The Function of NM23-H1/NME1 and Its Homologs in Major Processes Linked to Metastasis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gene Symbol Gene Description ACVR1B Activin a Receptor, Type IB

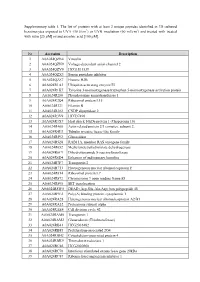

Table S1. Kinase clones included in human kinase cDNA library for yeast two-hybrid screening Gene Symbol Gene Description ACVR1B activin A receptor, type IB ADCK2 aarF domain containing kinase 2 ADCK4 aarF domain containing kinase 4 AGK multiple substrate lipid kinase;MULK AK1 adenylate kinase 1 AK3 adenylate kinase 3 like 1 AK3L1 adenylate kinase 3 ALDH18A1 aldehyde dehydrogenase 18 family, member A1;ALDH18A1 ALK anaplastic lymphoma kinase (Ki-1) ALPK1 alpha-kinase 1 ALPK2 alpha-kinase 2 AMHR2 anti-Mullerian hormone receptor, type II ARAF v-raf murine sarcoma 3611 viral oncogene homolog 1 ARSG arylsulfatase G;ARSG AURKB aurora kinase B AURKC aurora kinase C BCKDK branched chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase BMPR1A bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type IA BMPR2 bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type II (serine/threonine kinase) BRAF v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 BRD3 bromodomain containing 3 BRD4 bromodomain containing 4 BTK Bruton agammaglobulinemia tyrosine kinase BUB1 BUB1 budding uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 homolog (yeast) BUB1B BUB1 budding uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 homolog beta (yeast) C9orf98 chromosome 9 open reading frame 98;C9orf98 CABC1 chaperone, ABC1 activity of bc1 complex like (S. pombe) CALM1 calmodulin 1 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CALM2 calmodulin 2 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CALM3 calmodulin 3 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CAMK1 calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase I CAMK2A calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaM kinase) II alpha CAMK2B calcium/calmodulin-dependent -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Protein Identities in Evs Isolated from U87-MG GBM Cells As Determined by NG LC-MS/MS

Protein identities in EVs isolated from U87-MG GBM cells as determined by NG LC-MS/MS. No. Accession Description Σ Coverage Σ# Proteins Σ# Unique Peptides Σ# Peptides Σ# PSMs # AAs MW [kDa] calc. pI 1 A8MS94 Putative golgin subfamily A member 2-like protein 5 OS=Homo sapiens PE=5 SV=2 - [GG2L5_HUMAN] 100 1 1 7 88 110 12,03704523 5,681152344 2 P60660 Myosin light polypeptide 6 OS=Homo sapiens GN=MYL6 PE=1 SV=2 - [MYL6_HUMAN] 100 3 5 17 173 151 16,91913397 4,652832031 3 Q6ZYL4 General transcription factor IIH subunit 5 OS=Homo sapiens GN=GTF2H5 PE=1 SV=1 - [TF2H5_HUMAN] 98,59 1 1 4 13 71 8,048185945 4,652832031 4 P60709 Actin, cytoplasmic 1 OS=Homo sapiens GN=ACTB PE=1 SV=1 - [ACTB_HUMAN] 97,6 5 5 35 917 375 41,70973209 5,478027344 5 P13489 Ribonuclease inhibitor OS=Homo sapiens GN=RNH1 PE=1 SV=2 - [RINI_HUMAN] 96,75 1 12 37 173 461 49,94108966 4,817871094 6 P09382 Galectin-1 OS=Homo sapiens GN=LGALS1 PE=1 SV=2 - [LEG1_HUMAN] 96,3 1 7 14 283 135 14,70620005 5,503417969 7 P60174 Triosephosphate isomerase OS=Homo sapiens GN=TPI1 PE=1 SV=3 - [TPIS_HUMAN] 95,1 3 16 25 375 286 30,77169764 5,922363281 8 P04406 Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase OS=Homo sapiens GN=GAPDH PE=1 SV=3 - [G3P_HUMAN] 94,63 2 13 31 509 335 36,03039959 8,455566406 9 Q15185 Prostaglandin E synthase 3 OS=Homo sapiens GN=PTGES3 PE=1 SV=1 - [TEBP_HUMAN] 93,13 1 5 12 74 160 18,68541938 4,538574219 10 P09417 Dihydropteridine reductase OS=Homo sapiens GN=QDPR PE=1 SV=2 - [DHPR_HUMAN] 93,03 1 1 17 69 244 25,77302971 7,371582031 11 P01911 HLA class II histocompatibility antigen, -

