International Review of the Red Cross, January-February 1994

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One Hundred Years of Thomism Aeterni Patris and Afterwards a Symposium

One Hundred Years of Thomism Aeterni Patris and Afterwards A Symposium Edited By Victor B. Brezik, C.S.B, CENTER FOR THOMISTIC STUDIES University of St. Thomas Houston, Texas 77006 ~ NIHIL OBSTAT: ReverendJamesK. Contents Farge, C.S.B. Censor Deputatus INTRODUCTION . 1 IMPRIMATUR: LOOKING AT THE PAST . 5 Most Reverend John L. Morkovsky, S.T.D. A Remembrance Of Pope Leo XIII: The Encyclical Aeterni Patris, Leonard E. Boyle,O.P. 7 Bishop of Galveston-Houston Commentary, James A. Weisheipl, O.P. ..23 January 6, 1981 The Legacy Of Etienne Gilson, Armand A. Maurer,C.S.B . .28 The Legacy Of Jacques Maritain, Christian Philosopher, First Printing: April 1981 Donald A. Gallagher. .45 LOOKING AT THE PRESENT. .61 Copyright©1981 by The Center For Thomistic Studies Reflections On Christian Philosophy, All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or Ralph McInerny . .63 reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written Thomism And Today's Crisis In Moral Values, Michael permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in Bertram Crowe . .74 critical articles and reviews. For information, write to The Transcendental Thomism, A Critical Assessment, Center For Thomistic Studies, 3812 Montrose Boulevard, Robert J. Henle, S.J. 90 Houston, Texas 77006. LOOKING AT THE FUTURE. .117 Library of Congress catalog card number: 80-70377 Can St. Thomas Speak To The Modem World?, Leo Sweeney, S.J. .119 The Future Of Thomistic Metaphysics, ISBN 0-9605456-0-3 Joseph Owens, C.Ss.R. .142 EPILOGUE. .163 The New Center And The Intellectualism Of St. Thomas, Printed in the United States of America Vernon J. -

New Books for December 2019 Grace, Predestination, and the Permission of Sin: a Thomistic Analysis by O'neill, Taylor Patrick, A

New Books for December 2019 Grace, predestination, and the permission of sin: a Thomistic analysis by O'Neill, Taylor Patrick, author. Book B765.T54 O56 2019 Faith and the founders of the American republic Book BL2525 .F325 2014 Moral combat: how sex divided American Christians and fractured American politics by Griffith, R. Marie 1967- author. (Ruth Marie), Book BR516 .G75 2017 Southern religion and Christian diversity in the twentieth century by Flynt, Wayne, 1940- author. Book BR535 .F59 2016 The story of Latino Protestants in the United States by Martínez, Juan Francisco, 1957- author. Book BR563.H57 M362 2018 The land of Israel in the Book of Ezekiel by Pikor, Wojciech, Book BS1199.L28 P55 2018 2 Kings by Park, Song-Mi Suzie, author. Book BS1335.53 .P37 2019 The Parables in Q by Roth, Dieter T., author. Book BS2555.52 .R68 2018 Hearing Revelation 1-3: listening with Greek rhetoric and culture by Neyrey, Jerome H., 1940- author. Book BS2825.52 .N495 2019 "Your God is a devouring fire": fire as a motif of divine presence and agency in the Hebrew Bible by Simone, Michael R., 1972- author. Book BS680.F53 S56 2019 Trinitarian and cosmotheandric vision by Panikkar, Raimon, Book BT111.3 .P36 2019 The life of Jesus: a graphic novel by Alex, Ben, author. Book BT302 .M66 2017 Our Lady of Guadalupe: the graphic novel by Muglia, Natalie, Book BT660.G8 M84 2018 An ecological theology of liberation: salvation and political ecology by Castillo, Daniel Patrick, author. Book BT83.57 .C365 2019 The Satan: how God's executioner became the enemy by Stokes, Ryan E., Book BT982 .S76 2019 Lectio Divina of the Gospels: for the liturgical year 2019-2020. -

