CHRISTOPHER PATTON, Plaintiff, V. SEPTA, Faye LM Moore, and Cecil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metrorail/Coconut Grove Connection Study Phase II Technical

METRORAILICOCONUT GROVE CONNECTION STUDY DRAFT BACKGROUND RESEARCH Technical Memorandum Number 2 & TECHNICAL DATA DEVELOPMENT Technical Memorandum Number 3 Prepared for Prepared by IIStB Reynolds, Smith and Hills, Inc. 6161 Blue Lagoon Drive, Suite 200 Miami, Florida 33126 December 2004 METRORAIUCOCONUT GROVE CONNECTION STUDY DRAFT BACKGROUND RESEARCH Technical Memorandum Number 2 Prepared for Prepared by BS'R Reynolds, Smith and Hills, Inc. 6161 Blue Lagoon Drive, Suite 200 Miami, Florida 33126 December 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 1 2.0 STUDY DESCRiPTION ........................................................................................ 1 3.0 TRANSIT MODES DESCRIPTION ...................................................................... 4 3.1 ENHANCED BUS SERViCES ................................................................... 4 3.2 BUS RAPID TRANSIT .............................................................................. 5 3.3 TROLLEY BUS SERVICES ...................................................................... 6 3.4 SUSPENDED/CABLEWAY TRANSIT ...................................................... 7 3.5 AUTOMATED GUIDEWAY TRANSiT ....................................................... 7 3.6 LIGHT RAIL TRANSIT .............................................................................. 8 3.7 HEAVY RAIL ............................................................................................. 8 3.8 MONORAIL -

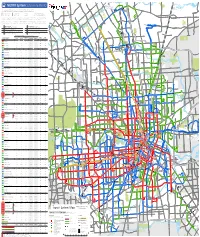

TRANSIT SYSTEM MAP Local Routes E

Non-Metro Service 99 Woodlands Express operates three Park & 99 METRO System Sistema de METRO Ride lots with service to the Texas Medical W Center, Greenway Plaza and Downtown. To Kingwood P&R: (see Park & Ride information on reverse) H 255, 259 CALI DR A To Townsen P&R: HOLLOW TREE LN R Houston D 256, 257, 259 Northwest Y (see map on reverse) 86 SPRING R E Routes are color-coded based on service frequency during the midday and weekend periods: Medical F M D 91 60 Las rutas están coloradas por la frecuencia de servicio durante el mediodía y los fines de semana. Center 86 99 P&R E I H 45 M A P §¨¦ R E R D 15 minutes or better 20 or 30 minutes 60 minutes Weekday peak periods only T IA Y C L J FM 1960 V R 15 minutes o mejor 20 o 30 minutos 60 minutos Solo horas pico de días laborales E A D S L 99 T L E E R Y B ELLA BLVD D SPUR 184 FM 1960 LV R D 1ST ST S Lone Star Routes with two colors have variations in frequency (e.g. 15 / 30 minutes) on different segments as shown on the System Map. T A U College L E D Peak service is approximately 2.5 hours in the morning and 3 hours in the afternoon. Exact times will vary by route. B I N N 249 E 86 99 D E R R K ") LOUETTA RD EY RD E RICHEY W A RICH E RI E N K W S R L U S Rutas con dos colores (e.g. -

Rider Guide / Guía De Pasajeros

Updated 02/10/2019 Rider Guide / Guía de Pasajeros Stations / Estaciones Stations / Estaciones Northline Transit Center/HCC Theater District Melbourne/North Lindale Central Station Capitol Lindale Park Central Station Rusk Cavalcade Convention District Moody Park EaDo/Stadium Fulton/North Central Coffee Plant/Second Ward Quitman/Near Northside Lockwood/Eastwood Burnett Transit Center/Casa De Amigos Altic/Howard Hughes UH Downtown Cesar Chavez/67th St Preston Magnolia Park Transit Center Central Station Main l Transfer to Green or Purple Rail Lines (see map) Destination Signs / Letreros Direccionales Westbound – Central Station Capitol Eastbound – Central Station Rusk Eastbound Theater District to Magnolia Park Hacia el este Magnolia Park Main Street Square Bell Westbound Magnolia Park to Theater District Downtown Transit Center Hacia el oeste Theater District McGowen Ensemble/HCC Wheeler Transit Center Museum District Hermann Park/Rice U Stations / Estaciones Memorial Hermann Hospital/Houston Zoo Theater District Dryden/TMC Central Station Capitol TMC Transit Center Central Station Rusk Smith Lands Convention District Stadium Park/Astrodome EaDo/Stadium Fannin South Leeland/Third Ward Elgin/Third Ward Destination Signs / Letreros Direccionales TSU/UH Athletics District Northbound Fannin South to Northline/HCC UH South/University Oaks Hacia el norte Northline/HCC MacGregor Park/Martin Luther King, Jr. Southbound Northline/HCC to Fannin South Palm Center Transit Center Hacia el sur Fannin South Destination Signs / Letreros Direccionales Eastbound Theater District to Palm Center TC Hacia el este Palm Center Transit Center Westbound Palm Center TC to Theater District Hacia el oeste Theater District The Fare/Pasaje / Local Make Your Ride on METRORail Viaje en METRORail Rápido y Fare Type Full Fare* Discounted** Transfer*** Fast and Easy Fácil Tipo de Pasaje Pasaje Completo* Descontado** Transbordo*** 1. -

