Joseph Cardinal Höffner CHRISTIAN SOCIAL TEACHING

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One Hundred Years of Thomism Aeterni Patris and Afterwards a Symposium

One Hundred Years of Thomism Aeterni Patris and Afterwards A Symposium Edited By Victor B. Brezik, C.S.B, CENTER FOR THOMISTIC STUDIES University of St. Thomas Houston, Texas 77006 ~ NIHIL OBSTAT: ReverendJamesK. Contents Farge, C.S.B. Censor Deputatus INTRODUCTION . 1 IMPRIMATUR: LOOKING AT THE PAST . 5 Most Reverend John L. Morkovsky, S.T.D. A Remembrance Of Pope Leo XIII: The Encyclical Aeterni Patris, Leonard E. Boyle,O.P. 7 Bishop of Galveston-Houston Commentary, James A. Weisheipl, O.P. ..23 January 6, 1981 The Legacy Of Etienne Gilson, Armand A. Maurer,C.S.B . .28 The Legacy Of Jacques Maritain, Christian Philosopher, First Printing: April 1981 Donald A. Gallagher. .45 LOOKING AT THE PRESENT. .61 Copyright©1981 by The Center For Thomistic Studies Reflections On Christian Philosophy, All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or Ralph McInerny . .63 reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written Thomism And Today's Crisis In Moral Values, Michael permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in Bertram Crowe . .74 critical articles and reviews. For information, write to The Transcendental Thomism, A Critical Assessment, Center For Thomistic Studies, 3812 Montrose Boulevard, Robert J. Henle, S.J. 90 Houston, Texas 77006. LOOKING AT THE FUTURE. .117 Library of Congress catalog card number: 80-70377 Can St. Thomas Speak To The Modem World?, Leo Sweeney, S.J. .119 The Future Of Thomistic Metaphysics, ISBN 0-9605456-0-3 Joseph Owens, C.Ss.R. .142 EPILOGUE. .163 The New Center And The Intellectualism Of St. Thomas, Printed in the United States of America Vernon J. -

New Books for December 2019 Grace, Predestination, and the Permission of Sin: a Thomistic Analysis by O'neill, Taylor Patrick, A

New Books for December 2019 Grace, predestination, and the permission of sin: a Thomistic analysis by O'Neill, Taylor Patrick, author. Book B765.T54 O56 2019 Faith and the founders of the American republic Book BL2525 .F325 2014 Moral combat: how sex divided American Christians and fractured American politics by Griffith, R. Marie 1967- author. (Ruth Marie), Book BR516 .G75 2017 Southern religion and Christian diversity in the twentieth century by Flynt, Wayne, 1940- author. Book BR535 .F59 2016 The story of Latino Protestants in the United States by Martínez, Juan Francisco, 1957- author. Book BR563.H57 M362 2018 The land of Israel in the Book of Ezekiel by Pikor, Wojciech, Book BS1199.L28 P55 2018 2 Kings by Park, Song-Mi Suzie, author. Book BS1335.53 .P37 2019 The Parables in Q by Roth, Dieter T., author. Book BS2555.52 .R68 2018 Hearing Revelation 1-3: listening with Greek rhetoric and culture by Neyrey, Jerome H., 1940- author. Book BS2825.52 .N495 2019 "Your God is a devouring fire": fire as a motif of divine presence and agency in the Hebrew Bible by Simone, Michael R., 1972- author. Book BS680.F53 S56 2019 Trinitarian and cosmotheandric vision by Panikkar, Raimon, Book BT111.3 .P36 2019 The life of Jesus: a graphic novel by Alex, Ben, author. Book BT302 .M66 2017 Our Lady of Guadalupe: the graphic novel by Muglia, Natalie, Book BT660.G8 M84 2018 An ecological theology of liberation: salvation and political ecology by Castillo, Daniel Patrick, author. Book BT83.57 .C365 2019 The Satan: how God's executioner became the enemy by Stokes, Ryan E., Book BT982 .S76 2019 Lectio Divina of the Gospels: for the liturgical year 2019-2020. -

