The Court Scribe's Eikon Psyches a Note on Sima Qian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AUSTRO-LIBERTARIAN THEMES in EARLY CONFUCIANISM Roderick T

Journal of Libertarian Studies Volume 17, no. 3 (Summer 2003), pp. 35–62 2003 Ludwig von Mises Institute www.mises.org AUSTRO-LIBERTARIAN THEMES IN EARLY CONFUCIANISM Roderick T. Long* CONFUCIANISM: THE UNKNOWN IDEAL When scholars look for anticipations of classical liberal, Austrian, and libertarian ideas in early Chinese thought, attention usually focuses not on the Confucians, but on the Taoists, particularly on Laozi (Lao- tzu), reputed author of the Taoist classic Daodejing (Tao Te Ching).1 *Associate Professor of Philosophy at Auburn University. A version of this paper was presented at the 8th Austrian Scholars Conference at the Ludwig von Mises Institute, 15–16 March 2002. The author has benefited from com- ments and discussion on that occasion. A note on Chinese names and terms: There are several systems of ro- manization for Chinese names, the two most familiar being Pinyin and, in English-speaking countries, Wade-Giles, with the former now beginning to displace the latter. The two systems are different enough that terms in one system are often unrecognizable in the other. In two instances, in addition to the Wade-Giles and Pinyin transliteration, names are commonly Latinized: Confucius and Mencius. Throughout this essay I employ Pinyin. For the reader’s convenience, I also give the Wade-Giles equivalent (when it differs from the Pinyin) and the Latin in parentheses at the first occurrence of each term in text and footnotes. Terms in quotations and names of published articles and books are left as is, with the equivalents in parenthesis as appropriate. An appendix of transliterations is offered at the end of the article. -

The Rituals of Zhou in East Asian History

STATECRAFT AND CLASSICAL LEARNING: THE RITUALS OF ZHOU IN EAST ASIAN HISTORY Edited by Benjamin A. Elman and Martin Kern CHAPTER FOUR CENTERING THE REALM: WANG MANG, THE ZHOULI, AND EARLY CHINESE STATECRAFT Michael Puett, Harvard University In this chapter I address a basic problem: why would a text like the Rituals of Zhou (Zhouli !"), which purports to describe the adminis- trative structure of the Western Zhou ! dynasty (ca. 1050–771 BCE), come to be employed by Wang Mang #$ (45 BCE–23 CE) and, later, Wang Anshi #%& (1021–1086) in projects of strong state cen- tralization? Answering this question for the case of Wang Mang, how- ever, is no easy task. In contrast to what we have later for Wang Anshi, there are almost no sources to help us understand precisely how Wang Mang used, appropriated, and presented the Zhouli. We are told in the History of the [Western] Han (Hanshu '() that Wang Mang em- ployed the Zhouli, but we possess no commentaries on the text by ei- ther Wang Mang or one of his associates. In fact, we have no full commentary until Zheng Xuan )* (127–200 CE), who was far re- moved from the events of Wang Mang’s time and was concerned with different issues. Even the statements in the Hanshu about the uses of the Zhouli— referred to as the Offices of Zhou (Zhouguan !+) by Wang Mang— are brief. We are told that Wang Mang changed the ritual system of the time to follow that of the Zhouguan,1 that he used the Zhouguan for the taxation system,2 and that he used the Zhouguan, along with the “The Regulations of the King” (“Wangzhi” #,) chapter of the Records of Ritual (Liji "-), to organize state offices.3 I propose to tackle this problem in a way that is admittedly highly speculative. -

Rethinking the Relationship Between China and the West: a Multi- Dimensional Model of Cross-Cultural Research Focusing on Literary Adaptations

