Terra Infirma: Stubborn Affect and Artifactual Traces1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tipatshimun 4E Trimestre 2008.Pdf

OCTOBRE-NOVEMBRE 2008 VOLUME 5 NUMÉRO 4 P. 5 C’est officiel ! La flamme olympique s’en vient à Essipit, et lors de son passage, notre Conseil de bande livrera un message bien spécial que lui a demandé de transmettre l’une des quatre Premières Nations hôtes des Jeux de Vancouver, la nation Squamish. P. 7 C’est dans un petit restaurant de Baie Ste- Catherine que s’est déroulée une « rencontre au sommet » portant sur la Grande Alliance signée tout près de là par Champlain et le grand chef innu, Anadabijou. P. 3 C’est un grand événement qui s’est déroulé au Musée de la civilisation, alors qu’on procédait au tout premier lancement au Québec, d’un livre d’art réalisé par un peintre autochtone. Intitulé Je me souviens L’entente entre Essipit et Boisaco fait des petits : des premiers contacts – De l’ombre à la lumière, ce livre est l’œuvre d’Ernest Dominique, mieux connu déjà des mesures d’accommodement sont sous son nom d’artiste d’Aness. On l’aperçoit ici en compagnie de notre Catherine Moreau bien à nous. en place prévoyant notamment, une Voir page 6 relocalisation du site traditionnel du lac Maigre vers le lac Mongrain. Tipatshimun ENTENTE AVEC BOISACO ESSIPIT DÉPOSE DES AVIS DE PRÉFAISABILITÉ Nos valeurs sont-elles Deux projets de mini-centrales respectées? en Haute-Côte-Nord ans une lettre datée du 16 octobre communément appelé Les portes de l’enfer. D2008, le chef Denis Ross du Conseil Il aurait une puissance installée de 36 MW et des Innus Essipit, avise le préfet Jean-Ma- une production annuelle de 119 400 MWh. -

Premières Nations Et Inuits Du Québec 84 ° 82° 80° 78° 76° 74° 72° 70° 68° 66° 64° 62° 60° 58° 56° 54° 52° 62°

PREMIÈRES NATIONS ET INUITS DU QUÉBEC 84 ° 82° 80° 78° 76° 74° 72° 70° 68° 66° 64° 62° 60° 58° 56° 54° 52° 62° Ivujivik nations Salluit Détroit d’Hudson Abénaquis Kangiqsujuaq les 11 Algonquins Akulivik Attikameks 60° Quaqtaq Cris Mer du Labrador Hurons-Wendats Puvirnituq Kangirsuk Innus (Montagnais) Baie d’Ungava Malécites Micmacs Aupaluk Mohawks Inukjuak Naskapis 58 ° Kangiqsualujjuaq Tasiujaq Inuits T ra cé * Inuits de Chisasibi Kuujjuaq d e 1 9 2 7 d u C o n s Baie d’Hudson e i l p r Umiujaq i v 56 ° é ( n o n d é n i t 10 i f ) Kuujjuarapik Whapmagoostui Kawawachikamach Matimekosh • 54 ° Lac-John Chisasibi Schefferville * Radisson • Happy Valley-Goose Bay • Wemindji Baie James Fermont • 52 ° Eastmain Tracé de 1927 du Conseil privé (non dénitif) Lourdes-de-Blanc-Sablon• Waskaganish Nemaska Pakuashipi 09 Havre- La Romaine Uashat Saint-Pierre 50 ° Maliotenam Nutashkuan Natashquan Mistissini Mingan • Sept-Îles• • • Chibougamau Port-Cartier • Oujé-Bougoumou Waswanipi Île d'Anticosti Pikogan Baie-Comeau 02 • Pessamit Rouyn-Noranda Obedjiwan •Dolbeau-Mistassini Gespeg • • Gaspé 48 ° Val-d’Or Forestville Fleuve Saint-Laurent • Lac-Simon • • Gesgapegiag 11 Alma Essipit • Rimouski Golfe du Saint-Laurent Timiskaming Mashteuiatsh Saguenay• 08 01 Listuguj Kitcisakik Tadoussac• Cacouna Winneway Wemotaci • Whitworth Rivière- Lac-Rapide 04 •La Tuque du-Loup Hunter’s Point 03 Manawan Wendake Kebaowek Route 15 • Québec Voie ferrée 46 ° 07 14 Trois-Rivières Kitigan Zibi • Wôlinak 12 Région administrative Frontière internationale 17 Kanesatake Odanak -

