Specialty Malt Contributions to Wort and Beer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brewing Grains What Is Malt?

612.724.4514 [email protected] www.aperfectpint.net Brewing Grains Brewing grains are the heart and soul of beer. Next to water they make up the bulk of brewing ingredients. Brewing grains provide the sugars that yeast ferment. They are the primary source of beer color and a major contributor to beer flavor, aroma, and body. Proteins in the grains give structure to beer foam and minerals deliver many of the nutrients essential to yeast growth. By far the most common brewing grain is malted barley or barley malt, but a variety of other grains, both malted and unmalted, are also used including wheat, corn, rice, rye, and oats. What is Malt? To put it plainly, malt is cereal grain that has undergone the malting process. In the simplest terms, malting is the controlled germination and kilning of grain. Malting develops the diastatic enzymes that accomplish the conversion of starch to sugar during brewing and begins a limited process of conversion that makes the starches more accessible to the brewer. Malting also gives brewing grains their distinctive colors and flavors. Only the highest quality grain, called brewing grade, is selected for malting. Brewing grade grain is selected for, among other things, high starch content, uniform kernel size, low nitrogen content, and high diastatic power. Diastatic power is the ability of grains to break down complex starch molecules into simpler sugars for brewing. It is determined by the amount of diastatic enzymes in the grain. Barley is the most commonly malted grain, but other grains like wheat and rye are also malted. -

Breakdown of a Malt COA

Breakdown of a Malt COA Bucket Analysis Approach Presenters Tyler Schoales Mike Heinrich Craft Malt Specialist – NA Craft Sales Manager Country Malt Group Great Western Malting Breakdown of a Malt COA Agenda Overview of Malting and Modification Certificate of Analysis Breakdown Bucketing Analysis • Protein Dependent Specifications • Carbohydrate Dependent Specifications • Enzyme Package Specifications • Color Breakdown of a Malt COA Malting and Breakdown of Bucketing Modification COA Analysis Malting and the Certificate of Analysis • Malting is the controlled germination and kilning of a seed to produce the desirable brewing characteristics • Maltsters create ideal growing conditions for barley to germinate and drive modification • “Modification” is the biochemical breakdown of cell wall structures, and protein matrices in order to gain access to the starch reserves held within the endosperm • A malt Certificate of Analysis (COA) lists the results from a suite of standardized tests that serve to indicate how the malt will perform. Breakdown of a Malt COA Malting and Breakdown of Bucketing Modification COA Analysis Breakdown of the COA Malt Sieve Analysis (Assortment) • Plump kernels provide more extract than thinner kernels • Roller mill gaps are set according to the mean kernel size • A broad distribution can make mill setting difficult → poor extract recovery in the brewery • Typical analysis – 7/64 + 6/64’s (PLUMP’s) > 90% • Consistency is the key Malt Sieve Analysis (Breakage) • Damaged husks will form a poor filter bed • Fines formed -

Evaluation of Saccharifying Methods for Alcoholic Fermentation of Starchy Substrates Alice Lee Iowa State College

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1955 Evaluation of saccharifying methods for alcoholic fermentation of starchy substrates Alice Lee Iowa State College Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Biochemistry Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Alice, "Evaluation of saccharifying methods for alcoholic fermentation of starchy substrates " (1955). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 13626. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/13626 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. ® UMI EVALUATION OF SACCHARIFYING METHODS FOR ALCOHOLIC FERMENTATION OF STARCHY SUBSTRATES by Alice Lee A Dlseertatlon Submitted to the Graduate Faculty In Partial Fulfillment of The RequirementB for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major Subjects Blochensletry Approved: Signature was redacted for privacy. In Charge of Major Work Signature was redacted for privacy. Head of Major Department Signature was redacted for privacy. Dean of Graduate College Iowa State College 1955 UMI Number: DP12815 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

