Download Article PDF , Format and Size of the File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One Hundred Years of Thomism Aeterni Patris and Afterwards a Symposium

One Hundred Years of Thomism Aeterni Patris and Afterwards A Symposium Edited By Victor B. Brezik, C.S.B, CENTER FOR THOMISTIC STUDIES University of St. Thomas Houston, Texas 77006 ~ NIHIL OBSTAT: ReverendJamesK. Contents Farge, C.S.B. Censor Deputatus INTRODUCTION . 1 IMPRIMATUR: LOOKING AT THE PAST . 5 Most Reverend John L. Morkovsky, S.T.D. A Remembrance Of Pope Leo XIII: The Encyclical Aeterni Patris, Leonard E. Boyle,O.P. 7 Bishop of Galveston-Houston Commentary, James A. Weisheipl, O.P. ..23 January 6, 1981 The Legacy Of Etienne Gilson, Armand A. Maurer,C.S.B . .28 The Legacy Of Jacques Maritain, Christian Philosopher, First Printing: April 1981 Donald A. Gallagher. .45 LOOKING AT THE PRESENT. .61 Copyright©1981 by The Center For Thomistic Studies Reflections On Christian Philosophy, All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or Ralph McInerny . .63 reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written Thomism And Today's Crisis In Moral Values, Michael permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in Bertram Crowe . .74 critical articles and reviews. For information, write to The Transcendental Thomism, A Critical Assessment, Center For Thomistic Studies, 3812 Montrose Boulevard, Robert J. Henle, S.J. 90 Houston, Texas 77006. LOOKING AT THE FUTURE. .117 Library of Congress catalog card number: 80-70377 Can St. Thomas Speak To The Modem World?, Leo Sweeney, S.J. .119 The Future Of Thomistic Metaphysics, ISBN 0-9605456-0-3 Joseph Owens, C.Ss.R. .142 EPILOGUE. .163 The New Center And The Intellectualism Of St. Thomas, Printed in the United States of America Vernon J. -

New Books for December 2019 Grace, Predestination, and the Permission of Sin: a Thomistic Analysis by O'neill, Taylor Patrick, A

New Books for December 2019 Grace, predestination, and the permission of sin: a Thomistic analysis by O'Neill, Taylor Patrick, author. Book B765.T54 O56 2019 Faith and the founders of the American republic Book BL2525 .F325 2014 Moral combat: how sex divided American Christians and fractured American politics by Griffith, R. Marie 1967- author. (Ruth Marie), Book BR516 .G75 2017 Southern religion and Christian diversity in the twentieth century by Flynt, Wayne, 1940- author. Book BR535 .F59 2016 The story of Latino Protestants in the United States by Martínez, Juan Francisco, 1957- author. Book BR563.H57 M362 2018 The land of Israel in the Book of Ezekiel by Pikor, Wojciech, Book BS1199.L28 P55 2018 2 Kings by Park, Song-Mi Suzie, author. Book BS1335.53 .P37 2019 The Parables in Q by Roth, Dieter T., author. Book BS2555.52 .R68 2018 Hearing Revelation 1-3: listening with Greek rhetoric and culture by Neyrey, Jerome H., 1940- author. Book BS2825.52 .N495 2019 "Your God is a devouring fire": fire as a motif of divine presence and agency in the Hebrew Bible by Simone, Michael R., 1972- author. Book BS680.F53 S56 2019 Trinitarian and cosmotheandric vision by Panikkar, Raimon, Book BT111.3 .P36 2019 The life of Jesus: a graphic novel by Alex, Ben, author. Book BT302 .M66 2017 Our Lady of Guadalupe: the graphic novel by Muglia, Natalie, Book BT660.G8 M84 2018 An ecological theology of liberation: salvation and political ecology by Castillo, Daniel Patrick, author. Book BT83.57 .C365 2019 The Satan: how God's executioner became the enemy by Stokes, Ryan E., Book BT982 .S76 2019 Lectio Divina of the Gospels: for the liturgical year 2019-2020. -

Colonization of the «Indies». the Origin of International Law?

