The Great Streetcar Conspiracy by Randal O’Toole

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History and Politics of Transportation in the United States

History and Politics of Transportation in the United States Transportation has always shaped development. It has been a major factor in the growth of the United States from the earliest days of settlement. The location and the success of a city depended on its proximity to the various transportation systems of the era. In each new phase, cooperation between government and private entrepreneurs was always the key to the success of the enterprise. In many cases, one mode was favored over another with politics and even corruption playing a major role in determining the choices of modes and the shape of development patterns. This paper will provide background materials to help instructors understand the basic historical and political factors behind the growth of transportation systems in the United States. Supplemental fact sheets will provide specific information and quotes and statistics on economic, environmental, health and safety factors related to transportation. WATER TRANSPORTATION In the early days of the United States, as the country grew in size and population, the need for an efficient transportation system linking the coastal cities with the rich agricultural interior countryside became more and more pressing. The first significant progress in national transportation was river steamboat navigation, pioneered by Fulton and Livingston on the Hudson and Henry Miller Shreve on the Mississippi. Steam navigation cut the time of a journey between New York and Albany by two thirds. The second major improvement was canal construction. Prominent people in New York who supported the building of the Erie Canal included Stephen Van Rensselaer III. The Erie Canal, which linked the Hudson River to Lake Erie, was opened in 1825 and its impact on the economic development of New York City and the hin- terland was huge. -

City of Milwaukee, Wis. Environmental Assessment October 2011

City of Milwaukee, Wis. Environmental Assessment October 2011 Prepared by the City of Milwaukee in cooperation with the Federal Transit Administration (THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK) Milwaukee Streetcar Environmental Assessment ii October 2011 RESPONSIBLE AGENCIES Lead Agency: Federal Transit Administration Project Sponsors: City of Milwaukee WHERE TO FIND COPIES OF THIS DOCUMENT A hard copy of the document is available for public inspection at the Federal Transit Administration field office at the following location: Federal Transit Administration Region V 200 West Adams Street, Suite 320 Chicago, Illinois 60606 Hard copies of the document will also be available at the following locations: Milwaukee Public Library – Central Milwaukee Public Library – Center Street 814 W. Wisconsin Avenue 2727 W. Fond du Lac Avenue Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53233 Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53210 Milwaukee Public Library – Forest Home Milwaukee Department of City Development 1432 W. Forest Home Avenue 809 Broadway, 1st Floor Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53204 Milwaukee, WI 53202 Legislative Reference Bureau, Milwaukee City Hall City Hall, Room B-11 200 East Wells Street Milwaukee, WI 53202 To view an electronic copy of this document, please visit the project Web site at www.themilwaukeestreetcar.com. CONTACT INFORMATION For additional information concerning this document please contact our public involvement coordinator who can direct your questions and comments to the appropriate person: Lois Kimmelman, Environmental Protection Specialist Federal Transit Administration Region 5 200 West Adams St., Suite 320 Chicago, IL 60606 Kristine Martinsek, Milwaukee Streetcar Public Involvement Coordinator Martinsek and Associates 1325 E. Potter Avenue Milwaukee, WI 53207 Milwaukee Streetcar Environmental Assessment iii October 2011 ABSTRACT The proposed Milwaukee Streetcar project would establish a starter streetcar system in and around downtown Milwaukee connecting workers, visitors and residents to key destinations and attractions. -

