God and Man in Tehran: Contending Visions of the Divine from The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GOVT-PUNJAB Waitinglist Nphs.Pdf

WAITING LIST SUMMARY DATE & TIME 20-04-2021 02:21:11 PM BALLOT CATEGORY GOVT-PUNJAB TOTAL WAITING APPLICANTS 8711 WAITING LIST OF APPLICANTS S No. Receipt ID Applicant Name Father Name CNIC 1 27649520 SHABAN ALI MUHAMMAD ABBAS ADIL 3520106922295 2 27649658 Waseem Abbas Qalab Abbas 3520113383737 3 27650644 Usman Hiader Sajid Abbasi 3650156358657 4 27651140 Adil Baig Ghulam Sarwar 3520240247205 5 27652673 Nadeem Akhtar Muhammad Mumtaz 4220101849351 6 27653461 Imtiaz Hussain Zaidi Shasmshad Hussain Zaidi 3110116479593 7 27654564 Bilal Hussain Malik tasadduq Hussain 3640261377911 8 27658485 Zahid Nazir Nazir Ahmed 3540173750321 9 27659188 Muhammad Bashir Hussain Muhammad Siddique 3520219305241 10 27659190 IFTIKHAR KHAN SHER KHAN 3520226475101 ------------------- ------------------- ------------------- ------------------- Director Housing-XII (LDAC NPA) Director Finance Director IT (I&O) Chief Town Planner Note: This Ballot is conducted by PITB on request of DG LDA. PITB is not responsible for any data Anomalies. Ballot Type: GOVT-PUNJAB Date&time : Tuesday, Apr 20, 2021 02:21 PM Page 1 of 545 WAITING LIST OF APPLICANTS S No. Receipt ID Applicant Name Father Name CNIC 11 27659898 Maqbool Ahmad Muhammad Anar Khan 3440105267405 12 27660478 Imran Yasin Muhammad Yasin 3540219620181 13 27661528 MIAN AZIZ UR REHMAN MUHAMMAD ANWAR 3520225181377 14 27664375 HINA SHAHZAD MUHAMMAD SHAHZAD ARIF 3520240001944 15 27664446 SAIRA JABEEN RAZA ALI 3110205697908 16 27664597 Maded Ali Muhammad Boota 3530223352053 17 27664664 Muhammad Imran MUHAMMAD ANWAR 3520223937489 -

Rsis Working Papers

No. 125 Thinking Ahead: Shi’ite Islam in Iraq and its Seminaries (hawzah ‘ilmiyyah) Christoph Marcinkowski S. Rajaratnam School of international Studies Singapore 25 April 2007 With Compliments This Working Paper series presents papers in a preliminary form and serves to stimulate comment and discussion. The views expressed are entirely the author’s own and not that of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies The S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) was established in January 2007 as an autonomous School within the Nanyang Technological University. RSIS’s mission is to be a leading research and graduate teaching institution in strategic and international affairs in the Asia Pacific. To accomplish this mission, it will: • Provide a rigorous professional graduate education in international affairs with a strong practical and area emphasis • Conduct policy-relevant research in national security, defence and strategic studies, diplomacy and international relations • Collaborate with like-minded schools of international affairs to form a global network of excellence Graduate Training in International Affairs RSIS offers an exacting graduate education in international affairs, taught by an international faculty of leading thinkers and practitioners. The Master of Science (MSc) degree programmes in Strategic Studies, International Relations, and International Political Economy are distinguished by their focus on the Asia Pacific, the professional practice of international affairs, and the cultivation of academic depth. Over 120 students, the majority from abroad, are enrolled in these programmes. A small, select Ph.D. programme caters to advanced students whose interests match those of specific faculty members. RSIS also runs a one-semester course on ‘The International Relations of the Asia Pacific’ for undergraduates in NTU. -

Landslide Zonation in Fasham Area of Tehran Province (Iran) Abstract Introduction