Cod Report Template

EN CD/17/19 Original: English For information COUNCIL OF DELEGATES OF THE INTERNATIONAL RED CROSS AND RED CRESCENT MOVEMENT Antalya, Turkey 10–11 November 2017 Strengthening the Statutory and Legal Base Instruments of National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies and National Society Legal and Statutory Base Guidance and Process Review PROGRESS REPORT Document prepared by the Joint ICRC/International Federation Commission for National Society Statutes in consultation with the National Societies and the Core Group established for the National Society Legal and Statutory Base Guidance and Process Review Geneva, September 2017 1 CD/17/19 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Strong National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies are key actors and contributors to strengthened local humanitarian action and can therefore be considered crucial elements in meeting the localization agenda, which forms an important part of the outcome of the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit: the Grand Bargain. Having sound legal (recognition acts) and statutory (constitutions or statutes) base texts is a precondition for a strong National Society. They describe the identity of the National Society and explain its leadership model. They are key in safeguarding the integrity of the National Society and provide the foundation to ensure transparency and compliance, which are crucial elements in preventing fraud, corruption and nepotism. Promoting a strong National Society statutory and legal base remains a priority for National Societies and for the Movement as a whole, as it serves to ensure the efficiency of the National Society in the realization of its humanitarian mandates and roles, provides an element of stability and contributes to the protection of the National Society’s integrity and ability to abide by the Fundamental Principles at all times. -

The Pre-History of Subsidiarity in Leo XIII

Journal of Catholic Legal Studies Volume 56 Number 1 Article 5 The Pre-History of Subsidiarity in Leo XIII Michael P. Moreland Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcls This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Catholic Legal Studies by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FINAL_MORELAND 8/14/2018 9:10 PM THE PRE-HISTORY OF SUBSIDIARITY IN LEO XIII MICHAEL P. MORELAND† Christian Legal Thought is a much-anticipated contribution from Patrick Brennan and William Brewbaker that brings the resources of the Christian intellectual tradition to bear on law and legal education. Among its many strengths, the book deftly combines Catholic and Protestant contributions and scholarly material with more widely accessible sources such as sermons and newspaper columns. But no project aiming at a crisp and manageably-sized presentation of Christianity’s contribution to law could hope to offer a comprehensive treatment of particular themes. And so, in this brief essay, I seek to elaborate upon the treatment of the principle of subsidiarity in Catholic social thought. Subsidiarity is mentioned a handful of times in Christian Legal Thought, most squarely with a lengthy quotation from Pius XI’s articulation of the principle in Quadragesimo Anno.1 In this proposed elaboration of subsidiarity, I wish to broaden the discussion of subsidiarity historically (back a few decades from Quadragesimo Anno to the pontificate of Leo XIII) and philosophically (most especially its relation to Leo XIII’s revival of Thomism).2 Statements of the principle have historically been terse and straightforward even if the application of subsidiarity to particular legal questions has not. -

Download PDF Of

ADDRESSES OF NATIONAL RED CROSS AND RED CRESCENT SOCIETIES AFGHANISTAN — Afghan Red Crescent Society, Puli CHINA — Red Cross Society of China, 53, Ganmian Hartan, Kabul. Hutong, 100 010 Beijing. ALBANIA — Albanian Red Cross, Rue Qamil COLOMBIA — Colombian Red Cross Society, Guranjaku No. 2, Tirana. Avenida 68, No. 66-31, Apartado Aereo 11-10, ALGERIA (People's Democratic Republic of) — Bogota DE. Algerian Red Crescent, 15 bis, boulevard CONGO — Congolese Red Cross, place de la Paix, Mohamed V, Algiers. B.P. 4145, Brazzaville. COSTA RICA — Costa Rica Red Cross, Calle 14, ANDORRA — Andorra Red Cross, Prat de la Creu 22, Avenida 8, Apartado 1025, San Jose. Andorra la Vella. C6TE D'lVOIRE — Red Cross Society of Cote ANGOLA — Angola Red Cross, Av. Hoji Ya d'lvoire, B.P. 1244, Abidjan. Henda 107, 2. andar, Luanda. CROATIA — Croatian Red Cross, Ulica Crvenog kriza ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA — The Antigua and 14, 41000 Zagreb. Barbuda Red Cross Society, P.O. Box 727, St. Johns. CUBA — Cuban Red Cross, Calle Prado 206, Colon y ARGENTINA — The Argentine Red Cross, H. Trocadero, Habana 1. Yrigoyen 2068, 1089 Buenos Aires. CZECH REPUBLIC — Czech Red Cross, Thunovska AUSTRALIA — Australian Red Cross Society, 206, 18, 118 04 Prahal. Clarendon Street, East Melbourne 3002. DENMARK — Danish Red Cross, 27 Blegdamsvej, AUSTRIA — Austrian Red Cross, Wiedner Postboks 2600, 2100 K0benhavn 0. Hauptstrasse 32, Postfach 39, 1041, Vienna 4. DJIBOUTI — Red Crescent Society of Djibouti, BAHAMAS — The Bahamas Red Cross Society, P.O. B.P. 8, Djibouti. Box N-8331, Nassau. DOMINICA — Dominica Red Cross Society, P.O. Box BAHRAIN — Bahrain Red Crescent Society, P.O. -