Introduction Inuit

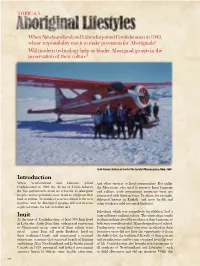

TOPIC 6.5 When Newfoundland and Labrador joined Confederation in 1949, whose responsibility was it to make provisions for Aboriginals? Will modern technology help or hinder Aboriginal groups in the preservation of their culture? 6.94 School children in front of the Grenfell Mission plane, Nain, 1966 Introduction When Newfoundland and Labrador joined and other services to Inuit communities. But unlike Confederation in 1949, the Terms of Union between the Moravians, who tried to preserve Inuit language the two governments made no reference to Aboriginal and culture, early government programs were not peoples and no provisions were made to safeguard their concerned with these matters. Teachers, for example, land or culture. No bands or reserves existed in the new delivered lessons in English, and most health and province and its Aboriginal peoples did not become other workers could not speak Inuktitut. registered under the federal Indian Act. Schooling, which was compulsory for children, had a Inuit huge influence on Inuit culture. The curriculum taught At the time of Confederation, at least 700 Inuit lived students nothing about their culture or their language, so in Labrador. Aside from their widespread conversion both were severely eroded. Many dropped out of school. to Christianity, many aspects of Inuit culture were Furthermore, young Inuit who were in school in their intact – many Inuit still spoke Inuktitut, lived on formative years did not have the opportunity to learn their traditional lands, and maintained a seasonal the skills to live the traditional lifestyle of their parents subsistence economy that consisted largely of hunting and grandparents and became estranged from this way and fishing. -

North American Megadam Resistance Alliance

North American Megadam Resistance Alliance May 18, 2020 Christopher Lawrence U.S. Department of Energy Management and Program Analyst Transmission Permitting and Technical Assistance Office of Electricity Christopher.Lawrence.hq.doe.gov Re: Comments on DOE Docket No. PP-362-1: Champlain Hudson Power Express, Inc. and CHPE, LLC: Application to Rescind Presidential Permit and Application for Presidential Permit Dear Mr. Lawrence, The Sierra Club Atlantic Chapter and North American Megadam Resistance Alliance submit these comments on the above-referenced application of Champlain Hudson Power Express, Inc. (CHPEI) and CHPE, LLC (together, the Applicants) to transfer to CHPE, LLC ownership of the facilities owned by CHPEI and authorized for cross-border electric power transmission via a high voltage direct current line (the Project) by Presidential Permit No. PP- 362, dated October 6, 2014 (PP-362 or the Permit) .1 The Project is being developed by TDI, a Blackstone portfolio company. www.transmissiondevelopers.com Blackstone is a private investment firm with about $500 billion under management. www.blackstone.com The Sierra Club Atlantic Chapter, headquartered Albany New York, is responsible for the Sierra Club’s membership and activities in New York State and works on a variety of environmental issues. The Sierra Club is a national environmental organization founded in 1892. 1 On April 6, 2020, the Applicants requested that the Department of Energy (DOE) amend, or in the alternative, rescind and reissue PP-362 to enable the transfer of the Permit from CHPEI to its affiliate CHPE, LLC (the Application). On April 16, 2020, the Department of Energy (DOE) issued a Notice of “Application to Rescind Presidential Permit; Application for Presidential Permit; Champlain Hudson Power Express, Inc. -