CULTURA CULTURA INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY OF CULTURE CULTURA AND AXIOLOGY Founded in 2004, Cultura. International Journal of Philosophy of 2012 Culture and Axiology is a semiannual peer-reviewed journal devo- 2 2012 Vol IX No 2 ted to philosophy of culture and the study of value. It aims to pro- mote the exploration of different values and cultural phenomena in regional and international contexts. The editorial board encourages OLOGY the submission of manuscripts based on original research that are I judged to make a novel and important contribution to understan- LOSOPHY OF I ding the values and cultural phenomena in the contempo rary world. CULTURE AND AX AND CULTURE ONAL JOURNAL OF PH I INTERNAT ISBN 978-3-631-62905-5 www.peterlang.de PETER LANG CULTURA 2012_262905_VOL_9_No2_GR_A5Br.indd 1 16.11.12 12:39:44 Uhr CULTURA CULTURA INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY OF CULTURE CULTURA AND AXIOLOGY Founded in 2004, Cultura. International Journal of Philosophy of 2014 Culture and Axiology is a semiannual peer-reviewed journal devo- 1 2014 Vol XI No 1 ted to philosophy of culture and the study of value. It aims to pro- mote the exploration of different values and cultural phenomena in regional and international contexts. The editorial board encourages the submission of manuscripts based on original research that are judged to make a novel and important contribution to understan- ding the values and cultural phenomena in the contempo rary world. CULTURE AND AXIOLOGY CULTURE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY INTERNATIONAL www.peterlang.com CULTURA 2014_265846_VOL_11_No1_GR_A5Br.indd.indd 1 14.05.14 17:43 Cultura. -

The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Wai Kit Wicky Tse University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tse, Wai Kit Wicky, "Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 589. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Abstract As a frontier region of the Qin-Han (221BCE-220CE) empire, the northwest was a new territory to the Chinese realm. Until the Later Han (25-220CE) times, some portions of the northwestern region had only been part of imperial soil for one hundred years. Its coalescence into the Chinese empire was a product of long-term expansion and conquest, which arguably defined the egionr 's military nature. Furthermore, in the harsh natural environment of the region, only tough people could survive, and unsurprisingly, the region fostered vigorous warriors. Mixed culture and multi-ethnicity featured prominently in this highly militarized frontier society, which contrasted sharply with the imperial center that promoted unified cultural values and stood in the way of a greater degree of transregional integration. As this project shows, it was the northwesterners who went through a process of political peripheralization during the Later Han times played a harbinger role of the disintegration of the empire and eventually led to the breakdown of the early imperial system in Chinese history. -

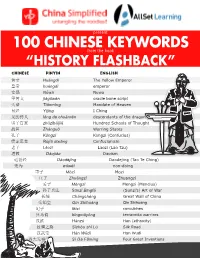

100 Chinese Keywords

present 100 CHINESE KEYWORDS from the book “HISTORY FLASHBACK” Chinese Pinyin English 黄帝 Huángdì The Yellow Emperor 皇帝 huángdì emperor 女娲 Nǚwā Nuwa 甲骨文 jiǎgǔwén oracle bone script 天命 Tiānmìng Mandate of Heaven 易经 Yìjīng I Ching 龙的传人 lóng de chuánrén descendants of the dragon 诸子百家 zhūzǐbǎijiā Hundred Schools of Thought 战国 Zhànguó Warring States 孔子 Kǒngzǐ Kongzi (Confucius) 儒家思想 Rújiā sīxiǎng Confucianism 老子 Lǎozǐ Laozi (Lao Tzu) 道教 Dàojiào Daoism 道德经 Dàodéjīng Daodejing (Tao Te Ching) 无为 wúwéi non-doing 墨子 Mòzǐ Mozi 庄子 Zhuāngzǐ Zhuangzi 孟子 Mèngzǐ Mengzi (Mencius) 孙子兵法 Sūnzǐ Bīngfǎ (Sunzi’s) Art of War 长城 Chángchéng Great Wall of China 秦始皇 Qín Shǐhuáng Qin Shihuang 妃子 fēizi concubines 兵马俑 bīngmǎyǒng terracotta warriors 汉族 Hànzú Han (ethnicity) 丝绸之路 Sīchóu zhī Lù Silk Road 汉武帝 Hàn Wǔdì Han Wudi 四大发明 Sì Dà Fāmíng Four Great Inventions Chinese Pinyin English 指南针 zhǐnánzhēn compass 火药 huǒyào gunpowder 造纸术 zàozhǐshù paper-making 印刷术 yìnshuāshù printing press 司马迁 Sīmǎ Qiān Sima Qian 史记 Shǐjì Records of the Grand Historian 太监 tàijiàn eunuch 三国 Sānguó Three Kingdoms (period) 竹林七贤 Zhúlín Qīxián Seven Bamboo Sages 花木兰 Huā Mùlán Hua Mulan 京杭大运河 Jīng-Háng Dàyùnhé Grand Canal 佛教 Fójiào Buddhism 武则天 Wǔ Zétiān Wu Zetian 四大美女 Sì Dà Měinǚ Four Great Beauties 唐诗 Tángshī Tang poetry 李白 Lǐ Bái Li Bai 杜甫 Dù Fǔ Du Fu Along the River During the Qingming 清明上河图 Qīngmíng Shàng Hé Tú Festival (painting) 科举 kējǔ imperial examination system 西藏 Xīzàng Tibet, Tibetan 书法 shūfǎ calligraphy 蒙古 Měnggǔ Mongolia, Mongolian 成吉思汗 Chéngjí Sīhán Genghis Khan 忽必烈 Hūbìliè Kublai -