Service Guidelines and Standards

Service Guidelines and Standards Revised Summer 2015 Capital Metropolitan Transportation Authority | Austin, Texas TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Purpose 3 Overview 3 Update 3 Service Types 4 SERVICE GUIDELINES Density and Service Coverage 5 Land Use 6 Destinations and Activity Centers 6 Streets and Sidewalk Characteristics 7 Demographic and Socioeconomic Characteristics 7 Route Directness 8 Route Deviation 9 Two-way Service 10 Branching and Short-Turns 10 Route Spacing 11 Route Length 11 Route Terminals 11 Service Span 12 Service Frequency 12 Bus Stop Spacing 13 Bus Stop Placement 13 Bus Stop Amenities 14 MetroRapid Stations vs. Bus Stops 15 Transit Centers and Park & Rides 15 SERVICE STANDARDS Schedule Reliability 19 Load Factors 19 Ridership Productivity and Cost-Effectiveness 20 Potential Corrective Actions 21 New and Altered Services 21 Service Change Process 22 APPENDIX A1: Map – Households without Access to an Automobile 24 A2: Map – Elderly Population Exceeding 10% of Total Population 25 A3: Map - Youth Population Exceeding 25% by Census Block 26 A4: Map – Household Income Below 50% of Regional Median 27 B1: Chart – Park & Ride Level of Service (LOS) Amenities 28 Service Guidelines and Standards INTRODUCTION Purpose The Capital Metropolitan Transportation Authority connects people, jobs and communities by providing quality transportation choices. Service guidelines and standards reflect the goals and objectives of the Authority. Capital Metro Strategic Goals: 1) Provide a Great Customer Experience 2) Improve Business Practices 3) Demonstrate the Value of Public Transportation in an Active Community 4) Be a Regional Leader Overview Service guidelines provide a framework for the provision, design, and allocation of service. Service guidelines incorporate transit service planning factors including residential and employment density, land use, activity centers, street characteristics, and demographics. -

1 | Page Date: December 7, 2017 To: Neil Mcfarlane General Manager From

Date: December 7, 2017 To: Neil McFarlane General Manager From: Erik Van Hagen Senior Deputy General Counsel Subject: Recommendations for Administrative Resolution of Fare Evasion Citations In advance of the TriMet Board of Directors December 13 briefing, this memorandum outlines recommendations for the Board as it considers upcoming changes to fare evasion penalties based on the newly enacted administrative option for citations as provided for in HB 2777. This memorandum is intended to provide both the Board of Directors and the public an opportunity to understand the rationale for the recommendations and allow the public to offer feedback to the Board in advance of the January 24, 2018, first reading of an ordinance to adopt administrative penalties for fare evasion. SUMMARY Following extensive outreach and planning, and for the reasons outlined in greater detail below, the following four recommendations are offered as administrative penalties for adult fare evasion in the forthcoming administrative process authorized by HB 2777: 1. Fines. If paid during the ninety (90)-day stay period, the presumptive fine should be reduced to the following amounts: -First offense: $75 -Second offense: $100 -Third offense: $150 -Fourth offense and beyond: $175 (no reduction) 2. Community Service. In lieu of a fine payment, the cited party should be allowed to complete community service as follows: -First offense: 4 hours -Second offense: 7 hours -Third offense: 12 hours -Fourth offense and beyond: 15 hours 1 | Page 3. Low income/Honored Citizen Option. For those customers cited for fare evasion who: (1) are eligible for (but not enrolled in) TriMet’s Low Income Fare or Honored Citizen programs; (2) successfully enroll in the Low Income Fare or Honored Citizen program during the 90-day stay period; and (3) load a minimum of $10 on their reloadable fare card during the 90-day stay period, TriMet will reduce the citation to $0 following verification of the above. -

Notice of Public Hearings Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority Docket B15-03: Proposed Metrobus Service and Tariff Changes