Innu-Aimun Legal Terms Kaueueshtakanit Aimuna

INNU-AIMUN LEGAL TERMS (criminal law) KAUEUESHTAKANIT AIMUNA Sheshatshiu Dialect FIRST EDITION, 2007 www.innu-aimun.ca Innu-aimun Legal Terms (Criminal Law) Kaueueshtakanit innu-aimuna Sheshatshiu Dialect Editors / Ka aiatashtaht mashinaikannu Marguerite MacKenzie Kristen O’Keefe Innu collaborators / Innuat ka uauitshiaushiht Anniette Bartmann Mary Pia Benuen George Gregoire Thomas Michel Anne Rich Audrey Snow Francesca Snow Elizabeth Williams Legal collaborators / Kaimishiht ka uitshi-atussemaht Garrett O’Brien Jason Edwards DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE GOVERNMENT OF NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR St. John’s, Canada Published by: Department of Justice Government of Newfoundland and Labrador St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada First edition, 2007 Printed in Canada ISBN 978-1-55146-328-5 Information contained in this document is available for personal and public non-commercial use and may be reproduced, in part or in whole and by any means, without charge or further permission from the Department of Justice, Newfoundland and Labrador. We ask only that: 1. users exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the material reproduced; 2. the Department of Justice, Newfoundland and Labrador be identified as the source department; 3. the reproduction is not represented as an official version of the materials reproduced, nor as having been made in affiliation with or with the endorsement of the Department of Justice, Newfoundland and Labrador. Cover design by Andrea Jackson Printing Services by Memorial University of Newfoundland Foreword Access to justice is a cornerstone in our justice system. But it is important to remember that access has a broad meaning and it means much more than physical facilities. One of the key considerations in delivering justice services in Inuit and Innu communities is improving access through the use of appropriate language services. -

Iron Ore Company of Canada New Explosives Facility, Labrador City

IRON ORE COMPANY OF CANADA NEW EXPLOSIVES FACILITY, LABRADOR CITY Environmental Assessment Registration Pursuant to the Newfoundland & Labrador Environmental Protection Act (Part X) Submitted by: Iron Ore Company of Canada 2 Avalon Drive Labrador City, Newfoundland & Labrador A2V 2Y6 Canada Prepared with the assistance of: GEMTEC Consulting Engineers and Scientists Limited 10 Maverick Place Paradise, NL A1L 0J1 Canada May 2019 Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................1 1.1 Proponent Information ...............................................................................................3 1.2 Rationale for the Undertaking .................................................................................... 5 1.3 Environmental Assessment Process and Requirements ............................................ 7 2.0 PROJECT DESCRIPTION ..............................................................................................8 2.1 Geographic Location ..................................................................................................8 2.2 Land Tenure ............................................................................................................ 10 2.3 Alternatives to the Project ........................................................................................ 10 2.4 Project Components ................................................................................................ 10 2.4.1 Demolition and -

Davis Inlet in Crisis: Will the Lessons Ever Be Learned?

DAVIS INLET IN CRISIS: WILL THE LESSONS EVER BE LEARNED? Harold Press P.O. Box 6342, Station C St. John's, Newfoundland Canada, A1C 6J9 Abstract / Resume The author reviews the history of the Mushuau Innu who now live at Davis Inlet on the Labrador coast. He examines the policy context of the contem- porary community and looks at the challenges facing both the Innu and governments in the future. L'auteur réexamine l'histoire des Mushuau Innu qui habitent à présent à Davis Inlet sur la côète de Labrador. Il étudie la politique de la communauté contemporaine et considère les épreuves qui se présenteront aux Innu et aux gouvernements dans l'avenir. 188 Harold Press We have only lived in houses for twenty-five years, and we have seldom asked ourselves, "what should an Innu commu- nity be like? What does community mean to us as a people whose culture is based in a nomadic past, in six thousand years of visiting every pond and river valley in Nitassinan? - Hearing the Voices While the front pages of our local newspapers are replete with accounts of violence, poverty and abuse throughout the world, not often do we encounter cases, particularly in this country, of such unconditional destruc- tion that have led to the social disintegration of entire communities. One such case was Grassy Narrows, starkly and movingly brought to our collective attention by Shkilnyk (1985). The story of Grassy Narrows is one of devastation, impoverishment, and ruin. Shkilnyk describes her experi- ences in the small First Nation's community this way: I could never escape the feeling that I had been parachuted into a void - a drab and lifeless place in which the vital spark of life had gone out. -