Gender and the Poetry of Chen Yinke

Nostalgia and Resistance: Gender and the Poetry of Chen Yinke Wai-yee Li 李惠儀 Harvard University On June 2, 1927, the great scholar and poet Wang Guowei 王國維 (1877- 1927) drowned himself at Lake Kunming in the Imperial Summer Palace in Beijing. There was widespread perception at the time that Wang had committed suicide as a martyr for the fallen Qing dynasty, whose young deposed emperor had been Wang’s student. However, Chen Yinke 陳寅恪 (1890-1969), Wang’s friend and colleague at the Qinghua Research Institute of National Learning, offered a different interpretation in the preface to his “Elegy on Wang Guowei” 王觀堂先生輓詞并序: For today’s China is facing calamities and crises without precedents in its several thousand years of history. With these calamities and crises reaching ever more dire extremes, how can those whose very being represents a condensation and realization of the spirit of Chinese culture fail to identify with its fate and perish along with it? This was why Wang Guowei could not but die.1 Two years later, Chen elaborated upon the meaning of Wang’s death in a memorial stele: He died to make manifest his will to independence and freedom. This was neither about personal indebtedness and grudges, nor about the rise or fall of one ruling house… His writings may sink into oblivion; his teachings may yet be debated. But this spirit of independence and freedom of thought…will last for eternity with heaven and earth.2 Between these assertions from 1927 and 1929 is a rhetorical elision of potentially different positions. -

THE LAST YEARS 218–220 Liu Bei in Hanzhong 218–219 Guan Yu and Lü Meng 219 Posthumous Emperor 220 the Later History Of

CHAPTER TEN THE LAST YEARS 218–220 Liu Bei in Hanzhong 218–219 Guan Yu and Lü Meng 219 Posthumous emperor 220 The later history of Cao Wei Chronology 218–2201 218 spring: short-lived rebellion at Xu city Liu Bei sends an army into Hanzhong; driven back by Cao Hong summer: Wuhuan rebellion put down by Cao Cao’s son Zhang; Kebineng of the Xianbi surrenders winter: rebellion in Nanyang 219 spring: Nanyang rebellion put down by Cao Ren Liu Bei defeats Xiahou Yuan at Dingjun Mountain summer: Cao Cao withdraws from Hanzhong; Liu Bei presses east down the Han autumn: Liu Bei proclaims himself King of Hanzhong; Guan Yu attacks north in Jing province, besieges Cao Ren in Fan city rebellion of Wei Feng at Ye city winter: Guan Yu defeated at Fan; Lü Meng seizes Jing province for Sun Quan and destroys Guan Yu 220 spring [15 March]: Cao Cao dies at Luoyang; Cao Pi succeeds him as King of Wei winter [11 December]: Cao Pi takes the imperial title; Cao Cao is given posthumous honour as Martial Emperor of Wei [Wei Wudi] * * * * * 1 The major source for Cao Cao’s activities from 218 to 220 is SGZ 1:50–53. They are presented in chronicle order by ZZTJ 68:2154–74 and 69:2175; deC, Establish Peace, 508–560. 424 chapter ten Chronology from 220 222 Lu Xun defeats the revenge attack of Liu Bei against Sun Quan 226 death of Cao Pi, succeeded by his son Cao Rui 238 death of Cao Rui, succeeded by Cao Fang under the regency of Cao Shuang 249 Sima Yi destroys Cao Shuang and seizes power in the state of Wei for his family 254 Sima Shi deposes Cao Fang, replacing him with Cao Mao 255 Sima Shi succeeded by Sima Zhao 260 Cao Mao killed in a coup d’état; replaced by Cao Huan 264 conquest of Shu-Han 266 Sima Yan takes title as Emperor of Jin 280 conquest of Wu by Jin Liu Bei in Hanzhong 218–219 Even while Cao Cao steadily developed his position with honours, titles and insignia, he continued to proclaim his loyalty to Han and to represent himself as a servant—albeit a most successful and distin- guished one—of the established dynasty. -

