Luigi Taparelli and a Catholic Economics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One Hundred Years of Thomism Aeterni Patris and Afterwards a Symposium

One Hundred Years of Thomism Aeterni Patris and Afterwards A Symposium Edited By Victor B. Brezik, C.S.B, CENTER FOR THOMISTIC STUDIES University of St. Thomas Houston, Texas 77006 ~ NIHIL OBSTAT: ReverendJamesK. Contents Farge, C.S.B. Censor Deputatus INTRODUCTION . 1 IMPRIMATUR: LOOKING AT THE PAST . 5 Most Reverend John L. Morkovsky, S.T.D. A Remembrance Of Pope Leo XIII: The Encyclical Aeterni Patris, Leonard E. Boyle,O.P. 7 Bishop of Galveston-Houston Commentary, James A. Weisheipl, O.P. ..23 January 6, 1981 The Legacy Of Etienne Gilson, Armand A. Maurer,C.S.B . .28 The Legacy Of Jacques Maritain, Christian Philosopher, First Printing: April 1981 Donald A. Gallagher. .45 LOOKING AT THE PRESENT. .61 Copyright©1981 by The Center For Thomistic Studies Reflections On Christian Philosophy, All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or Ralph McInerny . .63 reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written Thomism And Today's Crisis In Moral Values, Michael permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in Bertram Crowe . .74 critical articles and reviews. For information, write to The Transcendental Thomism, A Critical Assessment, Center For Thomistic Studies, 3812 Montrose Boulevard, Robert J. Henle, S.J. 90 Houston, Texas 77006. LOOKING AT THE FUTURE. .117 Library of Congress catalog card number: 80-70377 Can St. Thomas Speak To The Modem World?, Leo Sweeney, S.J. .119 The Future Of Thomistic Metaphysics, ISBN 0-9605456-0-3 Joseph Owens, C.Ss.R. .142 EPILOGUE. .163 The New Center And The Intellectualism Of St. Thomas, Printed in the United States of America Vernon J. -

New Books for December 2019 Grace, Predestination, and the Permission of Sin: a Thomistic Analysis by O'neill, Taylor Patrick, A

New Books for December 2019 Grace, predestination, and the permission of sin: a Thomistic analysis by O'Neill, Taylor Patrick, author. Book B765.T54 O56 2019 Faith and the founders of the American republic Book BL2525 .F325 2014 Moral combat: how sex divided American Christians and fractured American politics by Griffith, R. Marie 1967- author. (Ruth Marie), Book BR516 .G75 2017 Southern religion and Christian diversity in the twentieth century by Flynt, Wayne, 1940- author. Book BR535 .F59 2016 The story of Latino Protestants in the United States by Martínez, Juan Francisco, 1957- author. Book BR563.H57 M362 2018 The land of Israel in the Book of Ezekiel by Pikor, Wojciech, Book BS1199.L28 P55 2018 2 Kings by Park, Song-Mi Suzie, author. Book BS1335.53 .P37 2019 The Parables in Q by Roth, Dieter T., author. Book BS2555.52 .R68 2018 Hearing Revelation 1-3: listening with Greek rhetoric and culture by Neyrey, Jerome H., 1940- author. Book BS2825.52 .N495 2019 "Your God is a devouring fire": fire as a motif of divine presence and agency in the Hebrew Bible by Simone, Michael R., 1972- author. Book BS680.F53 S56 2019 Trinitarian and cosmotheandric vision by Panikkar, Raimon, Book BT111.3 .P36 2019 The life of Jesus: a graphic novel by Alex, Ben, author. Book BT302 .M66 2017 Our Lady of Guadalupe: the graphic novel by Muglia, Natalie, Book BT660.G8 M84 2018 An ecological theology of liberation: salvation and political ecology by Castillo, Daniel Patrick, author. Book BT83.57 .C365 2019 The Satan: how God's executioner became the enemy by Stokes, Ryan E., Book BT982 .S76 2019 Lectio Divina of the Gospels: for the liturgical year 2019-2020. -

