Z:\AISRI Special Projects\Assiniboine Narratives Web Volumes\SHIELDS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The North-West Rebellion 1885 Riel on Trial

182-199 120820 11/1/04 2:57 PM Page 182 Chapter 13 The North-West Rebellion 1885 Riel on Trial It is the summer of 1885. The small courtroom The case against Riel is being heard by in Regina is jammed with reporters and curi- Judge Hugh Richardson and a jury of six ous spectators. Louis Riel is on trial. He is English-speaking men. The tiny courtroom is charged with treason for leading an armed sweltering in the heat of a prairie summer. For rebellion against the Queen and her Canadian days, Riel’s lawyers argue that he is insane government. If he is found guilty, the punish- and cannot tell right from wrong. Then it is ment could be death by hanging. Riel’s turn to speak. The photograph shows What has happened over the past 15 years Riel in the witness box telling his story. What to bring Louis Riel to this moment? This is the will he say in his own defence? Will the jury same Louis Riel who led the Red River decide he is innocent or guilty? All Canada is Resistance in 1869-70. This is the Riel who waiting to hear what the outcome of the trial was called the “Father of Manitoba.” He is will be! back in Canada. Reflecting/Predicting 1. Why do you think Louis Riel is back in Canada after fleeing to the United States following the Red River Resistance in 1870? 2. What do you think could have happened to bring Louis Riel to this trial? 3. -

Tribal Strategies Against Violence: Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes Case Study

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Tribal Strategies Against Violence: Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes Case Study Author(s): V. Richard Nichols ; Anne Litchfield ; Ted Holappa ; Kit Van Stelle Document No.: 206034 Date Received: June 2004 Award Number: 97-DD-BX-0031 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Tribal Strategies Against Violence Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes Case Study Prepared by ORBIS Associates V. Richard Nichols Principal Investigator Anne Litchfield Senior Researcher/Editor Ted Holappa Investigator Kit Van Stelle Criminal Justice Consultant January 2002 NIJ # 97-DD-BX0031 This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Prepared for the National Institute of Justice, U.S. Department of Justice, by ORBIS Associates under contract # 97-DD- BX 0031. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. -

Medicine Wheels

The central rock pile was 14 feet high with several cairns spanned out in different directions, aligning to various stars. Astraeoastronomers have determined that one cairn pointed to Capella, the ideal North sky marker hundreds of years ago. At least two cairns aligned with the solstice sunrise, while the others aligned with the rising points of bright stars that signaled the summer solstice 2000 years ago (Olsen, B, 2008). Astrological alignments of the five satellite cairns around the central mound of Moose Mountain Medicine Wheel from research by John A. Eddy Ph.D. National Geographic January 1977. MEDICINE WHEELS Medicine wheels are sacred sites where stones placed in a circle or set out around a central cairn. Researchers claim they are set up according to the stars and planets, clearly depicting that the Moose Mountain area has been an important spiritual location for millennia. 23 Establishing Cultural Connections to Archeological Artifacts Archeologists have found it difficult to establish links between artifacts and specific cultural groups. It is difficult to associate artifacts found in burial or ancient camp sites with distinct cultural practices because aboriginal livelihood and survival techniques were similar between cultures in similar ecosystem environments. Nevertheless, burial sites throughout Saskatchewan help tell the story of the first peoples and their cultures. Extensive studies of archeological evidence associated with burial sites have resulted in important conclusions with respect to the ethnicity of the people using the southeast Saskatchewan region over the last 1,000 years. In her Master Thesis, Sheila Dawson (1987) concluded that the bison culture frequently using this area was likely the Sioux/ Assiniboine people. -

Rupturing the Myth of the Peaceful Western Canadian Frontier: a Socio-Historical Study of Colonization, Violence, and the North West Mounted Police, 1873-1905

Rupturing the Myth of the Peaceful Western Canadian Frontier: A Socio-Historical Study of Colonization, Violence, and the North West Mounted Police, 1873-1905 by Fadi Saleem Ennab A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Sociology University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2010 by Fadi Saleem Ennab TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... iii CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW ..................................................................... 8 Mythologizing the Frontier .......................................................................................... 8 Comparative and Critical Studies on Western Canada .......................................... 15 Studies of Colonial Policing and Violence in Other British Colonies .................... 22 Summary of Literature ............................................................................................... 32 Research Questions ..................................................................................................... 33 CHAPTER THREE: THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS ......................................... 35 CHAPTER -

