Project Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abbreviations

ABBREVIATIONS ACP African Caribbean Pacific K kindergarten Adm. Admiral kg kilogramme(s) Adv. Advocate kl kilolitre(s) a.i. ad interim km kilometre(s) kW kilowatt b. born kWh kilowatt hours bbls. barrels bd board lat. latitude bn. billion (one thousand million) lb pound(s) (weight) Brig. Brigadier Lieut. Lieutenant bu. bushel long. longitude Cdr Commander m. million CFA Communauté Financière Africaine Maj. Major CFP Comptoirs Français du Pacifique MW megawatt CGT compensated gross tonnes MWh megawatt hours c.i.f. cost, insurance, freight C.-in-C. Commander-in-Chief NA not available CIS Commonwealth of Independent States n.e.c. not elsewhere classified cm centimetre(s) NRT net registered tonnes Col. Colonel NTSC National Television System Committee cu. cubic (525 lines 60 fields) CUP Cambridge University Press cwt hundredweight OUP Oxford University Press oz ounce(s) D. Democratic Party DWT dead weight tonnes PAL Phased Alternate Line (625 lines 50 fields 4·43 MHz sub-carrier) ECOWAS Economic Community of West African States PAL M Phased Alternate Line (525 lines 60 PAL EEA European Economic Area 3·58 MHz sub-carrier) EEZ Exclusive Economic Zone PAL N Phased Alternate Line (625 lines 50 PAL EMS European Monetary System 3·58 MHz sub-carrier) EMU European Monetary Union PAYE Pay-As-You-Earn ERM Exchange Rate Mechanism PPP Purchasing Power Parity est. estimate f.o.b. free on board R. Republican Party FDI foreign direct investment retd retired ft foot/feet Rt Hon. Right Honourable FTE full-time equivalent SADC Southern African Development Community G8 Group Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, UK, SDR Special Drawing Rights USA, Russia SECAM H Sequential Couleur avec Mémoire (625 lines GDP gross domestic product 50 fieldsHorizontal) Gen. -

Militarized Youths in Western Côte D'ivoire

Militarized youths in Western Côte d’Ivoire - Local processes of mobilization, demobilization, and related humanitarian interventions (2002-2007) Magali Chelpi-den Hamer To cite this version: Magali Chelpi-den Hamer. Militarized youths in Western Côte d’Ivoire - Local processes of mobiliza- tion, demobilization, and related humanitarian interventions (2002-2007). African Studies Centre, 36, 2011, African Studies Collection. hal-01649241 HAL Id: hal-01649241 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01649241 Submitted on 27 Nov 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. African Studies Centre African Studies Collection, Vol. 36 Militarized youths in Western Côte d’Ivoire Local processes of mobilization, demobilization, and related humanitarian interventions (2002-2007) Magali Chelpi-den Hamer Published by: African Studies Centre P.O. Box 9555 2300 RB Leiden The Netherlands [email protected] www.ascleiden.nl Cover design: Heike Slingerland Cover photo: ‘Market scene, Man’ (December 2007) Photographs: Magali Chelpi-den Hamer Printed by Ipskamp -

FERDI-WP266-Civil Conflict and Firm Recovery: Evidence from Post

Pap ing er rk o W s fondation pour les études et recherches sur le développement international e D i 266May c e li ve 2020 o lopment P Civil conflict and firm recovery: Evidence from post-electoral crisis in Côte d’Ivoire* Florian Léon Ibrahima Dosso Florian Léon, Research Officer, FERDI. [email protected] Ibrahima Dosso, Consultant, World Bank, PhD Student, Université Clermont Auvergne, CERDI. [email protected] Abstract This paper examines how firms recover after a short, but severe, external shock. Thanks to a rich firm-level database, we follow surviving formal enterprises before, during and after the 2011 post-electoral crisis in Cˆote d’Ivoire. Main findings are summarized as follows. First, recovery was rapid in the first year but imperfect: three years after the shock, firms did not reach their previous level of productivity. Second, we show a wide heterogeneity in recovery across firms (within the same industry). Young and local firms were more able to rebound after the crisis. In addition, credit-constrained firms were less resilient, highlighting the importance of access to credit in post-crisis periods. Finally, the recovery was higher for labor- intensive firms but firms relying more on skilled workers and managers faced a lower rebound. Key words: Political violence; Firm; Recovery; Africa; Labor. JEL Classification: D22; L25; N47; O12. * We would like to thank the National Institute of Statistics for sharing data with us. We also thank Pierrick Baraton, Luisito Bertinelli, Arnaud Bourgain, Joël Cariolle, Lisa Chauvet, Boubacar Diallo, Marie-Hélène Hubert, Jordan Loper, Patrick Plane, Laurent Weill and Alexandra Zins, as well as participants at African Development Bank (Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire) and CERDI (Clermont-Ferrand, France), and audiences at JMA (Casablanca, Morocco) and AFSE Conference (Orléans, France), for their helpful advice. -