The Pre-History of Subsidiarity in Leo XIII

Journal of Catholic Legal Studies Volume 56 Number 1 Article 5 The Pre-History of Subsidiarity in Leo XIII Michael P. Moreland Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcls This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Catholic Legal Studies by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FINAL_MORELAND 8/14/2018 9:10 PM THE PRE-HISTORY OF SUBSIDIARITY IN LEO XIII MICHAEL P. MORELAND† Christian Legal Thought is a much-anticipated contribution from Patrick Brennan and William Brewbaker that brings the resources of the Christian intellectual tradition to bear on law and legal education. Among its many strengths, the book deftly combines Catholic and Protestant contributions and scholarly material with more widely accessible sources such as sermons and newspaper columns. But no project aiming at a crisp and manageably-sized presentation of Christianity’s contribution to law could hope to offer a comprehensive treatment of particular themes. And so, in this brief essay, I seek to elaborate upon the treatment of the principle of subsidiarity in Catholic social thought. Subsidiarity is mentioned a handful of times in Christian Legal Thought, most squarely with a lengthy quotation from Pius XI’s articulation of the principle in Quadragesimo Anno.1 In this proposed elaboration of subsidiarity, I wish to broaden the discussion of subsidiarity historically (back a few decades from Quadragesimo Anno to the pontificate of Leo XIII) and philosophically (most especially its relation to Leo XIII’s revival of Thomism).2 Statements of the principle have historically been terse and straightforward even if the application of subsidiarity to particular legal questions has not. -

Gen Assembly Report Extended V1

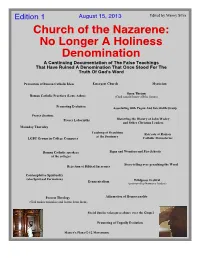

Edition 1 August 15, 2013 Edited by Manny Silva Church of the Nazarene: No Longer A Holiness Denomination A Continuing Documentation of The False Teachings That Have Ruined A Denomination That Once Stood For The Truth Of God's Word Promotion of Roman Catholic Ideas Emergent Church Mysticism Open Theism Roman Catholic Practices (Lent, Ashes) (God cannot know all the future) Promoting Evolution Associating with Pagan And Interfaith Group Prayer Stations Prayer Labyrinths Distorting the History of John Wesley and Other Christian Leaders Maunday Thursday Teaching of Occultism Retreats at Roman at the Seminary LGBT Groups in College Campuses Catholic Monasteries Roman Catholic speakers Signs and Wonders and Fire Schools at the colleges Story-telling over preaching the Word Rejection of Biblical Inerrancy Contemplative Spirituality (aka Spiritual Formation) Ecumenicalism Wildgoose Festival (promoted by Nazarene leaders) Process Theology Affirmation of Homosexuality (God makes mistakes and learns from them) Social Justice takes precedence over the Gospel Promoting of Ungodly Evolution Master's Plan (G-12 Movement) The Church of the Nazarene: General Assembly 2013 Report, And Various Papers Documenting The Heresies In The Church [This document can be copied and distributed to others to alert them to the state of the Church of the Nazarene and its universities and colleges. This document has been compiled for the sake of the brothers and sisters in Christ in the Church of the Nazarene. It is solely driven by love for those who may be, or have been, deceived by the many false teachings and teachers that have invaded the church. I cannot explain exactly why such blatantly unbiblical and satanic teachings have fooled so many. -

MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES to MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to the College of Arts and Sciences Of

MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES TO MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Matthew Glen Minix UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio December 2016 MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES TO MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Name: Minix, Matthew G. APPROVED BY: _____________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Dissertation Director _____________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Dissertation Reader. _____________________________________ Anthony Burke Smith, Ph.D. Dissertation Reader _____________________________________ John A. Inglis, Ph.D. Dissertation Reader _____________________________________ Jack J. Bauer, Ph.D. _____________________________________ Daniel Speed Thompson, Ph.D. Chair, Department of Religious Studies ii © Copyright by Matthew Glen Minix All rights reserved 2016 iii ABSTRACT MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES TO MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Name: Minix, Matthew Glen University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. Sandra A. Yocum This dissertation considers a spectrum of five distinct approaches that mid-twentieth century neo-Thomist Catholic thinkers utilized when engaging with the tradition of modern scientific psychology: a critical approach, a reformulation approach, a synthetic approach, a particular [Jungian] approach, and a personalist approach. This work argues that mid-twentieth century neo-Thomists were essentially united in their concerns about the metaphysical principles of many modern psychologists as well as in their worries that these same modern psychologists had a tendency to overlook the transcendent dimension of human existence. This work shows that the first four neo-Thomist thinkers failed to bring the traditions of neo-Thomism and modern psychology together to the extent that they suggested purely theoretical ways of reconciling them. -

Download Article PDF , Format and Size of the File

History of humanitarian ideas The historical foundations of humanitarian action by Dr. Jean Guillermand After nearly 130 years of existence, the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement continues to play a unique and important role in the field of human relations. Its origin may be traced to the impression made on Henry Dunant, a chance witness at the scene, by the disastrous lack of medical care at the battle of Solferino in 1859 and the compassionate response aroused in the people of Lombardy by the plight of the wounded. The Movement has since gained importance and expanded to such a degree that it is now an irreplaceable institution made up of dedicated people all over the world. The Movement's success can clearly be attributed in great part to the commitment of those who carried on the pioneering work of its founders. But it is also the result of a constantly growing awareness of the conditions needed for such work to be accomplished. The initial text of the 1864 Convention was already quite explicit about its application in situations of armed conflict. Jean Pictet's analysis in 19S5 and the adoption by the Vienna Conference of the seven Fundamental Principles in 1965 have since codified in international law what was originally a generous and spontaneous impulse. In a world where the weight of hard-hitting arguments and the impact of the media play a key role in shaping public opinion, the fact that the Movement's initial spirit has survived intact and strong without having recourse to aggressive publicity campaigns or losing its independence to the political ideologies that divide the globe may well surprise an impartial observer of society today. -

The Holy See, Social Justice, and International Trade Law: Assessing the Social Mission of the Catholic Church in the Gatt-Wto System

THE HOLY SEE, SOCIAL JUSTICE, AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE LAW: ASSESSING THE SOCIAL MISSION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE GATT-WTO SYSTEM By Copyright 2014 Fr. Alphonsus Ihuoma Submitted to the graduate degree program in Law and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Juridical Science (S.J.D) ________________________________ Professor Raj Bhala (Chairperson) _______________________________ Professor Virginia Harper Ho (Member) ________________________________ Professor Uma Outka (Member) ________________________________ Richard Coll (Member) Date Defended: May 15, 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Fr. Alphonsus Ihuoma certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE HOLY SEE, SOCIAL JUSTICE, AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE LAW: ASSESSING THE SOCIAL MISSION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE GATT- WTO SYSTEM by Fr. Alphonsus Ihuoma ________________________________ Professor Raj Bhala (Chairperson) Date approved: May 15, 2014 ii ABSTRACT Man, as a person, is superior to the state, and consequently the good of the person transcends the good of the state. The philosopher Jacques Maritain developed his political philosophy thoroughly informed by his deep Catholic faith. His philosophy places the human person at the center of every action. In developing his political thought, he enumerates two principal tasks of the state as (1) to establish and preserve order, and as such, guarantee justice, and (2) to promote the common good. The state has such duties to the people because it receives its authority from the people. The people possess natural, God-given right of self-government, the exercise of which they voluntarily invest in the state. -