Coordination and Related Constructions in Omaha-Ponca and in Siouan Languages Catherine Rudin

Chapter 15 Coordination and related constructions in Omaha-Ponca and in Siouan languages Catherine Rudin Syntactic constructions expressing semantic coordination vary widely across the Siouan language family. A case study of possible coordinating conjunctions in Omaha-Ponca demonstrates that distinguishing coordination from other means of expressing ‘and’ relations is a non-trivial problem. A survey of words translated as ‘and,’ ‘or,’ or ‘but’ in Siouan languages leads to the conclusion that neither co- ordinating conjunctions nor the syntactic structures containing them are recon- structable across the Siouan family. It is likely that Proto-Siouan lacked syntactic coordination. 1 Introduction All languages have ways of expressing additive, disjunctive, and adversative rela- tions among entities or propositions. In European languages these relations are expressed by two distinct syntactic means: coordination and subordination. In Siouan languages these two types of conjunction construction are also present, but the distinction between them is less robust and less clear; coordination may not have existed at all historically. Neither coordinating conjunctions (‘and,’ ‘or,’ ‘but’) nor the syntactic structures containing them are reconstructable across the Siouan family. I begin this examination of coordination in Siouan by defining coordination and discussing some of the issues involved in distinguishing coordinate from subordinate conjunction (§2). This is followed in§3 by a case study of additive coordination and coordinate-like constructions in Omaha-Ponca, the Siouan lan- guage with which I am most familiar. §4 is a survey of available data on coor- dination across all branches and most of the languages in the Siouan language family, with a summary table. -

Continuing to Support the Development of Healthy Self-Sufficient Communities

CONTINUING TO SUPPORT THE DEVELOPMENT OF HEALTHY SELF-SUFFICIENT COMMUNITIES Table of Contents BATC CDC Strategic Plan Page 3—4 Background Page 5 Message from the Chairman Page 6 Members of the Board & Staff Page 7-8 Grant Distribution Summary Page 9-14 Photo Collection Page 15—16 Auditor’s Report Page 17—23 Management Discussion and Analysis Page 24—26 Front Cover Photo Credit: Lance Whitecalf 2 BATC CDC Strategic Plan The BATC Community Development Corporation’s Strategic Planning sessions for 2010—2011 were held commencing September, 2009 with final draft approved on March 15, 2010. CORE VALUES Good governance practice Communication Improve quality of life Respect for culture Sharing VISION Through support of catchment area projects, the BATC CDC will provide grants for the development of healthy self-sufficient communities. Tagline – Continuing to support the development of healthy self-sufficient communities. MISSION BATC CDC distributes a portion of casino proceeds to communities in compliance with the Gaming Framework Agreement and core values. 3 BATC CDC Strategic Plan—continued Goals and Objectives CORE OBJECTIVE GOAL TIMELINE MEASUREMENT VALUE Good Govern- Having good policies Review once yearly May 31/10 Resolution receiving report and ance Practice Effective management team Evaluation Mar 31/11 update as necessary Having effective Board Audit July 31/11 Management regular reporting to Board Accountability/Transparency Auditor’s Management letter Compliant with Gaming Agreement Meet FNMR reporting timelines Communication Create -

Perspectives of Saskatchewan Dakota/Lakota Elders on the Treaty Process Within Canada.” Please Read This Form Carefully, and Feel Free to Ask Questions You Might Have

Perspectives of Saskatchewan Dakota/Lakota Elders on the Treaty Process within Canada A Dissertation Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Interdisciplinary Studies University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Leo J. Omani © Leo J. Omani, copyright March, 2010. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of the thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis was completed. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain is not to be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Request for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis, in whole or part should be addressed to: Graduate Chair, Interdisciplinary Committee Interdisciplinary Studies Program College of Graduate Studies and Research University of Saskatchewan Room C180 Administration Building 105 Administration Place Saskatoon, Saskatchewan Canada S7N 5A2 i ABSTRACT This ethnographic dissertation study contains a total of six chapters. -