REGION DE L'iffou Public 321 1 718 1 758 58 965 28 174 6 437 3 358 1 705 584 Total 336 1 773 1 809 61 094 29 207 6 599 3 439 1 751 592

REPUBLIQUE DE CÔTE D’IVOIRE Union- Discipline-Travail MINISTERE DE L’EDUCATION NATIONALE, DE L’ENSEIGNEMENT TECHNIQUE ET DE LA FORMATION PROFESSIONNELLE ANNUAIRE STATISTIQUE SCOLAIRE 2017 - 2018 REGION DE L’IFFOU MENET-FP/DSPS/DRENET DAOUKRO/ANNUAIRE STATISTIQUE SCOLAIRE 2017-2018 : REGION DE L’IFFOU 1 SOMMAIRE Contenu Sommaire ..................................................................................................................................................................2 A. PRESCOLAIRE ........................................................................................................................................................5 A-1. DONNEES SYNTHETIQUES .............................................................................................................................6 Tableau 1 : Répartition des infrastructures, des effectifs élèves et des enseignants par département, par sous-préfecture et par statut ...........................................................................................................................7 Graphique A-1: Proportion des écoles selon le statut de l’école dans le préscolaire ......................................8 Graphique A-2. Proportion des élèves selon le statut de l’école dans le préscolaire ......................................8 Graphique A-3. Proportion des élèves selon le genre dans le préscolaire .......................................................8 A-2. INDICATEURS GLOBAUX ................................................................................................................................9 -

Use of the Inverse Slope Method for the Characterization of Geometry of Basement Aquifers: Case of the Department of Bouna (Ivory Coast)

Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection, 2019, 7, 166-183 http://www.scirp.org/journal/gep ISSN Online: 2327-4344 ISSN Print: 2327-4336 Use of the Inverse Slope Method for the Characterization of Geometry of Basement Aquifers: Case of the Department of Bouna (Ivory Coast) Rock Armand Michel Bouadou1, Kouamé Auguste Kouassi1, Francis Williams Kouassi1, Adama Coulibaly2, Théophile Gnagne1 1Laboratory of Geosciences and Environment, UFR of Sciences and Management of the Environment, University of Nangui Abrogoua, Abidjan, Ivory Coast 2Department of Science and Technology of Water and Environmental Engineering, UFR of Earth Sciences and Mineral Resources, University of Félix Houphouët-Boigny, Abidjan, Ivory Coast How to cite this paper: Bouadou, R. A. M., Abstract Kouassi, K. A., Kouassi, F. W., Coulibaly, A., & Gnagne, T. (2019). Use of the Inverse The inverse slope method (ISM) was used to interpret electric sounding data Slope Method for the Characterization of to determine the geoelectric parameters of the alteration zones (continuous Geometry of Basement Aquifers: Case of media) and rocky environments (discontinuous environments) of the Bouna the Department of Bouna (Ivory Coast). Journal of Geoscience and Environment Department. Having both qualitative and quantitative interpretation, the in- Protection, 7, 166-183. verse slope method (ISM) has the ability to determine the different geoelectric https://doi.org/10.4236/gep.2019.76014 layers while characterizing their resistivities and true thicknesses. In the Bouna department, this method allowed us to count a maximum of four (4) Received: April 24, 2019 Accepted: June 27, 2019 geoelectric layers with a total thickness ranging from 12.99 m to 24.66 m. -