Gen Assembly Report Extended V1

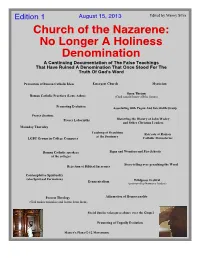

Edition 1 August 15, 2013 Edited by Manny Silva Church of the Nazarene: No Longer A Holiness Denomination A Continuing Documentation of The False Teachings That Have Ruined A Denomination That Once Stood For The Truth Of God's Word Promotion of Roman Catholic Ideas Emergent Church Mysticism Open Theism Roman Catholic Practices (Lent, Ashes) (God cannot know all the future) Promoting Evolution Associating with Pagan And Interfaith Group Prayer Stations Prayer Labyrinths Distorting the History of John Wesley and Other Christian Leaders Maunday Thursday Teaching of Occultism Retreats at Roman at the Seminary LGBT Groups in College Campuses Catholic Monasteries Roman Catholic speakers Signs and Wonders and Fire Schools at the colleges Story-telling over preaching the Word Rejection of Biblical Inerrancy Contemplative Spirituality (aka Spiritual Formation) Ecumenicalism Wildgoose Festival (promoted by Nazarene leaders) Process Theology Affirmation of Homosexuality (God makes mistakes and learns from them) Social Justice takes precedence over the Gospel Promoting of Ungodly Evolution Master's Plan (G-12 Movement) The Church of the Nazarene: General Assembly 2013 Report, And Various Papers Documenting The Heresies In The Church [This document can be copied and distributed to others to alert them to the state of the Church of the Nazarene and its universities and colleges. This document has been compiled for the sake of the brothers and sisters in Christ in the Church of the Nazarene. It is solely driven by love for those who may be, or have been, deceived by the many false teachings and teachers that have invaded the church. I cannot explain exactly why such blatantly unbiblical and satanic teachings have fooled so many. -

MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES to MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to the College of Arts and Sciences Of

MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES TO MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Matthew Glen Minix UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio December 2016 MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES TO MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Name: Minix, Matthew G. APPROVED BY: _____________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Dissertation Director _____________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Dissertation Reader. _____________________________________ Anthony Burke Smith, Ph.D. Dissertation Reader _____________________________________ John A. Inglis, Ph.D. Dissertation Reader _____________________________________ Jack J. Bauer, Ph.D. _____________________________________ Daniel Speed Thompson, Ph.D. Chair, Department of Religious Studies ii © Copyright by Matthew Glen Minix All rights reserved 2016 iii ABSTRACT MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES TO MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Name: Minix, Matthew Glen University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. Sandra A. Yocum This dissertation considers a spectrum of five distinct approaches that mid-twentieth century neo-Thomist Catholic thinkers utilized when engaging with the tradition of modern scientific psychology: a critical approach, a reformulation approach, a synthetic approach, a particular [Jungian] approach, and a personalist approach. This work argues that mid-twentieth century neo-Thomists were essentially united in their concerns about the metaphysical principles of many modern psychologists as well as in their worries that these same modern psychologists had a tendency to overlook the transcendent dimension of human existence. This work shows that the first four neo-Thomist thinkers failed to bring the traditions of neo-Thomism and modern psychology together to the extent that they suggested purely theoretical ways of reconciling them. -