LANDSLIDE ZONATION IN FASHAM AREA OF TEHRAN PROVINCE (IRAN) Shadi Khoshdoni Farahani, Assoc.Prof.Dr.Md Nor Kamarudin, Dr. Mojgan Zarei Nejad Faculty of Geoinformation Science and Engineering, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia 81300 Skudai, Johor, Malaysia Email: [email protected] Faculty of Geoinformation Science and Engineering, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia 81300 Skudai, Johor , Malaysia Email: [email protected] GIS Center, Solvegatan 12, 223 62 Lund, Lund University, Sweden Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Tehran province which encircles the capital of the Islamic Republic of Iran is highly momentous from the politico- socio-economic-cultural aspects. This significance has instigated the implementation of the geological, geographical and climatological studies in this state in a comprehensive and precise manner. Fasham district in the north eastern part of Tehran province which is a geologically and geographically area has been opted out in this research for semi- detailed studies. the case studied in this research is the landslide in Fasham area. Iran is one of the highly landslide prone countries due to its particular geological, topographical and climatological conditions. Heavy financial lost are reported each year due to the landslide occurrence. The transpiration of these landslides occasionally brings about other death tolls and financial lost originating from earthquakes. Some of the factors affecting this phenomenon are as follows: the alteration of the slope amplitude, geotechnical and litho logical circumstances, earthquake and trembling, tectonics motions, structural alterations, pluvial effects and snow thawing, the extermination of the vegetation, land utilization alteration. The zone under studied is prone to landslide due to various reasons such as possessing special geological conditions and special geographical position. -

Active Tectonics of Tehran Area, Iran

J. Basic. Appl. Sci. Res., 2(4)3805-3819, 2012 ISSN 2090-4304 Journal of Basic and Applied © 2012, TextRoad Publication Scientific Research www.textroad.com Active Tectonics of Tehran Area, Iran Mehran Arian1 *, Nooshin Bagha2 1Associate professor, Department of Geology, Science and Research branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran 2Ph.D.Student, Department of Geology, Science and Research branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran ABSTRACT Tehran area (with 2398.5 km2 area) extended from the east of Damavand volcano to the west of Karaj city. This area is a major part of Tehran province and according to geologic division is a minor part of Alborz zone. This area is under compressive stress and shortening that caused by Arabia – Eurasia Convergence. This situation has confirmed by dominant existence of folded structures and thrust fault system. We have investigated geologic hazards of Tehran area, because this area is the most strategic part of Iran. The major faults have been investigated and have not been found any evidences to existence of north and south Rey faults. In the other hand, active tectonic of this area has been investigated and Mosha fault has been introduced as the most active fault. The high seismic potential has been distinguished by integration of structural geology and active tectonic studies. The evaluation of movement potential of the main faults in the current tectonic regime shows the North Tehran fault has % 90 potential to movement. In addition the hazard potentials of landslides, settlements, volcanism and dams have been introduced. Finally, geologic hazard map has been prepared and has been divided to10 zones with one to four ranking of risk. -

Iranian Books

IRANIAN BOOKS (Rights Guide) 2018 Children & Picture Books Iranian Book Rights Guide is published by to make available to overseas readers, publishers and literary agencies up-to- date information on Iranian Contemporary authors books and tittles .This issue is dedi- cated to present Iranian awarded and best sellers chil- dren & pictures books. The copy and translation rights of the books described here handled by POL Literary & Translation Agency. POL Literary & Translation Agency Contact Person: Majid Jafari www.pol-ir.ir [email protected] Unit.3, No.108, Inghelab Ave, Nazari Str. Tehran-Iran Tel:+98 21 66480369 Fax:+98 21 66478559 Title: Orange Books(12Vols.) Author: Group of authors Illustrator: Team of illustrators Publisher: Ghadyani Years of Publishing:2014 No. of Pages:192(each Vol) Age Group:8+ Size:"30 × 22 ISBN: 9786002510273 ◙ English text is available. ◙ Copyright sold: Iran(Ghadyani Pubs.),Algeria(Al-Beit Pubs.) About the Book: A sparrow was flying in the sky. Suddenly, one of its feathers was detached and fell to the ground. It touched down to catch its feather and realized it has fallen a, the back of a hedgehog. It asked the hedgehog to return its feather but the hedgehog refused and said that it should not get near and its feather would not be returned. The sparrow was angry. The hedgehog realized that it can make the sparrow comply so they went with the owl who was the judge. The owl asked the sparrow to show the vacant spot from where its feather had detached but the sparrow searched a lot and could not find the spot! The owl said that the sparrow had so many feathers that it could not find the vacant spot of one feather and thus it must have been more generous. -