Theme 4 of Catholic Social Teaching

THEME 4 OF CATHOLIC SOCIAL TEACHING: OPTION FOR THE POOR AND VULNERABLE A basic moral test is how our most vulnerable members are faring. In a society marred by deepening divisions between rich and poor, our tradition recalls the story of the Last Judgment (Mt. 25: 31-46) and instructs us to put the needs of the poor and vulnerable first. Scripture . Exodus 22:20-26 You shall not oppress the poor or vulnerable. God will hear their cry. Leviticus 19:9-10 A portion of the harvest is set aside for the poor and the stranger. Job 34:20-28 The Lord hears the cry of the poor. Proverbs 31:8-9 Speak out in defense of the poor. Sirach 4:1-10 Don’t delay giving to those in need. Isaiah 25:4-5 God is a refuge for the poor. Isaiah 58:5-7 True worship is to work for justice and care for the poor and oppressed. Matthew 25:34-40 What you do for the least among you, you do for Jesus. Luke 4:16-21 Jesus proclaims his mission: to bring good news to the poor and oppressed. Luke 6:20-23 Blessed are the poor, theirs is the kingdom of God. 1 John 3:17-18 How does God’s love abide in anyone who has the world’s good and sees one in need and refuses to help? . 2 Corinthians 8: 7,9,13 Exhorts Christians to excel in grace of giving Tradition Still, when there is question of defending the rights of individuals, the poor and badly off have a claim to especial consideration. -

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr

High School: Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Grade: High School-- Course 2, Course 4, Course 5, Course 6, and Option C. “This is the original meaning of Doctrinal concepts: justice, where we are in right • Course 2: God creates the human person in his image and likeness; we must respect the dignity relationship with God, with one of all (CCC 1700-1709); another, and with the rest of God's • Course 4: The unity of the human race (CCC creation. Justice was a gift of grace 760, 791, 813-822); given to all of humanity." • Course 6: The natural moral law as the basis for – U.S. bishops, Open Wide Our Hearts human rights and duties (CCC 1956-1960); • Option C: Christ’s command to love one another as he has loved us (CCC 1823, 2196) Objectives Students should be able to: 1. Become familiar with Catholic Social Teaching (CST) on the life and dignity of the human person. 2. Reflect on how racism rejects the image of God present in each of us. 3. Understand how the life and witness of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. exemplifies the social engagement called for by CST. Quotes from Open Wide our Hearts • "Overcoming racism is a demand of justice, but because Christian love transcends justice, the end of racism will mean that our community will bear fruit beyond simply the fair treatment of all." High School Activity: Dr. King • "Racism is a moral problem that requires a moral remedy—a transformation of the human heart—that impels us to act. -

The Pre-History of Subsidiarity in Leo XIII

Journal of Catholic Legal Studies Volume 56 Number 1 Article 5 The Pre-History of Subsidiarity in Leo XIII Michael P. Moreland Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcls This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Catholic Legal Studies by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FINAL_MORELAND 8/14/2018 9:10 PM THE PRE-HISTORY OF SUBSIDIARITY IN LEO XIII MICHAEL P. MORELAND† Christian Legal Thought is a much-anticipated contribution from Patrick Brennan and William Brewbaker that brings the resources of the Christian intellectual tradition to bear on law and legal education. Among its many strengths, the book deftly combines Catholic and Protestant contributions and scholarly material with more widely accessible sources such as sermons and newspaper columns. But no project aiming at a crisp and manageably-sized presentation of Christianity’s contribution to law could hope to offer a comprehensive treatment of particular themes. And so, in this brief essay, I seek to elaborate upon the treatment of the principle of subsidiarity in Catholic social thought. Subsidiarity is mentioned a handful of times in Christian Legal Thought, most squarely with a lengthy quotation from Pius XI’s articulation of the principle in Quadragesimo Anno.1 In this proposed elaboration of subsidiarity, I wish to broaden the discussion of subsidiarity historically (back a few decades from Quadragesimo Anno to the pontificate of Leo XIII) and philosophically (most especially its relation to Leo XIII’s revival of Thomism).2 Statements of the principle have historically been terse and straightforward even if the application of subsidiarity to particular legal questions has not. -

Catholic Social Teaching and Sustainable Development: What the Church Provides for Specialists

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 8-19-2020 Catholic Social Teaching and Sustainable Development: What the Church Provides for Specialists Anthony Philip Stine Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Ethics in Religion Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Public Affairs Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Stine, Anthony Philip, "Catholic Social Teaching and Sustainable Development: What the Church Provides for Specialists" (2020). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 5604. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.7476 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Catholic Social Teaching and Sustainable Development: What the Church Provides for Specialists by Anthony Philip Stine A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public Affairs and Policy Dissertation Committee: Christopher Shortell, Chair Kent Robinson Jennifer Allen Daniel Jaffee Portland State University 2020 © 2020 Anthony Philip Stine Abstract The principles of Catholic Social Teaching as represented by the writings of 150 years of popes as well as the theorists inspired by those writings are examined, as well as the two principal schools of thought in the sustainability literature as represented by what is classically called the anthropocentric or managerial approach to sustainability as well as the biocentric school of thought. This study extends previous research by analyzing what the Catholic Church has said over the course of centuries on issues related to society, economics, and the environment, as embodied in the core concepts of subsidiarity, solidarity, stewardship, the common good, and integral human development. -