Chinese Literature in the Second Half of a Modern Century: a Critical Survey

CHINESE LITERATURE IN THE SECOND HALF OF A MODERN CENTURY A CRITICAL SURVEY Edited by PANG-YUAN CHI and DAVID DER-WEI WANG INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS • BLOOMINGTON AND INDIANAPOLIS William Tay’s “Colonialism, the Cold War Era, and Marginal Space: The Existential Condition of Five Decades of Hong Kong Literature,” Li Tuo’s “Resistance to Modernity: Reflections on Mainland Chinese Literary Criticism in the 1980s,” and Michelle Yeh’s “Death of the Poet: Poetry and Society in Contemporary China and Taiwan” first ap- peared in the special issue “Contemporary Chinese Literature: Crossing the Bound- aries” (edited by Yvonne Chang) of Literature East and West (1995). Jeffrey Kinkley’s “A Bibliographic Survey of Publications on Chinese Literature in Translation from 1949 to 1999” first appeared in Choice (April 1994; copyright by the American Library Associ- ation). All of the essays have been revised for this volume. This book is a publication of Indiana University Press 601 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA http://www.indiana.edu/~iupress Telephone orders 800-842-6796 Fax orders 812-855-7931 Orders by e-mail [email protected] © 2000 by David D. W. Wang All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses’ Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. -

Weaponry During the Period of Disunity in Imperial China with a Focus on the Dao

Weaponry During the Period of Disunity in Imperial China With a focus on the Dao An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty Of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE By: Bryan Benson Ryan Coran Alberto Ramirez Date: 04/27/2017 Submitted to: Professor Diana A. Lados Mr. Tom H. Thomsen 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 List of Figures 4 Individual Participation 7 Authorship 8 1. Abstract 10 2. Introduction 11 3. Historical Background 12 3.1 Fall of Han dynasty/ Formation of the Three Kingdoms 12 3.2 Wu 13 3.3 Shu 14 3.4 Wei 16 3.5 Warfare and Relations between the Three Kingdoms 17 3.5.1 Wu and the South 17 3.5.2 Shu-Han 17 3.5.3 Wei and the Sima family 18 3.6 Weaponry: 18 3.6.1 Four traditional weapons (Qiang, Jian, Gun, Dao) 18 3.6.1.1 The Gun 18 3.6.1.2 The Qiang 19 3.6.1.3 The Jian 20 3.6.1.4 The Dao 21 3.7 Rise of the Empire of Western Jin 22 3.7.1 The Beginning of the Western Jin Empire 22 3.7.2 The Reign of Empress Jia 23 3.7.3 The End of the Western Jin Empire 23 3.7.4 Military Structure in the Western Jin 24 3.8 Period of Disunity 24 4. Materials and Manufacturing During the Period of Disunity 25 2 Table of Contents (Cont.) 4.1 Manufacturing of the Dao During the Han Dynasty 25 4.2 Manufacturing of the Dao During the Period of Disunity 26 5. -

