Life and Teachings of Confucius

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AUSTRO-LIBERTARIAN THEMES in EARLY CONFUCIANISM Roderick T

Journal of Libertarian Studies Volume 17, no. 3 (Summer 2003), pp. 35–62 2003 Ludwig von Mises Institute www.mises.org AUSTRO-LIBERTARIAN THEMES IN EARLY CONFUCIANISM Roderick T. Long* CONFUCIANISM: THE UNKNOWN IDEAL When scholars look for anticipations of classical liberal, Austrian, and libertarian ideas in early Chinese thought, attention usually focuses not on the Confucians, but on the Taoists, particularly on Laozi (Lao- tzu), reputed author of the Taoist classic Daodejing (Tao Te Ching).1 *Associate Professor of Philosophy at Auburn University. A version of this paper was presented at the 8th Austrian Scholars Conference at the Ludwig von Mises Institute, 15–16 March 2002. The author has benefited from com- ments and discussion on that occasion. A note on Chinese names and terms: There are several systems of ro- manization for Chinese names, the two most familiar being Pinyin and, in English-speaking countries, Wade-Giles, with the former now beginning to displace the latter. The two systems are different enough that terms in one system are often unrecognizable in the other. In two instances, in addition to the Wade-Giles and Pinyin transliteration, names are commonly Latinized: Confucius and Mencius. Throughout this essay I employ Pinyin. For the reader’s convenience, I also give the Wade-Giles equivalent (when it differs from the Pinyin) and the Latin in parentheses at the first occurrence of each term in text and footnotes. Terms in quotations and names of published articles and books are left as is, with the equivalents in parenthesis as appropriate. An appendix of transliterations is offered at the end of the article. -

Engineers' Moral Responsibility: a Confucian Perspective

Science and Engineering Ethics https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-019-00093-4 ORIGINAL RESEARCH/SCHOLARSHIP Engineers’ Moral Responsibility: A Confucian Perspective Shan Jing1,2 · Neelke Doorn2 Received: 13 April 2018 / Accepted: 31 January 2019 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract Moral responsibility is one of the core concepts in engineering ethics and conse- quently in most engineering ethics education. Yet, despite a growing awareness that engineers should be trained to become more sensitive to cultural diferences, most engineering ethics education is still based on Western approaches. In this article, we discuss the notion of responsibility in Confucianism and explore what a Confu- cian perspective could add to the existing engineering ethics literature. To do so, we analyse the Citicorp case, a widely discussed case in the existing engineering ethics literature, from a Confucian perspective. Our comparison suggests the fol- lowing. When compared to virtue ethics based on Aristotle, Confucianism focuses primarily on ethical virtues; there is no explicit reference to intellectual virtues. An important diference between Confucianism and most western approaches is that Confucianism does not defne clear boundaries of where a person’s responsibility end. It also suggests that the gap between Western and at least one Eastern approach, namely Confucianism, can be bridged. Although there are diferences, the Confu- cian view and a virtue-based Western view on moral responsibility have much in common, which allows for a promising base for culturally inclusive ethics education for engineers. Keywords Responsibility · Confucianism · Virtues · Inclusive education · Citicorp Building * Neelke Doorn [email protected] Shan Jing [email protected] 1 School of Humanities, Southeast University, Nanjing 211189, Jiangsu Province, People’s Republic of China 2 Department of Technology, Policy and Management, Delft University of Technology, P.O. -

The Educational Thought of Confucius

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1980 The Educational Thought of Confucius Helena Wan Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Wan, Helena, "The Educational Thought of Confucius" (1980). Dissertations. 1875. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1875 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1980 Helena Wan THE EDUCATIONAL THOUGHT OF CONFUCIUS by Helena Wan A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 1980 Helena Wan Loyola University of Chicago THE EDUCATIONAL THOUGHT OF CONFUCIUS The purpose of this study is to investigate the humanistic educational ideas of Confucius as they truly were, and to examine their role in the history of tradi- tional Chinese education. It is the contention of this study that the process of transformation from idea into practice has led to mutilation, adaptation or deliberate reinterpretation of the original set of ideas. The ex ample of the evolution of the humanistic educational ideas of Confucius into a system of education seems to support this contention. It is hoped that this study will help separate that which is genuinely Confucius' from that which tradition has attributed to him; and to understand how this has happened and what consequences have resulted. -