Characterization of the Small Molecule Kinase Inhibitor SU11248 (Sunitinib/ SUTENT in Vitro and in Vivo

TECHNISCHE UNIVERSITÄT MÜNCHEN Lehrstuhl für Genetik Characterization of the Small Molecule Kinase Inhibitor SU11248 (Sunitinib/ SUTENT in vitro and in vivo - Towards Response Prediction in Cancer Therapy with Kinase Inhibitors Michaela Bairlein Vollständiger Abdruck der von der Fakultät Wissenschaftszentrum Weihenstephan für Ernährung, Landnutzung und Umwelt der Technischen Universität München zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften genehmigten Dissertation. Vorsitzender: Univ. -Prof. Dr. K. Schneitz Prüfer der Dissertation: 1. Univ.-Prof. Dr. A. Gierl 2. Hon.-Prof. Dr. h.c. A. Ullrich (Eberhard-Karls-Universität Tübingen) 3. Univ.-Prof. A. Schnieke, Ph.D. Die Dissertation wurde am 07.01.2010 bei der Technischen Universität München eingereicht und durch die Fakultät Wissenschaftszentrum Weihenstephan für Ernährung, Landnutzung und Umwelt am 19.04.2010 angenommen. FOR MY PARENTS 1 Contents 2 Summary ................................................................................................................................................................... 5 3 Zusammenfassung .................................................................................................................................................... 6 4 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................. 8 4.1 Cancer .............................................................................................................................................................. -

Development and Validation of a Protein-Based Risk Score for Cardiovascular Outcomes Among Patients with Stable Coronary Heart Disease

Supplementary Online Content Ganz P, Heidecker B, Hveem K, et al. Development and validation of a protein-based risk score for cardiovascular outcomes among patients with stable coronary heart disease. JAMA. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5951 eTable 1. List of 1130 Proteins Measured by Somalogic’s Modified Aptamer-Based Proteomic Assay eTable 2. Coefficients for Weibull Recalibration Model Applied to 9-Protein Model eFigure 1. Median Protein Levels in Derivation and Validation Cohort eTable 3. Coefficients for the Recalibration Model Applied to Refit Framingham eFigure 2. Calibration Plots for the Refit Framingham Model eTable 4. List of 200 Proteins Associated With the Risk of MI, Stroke, Heart Failure, and Death eFigure 3. Hazard Ratios of Lasso Selected Proteins for Primary End Point of MI, Stroke, Heart Failure, and Death eFigure 4. 9-Protein Prognostic Model Hazard Ratios Adjusted for Framingham Variables eFigure 5. 9-Protein Risk Scores by Event Type This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/02/2021 Supplemental Material Table of Contents 1 Study Design and Data Processing ......................................................................................................... 3 2 Table of 1130 Proteins Measured .......................................................................................................... 4 3 Variable Selection and Statistical Modeling ........................................................................................ -