Rapport Rectoverso

HOWSE MINERALS LIMITED HOWSE PROJECT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT – (APRIL 2016) - SUBMITTED TO THE CEAA 11 LITERATURE CITED AND PERSONAL COMMUNICATIONS Personal Communications André, D., Environmental Coordinator, MLJ, September 24 2014 Bouchard, J., Sécurité du Québec Director, Schefferville, September 26 2014 Cloutier, P., physician in NNK, NIMLJ and Schefferville, September 24 2014 Coggan, C. Atmacinta, Economy and Employment – NNK, 2013 and 2014 (for validation) Corbeil, G., NNK Public Works, October 28 2014 Cordova, O., TSH Director, November 3 2014 Côté, S.D., Localization of George River Caribou Herd Radio-Collared Individuals, Map dating from 2014- 12-08 from Caribou Ungava Einish, L., Centre de la petite enfance Uatikuss, September 23 2015 Elders, NNK, September 26 2014 Elders, NIMLJ, September 25 2014 Fortin, C., Caribou data, December 15 2014 and January 22 2014 Gaudreault, D., Nurse at the CLSC Naskapi, September 25 2014 Guanish, G., NNK Environmental Coordinator, September 22 2014 ITUM, Louis (Sylvestre) Mackenzie family trapline holder, 207 ITUM, Jean-Marie Mackenzie family, trapline holder, 211 Jean-Hairet, T., Nurse at the dispensary of Matimekush, personal communication, September 26 2014 Jean-Pierre, D., School Principal, MLJ, September 24 2014 Joncas, P., Administrator, Schefferville, September 22 2014 Lalonde, D., AECOM Project Manager, Environment, Montreal, November 10 2015 Lévesque, S., Non-Aboriginal harvester, Schefferville, September 25 2014 Lavoie, V., Director, Société de développement économique montagnaise, November 3 2014 Mackenzie, M., Chief, ITUM, November 3 2014 MacKenzie, R., Chief, Matimekush Lac-John, September 23 and 24 2014 Malec, M., ITUM Police Force, November 5 2014 Martin, D., Naskapi Police Force Chief, September 25 2014 Michel, A. -

Bottin Des Organismes Du Lac-Saint-Jean PREMIÈRE ÉDITION | 2020-2021

Bottin des organismes du Lac-Saint-Jean PREMIÈRE ÉDITION | 2020-2021 Alexis Brunelle-Duceppe Bottin des organismes du Lac-Saint-Jean 1 Première éditionDéputé | 2020-2021 de Lac-Saint-Jean Mot du député Chères citoyennes, Chers citoyens, Ouf! Quelle année mouvementée vivons-nous…! Toutes et tous ont fait des sacrifices pour passer à travers ces temps difficiles et bon nombre de gens dévoués ont pris le temps d’aider leur prochain. Que ce soit en se portant volontaire pour travailler dans les CHSLD, en faisant l’épicerie pour leurs voisins ou tout simplement en restant à la maison, les Jeannois et les Québécois ont montré à quel point ils avaient à cœur leur communauté. Cet engagement envers notre milieu, il est aussi porté au jour le jour par les travailleuses et les travailleurs des organismes communautaires. Ces gens œuvrent pour le bien commun et offrent des services de première ligne à tous les citoyens, quelle que soit leur situation socio-économique. Je suis très fier du livret que vous tenez entre vos mains, car il vous permettra d’entrer en contact avec des personnes qui peuvent vous aider. Cette première édition du Bottin des organismes répertorie donc les nombreux organismes de la circonscription Lac-Saint-Jean. De plus, vous remarquerez que la feuille centrale de ce document est détachable et peut servir à m’écrire gratuitement. Comme toujours, je m’engage à répondre à vos lettres et je suis toujours à l’affût des idées que vous me soumettez. D’ailleurs, je suis heureux de vous présenter les dessins gagnants du concours de la Fête nationale. -