LA IDEA DE AMERICA 25/10/10 12:15 Página 43 COLONIZATION OF THE «INDIES» THE ORIGIN OF INTERNATIONAL LAW? MARTTI KOSKENNIEMI It is widely agreed that international law has its origins in the writings of the Spanish theologians of the 16th century, especially the so-called «School of Sala- manca», who were reacting to the news of Columbus having found not only a new continent but a new population, living in conditions unknown to Europeans and having never heard the gospel. The name of Francisco de Vitoria (c. 1492- 1546) the Dominican scholar who taught as Prima Professor with the theology fa- culty at the University of Salamanca from 1526 to 1546, is well-known to interna- tional law historians. This was not always the case. For a long time, international lawyers used to draw their pedigree from the Dutch Protestant Hugo de Groot (or Grotius) (1583-1645) who wrote as advocate of the Dutch East-India company in favour of opening the seas to Dutch commerce against the Spanish-Portuguese monopoly. Still in the 18th and 19th centuries, the law of nations —ius gentium— was seen as a predominantly Protestant discipline that drew its inspiration from the natural law taught by such followers of Grotius as the Saxon Samuel Pufen- dorf (1632-1694) and the Swiss Huguenot Emer de Vattel (1714-1767), followed by a series of professors at 18th century German universities1. It was only towards the late-19th century when the Belgian legal historian Er- nest Nys pointed to the Catholic renewal of natural law during the Spanish siglo de oro that attention was directed to Vitoria and some of his successors, especially the Jesuit Francisco Suárez, (1548-1617), who had indeed developed a universally applicable legal vocabulary —something that late— 19th century jurists, including Nys himself, were trying to achieve2. -

Francisco De Vitoria on the Ius Gentium and the American Indios

Copright © 2012 Ave Maria Law Review FRANCISCO DE VITORIA ON THE IUS GENTIUM AND THE AMERICAN INDIOS Victor M. Salas, Jr., Ph.D. g INTRODUCTION In reading through the relections1 of Francisco de Vitoria (c. 1483– 1546), one easily conjures up the image of an author who is quintessentially Scholastic—an even-tempered and dispassionate intellectual who treats all questions with equanimity and is swayed only by the exigencies of reason itself.2 Yet, in a letter sent to his religious superior that addresses the Spanish confiscation of Peruvian property, a clearly disgusted and horrified Vitoria reacts passionately against the Spaniards’ actions and urges his superior, Miguel de Arcos, O.P., to have nothing to do with the matter. The calm and serene mood characteristic of Vitoria’s relections is replaced with fury and outrage. “I must tell you, after a lifetime of studies and long experience,” the Dominican writes, “that no business shocks me or embarrasses me more than the corrupt profits and affairs of the Indies. Their very mention freezes the blood in my veins.”3 Registering his contempt of the situation in the New World, Vitoria came to the defense of the American Indians in the only way he could, as a g Victor Salas received a Ph.D. in philosophy from Saint Louis University. He has special research interests in medieval and renaissance philosophy. Thanks are due to Robert Fastiggi for his kind invitation to present this Article at the “The Foundation of Human Rights: Catholic Contributions Conference” held at Ave Maria University, March 3–4, 2011. -

Legal Imagination in Vitoria : the Power of Ideas

Legal Imagination in Vitoria. The Power of Ideas Pablo Zapatero* Professor of Public International Law, Carlos III University, Madrid, Spain 1. A Man’s Ideas Legal progress is often propelled by concepts first envisioned in academia. In this light, the present article explores the ideas of a fascinating intellectual figure: Francisco de Vitoria (1483-1546),1 a man broadly recognized as one of the “founding fathers” of international law. The writings and lectures of this 16th century Dominican friar formulated innovative legal doctrines in an age of uncertainty and profound social change; an age that gave birth to the modern States that, with their centralized power, signalled the demise of medieval pluralism, the dismemberment of Christendom, and the erosion of imperial and papal aspirations to universal power. Medieval Europe, before then, had defined itself as a cultural, political and religious unity: the Res Publica Christiana. The first half of the 16th century witnessed the final breakdown of that order, the emergence of the modern sovereign state and the subsequent development of the European state system. It was also in this age that a singular event transformed con- ventional conceptions of the world and consolidated anthropocentrism: the discovery of America.2 A ‘stellar moment’ of literature, political and legal * For correspondence use [email protected]. Unless otherwise indicated, translations in this paper are by the author. 1) See Getino, L.G. El Maestro Fr. Francisco de Vitoria: Su vida, su doctrina e influencia, Imprenta Católica, 1930 and de Heredia, Beltrán. Francisco de Vitoria, Editorial Labor, 1939. 2) Pérez Luño, A. -