Monthly Humanitarian Report November 2011

Côte d’Ivoire Rapport Humanitaire Mensuel Novembre 2011 Côte d’Ivoire Monthly Humanitarian Report November 2011 www.unocha.org The mission of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) is to mobilize and coordinate effective and principled humanitarian action in partnership with national and international actors. Coordination Saves Lives • Celebrating 20 years of coordinated humanitarian action November 2011 Côte d’Ivoire Monthly Bulletin | 2 Côte d’Ivoire Monthly Humanitarian Report Coordination Saves Lives Coordination Saves Lives No. 2 | November 2011 HIGHLIGHTS Voluntary and spontaneous repatriation of Ivorian refugees from Liberia continues in Western Cote d’Ivoire. African Union (AU) delegation visited Duékoué, West of Côte d'Ivoire. Tripartite agreement signed in Lomé between Ivorian and Togolese Governments and the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). Voluntary return of internally displaced people from the Duekoue Catholic Church to their areas of origin. World Food Program (WFP) published the findings of the post-distribution survey carried out from 14 to 21 October among 240 beneficiaries in 20 villages along the Liberian border (Toulépleu, Zouan- Hounien and Bin-Houyé). Child Protection Cluster in collaboration with Save the Children and UNICEF published The Vulnerabilities, Violence and Serious violations of Child Rights report. The Special Representative of the UN Secretary General on Sexual Violence in Conflict, Mrs. Margot Wallström on a six day visit to Côte d'Ivoire. I. GENERAL CONTEXT No major incident has been reported in November except for the clashes that broke out on 1 November between ethnic Guéré people and a group of dozos (traditional hunters). -

Côte D'ivoire Country Focus

European Asylum Support Office Côte d’Ivoire Country Focus Country of Origin Information Report June 2019 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Côte d’Ivoire Country Focus Country of Origin Information Report June 2019 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9476-993-0 doi: 10.2847/055205 © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2019 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Mariam Dembélé, Abidjan (December 2016) CÔTE D’IVOIRE: COUNTRY FOCUS - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT — 3 Acknowledgements EASO acknowledges as the co-drafters of this report: Italy, Ministry of the Interior, National Commission for the Right of Asylum, International and EU Affairs, COI unit Switzerland, State Secretariat for Migration (SEM), Division Analysis The following departments reviewed this report, together with EASO: France, Office Français de Protection des Réfugiés et Apatrides (OFPRA), Division de l'Information, de la Documentation et des Recherches (DIDR) Norway, Landinfo The Netherlands, Immigration and Naturalisation Service, Office for Country of Origin Information and Language Analysis (OCILA) Dr Marie Miran-Guyon, Lecturer at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), researcher, and author of numerous publications on the country reviewed this report. It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. -

Assessment of the Implementation of Alternative Process Technologies for Rural Heat and Power Production from Cocoa Pod Husks

Assessment of the implementation of alternative process technologies for rural heat and power production from cocoa pod husks Dimitra Maleka Master of Science Thesis KTH School of Industrial Engineering and Management Department of Energy Technology Division of Heat and Power Technology SE-100 44 STOCKHOLM Master of Science Thesis EGI 2016: 034 MSC EKV1137 Assessment of the implementation of alternative process technologies for rural heat and power production from cocoa pod husks Dimitra Maleka Approved Examiner Supervisors Reza Fakhraie Reza Fakhraie (KTH) David Bauner (Renetech AB) Commissioner Contact person ii Abstract Cocoa pod husks are generated in Côte d’Ivoire, in abundant quantities annually. The majority is left as waste to decompose at the plantations. A review of the ultimate and proximate composition of CPH resulted in the conclusion that, CPH is a high potential feedstock for both thermochemical and biochemical processes. The main focus of the study was the utilization of CPH in 10,000 tons/year power plants for generation of energy and value-added by-products. For this purpose, the feasibility of five energy conversion processes (direct combustion, gasification, pyrolysis, anaerobic digestion and hydrothermal carbonization) with CPH as feedstock, were investigated. Several indicators were used for the review and comparison of the technologies. Anaerobic digestion and hydrothermal carbonization were found to be the most suitable conversion processes. For both technologies an analysis was conducted including technical, economic, environmental and social aspects. Based on the characterization of CPH, appropriate reactors and operating conditions were chosen for the two processes. Moreover, the plants were chosen to be coupled with CHP units, for heat and power generation. -