ABSTRACT Is “Social Justice” Justice? a Thomistic Argument For

ABSTRACT Is “Social Justice” Justice? A Thomistic Argument for “Social Persons” as the Proper Subjects of the Virtue of Social Justice John R. Lee, Ph.D. Mentor: Francis J. Beckwith, Ph.D. The term “social justice,” as it occurs in the Catholic social encyclical tradition, presents a core, definitional problem. According to Catholic social thought, social justice has social institutions as its subjects. However, in the Thomistic tradition, justice is understood to be a virtue, i.e., a human habit with human persons as subjects. Thus, with its non-personal subjects, social justice would seem not to be a virtue, and thus not to be a true form of justice. We offer a solution to this problem, based on the idea of social personhood. Drawing from the Thomistic understanding of “person” as a being “distinct in a rational nature”, it is argued that certain social institutions—those with a unity of order—are capable of meeting Aquinas’ analogical definition of personhood. Thus, social institutions with a unity of order—i.e., societies —are understood to be “social persons” and thus the proper subjects of virtue, including the virtue of justice. After a review of alternative conceptions, it is argued that “social justice” in the Catholic social encyclical tradition is best understood as general justice (justice directed toward the common good) extended to include not only human persons, but social persons as well. Advantages of this conception are highlighted. Metaphysically, an understanding of social justice as exercised by social persons fits nicely with an understanding of society as non-substantial, but subsistent being. -

Catholic Cosmopolitanism and the Future of Human Rights

religions Article Catholic Cosmopolitanism and the Future of Human Rights Leonard Taylor Department of Social Sciences, Institute of Technology, F91 YW50 Sligo, Ireland; [email protected]; Tel.: +353-71-9305887 Received: 2 October 2020; Accepted: 27 October 2020; Published: 30 October 2020 Abstract: Political Catholicism began in the 20th century by presenting a conception of confessional politics to a secularizing Europe. However, this article reveals the reworking of political Catholicism’s historical commitment to a balance of two powers—an ancient Imperium and Sacerdotium—to justify change to this position. A secular democratic faith became a key insight in political Catholicism in the 20th century, as it wedded human rights to an evolving cosmopolitan Catholicism and underlined the growth of Christian democracy. This article argues that the thesis of Christian democracy held a central post-war motif that there existed a prisca theologia or a philosophia perennis, semblances of a natural law, in secular modernity that could reshape the social compact of the modern project of democracy. However, as the Cold War ended, human rights became more secularized in keeping with trends across Europe. The relationship between political Catholicism and human rights reached a turning point, and this article asks if a cosmopolitan political Catholicism still interprets human rights as central to its embrace of the modern world. Keywords: political Catholicism; Christian democracy; human rights 1. Introduction The arrival of a cosmopolitan Catholic rights-based tradition in the early 20th century has problematized histories of human rights and political Catholicism. The history of human rights is often presented as a secular affair, while research in political Catholicism tends to steer clear of the development of international law. -

Behr University of Houston, Texas (USA)

CONGRESSO TOMISTA INTERNAZIONALE L’UMANESIMO CRISTIANO NEL III MILLENIO: PROSPETTIVA DI TOMMASO D’AQUINO ROMA, 21-25 settembre 2003 Pontificia Accademia di San Tommaso – Società Internazionale Tommaso d’Aquino Luigi Taparelli on the Dignity of Man Dr. Thomas C. Behr University of Houston, Texas (USA) The paper will present a brief overview of Luigi Taparelli’s natural law social and political philosophy which he elaborated in response to the intellectual and political crisis of his times. Influenced by both Traditionalist and Eclectic philosophical movements, Taparelli perceived already in the 1820’s, as Rector of the Collegio Romano, the pedagogical utility of returning to the principles of scholastic philosophical and theological inquiry. Taparelli built on his appreciation for the scholastic philosophers, and in particular for St. Thomas Aquinas, a Catholic natural law philosophy that could integrate what was tenable from modern social and political thought, while refuting, on both theoretical and practical grounds, its naturalistic errors. His agitation for a renewal of Thomistic philosophy within the Society of Jesus, his work on natural law, and his writings on social, political and economic topics for over 10 years at the Civiltà Cattolica, constitute an important early expression of the Thomistic idea of Christian humanism that became the central pillar of Catholic social teaching. Luigi Taparelli, S.J. (1793-1862) was an outstanding figure in the history of 19th-century Catholic social and political thought by any standard. In -