WHEAT MALT in BREWING Viking Malt Malt Types

WHEAT MALT IN BREWING Viking malt malt types • pale brewing malts • dark brewing malts • pale caramel malts • dark caramel malts • roasted products • other malts like wheat malt Wheat as a raw material • wheat has no husk • requirements for malting wheat are same as for barley • two kinds of wheat available • A- type used mainly for baking • B- type used mainly for feed • brewing varieties do not exist at the moment • malting process does not differ much from pilsner malt production • faster water uptake in steep • germination in cool conditions • final kilning temperature 80 – 85 °C Production of wheat malt Barley / Wheat / Rye Steeping Germination Saccharification Roasting Roasting Kilning Pale Dark Roasted malt Caramel brewing brewing and barley malts malts malts Wheat vs barley Barley Wheat Unit Protein 11 12 % dm Fat 3 3 % dm Minerals 2,9 1,8 % dm Starch 63 64 % dm Beta-glucans 3,5 0,3 % dm Pentosans 9 8,5 % dm Source: EBC Manual of Good Practice, Malting Technology Wheat wort • Example of high gravity wort results: Analysis unit 100 % PM 20 % Wheat malt 40 % Wheat malt Extract m-% 16,19 16,29 16,23 Yield % / dm. 81,7 83,6 84,6 Soluble N mg / 100 g 815 836 853 pH 5,6 5,6 5,7 Colour °EBC 7,5 8,0 9,0 Haze F.U. EBC 5,2 8,5 10,8 ß-glucans mg / l 150 116 105 FAN mg / l 334 302 258 App. degree of ferm. % 85,9 84,6 83,8 Büchner-filtrate 15 min g 94,9 89,1 82,1 Saccharification min / °C 5/72 5/72 5/72 Wheat wort • Example of high gravity wort sugar compositions: fructose (% glucose maltose (% maltotriose fermentable dm) (% dm) dm) (% dm) -

How-To-Partial-Mash.Pdf

Partial Mashing Partial mashing, sometimes referred to as mini-mashing, may appear similar to steeping specialty grains, but the crucial difference is partial mashing actively converts a bulk of the grain starches into fermentable sugars while steeping grains provide minimal fermentable sugars to the wort. In other words, the base malts that are soaked in a partial mash usually replace up to half of the malt extract normally used in an all extract or extract with specialty grain recipes. The benefits of partial mashing affect brewers of all skill levels. New brewers experiment with partial mashes to get comfortable with the mashing process before moving to all-grain brewing. Apartment and small-space brewers are attracted to partial mashing because of the minimal equipment it requires while still being able to mash some base malt. Homebrewers of all skill levels who utilize mostly extract will sometimes partial mash in order to use grains that require a mash step. Converting to Partial Mash For the purpose of this partial-mash example, we will be using the recipe used for the extract with specialty grain tutorial, Port O'Palmer Porter. In this recipe, there is 6.6 lb (3 kg), or two cans, of liquid pale malt extract, where most of the fermentable sugar for the wort is derived. For the partial-mash, reduce the liquid malt extract to 3.3 lb (1.5 kg), or one can, and the remaining fermentable sugars will be extracted from pale base malt during a mini-mash process. To determine the amount of base malt needed to replace extract, two conversions can be used. -