Notice of Public Hearings Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority Docket B15-03: Proposed Metrobus Service and Tariff Changes Purpose Notice is hereby given that a public hearing will be held by the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority on the docket mentioned above as follows: Hearing No. 606 Thursday, September 17, 2015 Metro Headquarters Building 600 5th Street, NW Washington, DC Information Session at 6 p.m. – Public Hearing at 6:30 p.m. Please note that this date is subject to the facility’s cancellation policy. The locations for all public hearings are wheelchair accessible. Any individual who requires special assistance such as a sign language interpreter or additional accommodation to participate in the public hearing, or who requires these materials in an alternate format, should contact Danise Peña at 202-962-2511 or TTY: 202-962-2033 as soon as possible in order for Metro to make necessary arrangements. For language assistance, such as an interpreter or information in another language, please call 202-962-2582 at least 48 hours prior to the public hearing date. For more information please visit www.wmata.com/hearings and www.wmata.com/betterbus. HOW TO REGISTER TO SPEAK – All organizations or individuals desiring to be heard with respect to the docket will be afforded the opportunity to present their views and make supporting statements and to offer alternative proposals. In order to establish a witness list, individuals and representatives of organizations who wish to be heard at these public hearings are requested to furnish in writing their name and organization affiliation, if any, via email to [email protected]. -

Equity in Transit: 2020

Equity in Transit: 2020 a LINK HOUSTON Hugo Guerrero LINK Houston is a 501(c) (3) nonprofit organization that advocates for a robust and equitable transporta- Sixth Ward Resident tion network so that all people can reach opportunity. We envision a world in which all people in Houston can easily access not only jobs but also educational experiences, medical appointments, grocery stores, greenspace, and other important destinations, regard- less of their mode of transportation. To make that vision a reality, we support transformative and inclu- sive policies, systems, initiatives, and infrastructure development that connect people to opportunity by transit, walking, rolling, and biking. We move ideas into action through community engagement, research, and shaping public policy. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Richard Petty (Chair) Co-Director, Independent Living Research Utilization, TIRR Memorial Hermann Elizabeth Love Senior Program Officer, Houston Endowment Bill Fulton Director, Kinder Institute for Urban Research, Rice University Dr. Denae King Associate Director, Texas Southern University Michael Skelly Senior Advisor, Lazard “I live in the historic Sixth Ward. My Janis Scott Houston’s “Bus Lady” primary method of getting around is Adrienne Mangual Executive Director of public transportation. I can catch the bus Strategy and Planning, one block from the house, and it takes Prime Communications me to the office in Downtown, my kids’ Amanda Timm Principal Owner, daycare in Midtown, doctor’s or dentist’s Amanda Timm Consulting appointments in Downtown, or any James Llamas Principal, sporting event. On the weekends, the kids Traffic Engineers, Inc. and I ride our bikes to the METRO Rail to get to the Museum District and/or the zoo. -

City of Mesa Business Assistance

CITY OF MESA BUSINESS ASSISTANCE BUSINESS ADVOCACY PARTNERS Shea Joachim | 480.644.3562 | mesaaz.gov/economic Downtown Mesa Association (DMA) PROJECT WEBSITE David Short | 480.890.2613 | downtownmesa.com The city of Mesa has developed a website with Central Mesa extension project information and various business assistance programs available to business owners affected by construction. The Downtown Mesa Association is a Special Improvement District dedicated to economic growth Visit mesaaz.gov/lightrail for project information. and business development in the square mile of downtown Mesa. DMA offers assistance for these area businesses, including maintenance, marketing and promotion, special event advertising and general business support. WAYFINDING AND SIGNAGE The city of Mesa has installed new signs in order to promote accessible parking and business Friends of access points for downtown. This includes color-coded parking lot designations so business owners TRANSIT and staff can better direct their customers to the parking areas that are most convenient. A map SERVING THE GREATER PHOENIX REGION showing the free parking areas for downtown Mesa can be viewed at mesaaz.gov/lightrail/images/ Friends of Transit WhereToPark.pdf. David Schwartz | 602.277.0911 | friendsoftransit.org Friends of Transit is a grassroots organization that serves as a resource to the Greater Phoenix BUSINESS OMBUDSMAN community on the benefits and importance of a well-designed and accessible mass transit system. The city of Mesa has dedicated an economic development staff member to provide business During light rail construction of the Central Mesa extension, Friends of Transit has supported local businesses by sponsoring an event series known as Mesa Mixers. -