Joseph Cardinal Höffner CHRISTIAN SOCIAL TEACHING

Joseph Cardinal Höffner CHRISTIAN SOCIAL TEACHING With an Introduction and Complementary Notes by Lothar Roos Original (published in German): Joseph Kardinal Höffner CHRISTLICHE GESELLSCHAFTSLEHRE Edited, revised and supplemented by Lothar Roos Editor: Butzon & Bercker Publishing Company: Butzon & Bercker • D-47623 Kevelaer, 1997 ISBN 3-7666-0324-8 Translation and digitalization sponsored and organized by: ORDO SOCIALIS Academic Association for the Promotion of Christian Social Teaching Wissenschaftliche Vereinigung zur Förderung der Christlichen Gesellschaftslehre e.V. The members of the board are published in the impressum of www.ordosocialis.de Head Office: Georgstr. 18 • 50676 Köln (Cologne) • Germany Tel: 0049 (0)221-27237-0 • Fax: 0049 (0)221-27237-27 • E-mail: [email protected] English edition: Translation: Stephan Wentworth-Arndt, PhD; Gerald Finan (Introduction Roos and Notes) © ORDO SOCIALIS, Cologne, Germany, Second Edition 1997 Consultant: Prof. Dr. Karl H. Peschke Editorial Supervision: Dr. Johannes Stemmler Layout and Typesetting: Thomas Heider, Bergisch Gladbach Edited by ORDO SOCIALIS, published by LÚC, Bratislava ISBN 80-7114-196-8 Digitalized by Jochen Michels 2006, Layout by Dr. Clara E. Laeis The rights of publication and translation are reserved and can be granted upon request. Please contact ORDO SOCIALIS. 2 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION TO THE ENGLISH EDITION ................................................ 12 FOREWORD........................................................................................................ -

Lay People in the Asian Church

Lay People in the Asian Church: A Critical Study of the Role of the Laity in the Contextual Theology of the Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conferences (1970-2001) with Special Reference to John Paul II’s Apostolic Exhortations Christifideles Laici (1989) and Ecclesia in Asia (1999), and the Pastoral Letters of the Vietnamese Episcopal Conference Submitted by Peter Nguyen Van Hai Undergraduate Studies in Scholastic Philosophy and Theology (St. Pius X Pontifical College, Ðà Lạt, Việt Nam) Graduate Diplomas in Computing Studies, Librarianship, and Management Sciences Master of Public Administration (University of Canberra, Australia) A Thesis Submitted in Total Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Theology Faculty of Arts and Sciences Australian Catholic University Research Services Locked Bag 4115 Fitzroy, Victoria 3065 Date of Submission 20 February 2009 Statement of Sources Except where otherwise indicated, this thesis is my own original work, and has not been submitted, either in whole or in part, for any academic award at this or any other tertiary educational institution. Some of the material in this thesis has been published in the Australian E-Journal of Theology, the details of which are: Hai, Peter N.V. “Fides Quaerens Dialogum: Theological Methodologies of the Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conferences.” http://dlibrary.acu.edu.au/research/theology/ejournal/aejt_8/hai.htm (accessed 1 November 2006). Hai, Peter N.V. “Lay People in the Asian Church: A Study of John Paul II’s Theology of the Laity in Ecclesia in Asia with Reference to the Documents of the Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conferences.” http://dlibrary.acu.edu.au/research/theology/ejournal/aejt_10/hai.htm (accessed 30 May 2007).