Metrorail/Coconut Grove Connection Study Phase II Technical

METRORAILICOCONUT GROVE CONNECTION STUDY DRAFT BACKGROUND RESEARCH Technical Memorandum Number 2 & TECHNICAL DATA DEVELOPMENT Technical Memorandum Number 3 Prepared for Prepared by IIStB Reynolds, Smith and Hills, Inc. 6161 Blue Lagoon Drive, Suite 200 Miami, Florida 33126 December 2004 METRORAIUCOCONUT GROVE CONNECTION STUDY DRAFT BACKGROUND RESEARCH Technical Memorandum Number 2 Prepared for Prepared by BS'R Reynolds, Smith and Hills, Inc. 6161 Blue Lagoon Drive, Suite 200 Miami, Florida 33126 December 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 1 2.0 STUDY DESCRiPTION ........................................................................................ 1 3.0 TRANSIT MODES DESCRIPTION ...................................................................... 4 3.1 ENHANCED BUS SERViCES ................................................................... 4 3.2 BUS RAPID TRANSIT .............................................................................. 5 3.3 TROLLEY BUS SERVICES ...................................................................... 6 3.4 SUSPENDED/CABLEWAY TRANSIT ...................................................... 7 3.5 AUTOMATED GUIDEWAY TRANSiT ....................................................... 7 3.6 LIGHT RAIL TRANSIT .............................................................................. 8 3.7 HEAVY RAIL ............................................................................................. 8 3.8 MONORAIL -

January–June 2005 · $10.00 / Rails To

January–June 2005 · $10.00 / Rails to Rubber to Rails Again, Part 1: Alabama–Montana Headlights The Magazine of Electric Railways Published since 1939 by the Electric Railroaders’ Association, Inc. WWW.ERAUSA.ORG Staff Contents Editor and Art Director January–June 2005 Sandy Campbell Associate Editors Raymond R. Berger, Frank S. Miklos, John Pappas Contributors Edward Ridolph, Trevor Logan, Bill Volkmer, Columns Alan K. Weeks 2 News Electric Railroaders’ Compiled by Frank Miklos. International transportation reports. Association, Inc. E Two-Part Cover Story Board of Directors 2008 President 18 Rails to Rubber to Rails Again Frank S. Miklos By Edward Ridolph. An extensive 60-year summary of the street railway industry in First Vice President the U.S. and Canada, starting with its precipitous 30-year, post-World War II decline. William K. Guild It continues with the industry’s rebirth under the banner of “light rail” in the early Second Vice President & Corresponding Secretary 1980s, a renaissance which continues to this day. Raymond R. Berger Third Vice President & Recording Secretary Robert J. Newhouser Below: LAMTA P3 3156 is eastbound across the First Street bridge over the Los Treasurer Angeles River in the waning weeks of service before abandonment of Los Angeles’ Michael Glikin narrow gauge system on March 31, 1963. GERALD SQUIER PHOTO Director Jeffrey Erlitz Membership Secretary Sandy Campbell Officers 2008 Trip & Convention Chairman Jack May Librarian William K. Guild Manager of Publication Sales Raymond R. Berger Overseas Liason Officer James Mattina National Headquarters Grand Central Terminal, New York City A-Tower, Room 4A Mailing Address P.O. -

CHRISTOPHER PATTON, Plaintiff, V. SEPTA, Faye LM Moore, and Cecil

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA : CHRISTOPHER PATTON, : Plaintiff, : CIVIL ACTION : v. : NO. 06-707 : SEPTA, Faye L. M. Moore, : and Cecil W. Bond Jr., : Defendants. : Memorandum and Order YOHN, J. January ___, 2007 Plaintiff Christopher Patton brings the instant action pursuant to the Americans with Disabilities Act, 42 U.S.C. § 12101 et seq . (“ADA”); the Rehabilitation Act, 29 U.S.C. § 701 et seq.; 42 U.S.C. § 1983; the Pennsylvania Human Relations Act, 43 Pa. Cons. Stat. § 955(a) (“PHRA”); and Article I of the Pennsylvania Constitution, against defendants Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (“SEPTA”); SEPTA’s General Manager, Faye L. M. Moore; and SEPTA’s Assistant General Manager, Cecil W. Bond Jr. (collectively, “defendants”). Presently before the court is defendants’ motion to dismiss pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6) or, in the alternative, for summary judgment pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 56, as to plaintiff’s claims under the PHRA against defendants Moore and Bond (Counts VII and VIII), plaintiff’s claims for violation of the Pennsylvania Constitution (Counts XI, XII, and XIII) and plaintiff’s demand for punitive damages. For the following reasons, defendants’ motion will be granted in part and denied in part. 1 I. Factual and Procedural Background A. Plaintiff’s Factual Allegations Plaintiff was hired by SEPTA on December 8, 1997 to develop and direct its Capital and Long Range Planning Department. (Second Am. Compl. (“Compl.”) ¶ 14.) Defendant Moore, is the General Manager of SEPTA (id . at ¶¶ 6, 13); defendant Bond is the Assistant General Manager of SEPTA (id. -

