les obsessionnel de M. -

IN IRAN Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green Fulfillment

HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF BROADCASTING IN IRAN Bigan Kimiachi A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY June 1978 © 1978 BI GAN KIMIACHI ALL RIGHTS RESERVED n iii ABSTRACT Geophysical and geopolitical pecularities of Iran have made it a land of international importance throughout recorded history, especially since its emergence in the twentieth century as a dominant power among the newly affluent oil-producing nations of the Middle East. Nearly one-fifth the size of the United States, with similar extremes of geography and climate, and a population approaching 35 million, Iran has been ruled since 1941 by His Majesty Shahanshah Aryamehr. While he has sought to restore and preserve the cultural heritage of ancient and Islamic Persia, he has also promoted the rapid westernization and modernization of Iran, including the establishment of a radio and television broadcasting system second only to that of Japan among the nations of Asia, a fact which is little known to Europeans or Americans. The purpose of this study was to amass and present a comprehensive body of knowledge concerning the development of broadcasting in Iran, as well as a review of current operations and plans for future development. A short survey of the political and spiritual history of pre-Islamic and Islamic Persia and a general survey of mass communication in Persia and Iran, especially from the Il iv advent of the telegraph is presented, so that the development of broadcasting might be seen in proper perspective and be more fully appreciated. -

Iran Chamber of Commerce,Industries and Mines Date : 2008/01/26 Page: 1

Iran Chamber Of Commerce,Industries And Mines Date : 2008/01/26 Page: 1 Activity type: Exports , State : Tehran Membership Id. No.: 11020060 Surname: LAHOUTI Name: MEHDI Head Office Address: .No. 4, Badamchi Alley, Before Galoubandak, W. 15th Khordad Ave, Tehran, Tehran PostCode: PoBox: 1191755161 Email Address: [email protected] Phone: 55623672 Mobile: Fax: Telex: Membership Id. No.: 11020741 Surname: DASHTI DARIAN Name: MORTEZA Head Office Address: .No. 114, After Sepid Morgh, Vavan Rd., Qom Old Rd, Tehran, Tehran PostCode: PoBox: Email Address: Phone: 0229-2545671 Mobile: Fax: 0229-2546246 Telex: Membership Id. No.: 11021019 Surname: JOURABCHI Name: MAHMOUD Head Office Address: No. 64-65, Saray-e-Park, Kababiha Alley, Bazar, Tehran, Tehran PostCode: PoBox: Email Address: Phone: 5639291 Mobile: Fax: 5611821 Telex: Membership Id. No.: 11021259 Surname: MEHRDADI GARGARI Name: EBRAHIM Head Office Address: 2nd Fl., No. 62 & 63, Rohani Now Sarai, Bazar, Tehran, Tehran PostCode: PoBox: 14611/15768 Email Address: [email protected] Phone: 55633085 Mobile: Fax: Telex: Membership Id. No.: 11022224 Surname: ZARAY Name: JAVAD Head Office Address: .2nd Fl., No. 20 , 21, Park Sarai., Kababiha Alley., Abbas Abad Bazar, Tehran, Tehran PostCode: PoBox: Email Address: Phone: 5602486 Mobile: Fax: Telex: Iran Chamber Of Commerce,Industries And Mines Center (Computer Unit) Iran Chamber Of Commerce,Industries And Mines Date : 2008/01/26 Page: 2 Activity type: Exports , State : Tehran Membership Id. No.: 11023291 Surname: SABBER Name: AHMAD Head Office Address: No. 56 , Beside Saray-e-Khorram, Abbasabad Bazaar, Tehran, Tehran PostCode: PoBox: Email Address: Phone: 5631373 Mobile: Fax: Telex: Membership Id. No.: 11023731 Surname: HOSSEINJANI Name: EBRAHIM Head Office Address: .No. -