Distributism Debate

The Distributism Debate The Distributism Debate Dane J. Weber Donald P. Goodman III Eds. GP Goretti Publications Dozenal numeration is a system of thinking of numbers in twelves, rather than tens. Twelve is much more versatile, having four even divisors—2, 3, 4, and 6—as opposed to only two for ten. This means that such hatefulness as “0.333. ” for 1/3 and “0.1666. ” for 1/6 are things of the past, replaced by easy “0;4” (four twelfths) and “0;2” (two twelfths). In dozenal, counting goes “one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten, elv, dozen; dozen one, dozen two, dozen three, dozen four, dozen five, dozen six, dozen seven, dozen eight, dozen nine, dozen ten, dozen elv, two dozen, two dozen one. ” It’s written as such: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, X, E, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 1X, 1E, 20, 21... Dozenal counting is at once much more efficient and much easier than decimal counting, and takes only a little bit of time to get used to. Further information can be had from the dozenal societies (http:// www.dozenal.org), as well as in many other places on the Internet. © 2006 (11E2) Dane J. Weber and Donald P. Goodman III, Version 3.0. All rights reserved. This document may be copied and distributed freely, provided that it is done in its entirety, including this copyright page, and is not modified in any way. Goretti Publications http://gorpub.freeshell.org [email protected] No copyright on this work is intended to in any way derogate from the copyright holders of any individual part of this work. -

Gen Assembly Report Extended V1

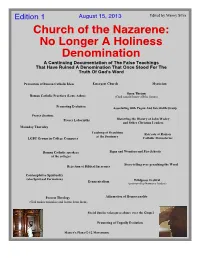

Edition 1 August 15, 2013 Edited by Manny Silva Church of the Nazarene: No Longer A Holiness Denomination A Continuing Documentation of The False Teachings That Have Ruined A Denomination That Once Stood For The Truth Of God's Word Promotion of Roman Catholic Ideas Emergent Church Mysticism Open Theism Roman Catholic Practices (Lent, Ashes) (God cannot know all the future) Promoting Evolution Associating with Pagan And Interfaith Group Prayer Stations Prayer Labyrinths Distorting the History of John Wesley and Other Christian Leaders Maunday Thursday Teaching of Occultism Retreats at Roman at the Seminary LGBT Groups in College Campuses Catholic Monasteries Roman Catholic speakers Signs and Wonders and Fire Schools at the colleges Story-telling over preaching the Word Rejection of Biblical Inerrancy Contemplative Spirituality (aka Spiritual Formation) Ecumenicalism Wildgoose Festival (promoted by Nazarene leaders) Process Theology Affirmation of Homosexuality (God makes mistakes and learns from them) Social Justice takes precedence over the Gospel Promoting of Ungodly Evolution Master's Plan (G-12 Movement) The Church of the Nazarene: General Assembly 2013 Report, And Various Papers Documenting The Heresies In The Church [This document can be copied and distributed to others to alert them to the state of the Church of the Nazarene and its universities and colleges. This document has been compiled for the sake of the brothers and sisters in Christ in the Church of the Nazarene. It is solely driven by love for those who may be, or have been, deceived by the many false teachings and teachers that have invaded the church. I cannot explain exactly why such blatantly unbiblical and satanic teachings have fooled so many. -

Dignitatis Humanae and the Development of Moral Doctrine: Assessing Change in Catholic Social Teaching on Religious Liberty

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA Dignitatis humanae and the Development of Moral Doctrine: Assessing Change in Catholic Social Teaching on Religious Liberty A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By Barrett Hamilton Turner Washington, D.C 2015 Dignitatis humanae and the Development of Moral Doctrine: Assessing Change in Catholic Social Teaching on Religious Liberty Barrett Hamilton Turner, Ph.D. Director: Joseph E. Capizzi, Ph.D. Vatican II’s Declaration on Religious Liberty, Dignitatis humanae (DH), poses the problem of development in Catholic moral and social doctrine. This problem is threefold, consisting in properly understanding the meaning of pre-conciliar magisterial teaching on religious liberty, the meaning of DH itself, and the Declaration’s implications for how social doctrine develops. A survey of recent scholarship reveals that scholars attend to the first two elements in contradictory ways, and that their accounts of doctrinal development are vague. The dissertation then proceeds to the threefold problematic. Chapter two outlines the general parameters of doctrinal development. The third chapter gives an interpretation of the pre- conciliar teaching from Pius IX to John XXIII. To better determine the meaning of DH, the fourth chapter examines the Declaration’s drafts and the official explanatory speeches (relationes) contained in Vatican II’s Acta synodalia. The fifth chapter discusses how experience may contribute to doctrinal development and proposes an explanation for how the doctrine on religious liberty changed, drawing upon the work of Jacques Maritain and Basile Valuet. -

MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES to MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to the College of Arts and Sciences Of

MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES TO MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Matthew Glen Minix UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio December 2016 MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES TO MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Name: Minix, Matthew G. APPROVED BY: _____________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Dissertation Director _____________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Dissertation Reader. _____________________________________ Anthony Burke Smith, Ph.D. Dissertation Reader _____________________________________ John A. Inglis, Ph.D. Dissertation Reader _____________________________________ Jack J. Bauer, Ph.D. _____________________________________ Daniel Speed Thompson, Ph.D. Chair, Department of Religious Studies ii © Copyright by Matthew Glen Minix All rights reserved 2016 iii ABSTRACT MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES TO MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Name: Minix, Matthew Glen University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. Sandra A. Yocum This dissertation considers a spectrum of five distinct approaches that mid-twentieth century neo-Thomist Catholic thinkers utilized when engaging with the tradition of modern scientific psychology: a critical approach, a reformulation approach, a synthetic approach, a particular [Jungian] approach, and a personalist approach. This work argues that mid-twentieth century neo-Thomists were essentially united in their concerns about the metaphysical principles of many modern psychologists as well as in their worries that these same modern psychologists had a tendency to overlook the transcendent dimension of human existence. This work shows that the first four neo-Thomist thinkers failed to bring the traditions of neo-Thomism and modern psychology together to the extent that they suggested purely theoretical ways of reconciling them. -

Catholicism: Catholic Social Thought

Boston College—Office of University Mission and Ministry Catholicism: Catholic Social Thought Exploring the Jesuit and Catholic dimensions of the university's mission One of the best resources for exploring Catholic social thought is the web site of the Office of Social Justice of the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis. It lists the major documents from popes, Vatican offices, and the American Catholic bishops’ conference and provides links to the text of most of them (in Spanish as well) along with notable quotations, a concordance, and a bibliography for each. It digests ten major themes or principles in Catholic social thought and provides one-page and two-page summaries of each. It offers reading lists and a toolbox for teachers. Here is a sample of the web site’s accessible style, which also nicely introduces the whole topic: There is a broad and a narrow understanding to the expression Catholic social teaching. Viewed one way, Catholic social teaching (hereafter CST) encompasses all the ideas and theories that have developed over the entire history of the Church on matters of social life. More commonly, as the term has come to be understood, CST refers to a limited body of literature written in the modern era that is a response of papal and episcopal teachers to the various political, economic and social issues of our time. Even this more narrow understanding, however, is not neatly defined. No official list of documents exists; it is more a matter of general consensus which documents fall into the category of CST. Some documents, for example Rerum Novarum (an encyclical letter by Leo XIII) are on everyone’s list while the Christmas radio addresses of Pius XII are cited by some but not all as part of the heritage. -

Catholic Social Teaching: a Tradition Through Quotes

Catholic Social Teaching: A Tradition through Quotes "When I fed the poor, they called me a saint. When I asked why the poor had no food, they called me a Communist." —Archbishop Dom Hélder Câmara "If you want peace, work for justice." —Blessed Paul VI "Justice comes before charity." —St. John XXIII "Peace is not the product of terror or fear. Peace is not the silence of cemeteries. Peace is not the silent result of violent repression. Peace is the generous, tranquil contribution of all to the good of all. Peace is dynamism. Peace is generosity. It is right and it is duty." —Archbishop Óscar Romero "Peace is not merely the absence of war; nor can it be reduced solely to the maintenance of a balance of power between enemies; nor is it brought about by dictatorship. Instead, it is rightly and appropriately called an enterprise of justice." —The Bishops of the Second Vatican Council “[Catholics can] in no way convince themselves that so enormous and unjust an inequality in the distribution of this world's goods truly conforms to the designs of the all-wise Creator." —Pope Pius XI “Miss no single opportunity of making some small sacrifice, here by a smiling look, there by a kindly word; always doing the smallest things right, and doing all for love.” —St. Thérèse of Lisieux “The bread you store up belongs to the hungry; the cloak that lies in your chest belongs to the naked; the gold you have hidden in the ground belongs to the poor.” –St. Basil the Great “Do not grieve or complain that you were born in a time when you can no longer see God in the flesh.