Trolleys Through the Timber - Richard Thompson

Oregon Electric Railway Historical Society Volume 19 503 Issue 2 Spring 2014 Reminder to members: Please be sure your dues In this issue: are up to date. 2014 dues were due Jan 1, 2014. Trolleys Through the Timber - Richard Thompson....................1 Oregon Electric Railway Historical Society News.......................2 If it has been longer than one year since you renewed, Interpretative Center Update Greg Bonn....................................2 go to our website: oerhs.org and download an Red Trolleys in the Sun Mark Kavanagh..................................5 application by clicking: Become a Member MAX Yellow Line Lou Bowerman ..............................................6 Seattle Transit Update Roy Bonn................................................7 Tucson Sun Link Update Roy Bonn............................................9 See this issue in color on line DC Streetcar Update Roy Bonn..............................................10 at oerhs.org/transfer Pacific Northwest Transit Update Roy Bonn..............................10 Spotlight on Members: Hal Rosene ..........................................11 Trolleys Through the Timber Oregon’s Small Town Streetcar Systems By Richard Thompson The following article is excerpted from Richard's upcoming book, “Trolleys Through the Timber: Oregon's Small Town Streetcar Systems.” As the working title indicates, it will focus upon streetcars outside of Portland. This new endeavor will allow the author to further develop information about small town streetcar systems that previously appeared in his online Oregon Encyclopedia entries, and his four books for Arcadia Publishing. By the turn of the 20th century the Small town streetcar systems often relied on secondhand rolling stock. This interurban- street railway had become a vital part of like Forest Grove Transportation Company car is thought to have started life as a trailer urban transportation. -

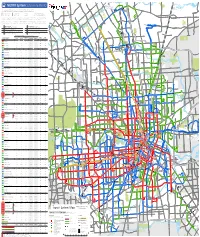

TRANSIT SYSTEM MAP Local Routes E

Non-Metro Service 99 Woodlands Express operates three Park & 99 METRO System Sistema de METRO Ride lots with service to the Texas Medical W Center, Greenway Plaza and Downtown. To Kingwood P&R: (see Park & Ride information on reverse) H 255, 259 CALI DR A To Townsen P&R: HOLLOW TREE LN R Houston D 256, 257, 259 Northwest Y (see map on reverse) 86 SPRING R E Routes are color-coded based on service frequency during the midday and weekend periods: Medical F M D 91 60 Las rutas están coloradas por la frecuencia de servicio durante el mediodía y los fines de semana. Center 86 99 P&R E I H 45 M A P §¨¦ R E R D 15 minutes or better 20 or 30 minutes 60 minutes Weekday peak periods only T IA Y C L J FM 1960 V R 15 minutes o mejor 20 o 30 minutos 60 minutos Solo horas pico de días laborales E A D S L 99 T L E E R Y B ELLA BLVD D SPUR 184 FM 1960 LV R D 1ST ST S Lone Star Routes with two colors have variations in frequency (e.g. 15 / 30 minutes) on different segments as shown on the System Map. T A U College L E D Peak service is approximately 2.5 hours in the morning and 3 hours in the afternoon. Exact times will vary by route. B I N N 249 E 86 99 D E R R K ") LOUETTA RD EY RD E RICHEY W A RICH E RI E N K W S R L U S Rutas con dos colores (e.g. -