The Analects of Confucius

The analecTs of confucius An Online Teaching Translation 2015 (Version 2.21) R. Eno © 2003, 2012, 2015 Robert Eno This online translation is made freely available for use in not for profit educational settings and for personal use. For other purposes, apart from fair use, copyright is not waived. Open access to this translation is provided, without charge, at http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23420 Also available as open access translations of the Four Books Mencius: An Online Teaching Translation http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23421 Mencius: Translation, Notes, and Commentary http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23423 The Great Learning and The Doctrine of the Mean: An Online Teaching Translation http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23422 The Great Learning and The Doctrine of the Mean: Translation, Notes, and Commentary http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23424 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION i MAPS x BOOK I 1 BOOK II 5 BOOK III 9 BOOK IV 14 BOOK V 18 BOOK VI 24 BOOK VII 30 BOOK VIII 36 BOOK IX 40 BOOK X 46 BOOK XI 52 BOOK XII 59 BOOK XIII 66 BOOK XIV 73 BOOK XV 82 BOOK XVI 89 BOOK XVII 94 BOOK XVIII 100 BOOK XIX 104 BOOK XX 109 Appendix 1: Major Disciples 112 Appendix 2: Glossary 116 Appendix 3: Analysis of Book VIII 122 Appendix 4: Manuscript Evidence 131 About the title page The title page illustration reproduces a leaf from a medieval hand copy of the Analects, dated 890 CE, recovered from an archaeological dig at Dunhuang, in the Western desert regions of China. The manuscript has been determined to be a school boy’s hand copy, complete with errors, and it reproduces not only the text (which appears in large characters), but also an early commentary (small, double-column characters). -

The Rituals of Zhou in East Asian History

STATECRAFT AND CLASSICAL LEARNING: THE RITUALS OF ZHOU IN EAST ASIAN HISTORY Edited by Benjamin A. Elman and Martin Kern CHAPTER FOUR CENTERING THE REALM: WANG MANG, THE ZHOULI, AND EARLY CHINESE STATECRAFT Michael Puett, Harvard University In this chapter I address a basic problem: why would a text like the Rituals of Zhou (Zhouli !"), which purports to describe the adminis- trative structure of the Western Zhou ! dynasty (ca. 1050–771 BCE), come to be employed by Wang Mang #$ (45 BCE–23 CE) and, later, Wang Anshi #%& (1021–1086) in projects of strong state cen- tralization? Answering this question for the case of Wang Mang, how- ever, is no easy task. In contrast to what we have later for Wang Anshi, there are almost no sources to help us understand precisely how Wang Mang used, appropriated, and presented the Zhouli. We are told in the History of the [Western] Han (Hanshu '() that Wang Mang em- ployed the Zhouli, but we possess no commentaries on the text by ei- ther Wang Mang or one of his associates. In fact, we have no full commentary until Zheng Xuan )* (127–200 CE), who was far re- moved from the events of Wang Mang’s time and was concerned with different issues. Even the statements in the Hanshu about the uses of the Zhouli— referred to as the Offices of Zhou (Zhouguan !+) by Wang Mang— are brief. We are told that Wang Mang changed the ritual system of the time to follow that of the Zhouguan,1 that he used the Zhouguan for the taxation system,2 and that he used the Zhouguan, along with the “The Regulations of the King” (“Wangzhi” #,) chapter of the Records of Ritual (Liji "-), to organize state offices.3 I propose to tackle this problem in a way that is admittedly highly speculative. -