Association of Genetic Polymorphisms in Genes Involved in Ara-C And

Zhu et al. J Transl Med (2018) 16:90 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-018-1463-1 Journal of Translational Medicine RESEARCH Open Access Association of genetic polymorphisms in genes involved in Ara‑C and dNTP metabolism pathway with chemosensitivity and prognosis of adult acute myeloid leukemia (AML) Ke‑Wei Zhu1,2, Peng Chen1,2, Dao‑Yu Zhang1,2, Han Yan1,2, Han Liu1,2, Li‑Na Cen1,2, Yan‑Ling Liu1,2, Shan Cao1,2, Gan Zhou1,2, Hui Zeng4, Shu‑Ping Chen4, Xie‑Lan Zhao4 and Xiao‑Ping Chen1,2,3,5* Abstract Background: Cytarabine arabinoside (Ara-C) has been the core of chemotherapy for adult acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Ara-C undergoes a three-step phosphorylation into the active metabolite Ara-C triphosphosphate (ara-CTP). Several enzymes are involved directly or indirectly in either the formation or detoxifcation of ara-CTP. Methods: A total of 12 eQTL (expression Quantitative Trait Loci) single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) or tag SNPs in 7 genes including CMPK1, NME1, NME2, RRM1, RRM2, SAMHD1 and E2F1 were genotyped in 361 Chinese non-M3 AML patients by using the Sequenom Massarray system. Association of the SNPs with complete remission (CR) rate after Ara-C based induction therapy, relapse-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) were analyzed. Results: Three SNPs were observed to be associated increased risk of chemoresistance indicated by CR rate (NME2 rs3744660, E2F1 rs3213150, and RRM2 rs1130609), among which two (rs3744660 and rs1130609) were eQTL. Com‑ bined genotypes based on E2F1 rs3213150 and RRM2 rs1130609 polymorphisms further increased the risk of non-CR. -

Assessing the Human Canonical Protein Count[Version 1; Peer Review

F1000Research 2017, 6:448 Last updated: 15 JUL 2020 REVIEW Last rolls of the yoyo: Assessing the human canonical protein count [version 1; peer review: 1 approved, 2 approved with reservations] Christopher Southan IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology, Centre for Integrative Physiology, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, EH8 9XD, UK First published: 07 Apr 2017, 6:448 Open Peer Review v1 https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.11119.1 Latest published: 07 Apr 2017, 6:448 https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.11119.1 Reviewer Status Abstract Invited Reviewers In 2004, when the protein estimate from the finished human genome was 1 2 3 only 24,000, the surprise was compounded as reviewed estimates fell to 19,000 by 2014. However, variability in the total canonical protein counts version 1 (i.e. excluding alternative splice forms) of open reading frames (ORFs) in 07 Apr 2017 report report report different annotation portals persists. This work assesses these differences and possible causes. A 16-year analysis of Ensembl and UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot shows convergence to a protein number of ~20,000. The former had shown some yo-yoing, but both have now plateaued. Nine 1 Michael Tress, Spanish National Cancer major annotation portals, reviewed at the beginning of 2017, gave a spread Research Centre (CNIO), Madrid, Spain of counts from 21,819 down to 18,891. The 4-way cross-reference concordance (within UniProt) between Ensembl, Swiss-Prot, Entrez Gene 2 Elspeth A. Bruford , European Molecular and the Human Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC) drops to 18,690, Biology Laboratory, Hinxton, UK indicating methodological differences in protein definitions and experimental existence support between sources. -