Sweeteners and Diabetes

PEDIATRIC DIABETES INFORMATION Sweeteners and Diabetes Sweeteners (like sugar, Equal®, sorbitol) are added so that foods taste sweeter. Some sweeteners have carbohydrate in them and some do not. Sweeteners that contain carbohydrate will raise blood sugar. Artificial Sweeteners Sugar Alcohols Sugars (no calories) (have calories) (have calories) • Do NOT have carbohydrate • Have carbohydrate • Have carbohydrate • Do not raise blood sugar • May raise blood • Raise blood sugar sugar Scientific Name Common Name Hydrogenated starch • Agave nectar hydrolysates: • Corn sweetener Acesulfame K Sweet One®, Sunette® • Isomalt • Corn syrup • Date sugar Aspartame Equal®, Nutrasweet®, • Lactitol NatraTaste® • Maltitol • Dextrose • Mannitol • Evaporated cane ® Saccharine Sugar-Twin , • Sorbitol juice Sweet’n’Low®, • Xylitol • Fructose Sucaryl®, Sweet 10® • Erithritol • Glucose • High fructose corn Sucralose Splenda® May cause gas, syrup Stevia/ diarrhea, and • Honey Rebaudioside Sweet Leaf®, cramping. • Invert sugar Sun Crystals®, Steviva®, • Lactose ® ® Truvia , Purevia • Malt, maltose, malt sugar, malt syrup Neotame None (used as food additive only) • Maple syrup, maple sugar • Molasses • Raw sugar • Rice syrup • Sucrose • Turbinado sugar PEDIATRIC DIABETES INFORMATION Sweeteners and Food Labels Be aware of the total carbohydrate in foods that use sweeteners. Many foods that say “sugar-free” or “no sugar added” have carbohydrates in them. These foods may contain carbohydrate in the form of starch or sugar alcohols and will raise your blood sugar. Nutrition Facts The ingredients list Serving Size 1 bar will tell you which type of sweetener is Servings Per Container 12 in the food. Amount Per Serving Ingredients: whole milk, Look at the TOTAL Calories 90 condensed skim milk, CARBOHYDRATE. water, polydextrose, Total carbohydrate Total Fat 1.5g sorbitol, cocoa, milk includes starch, Saturated Fat 1g protein, aspartame, dietary fiber, sugars, Polyunsaturated Fat 0g vanilla and sugar alcohol. -

Optimization of Beer Brewing by Monitoring -Amylase

beverages Article Optimization of Beer Brewing by Monitoring α-Amylase and β-Amylase Activities during Mashing Raimon Parés Viader 1,*, Maiken Søe Holmstrøm Yde 1, Jens Winther Hartvig 1 , Marcus Pagenstecher 2 , Jacob Bille Carlsen 3, Troels Balmer Christensen 1 and Mogens Larsen Andersen 2 1 GlycoSpot ApS, 2860 Søborg, Denmark; [email protected] (M.S.H.Y.); [email protected] (J.W.H.); [email protected] (T.B.C.) 2 Department of Food Science, University of Copenhagen (KU FOOD), 1958 Frederiksberg, Denmark; [email protected] (M.P.); [email protected] (M.L.A.) 3 Bryghuset Møn, 4780 Stege, Denmark; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: (1) Background: In the current highly competitive brewing industry, most breweries may benefit from a reduction in mashing time. In this study, a novel enzymatic assay format was used to investigate the activities of α-amylase and β-amylase during different mashing profiles, with the aim to use it as a tool for optimizing the production time of an existing industrial mashing process; (2) Methods: Lab-scale mashings with eight different time-temperature programs and two different pilot brews were analyzed in terms of enzymatic activity, sugar composition, alcohol by volume in the final beer, FAN and others; (3) Results: A 20-min reduction (out of an original 73-min mashing program) was achieved by selecting a temperature profile which maintained a higher enzymatic activity than the original, without affecting the wort sugar composition and fermentability, or the Citation: Parés Viader, R.; Yde, M.S.H.; Hartvig, J.W.; Pagenstecher, ethanol concentration and foam stability of the final beer. -