Early Chinese Diplomacy: Realpolitik Versus the So-Called Tributary System

realpolitik versus tributary system armin selbitschka Early Chinese Diplomacy: Realpolitik versus the So-called Tributary System SETTING THE STAGE: THE TRIBUTARY SYSTEM AND EARLY CHINESE DIPLOMACY hen dealing with early-imperial diplomacy in China, it is still next W to impossible to escape the concept of the so-called “tributary system,” a term coined in 1941 by John K. Fairbank and S. Y. Teng in their article “On the Ch’ing Tributary System.”1 One year later, John Fairbank elaborated on the subject in the much shorter paper “Tribu- tary Trade and China’s Relations with the West.”2 Although only the second work touches briefly upon China’s early dealings with foreign entities, both studies proved to be highly influential for Yü Ying-shih’s Trade and Expansion in Han China: A Study in the Structure of Sino-Barbarian Economic Relations published twenty-six years later.3 In particular the phrasing of the latter two titles suffices to demonstrate the three au- thors’ main points: foreigners were primarily motivated by economic I am grateful to Michael Loewe, Hans van Ess, Maria Khayutina, Kathrin Messing, John Kiesch nick, Howard L. Goodman, and two anonymous Asia Major reviewers for valuable suggestions to improve earlier drafts of this paper. Any remaining mistakes are, of course, my own responsibility. 1 J. K. Fairbank and S. Y. Teng, “On the Ch’ing Tributary System,” H JAS 6.2 (1941), pp. 135–246. 2 J. K. Fairbank in FEQ 1.2 (1942), pp. 129–49. 3 Yü Ying-shih, Trade and Expansion in Han China: A Study in the Structure of Sino-barbarian Economic Relations (Berkeley and Los Angeles: U. -

Title Criticism and Society: the Birth of the Modern Critical Subject in China Author(S)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by HKU Scholars Hub Criticism and society: The birth of the modern critical subject in Title China Author(s) Tong, QS; Zhou, X Citation Boundary 2, 2002, v. 29 n. 1, p. 153-176 Issued Date 2002 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10722/42588 Rights Creative Commons: Attribution 3.0 Hong Kong License Criticism and Society: The Birth of the Modern Critical Subject in China Q. S. Tong and Xiaoyi Zhou Over the past ten years or so, there have been repeated calls in China for the creation and establishment of a system of critical theory that bears distinct indigenous features, a system that is ‘‘national,’’ or ‘‘Chinese,’’ and that will therefore be different, both formally and substantively, from those imported critical approaches and theoretical formulations.1 However, these We thank Paul Bové, Jonathan Arac, and the anonymous readers of the boundary 2 edi- torial collective for their comments and suggestions. We also owe Meg Havran a note of thanks for editing the manuscript. Translations from Chinese sources, unless otherwise noted, are ours. 1. Articulations of the desire for an indigenous critical theory are copious. They started to be heard in the late 1980s and became a visible critical movement in the mid-1990s. In the first issue of Wenxue pinglun (Literary review) in 1997, the leading critical journal in China, for example, an entire section is devoted to the issue of how to modernize classi- cal Chinese critical theory. The following list of titles, albeit short and far from complete, is perhaps sufficient to show the solemnity and intensity of the issue for Chinese literary intellectuals: Cao Shunqing, ‘‘Ershiyi shiji zhongguo wenhua fazhanzhanlue yu chongjian zhongguo wenlun huayu’’ (Strategies for Chinese cultural developments in the twenty-first century and reconstruction of the discourse of Chinese literary theory), Dongfang cong- kan (Oriental series), no. -

MCM Problem a Contest Results

2021 Mathematical Contest in Modeling® Press Release—April 23, 2021 COMAP is pleased to announce the results of the 37th annual advantages and disadvantages for fungi species and combinations of Mathematical Contest in Modeling (MCM). This year, 10,053 teams species like to persist is various environments. representing institutions from fifteen countries/regions participated in the contest. Seventeen teams from the following institutions were The B problem used the scenario of the 2019-2020 fire season in designated as OUTSTANDING WINNERS: Australia, which saw devastating wildfires in every state, to consider the use of drones in firefighting. Teams learned of the capabilities of Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China (3) two types of drones, surveillance and situational awareness drones and (2100454 SIAM Award & COMAP Scholarship Award) hovering drones that can carry repeaters (to extend radio range), and Beijing Institute of Technology, China (Ben Fusaro Award) then created a model to determine the optimal numbers and mix of Nanjing University of Posts & Telecommunications, China these two types of drones. Teams addressed adaptation of their model (Frank Giordano Award & SIAM Award) to the changing likelihood of extreme fire events over the next decade, Jiangnan University, China as well as to equipment cost increases. Teams also developed a model Xi'an Jiaotong University, China (AMS Award) to optimize locations of hovering drones for fires of differing sizes on Xidian University, Shannxi, China differing terrain. Beijing Jiaotong University, China (ASA Award) University of Colorado Boulder, CO, USA The C problem investigated the discovery and sightings of Vespa (MAA Award, SIAM Award & COMAP Scholarship Award) mandarina (also known as the Asian giant hornet) in the State of University of Oxford, United Kingdom Washington.