Geneva 1999 Twenty-Seventh International Conference

GENEVA 1999 TWENTY-SEVENTH INTERNATIONAL +CRED CROSS RED CRESCENT CONFERENCE the power of humanity OF THE RED CROSS AND RED CRESCENT 5^/v/-mç- CO REPORT OF THE 27th INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE OF THE RED CROSS AND RED CRESCENT INCLUDING THE SUMMARY REPORT OF THE 1999 COUNCIL OF DELEGATES AND OF THE CONSTITUTIVE MEETING OF THE 13th SESSION OF THE STANDING COMMISSION Prepared by the International Committee of the Red Cross and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies GENEVA, 31 OCTOBER TO 6 NOVEMBER 1999 INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE CENTRE BIBLIOTHEQUE • OCR 19, AV. DE LA PAIX 1202 GENÈVE The 27th International Conference of the Red Cross and Red Crescent and the 1999 Council of Delegates were hosted by the International Committee of the Red Cross and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. The Standing Commission was composed of: Chairman H.R.H. Princess Margriet of the Netherlands (Netherlands Red Cross) Vice-Chairman Mr Tadateru Konoe (Japanese Red Cross Society) Members Professor Mamoun Yousif Hamid (Sudanese Red Crescent), nominated to fill the vacancy left by Dr B.R.M. Hove (Zimbabwe Red Cross Society) General Georges Harrouk (Lebanese Red Cross Society), nominated to fill the vacancy left by Dr Guillermo Rueda Montaña (Colombian Red Cross) Ms Christina Magnuson (Swedish Red Cross) Representatives of the ICRC Mr Cornelio Sommaruga, President Mr Yves Sandoz, Director Representatives of the International Federation Dr Astrid N. Heiberg, President Mr Georges Weber, Secretary General TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTORY INFORMATION................. 5 4. Officers of the 27th International 1.1 CONVOCATION....................................................... 5 Conference of the Red Cross and Red Crescent ....................................................... -

Download Article PDF , Format and Size of the File

History of humanitarian ideas The historical foundations of humanitarian action by Dr. Jean Guillermand After nearly 130 years of existence, the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement continues to play a unique and important role in the field of human relations. Its origin may be traced to the impression made on Henry Dunant, a chance witness at the scene, by the disastrous lack of medical care at the battle of Solferino in 1859 and the compassionate response aroused in the people of Lombardy by the plight of the wounded. The Movement has since gained importance and expanded to such a degree that it is now an irreplaceable institution made up of dedicated people all over the world. The Movement's success can clearly be attributed in great part to the commitment of those who carried on the pioneering work of its founders. But it is also the result of a constantly growing awareness of the conditions needed for such work to be accomplished. The initial text of the 1864 Convention was already quite explicit about its application in situations of armed conflict. Jean Pictet's analysis in 19S5 and the adoption by the Vienna Conference of the seven Fundamental Principles in 1965 have since codified in international law what was originally a generous and spontaneous impulse. In a world where the weight of hard-hitting arguments and the impact of the media play a key role in shaping public opinion, the fact that the Movement's initial spirit has survived intact and strong without having recourse to aggressive publicity campaigns or losing its independence to the political ideologies that divide the globe may well surprise an impartial observer of society today. -

The Holy See, Social Justice, and International Trade Law: Assessing the Social Mission of the Catholic Church in the Gatt-Wto System

THE HOLY SEE, SOCIAL JUSTICE, AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE LAW: ASSESSING THE SOCIAL MISSION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE GATT-WTO SYSTEM By Copyright 2014 Fr. Alphonsus Ihuoma Submitted to the graduate degree program in Law and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Juridical Science (S.J.D) ________________________________ Professor Raj Bhala (Chairperson) _______________________________ Professor Virginia Harper Ho (Member) ________________________________ Professor Uma Outka (Member) ________________________________ Richard Coll (Member) Date Defended: May 15, 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Fr. Alphonsus Ihuoma certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE HOLY SEE, SOCIAL JUSTICE, AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE LAW: ASSESSING THE SOCIAL MISSION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE GATT- WTO SYSTEM by Fr. Alphonsus Ihuoma ________________________________ Professor Raj Bhala (Chairperson) Date approved: May 15, 2014 ii ABSTRACT Man, as a person, is superior to the state, and consequently the good of the person transcends the good of the state. The philosopher Jacques Maritain developed his political philosophy thoroughly informed by his deep Catholic faith. His philosophy places the human person at the center of every action. In developing his political thought, he enumerates two principal tasks of the state as (1) to establish and preserve order, and as such, guarantee justice, and (2) to promote the common good. The state has such duties to the people because it receives its authority from the people. The people possess natural, God-given right of self-government, the exercise of which they voluntarily invest in the state. -