Use of Aspergillus Oryzae During Sorghum Malting to Enhance Yield

Rubio‑Flores et al. Bioresour. Bioprocess. (2020) 7:40 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40643‑020‑00330‑w RESEARCH Open Access Use of Aspergillus oryzae during sorghum malting to enhance yield and quality of gluten‑free lager beers Monica Rubio‑Flores, Arnulfo Ricardo García‑Arellano , Esther Perez‑Carrillo and Sergio O. Serna‑Saldivar* Abstract Sorghum has been used for brewing European beers but its malt generally lower beer yields and alcohol contents. The aim of this research was to produce lager beers using worts from sorghum malted with and without Aspergillus oryzae inoculation. Worts adjusted to 15° Plato from the sorghum malt inoculated with 1% A. oryzae yielded 21.5% and 5% more volume compared to sorghum malt and barley malt worts, respectively. The main fermentable carbohydrate in all worts was maltose. Glucose was present in higher amounts in both sorghum worts compared to barley malt worts. Sorghum–A. oryzae beer had similar specifc gravity and alcohol compared to the barley malt beer. Sorghum–A. oryzae beer contained lower amounts of hydrogen sulfde, methanethiol, butanedione, and pentanedione compared to barley malt beer. Sorghum–A. oryzae lager beer had similar yield and alcohol content compared to the barley malt beer but difered in color, key volatiles and aromatic compounds. Keywords: Brewing, Gluten‑free, Lager beer, Aspergillus oryzae, Sorghum Introduction of many African people, and the industrialization of this Typically, barley has been the most relevant raw mate- kind of beer started more than 70 years ago (Bogdan and rial for beer production. Malt production is consid- Kordialik-Bogacka 2017; Odibo et al. -

Malt Beverage Formulation

Malt Beverage Formulation Presented by Michael Warren, Formulation Specialist Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau Specific Regulatory Authority for Malt Beverages • Alcohol Beverage Labeling Act of 1988 – 27 U.S.C. 213 et. Seq. – 27 CFR part 16 • Federal Alcohol Administration Act – 27 U.S.C. 205 – 27 CFR part 7 – Malt Beverages • Internal Revenue Code – 26 U.S.C. Chapter 51 – 27 CFR part 25 – Beer 2 How many formulas do we review per year? We received approximately 4246 malt beverage formula submissions in FY 2014 Of which, 45-50% are returned for correction!! 3 Formulation Team Mission • To properly Class and type the product to ensure the proper taxes are affixed. • To ensure all products are produced in accordance with all regulations making for an even “playing field” across the industry. • Ensure all products are made with safe ingredients and production processes by collaborating closely with the FDA. 4 Where can I go to find out if my Beer requires a Pre-Cola Evaluation? 5 Important Guidance Circulars • Industry Circular • TTB Ruling 2014-4 2007-4 6 Industry Circular 2007-4 • Is a road map to be used to determine if your product requires a Pre-Cola Evaluation 7 What types of products require Pre-Cola Evaluation? • Malt Beverage Specialties/Flavor ed Malt Beverages • Ice Beer • Alcohol Free Malt Beverages • IRC Beers 8 Malt Beverage Specialties • Malt beverage Specialty products are Beers that contain non exempted flavoring and coloring components and/or compounded flavors. 9 Release of TTB Ruling 2014-4 • Was released in response to the brewing industry submitting a request to exempt from formula requirements imposed by TTB regulations at 27 CFR 25.55, malt beverages made with honey, certain fruits, certain spices, and certain food ingredients. -

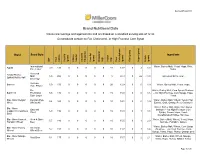

Brand Nutritional Data Values Are Average and Approximate and Are Based on a Standard Serving Size of 12 Oz