Supplementary Table 1. the List of Proteins with at Least 2 Unique

Supplementary table 1. The list of proteins with at least 2 unique peptides identified in 3D cultured keratinocytes exposed to UVA (30 J/cm2) or UVB irradiation (60 mJ/cm2) and treated with treated with rutin [25 µM] or/and ascorbic acid [100 µM]. Nr Accession Description 1 A0A024QZN4 Vinculin 2 A0A024QZN9 Voltage-dependent anion channel 2 3 A0A024QZV0 HCG1811539 4 A0A024QZX3 Serpin peptidase inhibitor 5 A0A024QZZ7 Histone H2B 6 A0A024R1A3 Ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1 7 A0A024R1K7 Tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein 8 A0A024R280 Phosphoserine aminotransferase 1 9 A0A024R2Q4 Ribosomal protein L15 10 A0A024R321 Filamin B 11 A0A024R382 CNDP dipeptidase 2 12 A0A024R3V9 HCG37498 13 A0A024R3X7 Heat shock 10kDa protein 1 (Chaperonin 10) 14 A0A024R408 Actin related protein 2/3 complex, subunit 2, 15 A0A024R4U3 Tubulin tyrosine ligase-like family 16 A0A024R592 Glucosidase 17 A0A024R5Z8 RAB11A, member RAS oncogene family 18 A0A024R652 Methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 19 A0A024R6C9 Dihydrolipoamide S-succinyltransferase 20 A0A024R6D4 Enhancer of rudimentary homolog 21 A0A024R7F7 Transportin 2 22 A0A024R7T3 Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein F 23 A0A024R814 Ribosomal protein L7 24 A0A024R872 Chromosome 9 open reading frame 88 25 A0A024R895 SET translocation 26 A0A024R8W0 DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 48 27 A0A024R9E2 Poly(A) binding protein, cytoplasmic 1 28 A0A024RA28 Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2/B1 29 A0A024RA52 Proteasome subunit alpha 30 A0A024RAE4 Cell division cycle 42 31 -

Adenovirus Strategies for Altering the Cellular Environment in Favor of Infection

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Adenovirus Strategies For Altering The Cellular Environment In Favor Of Infection Christin Herrmann University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Allergy and Immunology Commons, Immunology and Infectious Disease Commons, Medical Immunology Commons, and the Virology Commons Recommended Citation Herrmann, Christin, "Adenovirus Strategies For Altering The Cellular Environment In Favor Of Infection" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3568. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3568 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3568 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Adenovirus Strategies For Altering The Cellular Environment In Favor Of Infection Abstract Viruses, as obligate intracellular pathogens, rely on their host cell for successful replication. Viruses have evolved different strategies to hijack and redirect cellular processes to benefit infection and overcome host immune responses. Understanding the mechanisms by which viruses exploit their host cells will reveal new targets for antiviral therapies. In addition, these studies can provide insights into the regulation of fundamental cellular processes. While much progress has been made in this area, many unexpected nuances of virus-host interaction are still being discovered. Here, we employed several strategies to uncover new aspects of viral manipulation of the host environment by adenovirus, a nuclear-replicating DNA virus that commonly infects humans. The first project focused on how viral histone-like proteins impact cellular chromatin. Adenovirus encodes the small, basic protein VII that coats and condenses viral genomes. The effect of this viral DNA-binding protein on host chromatin structure and function had remained unexplored. -

S41467-020-17157-W.Pdf

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17157-w OPEN Transcriptional activity and strain-specific history of mouse pseudogenes Cristina Sisu 1,2,3,15, Paul Muir4,5,15, Adam Frankish6, Ian Fiddes7, Mark Diekhans 7, David Thybert6,8, Duncan T. Odom 9,10, Paul Flicek 6,10, Thomas M. Keane 6, Tim Hubbard 11, Jennifer Harrow12 & ✉ Mark Gerstein 1,2,5,13,14 Pseudogenes are ideal markers of genome remodelling. In turn, the mouse is an ideal plat- 1234567890():,; form for studying them, particularly with the recent availability of strain-sequencing and transcriptional data. Here, combining both manual curation and automatic pipelines, we present a genome-wide annotation of the pseudogenes in the mouse reference genome and 18 inbred mouse strains (available via the mouse.pseudogene.org resource). We also annotate 165 unitary pseudogenes in mouse, and 303, in human. The overall pseudogene repertoire in mouse is similar to that in human in terms of size, biotype distribution, and family composition (e.g. with GAPDH and ribosomal proteins being the largest families). Notable differences arise in the pseudogene age distribution, with multiple retro- transpositional bursts in mouse evolutionary history and only one in human. Furthermore, in each strain about a fifth of all pseudogenes are unique, reflecting strain-specific evolution. Finally, we find that ~15% of the mouse pseudogenes are transcribed, and that highly tran- scribed parent genes tend to give rise to many processed pseudogenes. 1 Program in Computational Biology and Bioinformatics, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520, USA. 2 Department of Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520, USA. -