Indian Band Revenue Moneys Order Décret Sur Les Revenus Des Bandes D’Indiens

CANADA CONSOLIDATION CODIFICATION Indian Band Revenue Moneys Décret sur les revenus des Order bandes d’Indiens SOR/90-297 DORS/90-297 Current to October 11, 2016 À jour au 11 octobre 2016 Last amended on December 14, 2012 Dernière modification le 14 décembre 2012 Published by the Minister of Justice at the following address: Publié par le ministre de la Justice à l’adresse suivante : http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca http://lois-laws.justice.gc.ca OFFICIAL STATUS CARACTÈRE OFFICIEL OF CONSOLIDATIONS DES CODIFICATIONS Subsections 31(1) and (3) of the Legislation Revision and Les paragraphes 31(1) et (3) de la Loi sur la révision et la Consolidation Act, in force on June 1, 2009, provide as codification des textes législatifs, en vigueur le 1er juin follows: 2009, prévoient ce qui suit : Published consolidation is evidence Codifications comme élément de preuve 31 (1) Every copy of a consolidated statute or consolidated 31 (1) Tout exemplaire d'une loi codifiée ou d'un règlement regulation published by the Minister under this Act in either codifié, publié par le ministre en vertu de la présente loi sur print or electronic form is evidence of that statute or regula- support papier ou sur support électronique, fait foi de cette tion and of its contents and every copy purporting to be pub- loi ou de ce règlement et de son contenu. Tout exemplaire lished by the Minister is deemed to be so published, unless donné comme publié par le ministre est réputé avoir été ainsi the contrary is shown. publié, sauf preuve contraire. -

Water Quality Report

Central Assiniboine Watershed Integrated Watershed Management Plan - Water Quality Report October 2010 Central Assiniboine Watershed – Water Quality Report Water Quality Investigations and Routine Monitoring: This report provides an overview of the studies and routine monitoring which have been undertaken by Manitoba Water Stewardship’s Water Quality Management Section within the Central Assiniboine watershed. There are six long term water quality monitoring stations (1965 – 2009) within the Central Assiniboine Watershed. These include the Assiniboine, Souris and Cypress Rivers. There are also ten stations not part of the long term water quality monitoring program in which some data are available for alternate locations on the Assiniboine, Souris, and Little Saskatchewan Rivers. The Central Assiniboine River watershed area is characterized primarily by agricultural crop land, industry, urban and rural centres. All these land uses have the potential to negatively impact water quality, if not managed appropriately. Cropland can present water quality concerns in terms of fertilizer and pesticide runoff entering surface water. There are a number of large industrial operations in the Central Assiniboine Watershed, these present water quality concerns in terms of wastewater effluent and industrial runoff. Large centers and rural municipalities present water quality concerns in terms of wastewater treatment and effluent. The tributary of most concern in the Central Assiniboine watershed is the Assiniboine River, as it is the largest river in the watershed. The area surrounding the Assiniboine River is primarily agricultural production yielding a high potential for nutrient and bacteria loading. The Assiniboine River serves as the main drinking water source for many residents in this watershed. In addition, the Assiniboine River drains into Lake Winnipeg, and as such has been listed as a vulnerable water body in the Nutrient Management Regulation under the Water Protection Act. -

Ring Games Stage 1 Desired Results Established Goals Health Enhancement Standard 7, Benchmark 4.3: Experience Enjoyment Through Physical Activity

Model Lesson Plan Health Enhancement Traditional Games Grade 3 Ring Games Stage 1 Desired Results Established Goals Health Enhancement Standard 7, Benchmark 4.3: Experience enjoyment through physical activity. Essential Understandings 3: The ideologies of Native traditional beliefs and spirituality persist into modern day life as tribal cultures, traditions, and languages are still practiced by many American Indian people and are incorporated into how tribes govern and manage their affairs. Additionally, each tribe has its own oral history beginning with their origins which are as valid as written histories. These histories pre-date the “discovery” of North America. Understandings Essential Questions 1. There were similar Indian games with 1. What is the main idea of games of “ring and different values for the outcomes of the pin”? games. 2. How can the skill of “ring and pin” be used in the modern world? Students will be able to… Students will know… 1. Move through four stations of manual 1. Four examples of “ring and pin” games. dexterity (eye-hand coordination) and learn (Assiniboine, Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, concepts of tribal values and origination. and Zuni) 2. The values associated with playing “ring and pin” games. Stage 2 Assessment Evidence Performance Tasks 1. The student will practice each of the four games, rotating through stations. 2. The student will be able to explain the differences in rules. 3. The student will be able to tell what values “winning” meant in the historical playing of the games. Page 1 of 4 12/29/2008 Health Enhancement Traditional Games Grade 3 Ring Games (continued) Stage 3 Learning Plan Teaching Area (indoors or outdoors or in a gym) 50’ x 50’ for 24 students in pairs, six per station. -