Addresses of National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies

ADDRESSES OF NATIONAL RED CROSS AND RED CRESCENT SOCIETIES AFGHANISTAN — Afghan Red Crescent Society, Puli COLOMBIA — Colombian Red Cross Society, Hartan, Kabul. Avenida 68, No. 66-31, Apartado Aereo 11-10, ALBANIA — Albanian Red Cross, Rue Qamil Bogotd D.E. Guranjaku No. 2, Tirana. CONGO — Congolese Red Cross, place de la Paix, ALGERIA (People's Democratic Republic of) — B.P. 4145, Brazzaville. Algerian Red Crescent, 15 bis, boulevard COSTA RICA — Costa Rica Red Cross, Calle 14, Mohamed W.Algiers. Avenida 8, Apartado 1025, San Jost. ANGOLA — Angola Red Cross, Av. Hoji Ya COTE D'lVOKE — Red Cross Society of Cote Henda 107,2. andar, Luanda. dlvoire, B.P. 1244, Abidjan. ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA — The Antigua and CUBA — Cuban Red Cross, Calle Prado 206, Coldn y Barbuda Red Cross Society, P.O. Box 727, St. Johns. Trocadero, Habana 1. ARGENTINA — The Argentine Red Cross, H. DENMARK — Danish Red Cross, 27 Blegdamsvej, Yrigoyen 2068, 7089 Buenos Aires. Postboks 2600,2100 Ktbenhavn 0. AUSTRALIA — Australian Red Cross Society, 206, DJIBOUTI — Red Crescent Society of Djibouti, Clarendon Street, East Melbourne 3002. B.P. 8, Djibouti. AUSTRIA — Austrian Red Cross, Wiedner Hauptstrasse 32, Postfach 39,1041, Vienna 4. DOMINICA — Dominica Red Cross Society, P.O. Box 59, Roseau. BAHAMAS — The Bahamas Red Cross Society, P.O. BoxN-8331,/Vajjau. DOMINICAN REPUBLIC — Dominican Red Cross, Apartado postal 1293, Santo Domingo. BAHRAIN — Bahrain Red Crescent Society, P.O. Box 882, Manama. ECUADOR — Ecuadorean Red Cross, Av. Colombia y Elizalde Esq., Quito. BANGLADESH — Bangladesh Red Crescent Society, 684-686, Bara Magh Bazar, G.P.O. Box No. 579, EGYPT — Egyptian Red Crescent Society, 29, El Galaa Dhaka. -

ABSTRACT Is “Social Justice” Justice? a Thomistic Argument For

ABSTRACT Is “Social Justice” Justice? A Thomistic Argument for “Social Persons” as the Proper Subjects of the Virtue of Social Justice John R. Lee, Ph.D. Mentor: Francis J. Beckwith, Ph.D. The term “social justice,” as it occurs in the Catholic social encyclical tradition, presents a core, definitional problem. According to Catholic social thought, social justice has social institutions as its subjects. However, in the Thomistic tradition, justice is understood to be a virtue, i.e., a human habit with human persons as subjects. Thus, with its non-personal subjects, social justice would seem not to be a virtue, and thus not to be a true form of justice. We offer a solution to this problem, based on the idea of social personhood. Drawing from the Thomistic understanding of “person” as a being “distinct in a rational nature”, it is argued that certain social institutions—those with a unity of order—are capable of meeting Aquinas’ analogical definition of personhood. Thus, social institutions with a unity of order—i.e., societies —are understood to be “social persons” and thus the proper subjects of virtue, including the virtue of justice. After a review of alternative conceptions, it is argued that “social justice” in the Catholic social encyclical tradition is best understood as general justice (justice directed toward the common good) extended to include not only human persons, but social persons as well. Advantages of this conception are highlighted. Metaphysically, an understanding of social justice as exercised by social persons fits nicely with an understanding of society as non-substantial, but subsistent being.