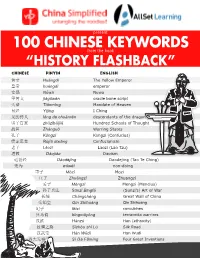

100 Chinese Keywords

present 100 CHINESE KEYWORDS from the book “HISTORY FLASHBACK” Chinese Pinyin English 黄帝 Huángdì The Yellow Emperor 皇帝 huángdì emperor 女娲 Nǚwā Nuwa 甲骨文 jiǎgǔwén oracle bone script 天命 Tiānmìng Mandate of Heaven 易经 Yìjīng I Ching 龙的传人 lóng de chuánrén descendants of the dragon 诸子百家 zhūzǐbǎijiā Hundred Schools of Thought 战国 Zhànguó Warring States 孔子 Kǒngzǐ Kongzi (Confucius) 儒家思想 Rújiā sīxiǎng Confucianism 老子 Lǎozǐ Laozi (Lao Tzu) 道教 Dàojiào Daoism 道德经 Dàodéjīng Daodejing (Tao Te Ching) 无为 wúwéi non-doing 墨子 Mòzǐ Mozi 庄子 Zhuāngzǐ Zhuangzi 孟子 Mèngzǐ Mengzi (Mencius) 孙子兵法 Sūnzǐ Bīngfǎ (Sunzi’s) Art of War 长城 Chángchéng Great Wall of China 秦始皇 Qín Shǐhuáng Qin Shihuang 妃子 fēizi concubines 兵马俑 bīngmǎyǒng terracotta warriors 汉族 Hànzú Han (ethnicity) 丝绸之路 Sīchóu zhī Lù Silk Road 汉武帝 Hàn Wǔdì Han Wudi 四大发明 Sì Dà Fāmíng Four Great Inventions Chinese Pinyin English 指南针 zhǐnánzhēn compass 火药 huǒyào gunpowder 造纸术 zàozhǐshù paper-making 印刷术 yìnshuāshù printing press 司马迁 Sīmǎ Qiān Sima Qian 史记 Shǐjì Records of the Grand Historian 太监 tàijiàn eunuch 三国 Sānguó Three Kingdoms (period) 竹林七贤 Zhúlín Qīxián Seven Bamboo Sages 花木兰 Huā Mùlán Hua Mulan 京杭大运河 Jīng-Háng Dàyùnhé Grand Canal 佛教 Fójiào Buddhism 武则天 Wǔ Zétiān Wu Zetian 四大美女 Sì Dà Měinǚ Four Great Beauties 唐诗 Tángshī Tang poetry 李白 Lǐ Bái Li Bai 杜甫 Dù Fǔ Du Fu Along the River During the Qingming 清明上河图 Qīngmíng Shàng Hé Tú Festival (painting) 科举 kējǔ imperial examination system 西藏 Xīzàng Tibet, Tibetan 书法 shūfǎ calligraphy 蒙古 Měnggǔ Mongolia, Mongolian 成吉思汗 Chéngjí Sīhán Genghis Khan 忽必烈 Hūbìliè Kublai -

THE LAST YEARS 218–220 Liu Bei in Hanzhong 218–219 Guan Yu and Lü Meng 219 Posthumous Emperor 220 the Later History Of

CHAPTER TEN THE LAST YEARS 218–220 Liu Bei in Hanzhong 218–219 Guan Yu and Lü Meng 219 Posthumous emperor 220 The later history of Cao Wei Chronology 218–2201 218 spring: short-lived rebellion at Xu city Liu Bei sends an army into Hanzhong; driven back by Cao Hong summer: Wuhuan rebellion put down by Cao Cao’s son Zhang; Kebineng of the Xianbi surrenders winter: rebellion in Nanyang 219 spring: Nanyang rebellion put down by Cao Ren Liu Bei defeats Xiahou Yuan at Dingjun Mountain summer: Cao Cao withdraws from Hanzhong; Liu Bei presses east down the Han autumn: Liu Bei proclaims himself King of Hanzhong; Guan Yu attacks north in Jing province, besieges Cao Ren in Fan city rebellion of Wei Feng at Ye city winter: Guan Yu defeated at Fan; Lü Meng seizes Jing province for Sun Quan and destroys Guan Yu 220 spring [15 March]: Cao Cao dies at Luoyang; Cao Pi succeeds him as King of Wei winter [11 December]: Cao Pi takes the imperial title; Cao Cao is given posthumous honour as Martial Emperor of Wei [Wei Wudi] * * * * * 1 The major source for Cao Cao’s activities from 218 to 220 is SGZ 1:50–53. They are presented in chronicle order by ZZTJ 68:2154–74 and 69:2175; deC, Establish Peace, 508–560. 424 chapter ten Chronology from 220 222 Lu Xun defeats the revenge attack of Liu Bei against Sun Quan 226 death of Cao Pi, succeeded by his son Cao Rui 238 death of Cao Rui, succeeded by Cao Fang under the regency of Cao Shuang 249 Sima Yi destroys Cao Shuang and seizes power in the state of Wei for his family 254 Sima Shi deposes Cao Fang, replacing him with Cao Mao 255 Sima Shi succeeded by Sima Zhao 260 Cao Mao killed in a coup d’état; replaced by Cao Huan 264 conquest of Shu-Han 266 Sima Yan takes title as Emperor of Jin 280 conquest of Wu by Jin Liu Bei in Hanzhong 218–219 Even while Cao Cao steadily developed his position with honours, titles and insignia, he continued to proclaim his loyalty to Han and to represent himself as a servant—albeit a most successful and distin- guished one—of the established dynasty. -

