Satis N. Coleman File – 01 : Contents, Foreword Pages (I) to (X) Chapters I to IX Pages 1 to 95

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Bell Patterns in West African and Afro-Caribbean Music

Braiding Rhythms: The Role of Bell Patterns in West African and Afro-Caribbean Music A Smithsonian Folkways Lesson Designed by: Jonathan Saxon* Antelope Valley College Summary: These lessons aim to demonstrate polyrhythmic elements found throughout West African and Afro-Caribbean music. Students will listen to music from Ghana, Nigeria, Cuba, and Puerto Rico to learn how this polyrhythmic tradition followed Africans to the Caribbean as a result of the transatlantic slave trade. Students will learn the rumba clave pattern, cascara pattern, and a 6/8 bell pattern. All rhythms will be accompanied by a two-step dance pattern. Suggested Grade Levels: 9–12, college/university courses Countries: Cuba, Puerto Rico, Ghana, Nigeria Regions: West Africa, the Caribbean Culture Groups: Yoruba of Nigeria, Ga of Ghana, Afro-Caribbean Genre: West African, Afro-Caribbean Instruments: Designed for classes with no access to instruments, but sticks, mambo bells, and shakers can be added Language: English Co-Curricular Areas: U.S. history, African-American history, history of Latin American and the Caribbean (also suited for non-music majors) Prerequisites: None. Objectives: Clap and sing clave rhythm Clap and sing cascara rhythm Clap and sing 6/8 bell pattern Dance two-bar phrase stepping on quarter note of each beat in 4/4 time Listen to music from Cuba, Puerto Rico, Ghana, and Nigeria Learn where Cuba, Puerto Rico, Ghana, and Nigeria are located on a map Understand that rhythmic ideas and phrases followed Africans from West Africa to the Caribbean as a result of the transatlantic slave trade * Special thanks to Dr. Marisol Berríos-Miranda and Dr. -

Brass Bands of the World a Historical Directory

Brass Bands of the World a historical directory Kurow Haka Brass Band, New Zealand, 1901 Gavin Holman January 2019 Introduction Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 6 Angola................................................................................................................................ 12 Australia – Australian Capital Territory ......................................................................... 13 Australia – New South Wales .......................................................................................... 14 Australia – Northern Territory ....................................................................................... 42 Australia – Queensland ................................................................................................... 43 Australia – South Australia ............................................................................................. 58 Australia – Tasmania ....................................................................................................... 68 Australia – Victoria .......................................................................................................... 73 Australia – Western Australia ....................................................................................... 101 Australia – other ............................................................................................................. 105 Austria ............................................................................................................................ -

A Replica of the Stretch Clock Recently Reinstated at the West End of Independence Hall

A replica of the Stretch clock recently reinstated at the west end of Independence Hall. (Photograph taken by the author in summer of 197J.) THE Pennsylvania Magazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY The Stretch Qlock and its "Bell at the State House URING the spring of 1973, workmen completed the construc- tion of a replica of a large clock dial and masonry clock D case at the west end of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, the original of which had been installed there in 1753 by a local clockmaker, Thomas Stretch. That equipment, which resembled a giant grandfather's clock, had been removed in about 1830, with no other subsequent effort having been made to reconstruct it. It therefore seems an opportune time to assemble the scattered in- formation regarding the history of that clock and its bell and to present their stories. The acquisition of the original clock and bell by the Pennsylvania colonial Assembly is closely related to the acquisition of the Liberty Bell. Because of this, most historians have tended to focus their writings on that more famous bell, and to pay but little attention to the hard-working, more durable, and equally large clock bell. They have also had a tendency either to claim or imply that the Liberty Bell and the clock bell had been procured in connection with a plan to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary, or "Jubilee Year," of the granting of the Charter of Privileges to the colony by William Penn. But, with one exception, nothing has been found among the surviving records which would support such a contention. -