Rapport Annuel 2017-2018

Couverture La couverture du rapport annuel 2017-2018 rappelle le Tshishtekahikan, le calendrier 2018-2019, qui souligne l’Année internationale des droits des peuples autochtones qui sera célébrée en 2019. Il s’agit d’une opportunité pour rappeler le caractère incontournable de la reconnaissance des droits des Premières Nations et pour sensibiliser à l’importance de la Déclaration des Nations Unies sur les droits des peuples autochtones. Pekuakamiulnuatsh Takuhikan 1671, rue Ouiatchouan Mashteuiatsh (Québec) G0W 2H0 Téléphone : 418 275-2473 Courriel : [email protected] Internet : www.mashteuiatsh.ca © Pekuakamiulnuatsh Takuhikan, 2018 Tous droits réservés. Toute reproduction ou diffusion du présent document, sous quelque forme ou par quelque procédé que ce soit, même partielle, est strictement interdite sans avoir obtenu, au préalable, l’autorisation écrite de Pekuakamiulnuatsh Takuhikan. 2 TABLE DES MATIÈRES Katakuhimatsheta Conseil des élus ........................................................................................................................................................................................................5 Tshitshue Takuhimatsheun Direction générale ...............................................................................................................................................................................................23 Katshipahikanish kamashituepalitakanitsh pakassun Ilnu Tshishe Utshimau Bureau du développement de l'autonomie gourvernementale ..................................................................................................26 -

Death and Life for Inuit and Innu

skin for skin Narrating Native Histories Series editors: K. Tsianina Lomawaima Alcida Rita Ramos Florencia E. Mallon Joanne Rappaport Editorial Advisory Board: Denise Y. Arnold Noenoe K. Silva Charles R. Hale David Wilkins Roberta Hill Juan de Dios Yapita Narrating Native Histories aims to foster a rethinking of the ethical, methodological, and conceptual frameworks within which we locate our work on Native histories and cultures. We seek to create a space for effective and ongoing conversations between North and South, Natives and non- Natives, academics and activists, throughout the Americas and the Pacific region. This series encourages analyses that contribute to an understanding of Native peoples’ relationships with nation- states, including histo- ries of expropriation and exclusion as well as projects for autonomy and sovereignty. We encourage collaborative work that recognizes Native intellectuals, cultural inter- preters, and alternative knowledge producers, as well as projects that question the relationship between orality and literacy. skin for skin DEATH AND LIFE FOR INUIT AND INNU GERALD M. SIDER Duke University Press Durham and London 2014 © 2014 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Arno Pro by Copperline Book Services, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Sider, Gerald M. Skin for skin : death and life for Inuit and Innu / Gerald M. Sider. pages cm—(Narrating Native histories) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978- 0- 8223- 5521- 2 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978- 0- 8223- 5536- 6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Naskapi Indians—Newfoundland and Labrador—Labrador— Social conditions. -

Tipatshimun Fevrier 2015 Essipit Complet.Pdf

ESSIPIT Page 2 C’est le 20 novembre qu’avait lieu l’évé- nement portes ouvertes de la nouvelle section du Centre administratif de la communauté d’Essipit. Page 3 Lancement du calendrier « ESHE » du Regroupement PETAPAN. Pages 4 et 5 Pascale Chamberland, Mélissa Ross, Annie Ashini et Johanne Bouchard se sont bien amusées. Le Conseil de bande honore certains de ses employés lors de son party de Noël. Page 7 Une belle année qui se termine avec la Une équipe de la Première Nation des Innus Essipit effectue des fouilles archéologiques de sauvetage au venue du père Noël. site « Lavoie » des Bergeronnes. Tipatshimun JOURNÉE PORTES OUVERTES Visite de la nouvelle aile du CentreCentre administratifadministratif À ll’entrée’entrée ddee llaa nnouvelleouvelle ppartie,artie, lleses eemployésmployés aaccueillentccueillent nnosos vvisiteurs.isiteurs. JJean-Françoisean-François BBoulianne,oulianne, UUnn bbuffetuffet a éétété sserviervi ddansans llaa nnouvelleouvelle ssallealle ddee rréunionéunion « UUtatakuntatakun »».. LLucuc CChartré,hartré, FFlorencelorence PParcoretarcoret eett PPierreierre TTremblay.remblay. Plus de 60 personnes ont par- De fond en comble de réunion appelée Utatakun et un étaient conviés à un buffet disposé ticipé à la visite de la nouvelle Dès 15 h 30, des invités se sont poste de service où sont situés une dans la salle Utatakun. Lorsque tous aile du Centre administratif Innu présentés dans le hall d’entrée où ils photocopieuse et une imprimante. furent arrivés, le chef Dufour les a Tshitshe Utshimau qui a eu lieu furent accueillis