Download Download

The Southern Algonquians and Their Neighbours DAVID H. PENTLAND University of Manitoba INTRODUCTION At least fifty named Indian groups are known to have lived in the area south of the Mason-Dixon line and north of the Creek and the other Muskogean tribes. The exact number and the specific names vary from one source to another, but all agree that there were many different tribes in Maryland, Virginia and the Carolinas during the colonial period. Most also agree that these fifty or more tribes all spoke languages that can be assigned to just three language families: Algonquian, Iroquoian, and Siouan. In the case of a few favoured groups there is little room for debate. It is certain that the Powhatan spoke an Algonquian language, that the Tuscarora and Cherokee are Iroquoians, and that the Catawba speak a Siouan language. In other cases the linguistic material cannot be positively linked to one particular political group. There are several vocabularies of an Algonquian language that are labelled Nanticoke, but Ives Goddard (1978:73) has pointed out that Murray collected his "Nanticoke" vocabulary at the Choptank village on the Eastern Shore, and Heckeweld- er's vocabularies were collected from refugees living in Ontario. Should the language be called Nanticoke, Choptank, or something else? And if it is Nanticoke, did the Choptank speak the same language, a different dialect, a different Algonquian language, or some completely unrelated language? The basic problem, of course, is the lack of reliable linguistic data from most of this region. But there are additional complications. It is known that some Indians were bilingual or multilingual (cf. -

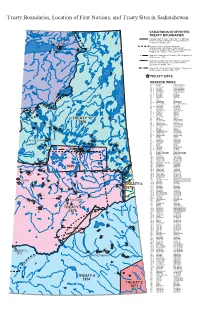

Treaty Boundaries Map for Saskatchewan

Treaty Boundaries, Location of First Nations, and Treaty Sites in Saskatchewan VARIATIONS IN DEPICTED TREATY BOUNDARIES Canada Indian Treaties. Wall map. The National Atlas of Canada, 5th Edition. Energy, Mines and 229 Fond du Lac Resources Canada, 1991. 227 General Location of Indian Reserves, 225 226 Saskatchewan. Wall Map. Prepared for the 233 228 Department of Indian and Northern Affairs by Prairie 231 224 Mapping Ltd., Regina. 1978, updated 1981. 232 Map of the Dominion of Canada, 1908. Department of the Interior, 1908. Map Shewing Mounted Police Stations...during the Year 1888 also Boundaries of Indian Treaties... Dominion of Canada, 1888. Map of Part of the North West Territory. Department of the Interior, 31st December, 1877. 220 TREATY SITES RESERVE INDEX NO. NAME FIRST NATION 20 Cumberland Cumberland House 20 A Pine Bluff Cumberland House 20 B Pine Bluff Cumberland House 20 C Muskeg River Cumberland House 20 D Budd's Point Cumberland House 192G 27 A Carrot River The Pas 28 A Shoal Lake Shoal Lake 29 Red Earth Red Earth 29 A Carrot River Red Earth 64 Cote Cote 65 The Key Key 66 Keeseekoose Keeseekoose 66 A Keeseekoose Keeseekoose 68 Pheasant Rump Pheasant Rump Nakota 69 Ocean Man Ocean Man 69 A-I Ocean Man Ocean Man 70 White Bear White Bear 71 Ochapowace Ochapowace 222 72 Kahkewistahaw Kahkewistahaw 73 Cowessess Cowessess 74 B Little Bone Sakimay 74 Sakimay Sakimay 74 A Shesheep Sakimay 221 193B 74 C Minoahchak Sakimay 200 75 Piapot Piapot TREATY 10 76 Assiniboine Carry the Kettle 78 Standing Buffalo Standing Buffalo 79 Pasqua