Revised 05/28/2019 Brand Nutritional Data Values are average and approximate and are based on a standard serving size of 12 oz. Our products contain no Fat, Cholesterol, or High Fructose Corn Syrup Brand Brand Style Ingredients ABV Total Calories Fat Total (grams) Calories Fat from Saturated Fat (grams) Trans Fat (grams) Cholesterol (mg) Sodium (mg) Total Carbohydrates (grams) Fiber (grams) Sugars (grams) Protein (grams) International Water, Barley Malt, Yeast, Hops, Rice, Aguila 3.9 126 0 0 0 0 0 10 13.7 0 2 1.0 Pale Lager Sugar Flavored Arnold Palmer Malt 5.0 206 0 0 0 0 0 5 28.3 0 26 < 1.0 Ingredient list to come Spiked Half & Half Beverage German- Barmen 5.0 156 0 0 0 0 0 20 12.9 0 0 1.9 Water, Barley Malt, Yeast, Hops Style Pilsner Pre- Water, Barley Malt, Corn Syrup (Dextrose Batch 19 Prohibition 5.5 174 0 0 0 0 0 15 15.0 0 0 1.6 – not High-Fructose Corn Syrup), Hops, Style Lager Yeast Blue Moon Belgian Belgian-Style Water, Barley Malt, Wheat, Yeast, Hop 5.4 168 0 0 0 0 0 10 14.1 0 0 1.9 White Wheat Ale Extract, Oats, Orange Peel, Coriander Water, Barley Malt, Oats, Corn Syrup Blue Moon Oatmeal (Maltose – not High-Fructose Corn Cappuccino Oatmeal 5.9 196 0 0 0 0 0 10 18.8 0 1 1.8 Stout Syrup), Cocoa, Hops, Yeast, Stout Decaffeinated Coffee, Sucrose Blue Moon Harvest Herb & Spice Water, Barley Malt, Wheat, Yeast, Hops, 5.7 180 0 0 0 0 0 10 15.5 0 1 2.0 Pumpkin Wheat Beer Sucrose, Pumpkin, Spices Water, Barley Malt, Wheat, Corn Syrup Blue Moon Honey American 5.2 153 0 0 0 0 0 10 11.7 0 3 1.4 (Dextrose – not High-Fructose Corn Wheat -

Carbohydrates Profile, Polyphenols Content and Antioxidative

molecules Article Carbohydrates Profile, Polyphenols Content and Antioxidative Properties of Beer Worts Produced with Different Dark Malts Varieties or Roasted Barley Grains Justyna G ˛asior 1,* , Joanna Kawa-Rygielska 1 and Alicja Z. Kucharska 2 1 Department of Fermentation and Cereals Technology, Faculty of Biotechnology and Food Science, Wroclaw University of Environmental and Life Sciences, Chełmo´nskiego37, 51-630 Wrocław, Poland; [email protected] 2 Department of Fruit, Vegetable and Plant Nutraceutical Technology, Faculty of Biotechnology and Food Science, Wroclaw University of Environmental and Life Sciences, Chełmo´nskiego37, 51-630 Wrocław, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-71-323-9417 Received: 29 July 2020; Accepted: 24 August 2020; Published: 26 August 2020 Abstract: The aim of this study was to assess the possibility of shaping properties of beers at the stage of brewing wort production with the use of various types of special malts (chocolate pale, chocolate dark, wheat chocolate, brown barley) and roasted barley grains. The carbohydrate profile, polyphenols content, antioxidant capacity, 5-hydroxymethylfurfural content, and the browning index level were analyzed. Statistical analysis showed significant differences in the values of the examined features between the samples. The sugars whose content was most affected by the addition of special malts were maltose and dextrins. The polyphenol content in worts with 10% of additive was 176.02–397.03 mg GAE/L, ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) 1.32–2.07 mmol TE/L, and capacity to reduction radical generated from 2,20-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic + acid) diammonium salt (ABTS• ) 1.46–2.70 mmol TE/L. -

A Study Assessing the Feasibility of Michigan Malt Houses

A Study Assessing the Feasibility of Michigan Malt Houses Prepared by William Knudson, PhD Product Center Food Ag Bio Michigan State University Date August 2014 Supported by: Malt House Feasibility Study Table of Contents I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 II. Economic Feasibility ......................................................................................................................... 2 III. Market Feasibility ............................................................................................................................ 3 IV. Technical Feasibility ......................................................................................................................... 5 V. Financial Feasibility .......................................................................................................................... 6 VI. Management Feasibility................................................................................................................... 9 VII. Summary ........................................................................................................................................ 10 VIII. References ..................................................................................................................................... 12 List of Tables Table 1: Income Statement for an Average Sized Commercial Malt House. ................................................ 7