Learning Neural Audio Embeddings for Grounding Semantics in Auditory Perception

Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 60 (2017) 1003-1030 Submitted 8/17; published 12/17 Learning Neural Audio Embeddings for Grounding Semantics in Auditory Perception Douwe Kiela [email protected] Facebook Artificial Intelligence Research 770 Broadway, New York, NY 10003, USA Stephen Clark [email protected] Computer Laboratory, University of Cambridge 15 JJ Thomson Avenue, Cambridge CB3 0FD, UK Abstract Multi-modal semantics, which aims to ground semantic representations in perception, has relied on feature norms or raw image data for perceptual input. In this paper we examine grounding semantic representations in raw auditory data, using standard evaluations for multi-modal semantics. After having shown the quality of such auditorily grounded repre- sentations, we show how they can be applied to tasks where auditory perception is relevant, including two unsupervised categorization experiments, and provide further analysis. We find that features transfered from deep neural networks outperform bag of audio words approaches. To our knowledge, this is the first work to construct multi-modal models from a combination of textual information and auditory information extracted from deep neural networks, and the first work to evaluate the performance of tri-modal (textual, visual and auditory) semantic models. 1. Introduction Distributional models (Turney & Pantel, 2010; Clark, 2015) have proved useful for a variety of core artificial intelligence tasks that revolve around natural language understanding. The fact that such models represent the meaning of a word as a distribution over other words, however, implies that they suffer from the grounding problem (Harnad, 1990); i.e. they do not account for the fact that human semantic knowledge is grounded in the perceptual system (Louwerse, 2008). -

TD-30 Data List

Data List Preset Drum Kit List No. Name Pad pattern No. Name Pad pattern 1 Studio 41 RockGig 2 LA Metal 42 Hard BeBop 3 Swingin’ 43 Rock Solid 4 Burnin’ 44 2nd Line 5 Birch 45 ROBO TAP 6 Nashville 46 SATURATED 7 LoudRock 47 piccolo 8 JJ’s DnB 48 FAT 9 Djembe 49 BigHall 10 Stage 50 CoolGig LOOP 11 RockMaster 51 JazzSes LOOP 12 LoudJazz 52 7/4 Beat LOOP 13 Overhead 53 :neotype: 1SHOT, TAP 14 Looooose 54 FLA>n<GER 1SHOT, TAP 15 Fusion 55 CustomWood 16 Room 56 50s King 17 [RadioMIX] 57 BluesRock 18 R&B 58 2HH House 19 Brushes 59 TechFusion 20 Vision LOOP, TAP 60 BeBop 21 AstroNote 1SHOT 61 Crossover 22 acidfunk 62 Skanky 23 PunkRock 63 RoundBdge 24 OpenMaple 64 Metal\Core 25 70s Rock 65 JazzCombo 26 DrySound 66 Spark! 27 Flat&Shallow 67 80sMachine 28 Rvs!Trashy 68 =cosmic= 29 melodious TAP 69 1985 30 HARD n’BASS TAP 70 TR-808 31 BazzKicker 71 TR-909 32 FatPressed 72 LatinDrums 33 DrumnDubStep 73 Latin 34 ReMix-ulator 74 Brazil 35 Acoutronic 75 Cajon 36 HipHop 76 African 37 90sHouse 77 Ka-Rimba 38 D-N-B LOOP 78 Tabla TAP 39 SuperLoop TAP 79 Asian 40 >>process>>> 80 Orchestra TAP Copyright © 2012 ROLAND CORPORATION All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of ROLAND CORPORATION. Roland and V-Drums are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Roland Corporation in the United States and/or other countries. -