Weaponry During the Period of Disunity in Imperial China with a Focus on the Dao

Weaponry During the Period of Disunity in Imperial China With a focus on the Dao An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty Of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE By: Bryan Benson Ryan Coran Alberto Ramirez Date: 04/27/2017 Submitted to: Professor Diana A. Lados Mr. Tom H. Thomsen 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 List of Figures 4 Individual Participation 7 Authorship 8 1. Abstract 10 2. Introduction 11 3. Historical Background 12 3.1 Fall of Han dynasty/ Formation of the Three Kingdoms 12 3.2 Wu 13 3.3 Shu 14 3.4 Wei 16 3.5 Warfare and Relations between the Three Kingdoms 17 3.5.1 Wu and the South 17 3.5.2 Shu-Han 17 3.5.3 Wei and the Sima family 18 3.6 Weaponry: 18 3.6.1 Four traditional weapons (Qiang, Jian, Gun, Dao) 18 3.6.1.1 The Gun 18 3.6.1.2 The Qiang 19 3.6.1.3 The Jian 20 3.6.1.4 The Dao 21 3.7 Rise of the Empire of Western Jin 22 3.7.1 The Beginning of the Western Jin Empire 22 3.7.2 The Reign of Empress Jia 23 3.7.3 The End of the Western Jin Empire 23 3.7.4 Military Structure in the Western Jin 24 3.8 Period of Disunity 24 4. Materials and Manufacturing During the Period of Disunity 25 2 Table of Contents (Cont.) 4.1 Manufacturing of the Dao During the Han Dynasty 25 4.2 Manufacturing of the Dao During the Period of Disunity 26 5. -

The Ghosts of Monotheism: Heaven, Fortune, and Universalism in Early Chinese and Greco-Roman Historiography

The Ghosts of Monotheism: Heaven, Fortune, and Universalism in Early Chinese and Greco-Roman Historiography FILIPPO MARSILI Saint Louis University [email protected] Abstract: This essay analyzes the creation of the empires of Rome over the Medi- terranean and of the Han dynasty over the Central Plains between the third and the second centuries BCE. It focuses on the historiographical oeuvres of Polybius and Sima Qian, as the two men tried to make sense of the unification of the world as they knew it. The essay does away with the subsequent methodological and conceptual biases introduced by interpreters who approached the material from the vantage point of Abrahamic religions, according to which transcendent per- sonal entities could favor the foundation of unitary political and moral systems. By considering the impact of the different contexts and of the two authors’ sub- jective experiences, the essay tries to ascertain the extent to which Polybius and Sima Qian tended to associate unified rule with the triumph of universal values and the establishment of superior, divine justice. All profound changes in consciousness, by their very nature, bring with them characteristic amnesias. Out of such oblivions, in specific historical circumstances, spring narratives.—Benedict Anderson1 The nation as the subject of History is never able to completely bridge the aporia between the past and the present.—Prasenjit Duara2 Any structure is the ingenuous re-proposition of a hidden god; any systemic approach might actually constitute a crypto-theology.—Benedetto Croce3 Introduction: Monotheism, Systemic Unities, and Ethnocentrism Scholars who engage in comparisons are often wary of the ethnocentric biases that lurk behind their endeavors. -

The Relevance of Confucian Philosophy to Modern Concepts of Leadership and Followership Sujeeta Dhakhwa University of North Florida