Plan Cadre De Gestion Environnementale Et Sociale (PCGES) Du Projet Electrification De 1088 Localités De La Côte D’Ivoire 3 5.6.2

REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D’IVOIRE Union – Discipline – Travail ---------------- MINISTERE DU PETROLE, DE L’ENERGIE REPUBLIQUE DE COTE ET DES ENERGIES RENOUVELABLES GROUPE DE LA BAD D'IVOIRE ---------------- UNION-DISCIPLINE-TRAVAIL ------------ PROJET D’ELECTRIFICATION RURALE DE 1 088 LOCALITES EN COTE D’IVOIRE ------------- Plan Cadre de Gestion Environnementale et Sociale (PCGES) LOT 4 : SASSANDRA-MARAHOUE (31), YAMOUSSOUKRO (01), LACS (93), ZANZAN (88), COMOE (09), LAGUNES (09) RAPPORT FINAL Octobre 2019 Abidjan Riviera palmeraie Triangle Résidence Mariam appt. B4 - 20 BP 12 ABJ 20 Tel : 07 21 17 83 – 01 14 01 40 Email : [email protected] TABLE DES MATIERES TABLE DES MATIERES ............................................................................................................... 2 SIGLES ET ABREVIATIONS .......................................................................................................... 6 LISTE DES FIGURES .................................................................................................................... 8 LISTE DES TABLEAUX ................................................................................................................ 9 RÉSUMÉ EXÉCUTIF .................................................................................................................. 11 CHAPITRE 1 : INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 13 1.1- Contexte et justification de l’étude ..................................................................................................... -

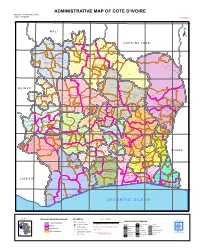

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP of COTE D'ivoire Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'ivoire 2Nd Edition

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF COTE D'IVOIRE Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'IVOIRE 2nd Edition 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W 11°0'0"N 11°0'0"N M A L I Papara Débété ! !. Zanasso ! Diamankani ! TENGRELA [! ± San Koronani Kimbirila-Nord ! Toumoukoro Kanakono ! ! ! ! ! !. Ouelli Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona ! ! Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko ! ! B U R K I N A F A S O !. Kouban Bougou ! Blésségué ! Sokoro ! Niéllé Tahara Tiogo !. ! ! Katogo Mahalé ! ! ! Solognougo Ouara Diawala Tienny ! Tiorotiérié ! ! !. Kaouara Sananférédougou ! ! Sanhala Sandrégué Nambingué Goulia ! ! ! 10°0'0"N Tindara Minigan !. ! Kaloa !. ! M'Bengué N'dénou !. ! Ouangolodougou 10°0'0"N !. ! Tounvré Baya Fengolo ! ! Poungbé !. Kouto ! Samantiguila Kaniasso Monogo Nakélé ! ! Mamougoula ! !. !. ! Manadoun Kouroumba !.Gbon !.Kasséré Katiali ! ! ! !. Banankoro ! Landiougou Pitiengomon Doropo Dabadougou-Mafélé !. Kolia ! Tougbo Gogo ! Kimbirila Sud Nambonkaha ! ! ! ! Dembasso ! Tiasso DENGUELE REGION ! Samango ! SAVANES REGION ! ! Danoa Ngoloblasso Fononvogo ! Siansoba Taoura ! SODEFEL Varalé ! Nganon ! ! ! Madiani Niofouin Niofouin Gbéléban !. !. Village A Nyamoin !. Dabadougou Sinémentiali ! FERKESSEDOUGOU Téhini ! ! Koni ! Lafokpokaha !. Angai Tiémé ! ! [! Ouango-Fitini ! Lataha !. Village B ! !. Bodonon ! ! Seydougou ODIENNE BOUNDIALI Ponondougou Nangakaha ! ! Sokoro 1 Kokoun [! ! ! M'bengué-Bougou !. ! Séguétiélé ! Nangoukaha Balékaha /" Siempurgo ! ! Village C !. ! ! Koumbala Lingoho ! Bouko Koumbolokoro Nazinékaha Kounzié ! ! KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Togoniéré ! Sirana -