A Proposed Campanile for Kansas State College

A PROPOSED CAMPANILE FOR KANSAS STATE COLLEGE by NILES FRANKLIN 1.1ESCH B. S., Kansas State College of Agriculture and Applied Science, 1932 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE KANSAS STATE COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND APPLIED SCIENCE 1932 LV e.(2 1932 Rif7 ii. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 THE EARLY HISTORY OF BELLS 3 BELL FOUNDING 4 BELL TUNING 7 THE EARLY HISTORY OF CAMPANILES 16 METHODS OF PLAYING THE CARILLON 19 THE PROPOSED CAMPANILE 25 The Site 25 Designing the Campanile 27 The Proposed Campanile as Submitted By the Author 37 A Model of the Proposed Campanile 44 SUMMARY '47 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 54 LITERATURE CITED 54 1. INTRODUCTION The purpose of this thesis is to review and formulate the history and information concerning bells and campaniles which will aid in the designing of a campanile suitable for Kansas State College. It is hoped that the showing of a design for such a structure with the accompanying model will further stimulate the interest of both students, faculty members, and others in the ultimate completion of such a project. The design for such a tower began about two years ago when the senior Architectural Design Class, of which I was a member, was given a problem of designing a campanile for the campus. The problem was of great interest to me and became more so when I learned that the problem had been given to the class with the thought in mind that some day a campanile would be built. -

FA-06 and FA-08 Sound List

Contents Studio Sets . 3 Preset/User Tones . 4 SuperNATURAL Acoustic Tone . 4 SuperNATURAL Synth Tone . 5 SuperNATURAL Drum Kit . .15 PCM Synth Tone . .15 PCM Drum Kit . .23 GM2 Tone (PCM Synth Tone) . .24 GM2 Drum Kit (PCM Drum Kit) . .26 Drum Kit Key Assign List . .27 Waveforms . .40 Super NATURAL Synth PCM Waveform . .40 PCM Synth Waveform . .42 Copyright © 2014 ROLAND CORPORATION All rights reserved . No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of ROLAND CORPORATION . © 2014 ローランド株式会社 本書の一部、もしくは全部を無断で複写・転載することを禁じます。 2 Studio Sets (Preset) No Studio Set Name MSB LSB PC 56 Dear My Friends 85 64 56 No Studio Set Name MSB LSB PC 57 Nice Brass Sect 85 64 57 1 FA Preview 85 64 1 58 SynStr /SoloLead 85 64 58 2 Jazz Duo 85 64 2 59 DistBs /TranceChd 85 64 59 3 C .Bass/73Tine 85 64 3 60 SN FingBs/Ac .Gtr 85 64 60 4 F .Bass/P .Reed 85 64 4 61 The Begin of A 85 64 61 5 Piano + Strings 85 64 5 62 Emotionally Pad 85 64 62 6 Dynamic Str 85 64 6 63 Seq:Templete 85 64 63 7 Phase Time 85 64 7 64 GM2 Templete 85 64 64 8 Slow Spinner 85 64 8 9 Golden Layer+Pno 85 64 9 10 Try Oct Piano 85 64 10 (User) 11 BIG Stack Lead 85 64 11 12 In Trance 85 64 12 No Studio Set Name MSB LSB PC 13 TB Clone 85 64 13 1–128 INIT STUDIO 85 0 1–128 129– 14 Club Stack 85 64 14 INIT STUDIO 85 1 1–128 256 15 Master Control 85 64 15 257– INIT STUDIO 85 2 1–128 16 XYZ Files 85 64 16 384 17 Fairies 85 64 17 385– INIT STUDIO 85 3 1–128 18 Pacer 85 64 18 512 19 Voyager 85 64 19 * When shipped from the factory, all USER locations were set to INIT STUDIO . -