HIGH COURT of SINDH, KARACHI (Recruitment Test) ADDITIONAL

HIGH COURT OF SINDH, KARACHI (Recruitment Test) Test held on 29 March 2015 ADDITIONAL DISTRICT & SESSIONS JUDGE Sr # Roll No Comp. Code Name Father Name CNIC NTS Marks 1 216 2014900 ATIF UDDIN ASIF UDDIN SIDDIQUI 42201-0790319-5 77 2 381 201369 HAFIZ MISBAHUDDIN NAIMATULLAH PHULPOTO 45504-1133788-1 77 3 64 2013850 ABDUL SHAKOOR KALHORO MUHAMMAD MOOSA KALHORO 45501-1880925-1 75 4 719 201327 MUHAMMAD NAEEM ALLAH WARAYO MEMON 45203-3047320-5 74 5 396 2013467 HATIM AZIZ SOLANGI AZIZ UL HAQ SOLANGI 43203-8847475-5 73 6 390 201371 HALEEM AHMED IMDAD ALI 42301-8902207-5 73 7 74 2013472 ABDULLAH ABDUL WAHAB 42301-0982702-9 72 8 1191 2013494 SYED SAJJAD HUSSAIN SHAH SYED ZAMAN SHAH 45304-1496948-5 72 9 664 2013110 MUHAMMAD ARIF RAJPUT MUHAMMAD RIAZ RAJPUT 44103-1263527-1 72 10 845 20131 NAVEED AHMED SOOMRO AFTAB AHMED SOOMRO 45504-6572854-5 71 11 298 201374 FATIMA JAMEELA JATOI GHULAM QADIR JATOI 45504-1092609-8 71 12 602 2013331 MIAN TAJ MOHAMMAD KEERIO MIAN PEER MOHAMMAD KEERIO 44203-1757881-5 70 13 357 2014929 GHULAM RAZA KHAN MUHAMMAD 42000-4391368-7 70 14 266 2013102 FAHMIDA SAHOOWAL MUHAMMAD HUSSAIN SAHOOWAL 42201-7282118-4 69 15 1214 20141052 TAHIR REHMAN PARVEZ KHAN 42301-7779048-3 69 16 625 2014997 MOHAMMAD NOONARI KALOO NOONARI 41205-0394532-5 69 17 1130 201364 SHYAM LAL ARJAN DAS 45501-1200056-3 69 18 699 2013438 MUHAMMAD ISHAQ KHAN GUL ZAMAN KHAN 42201-6080988-5 69 19 669 20141407 MUHAMMAD ASIF ARAIN MUHAMMAD SHAFI ARAIN 41306-1712567-9 69 20 1243 2013116 UZMA KHAN MUHAMMAD ISHAQ KHAN 42000-8626931-8 69 21 1044 20141194 SEREENA SAEED -

Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran

Negotiating a Position: Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran Parmis Mozafari Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Music January 2011 The candidate confIrms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. 2011 The University of Leeds Parmis Mozafari Acknowledgment I would like to express my gratitude to ORSAS scholarship committee and the University of Leeds Tetly and Lupton funding committee for offering the financial support that enabled me to do this research. I would also like to thank my supervisors Professor Kevin Dawe and Dr Sita Popat for their constructive suggestions and patience. Abstract This research examines the changes in conditions of music and dance after the 1979 revolution in Iran. My focus is the restrictions imposed on women instrumentalists, dancers and singers and the ways that have confronted them. I study the social, religious, and political factors that cause restrictive attitudes towards female performers. I pay particular attention to changes in some specific musical genres and the attitudes of the government officials towards them in pre and post-revolution Iran. I have tried to demonstrate the emotional and professional effects of post-revolution boundaries on female musicians and dancers. Chapter one of this thesis is a historical overview of the position of female performers in pre-modern and contemporary Iran. -

Iran and the Gulf Military Balance - I

IRAN AND THE GULF MILITARY BALANCE - I The Conventional and Asymmetric Dimensions FIFTH WORKING DRAFT By Anthony H. Cordesman and Alexander Wilner Revised July 11, 2012 Anthony H. Cordesman Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy [email protected] Cordesman/Wilner: Iran & The Gulf Military Balance, Rev 5 7/11/12 2 Acknowledgements This analysis was made possible by a grant from the Smith Richardson Foundation. It draws on the work of Dr. Abdullah Toukan and a series of reports on Iran by Adam Seitz, a Senior Research Associate and Instructor, Middle East Studies, Marine Corps University. 2 Cordesman/Wilner: Iran & The Gulf Military Balance, Rev 5 7/11/12 3 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 5 THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................................... 6 Figure III.1: Summary Chronology of US-Iranian Military Competition: 2000-2011 ............................... 8 CURRENT PATTERNS IN THE STRUCTURE OF US AND IRANIAN MILITARY COMPETITION ........................................... 13 DIFFERING NATIONAL PERSPECTIVES .............................................................................................................. 17 US Perceptions .................................................................................................................................... 17 Iranian Perceptions............................................................................................................................ -

Shia-Muslims-Published-By-IMAM.Pdf

Shia Muslims Shia Muslims Our Identity, Our Vision, and the Way Forward Sayyid M. B. Kashmiri Imam Mahdi Association of Marjaeya, Dearborn, MI 48124, www.imam-us.org © 2017, 2018. by Imam Mahdi Association of Marjaeya All rights reserved. Published 2018. Printed in the United States of America ISBN-13: 978-0-9982544-9-4 Second Edition No part of this publication may be reproduced without permission from I.M.A.M., except in cases of fair use. Brief quotations, especially for the purpose of propagating Islamic teachings, are allowed. Contents Preface ............................................................................... vii Our Identity ......................................................................... 1 3 .................................. (التوحيد :Monotheism (Tawhid, Arabic 4 .................................... (المعاد :The Hereafter (Ma’ad, Arabic 7 ....................................................... (العدل :Justice (Adl, Arabic 11 ........................... ( النبوة :Prophethood (Nubuwwah, Arabic 15 ................................. (اﻹمامة :Leadership (Imamate, Arabic Our Vision ......................................................................... 25 Acquiring Moral Attributes ................................................. 27 The Age of Justice ................................................................. 29 The Way Forward .................................................................. 33 Leadership in the Absence of Imam al-Mahdi ........................ 35 Preparation for the Age of the Return -

Download Information from the Internet

IRAN SUBMISSION TO THE HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITTEE FOR THE 103RD SESSION OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITTEE (17 OCTOBER – 4 NOVEMBER 2011) Amnesty International Publications First published in 2011 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org © Amnesty International Publications 2011 Index: MDE 13/081/2011 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. -