Cote D'ivoire Summary Full Resettlement Plan (Frp)

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP PROJECT : GRID REINFORCEMENT AND RURAL ELECTRIFICATION PROJECT COUNTRY : COTE D’IVOIRE SUMMARY FULL RESETTLEMENT PLAN (FRP) Project Team : Mr. R. KITANDALA, Electrical Engineer, ONEC.1 Mr. P. DJAIGBE, Principal Energy Officer ONEC.1/SNFO Mr. M.L. KINANE, Principal Environmental Specialist ONEC.3 Mr. S. BAIOD, Consulting Environmentalist, ONEC.3 Project Team Sector Director: Mr. A.RUGUMBA, Director, ONEC Regional Director: Mr. A. BERNOUSSI, Acting Director, ORWA Division Manager: Mr. Z. AMADOU, Division Manager, ONEC.1, 1 GRID REIFORCEMENT AND RURAL ELECTRIFICATION PROJECT Summary FRP Project Name : GRID REIFORCEMENT AND RURAL ELECTRIFICATION PROJECT Country : COTE D’IVOIRE Project Number : P-CI-FA0-014 Department : ONEC Division: ONEC 1 INTRODUCTION This document presents the summary Full Resettlement Plan (FRP) of the Grid Reinforcement and Rural Electrification Project. It defines the principles and terms of establishment of indemnification and compensation measures for project affected persons and draws up an estimated budget for its implementation. This plan has identified 543 assets that will be affected by the project, while indicating their socio- economic status, the value of the assets impacted, the terms of compensation, and the institutional responsibilities, with an indicative timetable for its implementation. This entails: (i) compensating owners of land and developed structures, carrying out agricultural or commercial activities, as well as bearing trees and graves, in the road right-of-way for loss of income, at the monetary value replacement cost; and (ii) encouraging, through public consultation, their participation in the plan’s planning and implementation. 1. PROJECT DESCRIPTION AND IMPACT AREA 1.1. Project Description and Rationale The Grid Reinforcement and Rural Electrification Project seeks to strengthen power transmission infrastructure with a view to completing the primary network, ensuring its sustainability and, at the same time, upgrading its available power and maintaining its balance. -

Côte D'ivoire

Côte d’Ivoire Monthly Humanitarian Report October 2011 www.unocha.org The mission of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) is to mobilize and coordinate effective and principled humanitarian action in partnership with national and international actors. Coordination Saves Lives • Celebrating 20 years of coordinated humanitarian action October 2011 Côte d’Ivoire Humanitarian Bulletin | 2 Côte d’Ivoire Monthly Humanitarian Report Coordination Saves Lives No.1 | October 2011 HIGHLIGHTS ■ The number of Internally Displaced People (IDPs) on 35 sites across the country is gradually decreasing. ■ A National Committee for Coordination of Humanitarian Action (CNCAH) was established by ministerial decree (Minister of State, Employment, Social Affairs and Solidarity) on 5 October 2011. ■ Ivorian refugees in Liberia are spontaneously and gradually returning to their villages of origin in the Moyen Cavally region. ■ The Humanitarian Coordinator and the Ivorian Minister for Employment, Solidarity and Social Affairs visited several European capitals to mobilize support for humanitarian action in Côte d'Ivoire. ■ The Special Representative of the UN Secretary General in Côte d'Ivoire took office on 24 October. I. GENERAL CONTEXT During October, violent incidents took place in the towns of Issia, Guiglo and Bangolo in the West of the country. These incidents resulted in the displacement of an estimated 450 people according to the Protection Cluster. In the Lagunes region, there has been an upsurge of security incidents: several cases of armed robbery, home intrusion and theft are reported to have been committed by armed men in the districts of Anyama, Abobo and Yopougon, in Abidjan. This situation is reportedly due to the free circulation of firearms and to escapee- prisoners since the post-electoral crisis.