PERCUSSION INSTRUMENTS of the ORCHESTRA Cabasa

PERCUSSION INSTRUMENTS OF THE ORCHESTRA Cabasa - A rattle consisting of a small gourd covered with a loose network of strung beads. It is held by a handle and shaken with a rotating motion. Claves - A pair of hardwood cylinders, each approximately 20 cm. long. One cylinder rests against the fingernails of a loosely formed fist (cupped to act as a resonator) and is struck with the other cylinder. Cowbell - A metal bell, usually with straight sides and a slightly expanding, nearly rectangular cross section. A type without a clapper and played with a drumstick is most often used in orchestras. Castanets - Consists of two shell-shaped pieces of wood, the hollow sides of which are clapped together. They produce an indefinite pitch and are widely used in Spanish music especially to accompany dance. When used in an orchestra, they are often mounted on either side of a piece of wood that is held by the player and shaken. Sleigh bells - Small pellet bells mounted in rows on a piece of wood with a protruding handle. Tambourine - A shallow, single-headed frame drum with a wooden frame in which metal disks or jingles are set. It is most often held in one hand and struck with the other. Bongos - A permanently attached pair of small, single-headed, cylindrical or conical drums. One drum is of slightly larger diameter and is tuned about a fifth below the smaller. The pair is held between the knees and struck with the hands. Maracas - A Latin American rattle consisting of a round or oval-shaped vessel filled with seeds or similar material and held by a handle. -

Bellfounders.Pdf

| ============================================================== | ============================================================== | | | | | | TERMS OF USE | | | | | CARILLONS OF THE WORLD | The PDF files which constitute the online edition of this | | --------- -- --- ----- | publication are subject to the following terms of use: | | | (1) Only the copy of each file which is resident on the | | | GCNA Website is sharable. That copy is subject to revision | | Privately published on behalf of the | at any time without prior notice to anyone. | | World Carillon Federation and its member societies | (2) A visitor to the GCNA Website may download any of the | | | available PDF files to that individual's personal computer | | by | via a Web browser solely for viewing and optionally for | | | printing at most one copy of each page. | | Carl Scott Zimmerman | (3) A file copy so downloaded may not be further repro- | | Chairman of the former | duced or distributed in any manner, except as incidental to | | Special Committee on Tower and Carillon Statistics, | the course of regularly scheduled backups of the disk on | | The Guild of Carillonneurs in North America | which it temporarily resides. In particular, it may not be | | | subject to file sharing over a network. | | ------------------------------------------------------- | (4) A print copy so made may not be further reproduced. | | | | | Online Edition (a set of Portable Document Format files) | | | | CONTENTS | | Copyright November 2007 by Carl Scott Zimmerman | | | | The main purpose of this publication is to identify and | | All rights reserved. No part of this publication may | describe all of the traditional carillons in the world. But | | be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or trans- | it also covers electrified carillons, chimes, rings, zvons | | mitted, in any form other than its original, or by any | and other instruments or collections of 8 or more tower bells | | means (electronic, photographic, xerographic, recording | (even if not in a tower), and other significant tower bells. -

TC 1-19.30 Percussion Techniques

TC 1-19.30 Percussion Techniques JULY 2018 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release: distribution is unlimited. Headquarters, Department of the Army This publication is available at the Army Publishing Directorate site (https://armypubs.army.mil), and the Central Army Registry site (https://atiam.train.army.mil/catalog/dashboard) *TC 1-19.30 (TC 12-43) Training Circular Headquarters No. 1-19.30 Department of the Army Washington, DC, 25 July 2018 Percussion Techniques Contents Page PREFACE................................................................................................................... vii INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... xi Chapter 1 BASIC PRINCIPLES OF PERCUSSION PLAYING ................................................. 1-1 History ........................................................................................................................ 1-1 Definitions .................................................................................................................. 1-1 Total Percussionist .................................................................................................... 1-1 General Rules for Percussion Performance .............................................................. 1-2 Chapter 2 SNARE DRUM .......................................................................................................... 2-1 Snare Drum: Physical Composition and Construction ............................................. -