Read the Introduction

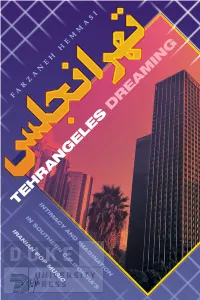

Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING IRANIAN POP MUSIC IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION TEHRANGELES DREAMING Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S IRANIAN POP MUSIC Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Portrait Text Regular and Helvetica Neue Extended by Copperline Book Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Hemmasi, Farzaneh, [date] author. Title: Tehrangeles dreaming : intimacy and imagination in Southern California’s Iranian pop music / Farzaneh Hemmasi. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019041096 (print) lccn 2019041097 (ebook) isbn 9781478007906 (hardcover) isbn 9781478008361 (paperback) isbn 9781478012009 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Music. | Popular music—California—Los Angeles—History and criticism. | Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Ethnic identity. | Iranian diaspora. | Popular music—Iran— History and criticism. | Music—Political aspects—Iran— History—20th century. Classification:lcc ml3477.8.l67 h46 2020 (print) | lcc ml3477.8.l67 (ebook) | ddc 781.63089/915507949—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041096 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041097 Cover art: Downtown skyline, Los Angeles, California, c. 1990. gala Images Archive/Alamy Stock Photo. To my mother and father vi chapter One CONTENTS ix Acknowledgments 1 Introduction 38 1. The Capital of 6/8 67 2. Iranian Popular Music and History: Views from Tehrangeles 98 3. Expatriate Erotics, Homeland Moralities 122 4. Iran as a Singing Woman 153 5. A Nation in Recovery 186 Conclusion: Forty Years 201 Notes 223 References 235 Index ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There is no way to fully acknowledge the contributions of research interlocutors, mentors, colleagues, friends, and family members to this book, but I will try. -

Iran COI Compilation September 2013

Iran COI Compilation September 2013 ACCORD is co-funded by the European Refugee Fund, UNHCR and the Ministry of the Interior, Austria. Commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Division of International Protection. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author. ACCORD - Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation Iran COI Compilation September 2013 This report serves the specific purpose of collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. It is not intended to be a general report on human rights conditions. The report is prepared on the basis of publicly available information, studies and commentaries within a specified time frame. All sources are cited and fully referenced. This report is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Every effort has been made to compile information from reliable sources; users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. © Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD An electronic version of this report is available on www.ecoi.net. Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD Wiedner Hauptstraße 32 A- 1040 Vienna, Austria Phone: +43 1 58 900 – 582 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.redcross.at/accord ACCORD is co-funded by the European Refugee Fund, UNHCR and the Ministry of the Interior, Austria. -

Human Rights Without Frontiers Forb Newsletter | Iran

Table of Contents • News about Baha’is and Christians in Iran in December • European government ministers and parliamentarians condemn denial of higher education to Baha’is in Iran • News about Baha’is and Christians in Iran in November • UN passes resolution condemning human rights violations in Iran • House-church leaders acquitted of ‘acting against national security’ • Four Christians given combined 35 years in prison • Second Christian convert flogged for drinking Communion wine • Christian convert’s third plea for retrial rejected • Christian homes targeted in coordinated Fardis raids • Tehran church with giant cross demolished • News about Baha’is in Iran in October • Iranian Christian convert lashed 80 times for drinking Communion wine • Christian convert among women prisoners of conscience to describe ‘white torture’ • News about Baha’is in Iran in September • Christian converts’ adopted child to be removed from their care • Christian convert released on bail after two months in prison • Iran’s secular shift: new survey reveals huge changes in religious beliefs • Christian converts leave Iran, facing combined 35 years in prison • Iranian church leaders condemn UK bishops’ endorsement of opposition group • ‘First movie ever to address underground Christian movement in Iran’ • Survey supports claims of 1 million Christian converts in Iran • News about Baha’is in Iran in August • Joseph Shahbazian released on bail after 54 days • Iran’s religious minority representatives: surrender to survive • Iranian-Armenian Christian prisoner’s -