Iran Chamber of Commerce,Industries and Mines Date : 2008/01/26 Page: 1

Iran Chamber Of Commerce,Industries And Mines Date : 2008/01/26 Page: 1 Activity type: Exports , State : Tehran Membership Id. No.: 11020060 Surname: LAHOUTI Name: MEHDI Head Office Address: .No. 4, Badamchi Alley, Before Galoubandak, W. 15th Khordad Ave, Tehran, Tehran PostCode: PoBox: 1191755161 Email Address: [email protected] Phone: 55623672 Mobile: Fax: Telex: Membership Id. No.: 11020741 Surname: DASHTI DARIAN Name: MORTEZA Head Office Address: .No. 114, After Sepid Morgh, Vavan Rd., Qom Old Rd, Tehran, Tehran PostCode: PoBox: Email Address: Phone: 0229-2545671 Mobile: Fax: 0229-2546246 Telex: Membership Id. No.: 11021019 Surname: JOURABCHI Name: MAHMOUD Head Office Address: No. 64-65, Saray-e-Park, Kababiha Alley, Bazar, Tehran, Tehran PostCode: PoBox: Email Address: Phone: 5639291 Mobile: Fax: 5611821 Telex: Membership Id. No.: 11021259 Surname: MEHRDADI GARGARI Name: EBRAHIM Head Office Address: 2nd Fl., No. 62 & 63, Rohani Now Sarai, Bazar, Tehran, Tehran PostCode: PoBox: 14611/15768 Email Address: [email protected] Phone: 55633085 Mobile: Fax: Telex: Membership Id. No.: 11022224 Surname: ZARAY Name: JAVAD Head Office Address: .2nd Fl., No. 20 , 21, Park Sarai., Kababiha Alley., Abbas Abad Bazar, Tehran, Tehran PostCode: PoBox: Email Address: Phone: 5602486 Mobile: Fax: Telex: Iran Chamber Of Commerce,Industries And Mines Center (Computer Unit) Iran Chamber Of Commerce,Industries And Mines Date : 2008/01/26 Page: 2 Activity type: Exports , State : Tehran Membership Id. No.: 11023291 Surname: SABBER Name: AHMAD Head Office Address: No. 56 , Beside Saray-e-Khorram, Abbasabad Bazaar, Tehran, Tehran PostCode: PoBox: Email Address: Phone: 5631373 Mobile: Fax: Telex: Membership Id. No.: 11023731 Surname: HOSSEINJANI Name: EBRAHIM Head Office Address: .No. -

Read the Introduction

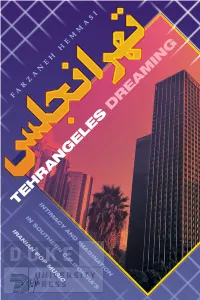

Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING IRANIAN POP MUSIC IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION TEHRANGELES DREAMING Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S IRANIAN POP MUSIC Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Portrait Text Regular and Helvetica Neue Extended by Copperline Book Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Hemmasi, Farzaneh, [date] author. Title: Tehrangeles dreaming : intimacy and imagination in Southern California’s Iranian pop music / Farzaneh Hemmasi. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019041096 (print) lccn 2019041097 (ebook) isbn 9781478007906 (hardcover) isbn 9781478008361 (paperback) isbn 9781478012009 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Music. | Popular music—California—Los Angeles—History and criticism. | Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Ethnic identity. | Iranian diaspora. | Popular music—Iran— History and criticism. | Music—Political aspects—Iran— History—20th century. Classification:lcc ml3477.8.l67 h46 2020 (print) | lcc ml3477.8.l67 (ebook) | ddc 781.63089/915507949—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041096 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041097 Cover art: Downtown skyline, Los Angeles, California, c. 1990. gala Images Archive/Alamy Stock Photo. To my mother and father vi chapter One CONTENTS ix Acknowledgments 1 Introduction 38 1. The Capital of 6/8 67 2. Iranian Popular Music and History: Views from Tehrangeles 98 3. Expatriate Erotics, Homeland Moralities 122 4. Iran as a Singing Woman 153 5. A Nation in Recovery 186 Conclusion: Forty Years 201 Notes 223 References 235 Index ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There is no way to fully acknowledge the contributions of research interlocutors, mentors, colleagues, friends, and family members to this book, but I will try.