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNF Digital Commons University of North Florida UNF Digital Commons All Volumes (2001-2008) The sprO ey Journal of Ideas and Inquiry 2008 The Relevance of Confucian Philosophy to Modern Concepts of Leadership and Followership Sujeeta Dhakhwa University of North Florida Stacey Enriquez University of North Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unf.edu/ojii_volumes Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Suggested Citation Dhakhwa, Sujeeta and Enriquez, Stacey, "The Relevance of Confucian Philosophy to Modern Concepts of Leadership and Followership" (2008). All Volumes (2001-2008). 5. http://digitalcommons.unf.edu/ojii_volumes/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The sprO ey Journal of Ideas and Inquiry at UNF Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Volumes (2001-2008) by an authorized administrator of UNF Digital Commons. For more information, please contact Digital Projects. © 2008 All Rights Reserved The Relevance of Confucian Philosophy to Modern Concepts of Leadership and Followership Sujeeta Dhakhwa and Stacey Enriquez Faculty Sponsor: William Ahrens Abstract The purpose of this paper is to discuss Confucian philosophy and compare its relevance to modern concepts of leadership and followership. It will demonstrate that both exemplify the same ideology, though separated by centuries of history. The paper first introduces the reader to the history of Chinese government and the life of Confucius as a teacher. Then it will expand on the importance of understanding his philosophy on leadership and followership as well as its impact on China’s political and cultural development. -

A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture

A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture Edited by Antje Richter LEIDEN | BOSTON For use by the Author only | © 2015 Koninklijke Brill NV Contents Acknowledgements ix List of Illustrations xi Abbreviations xiii About the Contributors xiv Introduction: The Study of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture 1 Antje Richter PART 1 Material Aspects of Chinese Letter Writing Culture 1 Reconstructing the Postal Relay System of the Han Period 17 Y. Edmund Lien 2 Letters as Calligraphy Exemplars: The Long and Eventful Life of Yan Zhenqing’s (709–785) Imperial Commissioner Liu Letter 53 Amy McNair 3 Chinese Decorated Letter Papers 97 Suzanne E. Wright 4 Material and Symbolic Economies: Letters and Gifts in Early Medieval China 135 Xiaofei Tian PART 2 Contemplating the Genre 5 Letters in the Wen xuan 189 David R. Knechtges 6 Between Letter and Testament: Letters of Familial Admonition in Han and Six Dynasties China 239 Antje Richter For use by the Author only | © 2015 Koninklijke Brill NV vi Contents 7 The Space of Separation: The Early Medieval Tradition of Four-Syllable “Presentation and Response” Poetry 276 Zeb Raft 8 Letters and Memorials in the Early Third Century: The Case of Cao Zhi 307 Robert Joe Cutter 9 Liu Xie’s Institutional Mind: Letters, Administrative Documents, and Political Imagination in Fifth- and Sixth-Century China 331 Pablo Ariel Blitstein 10 Bureaucratic Influences on Letters in Middle Period China: Observations from Manuscript Letters and Literati Discourse 363 Lik Hang Tsui PART 3 Diversity of Content and Style section 1 Informal Letters 11 Private Letter Manuscripts from Early Imperial China 403 Enno Giele 12 Su Shi’s Informal Letters in Literature and Life 475 Ronald Egan 13 The Letter as Artifact of Sentiment and Legal Evidence 508 Janet Theiss 14 Infijinite Variations of Writing and Desire: Love Letters in China and Europe 546 Bonnie S. -

Teaching Confucianism Edited by Jeffrey L

RESOURCES BOOKREVIEWESSAYS TEACHING CONFUCIANISM EDITED BY JEFFREY L. RICHEY OXFORD:OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS, 2008 224 PAGES, ISBN: 978-0195311600, PAPERBACK Reviewed by Thomas P.Dolan hile any scholar or teacher of Chinese culture and philos- ophy is familiar with the classic works of literature of two Wmillennia ago (Yijing, The Analects of Confucius, the Art of War and many others), these are often presented to students without the contexts in which they were developed. Doing so is like trying to ex- plain Christianity to someone without reference to Judaism or the Roman occupation of Judea, or like trying to explain Socialism with- out referring to Marx or Lenin. Jeffrey Richey’s Teaching Confucianism offers us the opportunity to provide the proper setting for discussions of Confucian beliefs, ethics, and behavior through a collection of teach- ing commentaries suitable for a variety of audiences. Richey and John Berthong begin by separating the study of Con- fucianism into six “epochs,”from the time of Confucius up to the twen- tieth century. Over time, Confucian ideas have been applied to different situations for different purposes, and the essays in this text reflect those differences. Mark Csikszentmihalyi’s “The Social and Religious Context of Early Confucian Practice” fleshes out the beginner’s exposure to the rituals addressed in Analects. By giving a more detailed explanation of the imagery used in some of the classic works mentioned in post-Con- fucian writings, this essay explains that the disciples of Confucius would have been familiar with such works as the Classic of Odes (Book of Odes) and Records of Ritual.