Karachi KATRAK BANDSTAND, CLIFTON PHOTO by KHUDABUX ABRO

FEZANA PAIZ 1377 AY 3746 ZRE VOL. 22, NO. 3 FALL/SEPTEMBER 2008 MahJOURJO Mehr-Avan-Adar 1377 (Fasli) G Mah Ardebehest-Khordad-Tir 1378 AY (Shenshai)N G Mah Khordad-Tir-AmardadAL 1378 AY (Kadmi) “Apru” Karachi KATRAK BANDSTAND, CLIFTON PHOTO BY KHUDABUX ABRO Also Inside: 2008 FEZANA AGM in Westminster, CA NextGenNow 2008 Conference 10th Anniversary Celebrations in Houston A Tribute to Gen. Sam Manekshaw PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 22 No 3 Fall 2008, PAIZ 1377 AY 3746 ZRE President Bomi V Patel www.fezana.org Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor 2 Editorial [email protected] Technical Assistan: Coomi Gazdar Dolly Dastoor Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, 3 Message from the President [email protected] 5 FEZANA Update Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, www.khanizadeh.info 6 Financial Report Cover design: Feroza Fitch, [email protected] 35 APRU KARACHI 50 Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia Columnists: Hoshang Shroff:: [email protected] Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi : 56 Renovations of Community Places of [email protected] Fereshteh Khatibi:: [email protected] Worship-Andheri Patel Agiary Behram Panthaki::[email protected] Behram Pastakia: [email protected] 78 In The News Mahrukh Motafram: [email protected] Nikan Khatibi: [email protected] 92 Interfaith /Interalia Copy editors: R Mehta, V Canteenwalla 99 North American Mobeds’ Council Subscription Managers: Kershaw Khumbatta : 106 Youthfully -

Cinema As an Alternative Media: Offside by Jafar Panahi

1 Cinema as an Alternative Media: Offside By Jafar Panahi Hasan Gürkan* ABSTRACT This study inquires whether cinema is an alternative media or not. In our age, when the mainstream media2 is dominating the entire world, new types of media such as the internet can alternatively serve beyond the traditional mass media .Where does the cinema, the seventh art, stand against the existing order and status quo? To what extent is it an alternative means of showing the condition of the minorities in a society? This study addresses to the status of women, who are condemned to a secondary status in Iran and who can be categorized as a emphasizing the fact that ,(2006 ,آف سای د) minority, through the film Offside by Jafar Panahi minority media reflects the status of political – social minorities. Offside by Panahi is an alternative voice of women in Iran, and considered a milestone in Iran‘s minority media as women are seen as a minority in Iran. Keywords: alternative media, minority media, women as minority, alternative cinema Introduction Mass media influences the lives of people, creating special worlds of information, emotions, thoughts, entertainment, curiosity, excitement and many other elements. These dream worlds created by the mass media, develop in parallel with the spirit of capitalism. Media creates its own majority and minorities, making the masses get used to it. Trying to see the situation in a country through the images of mass media and the pictures which are most likely nothing like the truth, people are led to think that those shown as the majority by the media are indeed the majority and those looked down upon and denigrated by the media are the minority. -

Executive Order 13382, "Blocking Property Of

Executive Order 13382, "Blocking Property of Weapons of Mass Destruction Proliferators and Their Supporters"; the Weapons of Mass Destruction Trade Control Regulations (Part 539 of Title 31, C.F.R); and the Highly Enriched Uranium (HEU) Agreement Assets Control Regulations (Part 540 of Title 31, C.F.R) INTRODUCTION - The Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) implements three distinct EXECUTIVE ORDER 13382, “BLOCKING PROPERTY sanctions programs designed to combat the proliferation of OF WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION weapons of mass destruction (WMD). The requirements under PROLIFERATORS AND THEIR SUPPORTERS” each of the programs are different. Each program is described in further detail in this brochure, but they can be summarized SUMMARY OF EXECUTIVE ORDER - Executive Order as follows: 13382 of June 28, 2005 (E.O. 13382), takes additional steps to deal with the national emergency declared in Executive Order • Executive Order 13382 of June 28, 2005, blocks the 12938 of November 14, 1994 (see below), with respect to the property of persons engaged in proliferation activities proliferation of WMD and the means of delivering them. The and their support networks. OFAC administers this Executive Order blocks the property of specially designated blocking program, which initially applied to eight WMD proliferators and members of their support networks. organizations in North Korea, Iran, and Syria. The action effectively denies those parties access to the U.S. Treasury, together with the Department of State, is financial and commercial systems. The program is authorized to designate additional WMD proliferators administered by OFAC. and their supporters under the new authorities provided by this Executive Order.