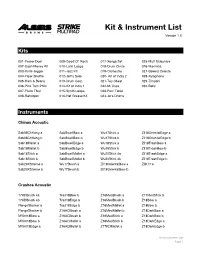

Strike Multipad Kit & Instrument List

Kit & Instrument List Version 1.0 Kits 001-Power Duel 009-Good Ol' Rock 017-Xonga Set 025-Mult Sidesnare 002-Cash Money Kit 010-Latin Loops 018-Drum Circle 026-Marimba 003-Knife Jogger 011-Jazz Kit 019-Orchestra 027-Bowed Celeste 004-Piper Shuffle 012-Jeff's Solo 020- Kit of India 2 028-Xylophone 005-Ham & Beans 013-Drum Corp 021-Toy Chest 029-Timpani 006-Pink Tom Phils 014-Kit of India 1 022-Mi Casa 030-Bells 007-Pluck This! 015-Synth Loops 023-Perc Table 008-Randojon 016-Hat Grease Kit 024-Jo's Drums Instruments Chinas Acoustic Sab08ChKang a SabBwellBow a Wu17Stick a Zil18OrientalEdge a Sab08ChKang b SabBwellBow b Wu17Stick b Zil18OrientalEdge b Sab18Mallet a SabBwellEdge a Wu18Stick a Zil18TrashBow a Sab18Mallet b SabBwellEdge b Wu18Stick b Zil18TrashBow b Sab18Stick a SabBwellMallet a Wu20Stick 4a Zil18TrashEdge a Sab18Stick b SabBwellMallet b Wu20Stick 4b Zil18TrashEdge b Sab20XStreme a Wu17Brush a Zil18OrientalBow a ZilK17 a Sab20XStreme b Wu17Brush b Zil18OrientalBow b Crashes Acoustic 17KDBrush 4a Trad18Bow b Z16MedBrush a Z17MedStick b 17KDBrush 4b Trad18Edge a Z16MedBrush b Z18Bow a FlangeStacker a Trad18Edge b Z16MedMallet a Z18Bow b FlangeStacker b Z16ACBrush a Z16MedMallet b Z18DarkBow a MVint18Bow a Z16ACBrush b Z16MedStick a Z18DarkBow b MVint18Bow b Z16ACMallet a Z16MedStick b Z18DarkEdge a MVint18Edge a Z16ACMallet b Z17KDMallet a Z18DarkEdge b Kit & Instrument List Page 1 Crashes Acoustic (continued) PSSab Stacker a Z16ACStick b Z17KDStick a Z18Edge b PSSab Stacker b Z16DarkBrush a Z17KDStick b Z18MedBrush a Smashed17in -

Afro-Brazilian Songs and Rhythms for General Music K-8

Dr. Christopher H. Fashun Assistant Professor of Music, Hope College ([email protected]) Afro-Brazilian Songs and Rhythms for General Music K-8 Candomblé: The Afro-Brazilian Religion of Bahia Candomblé is the Afro-Brazilian religion of Brazil that originated in the state of Bahia in northeast Brazil. It is part of the religion and culture of the Africa diaspora, which include the religions of Cuban Santeria and Vodun of Haiti. Although the spellings and pronunciations of the deities (called orixás in Candomblé) are different between the countries due to syncretism and miscegenation, they have a shared tradition of rituals, songs, rhythms, mythology, worship, and social and cultural context. Of the approximate 10 million Africans that were enslaved and brought to the Americas, 4 million of those landed in Brazil. During the years of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade (1500-1850), Africans were taken from 3 different regions. Candomblé originated in the state of Bahia and its capital city of Salvador as a result of the concentration of enslaved Africans. The religious traditions of the enslaved Africans were founded on practices from Central and West Africa, who believed in a single god that was accompanied by a pantheon of deities called Orixás. Due to the mixing of the different tribal and cultural groups, the slaves were allowed to form irmandades, which were social organizations of Catholic lay brotherhoods that allowed the slaves to gather together from their points of origin in Africa. As a result of oppression, the enslaved Africans disguised their worship by syncretizing the orixás and religious rituals with the saints of Catholicism.