Rider Guide / Guía De Pasajeros

Updated 02/10/2019 Rider Guide / Guía de Pasajeros Stations / Estaciones Stations / Estaciones Northline Transit Center/HCC Theater District Melbourne/North Lindale Central Station Capitol Lindale Park Central Station Rusk Cavalcade Convention District Moody Park EaDo/Stadium Fulton/North Central Coffee Plant/Second Ward Quitman/Near Northside Lockwood/Eastwood Burnett Transit Center/Casa De Amigos Altic/Howard Hughes UH Downtown Cesar Chavez/67th St Preston Magnolia Park Transit Center Central Station Main l Transfer to Green or Purple Rail Lines (see map) Destination Signs / Letreros Direccionales Westbound – Central Station Capitol Eastbound – Central Station Rusk Eastbound Theater District to Magnolia Park Hacia el este Magnolia Park Main Street Square Bell Westbound Magnolia Park to Theater District Downtown Transit Center Hacia el oeste Theater District McGowen Ensemble/HCC Wheeler Transit Center Museum District Hermann Park/Rice U Stations / Estaciones Memorial Hermann Hospital/Houston Zoo Theater District Dryden/TMC Central Station Capitol TMC Transit Center Central Station Rusk Smith Lands Convention District Stadium Park/Astrodome EaDo/Stadium Fannin South Leeland/Third Ward Elgin/Third Ward Destination Signs / Letreros Direccionales TSU/UH Athletics District Northbound Fannin South to Northline/HCC UH South/University Oaks Hacia el norte Northline/HCC MacGregor Park/Martin Luther King, Jr. Southbound Northline/HCC to Fannin South Palm Center Transit Center Hacia el sur Fannin South Destination Signs / Letreros Direccionales Eastbound Theater District to Palm Center TC Hacia el este Palm Center Transit Center Westbound Palm Center TC to Theater District Hacia el oeste Theater District The Fare/Pasaje / Local Make Your Ride on METRORail Viaje en METRORail Rápido y Fare Type Full Fare* Discounted** Transfer*** Fast and Easy Fácil Tipo de Pasaje Pasaje Completo* Descontado** Transbordo*** 1. -

The Streetcar Conspiracy

The StreetCar Conspiracy How General Motors Deliberately Destroyed Public Transit by Bradford Snell The electric streetcar, contrary to Van Wilkin's incredible naïve whitewash, did not die a natural death: General Motors killed it. GM killed it by employing a host of anti-competitive devices which, like National City Lines, debased rail transit and promoted auto sales. This is not about a "plot" hatch by wild-eyed corporate rogues, but rather about a consummate business strategy crafted by Alfred P. Sloan, Jr., the MIT-trained genius behind General Motors, to expand auto sales and maximize profits by eliminating streetcars. In 1922, according to GM's own files, Sloan established a special unit within the corporation which was charged, among other things, with the task of replacing America's electric railways with cars, trucks and buses. A year earlier, in 1921, GM lost $65 million, leading Sloan to conclude that the auto market was saturated, that those who desired cars already owned them, and that the only way to increase GM's sales and restore its profitability was by eliminating its principal rival: electric railways. At the time, 90 percent of all trips were by rail, chiefly electric rail; only one in 10 Americans owned an automobile. There were 1,200 separate electric street and interurban railways, a thriving and profitable industry with 44,000 miles of track, 300,000 employees, 15 billion annual passengers, and $1 billion in income. Virtually every city and town in America of more than 2,500 people had its own electric rail system. General Motors sought to reduce competition from electric railways through a variety of measures, including the use of freight leverage. -

Service Guidelines and Standards

Service Guidelines and Standards Revised Summer 2015 Capital Metropolitan Transportation Authority | Austin, Texas TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Purpose 3 Overview 3 Update 3 Service Types 4 SERVICE GUIDELINES Density and Service Coverage 5 Land Use 6 Destinations and Activity Centers 6 Streets and Sidewalk Characteristics 7 Demographic and Socioeconomic Characteristics 7 Route Directness 8 Route Deviation 9 Two-way Service 10 Branching and Short-Turns 10 Route Spacing 11 Route Length 11 Route Terminals 11 Service Span 12 Service Frequency 12 Bus Stop Spacing 13 Bus Stop Placement 13 Bus Stop Amenities 14 MetroRapid Stations vs. Bus Stops 15 Transit Centers and Park & Rides 15 SERVICE STANDARDS Schedule Reliability 19 Load Factors 19 Ridership Productivity and Cost-Effectiveness 20 Potential Corrective Actions 21 New and Altered Services 21 Service Change Process 22 APPENDIX A1: Map – Households without Access to an Automobile 24 A2: Map – Elderly Population Exceeding 10% of Total Population 25 A3: Map - Youth Population Exceeding 25% by Census Block 26 A4: Map – Household Income Below 50% of Regional Median 27 B1: Chart – Park & Ride Level of Service (LOS) Amenities 28 Service Guidelines and Standards INTRODUCTION Purpose The Capital Metropolitan Transportation Authority connects people, jobs and communities by providing quality transportation choices. Service guidelines and standards reflect the goals and objectives of the Authority. Capital Metro Strategic Goals: 1) Provide a Great Customer Experience 2) Improve Business Practices 3) Demonstrate the Value of Public Transportation in an Active Community 4) Be a Regional Leader Overview Service guidelines provide a framework for the provision, design, and allocation of service. Service guidelines incorporate transit service planning factors including residential and employment density, land use, activity centers, street characteristics, and demographics. -