History of MDOT MTA and the Lots System

History of Transit Organization in the Baltimore Region Transit Agencies and Service Development in the Baltimore Region OVERVIEW The Baltimore Regional Transit Governance and Funding Study will develop alternatives for how the region could structure, organize, and fund regional transit services. The approach to developing these alternatives includes working with the Baltimore Regional Transit Board (BRTB) through an iterative process of research, analysis, and stakeholder input to ensure that the alternatives are grounded in experience, respectful of history and constraints, but creative enough to recognize opportunities. This technical memo, the first in the series, focuses on the history and development of transit services in the Baltimore Region. The first step involves focusing on the history and development of transit Image from Creative Commons: ETLamborghini services in the Baltimore region to understand how the existing service network came to be and provides the context for why some regional services are operated by the Maryland Transit Administration (MTA) and others by Locally Operated Transit Systems (LOTS). Our goal is that by understanding the historical perspective, we will understand the transit network, its origins and evolution and its current form. The overview and historical perspective include the development and evolution of: • State leadership for local transit services in the City of Baltimore. • State leadership for regional transit services, including the MARC commuter rail system and the Commuter Bus program. Nelson\Nygaard Consulting Associates Inc. | KFH Group | KPMG | Tamar Henkin 1 History of Transit Organization in the Baltimore Region • County leadership for local services in the counties surrounding Baltimore through the Locally Operated Transit System (LOTS) program. -

(CITT) Metrorail Maintenance Assessment Final Report Prepared By

Citizens’ Independent Transportation Trust (CITT) Metrorail Maintenance Assessment Final Report prepared by June 19th, 2019 CITT Metrorail Maintenance Assessment June 19, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 1 2 METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................................ 4 2.1 Scope of Work ............................................................................................... 4 2.2 Data gathering methods ................................................................................. 6 3 CURRENT FLEET AVAILABILITY AND RELIABILITY ................................................................ 8 3.1 Service Availability ......................................................................................... 8 3.2 Vehicle Availability ....................................................................................... 11 4 FLEET MAINTENANCE ............................................................................................... 14 4.1 Adherence to manuals and preventive maintenance schedule .......................... 14 4.2 Vehicle mid-life overhaul .............................................................................. 17 4.3 Manuals for new fleet ................................................................................... 17 4.4 Asset management practices ........................................................................ 18 4.5 Availability -

Maryland Rail Time-Of-Day Direct Ridership Model Final Report

The National Center for Smart Growth Research and Education University of Maryland, College Park in partnership with The Maryland Department of Transportation Time-of-Day Direct Ridership Model for Maryland Rail Transit Final Report July 21st, 2017 Prepared by: Chao Liu, Ph.D., Faculty Research Associate Hiroyuki Iseki, Ph.D., Research Faculty, Assistant Professor Sicheng Wang, Research Assistant The views expressed in this report are those of The National Center for Smart Growth Research and Education, and do not necessarily represent those of the University of Maryland or the Maryland Department of Transportation, or the State of Maryland Table of Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction – Study Objective ........................................................................................... 1 2. Study Area, Data, and Data Sources ................................................................................... 2 2.1. Rail Stations in the Model Development ......................................................................................... 2 2.2. Data and Primary Data Sources ......................................................................................................... 4 Definition of Station Area .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Rail Ridership by Station by Time of Day -

A Philadelphia Youth Rider Agenda

A Philadelphia Youth Rider Agenda A report by the SEPTA Youth Advisory Council “Getting Youth on Board with SEPTA” Table of Contents • Letter from the Chair 3 • Authorship 4 • Acknowledgements 5 • Introduction 7 o About the YAC 7 o Service Evaluation 7 o Purpose of this report 8 • Survey Process and Methodology 8 o Philadelphia Youth Rider Survey 8 • College Students 8 • High School Students 9 o Youth Rider Forum 9 o Data Analysis 10 • Results: Understanding Youth Rider Needs 11 • Recommendations 16 o Core Recommendations 17 o Other Recommendations 28 • Recommendations for Further Study 30 2 Letter from the Chair Dear SEPTA rider, It is my pleasure to present you with an extraordinary achievement from the youth of the Philadelphia region. In a recent interview about the SEPTA Youth Advisory Council (YAC), I was asked if I thought that our generation was starting to favor public transit over private automobiles. While it may still be premature to speculate about how today’s youth will compare to their predecessors, it’s not too early to recognize that public transit will be an ever-more vital resource to young people in years to come. As world population increases and becomes more urban, providing for sustainable and accessible cities and regions will require greater reliance on viable public transportation networks— and the rise of a generation that is comfortable with using them. Creating a culture of transit ridership is no easy task, but if Philadelphia is serious about becoming “the greenest city in America,” it’s a good place to start. In the broadest sense, this report is the SEPTA Youth Advisory Council’s first answer to how we can approach that challenge.