Transcriptomic Analysis of Early Stages of Intestinal Regeneration in Holothuria Glaberrima David J

Transcriptomic Analysis of Early Stages of Intestinal Regeneration in Holothuria glaberrima David J. Quispe-Parra1, Joshua G. Medina-Feliciano1, Sebastián Cruz-González1, Humberto Ortiz-Zuazaga2, José E. García-Arrarás1* 1University of Puerto Rico, Biology Department, San Juan, 00925, Puerto Rico. 2University of Puerto Rico, Department of Computer Sciences, San Juan, 00925, Puerto Rico. Table S1. Results of transcriptome assessment with BUSCO Parameter BUSCO result Core genes queried 978 Complete core genes detected 99.1% Complete single copy core genes 27.2% Complete duplicated core genes 71.9% Fragmented core genes detected 0.4% Missing core genes 0.5% Table S2. Transcriptome length statistics and composition assessments with gVolante Parameter Result Number of sequences 491 436 Total length (nt) 408 930 895 Longest sequence (nt) 34 610 Shortest sequence (nt) 200 Mean sequence length (nt) 832 N50 sequence length (nt) 1 691 Table S3. RNA-seq data read statistic values Accession Quantity of reads Sample Mapped reads (SRA) Before Filtering After Filtering SRR12564573 NormalA 89 424 588.00 88 112 720.00 94.18% SRR12564572 NormalB 74 105 862.00 72 983 434.00 93.79% SRR12564570 NormalC 60 626 094.00 59 767 896.00 91.55% SRR12564564 Day1A 32 499 910.00 31 721 976.00 90.67% SRR12564563 Day1B 35 164 514.00 34 237 960.00 91.37% SRR12564571 Day1C 43 519 280.00 42 179 220.00 91.53% SRR12564567 Day3A 64 094 536.00 62 995 792.00 90.26% SRR12564566 Day3B 71 654 462.00 70 158 078.00 91.07% SRR12564565 Day3C 71 259 560.00 70 418 332.00 90.75% SRR12564569 Day3D* 107 688 184.00 106 083 898.00 - SRR12564568 Day3E* 108 372 334.00 106 767 522.00 - *Samples used for the assembly but not for differential expression analysis Table S4. -

A Chromosome-Centric Human Proteome Project (C-HPP) To

computational proteomics Laboratory for Computational Proteomics www.FenyoLab.org E-mail: [email protected] Facebook: NYUMC Computational Proteomics Laboratory Twitter: @CompProteomics Perspective pubs.acs.org/jpr A Chromosome-centric Human Proteome Project (C-HPP) to Characterize the Sets of Proteins Encoded in Chromosome 17 † ‡ § ∥ ‡ ⊥ Suli Liu, Hogune Im, Amos Bairoch, Massimo Cristofanilli, Rui Chen, Eric W. Deutsch, # ¶ △ ● § † Stephen Dalton, David Fenyo, Susan Fanayan,$ Chris Gates, , Pascale Gaudet, Marina Hincapie, ○ ■ △ ⬡ ‡ ⊥ ⬢ Samir Hanash, Hoguen Kim, Seul-Ki Jeong, Emma Lundberg, George Mias, Rajasree Menon, , ∥ □ △ # ⬡ ▲ † Zhaomei Mu, Edouard Nice, Young-Ki Paik, , Mathias Uhlen, Lance Wells, Shiaw-Lin Wu, † † † ‡ ⊥ ⬢ ⬡ Fangfei Yan, Fan Zhang, Yue Zhang, Michael Snyder, Gilbert S. Omenn, , Ronald C. Beavis, † # and William S. Hancock*, ,$, † Barnett Institute and Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Northeastern University, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, United States ‡ Stanford University, Palo Alto, California, United States § Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics (SIB) and University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland ∥ Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States ⊥ Institute for System Biology, Seattle, Washington, United States ¶ School of Medicine, New York University, New York, United States $Department of Chemistry and Biomolecular Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW, Australia ○ MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas, United States ■ Yonsei University College of Medicine, Yonsei University,