1 | Page Date: December 7, 2017 To: Neil Mcfarlane General Manager From

Date: December 7, 2017 To: Neil McFarlane General Manager From: Erik Van Hagen Senior Deputy General Counsel Subject: Recommendations for Administrative Resolution of Fare Evasion Citations In advance of the TriMet Board of Directors December 13 briefing, this memorandum outlines recommendations for the Board as it considers upcoming changes to fare evasion penalties based on the newly enacted administrative option for citations as provided for in HB 2777. This memorandum is intended to provide both the Board of Directors and the public an opportunity to understand the rationale for the recommendations and allow the public to offer feedback to the Board in advance of the January 24, 2018, first reading of an ordinance to adopt administrative penalties for fare evasion. SUMMARY Following extensive outreach and planning, and for the reasons outlined in greater detail below, the following four recommendations are offered as administrative penalties for adult fare evasion in the forthcoming administrative process authorized by HB 2777: 1. Fines. If paid during the ninety (90)-day stay period, the presumptive fine should be reduced to the following amounts: -First offense: $75 -Second offense: $100 -Third offense: $150 -Fourth offense and beyond: $175 (no reduction) 2. Community Service. In lieu of a fine payment, the cited party should be allowed to complete community service as follows: -First offense: 4 hours -Second offense: 7 hours -Third offense: 12 hours -Fourth offense and beyond: 15 hours 1 | Page 3. Low income/Honored Citizen Option. For those customers cited for fare evasion who: (1) are eligible for (but not enrolled in) TriMet’s Low Income Fare or Honored Citizen programs; (2) successfully enroll in the Low Income Fare or Honored Citizen program during the 90-day stay period; and (3) load a minimum of $10 on their reloadable fare card during the 90-day stay period, TriMet will reduce the citation to $0 following verification of the above. -

Notice of Public Hearings Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority Docket B15-03: Proposed Metrobus Service and Tariff Changes

Notice of Public Hearings Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority Docket B15-03: Proposed Metrobus Service and Tariff Changes Purpose Notice is hereby given that a public hearing will be held by the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority on the docket mentioned above as follows: Hearing No. 606 Thursday, September 17, 2015 Metro Headquarters Building 600 5th Street, NW Washington, DC Information Session at 6 p.m. – Public Hearing at 6:30 p.m. Please note that this date is subject to the facility’s cancellation policy. The locations for all public hearings are wheelchair accessible. Any individual who requires special assistance such as a sign language interpreter or additional accommodation to participate in the public hearing, or who requires these materials in an alternate format, should contact Danise Peña at 202-962-2511 or TTY: 202-962-2033 as soon as possible in order for Metro to make necessary arrangements. For language assistance, such as an interpreter or information in another language, please call 202-962-2582 at least 48 hours prior to the public hearing date. For more information please visit www.wmata.com/hearings and www.wmata.com/betterbus. HOW TO REGISTER TO SPEAK – All organizations or individuals desiring to be heard with respect to the docket will be afforded the opportunity to present their views and make supporting statements and to offer alternative proposals. In order to establish a witness list, individuals and representatives of organizations who wish to be heard at these public hearings are requested to furnish in writing their name and organization affiliation, if any, via email to [email protected].