The Pre-History of Subsidiarity in Leo XIII

Journal of Catholic Legal Studies Volume 56 Number 1 Article 5 The Pre-History of Subsidiarity in Leo XIII Michael P. Moreland Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcls This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Catholic Legal Studies by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FINAL_MORELAND 8/14/2018 9:10 PM THE PRE-HISTORY OF SUBSIDIARITY IN LEO XIII MICHAEL P. MORELAND† Christian Legal Thought is a much-anticipated contribution from Patrick Brennan and William Brewbaker that brings the resources of the Christian intellectual tradition to bear on law and legal education. Among its many strengths, the book deftly combines Catholic and Protestant contributions and scholarly material with more widely accessible sources such as sermons and newspaper columns. But no project aiming at a crisp and manageably-sized presentation of Christianity’s contribution to law could hope to offer a comprehensive treatment of particular themes. And so, in this brief essay, I seek to elaborate upon the treatment of the principle of subsidiarity in Catholic social thought. Subsidiarity is mentioned a handful of times in Christian Legal Thought, most squarely with a lengthy quotation from Pius XI’s articulation of the principle in Quadragesimo Anno.1 In this proposed elaboration of subsidiarity, I wish to broaden the discussion of subsidiarity historically (back a few decades from Quadragesimo Anno to the pontificate of Leo XIII) and philosophically (most especially its relation to Leo XIII’s revival of Thomism).2 Statements of the principle have historically been terse and straightforward even if the application of subsidiarity to particular legal questions has not. -

FRANCISCO DE VITORIA, De Indis (1532) 15. Sixth Proposition

FRANCISCO DE VITORIA, De Indis (1532) 15. Sixth proposition: Although the Christian faith may have been announced to the Indians with adequate demonstration and they have refused to receive it, yet this is not a reason which justifies making war on them and depriving them of their property. This conclusion is definitely stated by St. Thomas (Secunda Secundae, qu. 10, art. 8), where he says that unbelievers who have never received the faith, like Gentiles and Jews, are in no wise to be compelled to do so. This is the received conclusion of the doctors alike in the canon law and the civil law. The proof lies in the fact that belief is an operation of the will. Now, fear detracts greatly from the voluntary (Ethics, bk. 3), and it is a sacrilege to approach under the influence of servile fear as far as the mysteries and sacraments of Christ. Our proposition receives further proof from the use and custom of the Church. For never have Christian Emperors, who had as advisors the most holy and wise Pontiffs, made war on unbelievers for their refusal to accept the Christian religion. Further, war is no argument for the truth of the Christian faith. Therefore the Indians cannot be induced by war to believe, but rather to feign belief and reception of the Christian faith, which is monstrous and a sacrilege. And although Scotus (Bk. 4, dist. 4, last qu.) calls it a religious act for princes to compel unbelievers by threats and fears to receive the faith, yet he seems to mean this to apply only to unbelievers who in other respects are subjects of Christian princes (with whom we will deal later on). -

Gen Assembly Report Extended V1

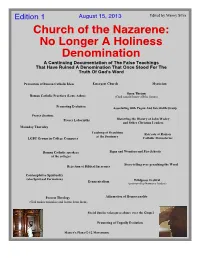

Edition 1 August 15, 2013 Edited by Manny Silva Church of the Nazarene: No Longer A Holiness Denomination A Continuing Documentation of The False Teachings That Have Ruined A Denomination That Once Stood For The Truth Of God's Word Promotion of Roman Catholic Ideas Emergent Church Mysticism Open Theism Roman Catholic Practices (Lent, Ashes) (God cannot know all the future) Promoting Evolution Associating with Pagan And Interfaith Group Prayer Stations Prayer Labyrinths Distorting the History of John Wesley and Other Christian Leaders Maunday Thursday Teaching of Occultism Retreats at Roman at the Seminary LGBT Groups in College Campuses Catholic Monasteries Roman Catholic speakers Signs and Wonders and Fire Schools at the colleges Story-telling over preaching the Word Rejection of Biblical Inerrancy Contemplative Spirituality (aka Spiritual Formation) Ecumenicalism Wildgoose Festival (promoted by Nazarene leaders) Process Theology Affirmation of Homosexuality (God makes mistakes and learns from them) Social Justice takes precedence over the Gospel Promoting of Ungodly Evolution Master's Plan (G-12 Movement) The Church of the Nazarene: General Assembly 2013 Report, And Various Papers Documenting The Heresies In The Church [This document can be copied and distributed to others to alert them to the state of the Church of the Nazarene and its universities and colleges. This document has been compiled for the sake of the brothers and sisters in Christ in the Church of the Nazarene. It is solely driven by love for those who may be, or have been, deceived by the many false teachings and teachers that have invaded the church. I cannot explain exactly why such blatantly unbiblical and satanic teachings have fooled so many. -

MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES to MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to the College of Arts and Sciences Of

MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES TO MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Matthew Glen Minix UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio December 2016 MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES TO MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Name: Minix, Matthew G. APPROVED BY: _____________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Dissertation Director _____________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Dissertation Reader. _____________________________________ Anthony Burke Smith, Ph.D. Dissertation Reader _____________________________________ John A. Inglis, Ph.D. Dissertation Reader _____________________________________ Jack J. Bauer, Ph.D. _____________________________________ Daniel Speed Thompson, Ph.D. Chair, Department of Religious Studies ii © Copyright by Matthew Glen Minix All rights reserved 2016 iii ABSTRACT MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES TO MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Name: Minix, Matthew Glen University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. Sandra A. Yocum This dissertation considers a spectrum of five distinct approaches that mid-twentieth century neo-Thomist Catholic thinkers utilized when engaging with the tradition of modern scientific psychology: a critical approach, a reformulation approach, a synthetic approach, a particular [Jungian] approach, and a personalist approach. This work argues that mid-twentieth century neo-Thomists were essentially united in their concerns about the metaphysical principles of many modern psychologists as well as in their worries that these same modern psychologists had a tendency to overlook the transcendent dimension of human existence. This work shows that the first four neo-Thomist thinkers failed to bring the traditions of neo-Thomism and modern psychology together to the extent that they suggested purely theoretical ways of reconciling them. -

Perceptions of the Influence of Francisco De Vitoria on the Development of International Law in 21St Century Discourse

Perceptions of the Influence of Francisco de Vitoria on the Development of International Law in 21st Century discourse Gerrit Altena U1274635 October 2020 Tilburg Law School Supervisor: Dr. Inge van Hulle Contents: Chapter 1: Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………………2 Chapter 2: Francisco de Vitoria and the Development of Humanitarian Intervention……………9 Chapter 3: Francisco de Vitoria and the Secularization of International Law…………….………...21 Chapter 4: Francisco de Vitoria as the Founder of International Law……………………………….....27 Chapter 5: Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………………………….37 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………………................................43 1 Chapter 1: Introduction The work of Francisco de Vitoria has always evoked conversation. Pufendorf and Kant could not agree on whether the work of the 16th Century Spanish clergyman and lecturer represented a defence or an attack on the native population of the Americas. Their disagreement has carried forth until this day.1 The conversation received renewed attention at the turn of the 20th Century, when American jurist James Brown Scott proclaimed Vitoria to be the founder of international law, as opposed to Hugo Grotius.2 Who was Francisco de Vitoria? Not much is known with certainty about the early life of Francisco de Vitoria. There is even disagreement over both Vitoria’s birthplace and the year of his birth. The former is said to be either Vitoria, the modern-day capital of Basque country, or Burgos.3 With regards to the year of his birth, there used to be a consensus on 1492. Vitoria, however, became a deacon in 1507, which would mean he would be 15 years old at that time. According to Hernández, it was impossible at the time to be a deacon at that age. -

On Preaching the Gospel to People Like the American Indians

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 15, Issue 4 1991 Article 1 Francisco Suarez:´ On Preaching the Gospel to People Like the American Indians John P. Doyle∗ ∗ Copyright c 1991 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Francisco Suarez:´ On Preaching the Gospel to People Like the American Indians John P. Doyle Abstract In this Article, I will trace Suarez’s´ thoughts on the natural equality of all men as well as the natural character and equality of their republics. Then, in a context of natural law and the limits of state power, I will consider Suarez’s´ positions on the jus gentium (law of nations) and war. Next, I will consider Suarez’s´ divisions of non-Christians and his views on preaching the Gospel to people like the American Indians. ARTICLES FRANCISCO SUAREZ: ON PREACHING THE GOSPEL TO PEOPLE LIKE THE AMERICAN INDIANS John P. Doyle* INTRODUCTION * * As is well known, the century following Columbus's dis- covery of the New World was, for Spain, El Siglo de Oro (The Century of Gold). The appellation was well deserved. In just about every area, Spain led the way. Politically, first with the Catholic sovereigns Ferdinand and Isabella, and then with the Habsburg monarchies of the Emperor Charles V (1516-1556) and his son King Philip II (1556-1598), Spanish hegemony was at its zenith.' For most of the century, Spain's military might in Western Europe was unequalled. Its ability to project that might across thousands of sea-miles to the Americas, the Phil- ippine Islands, and the Far East was astonishing even as we contemplate it today. -

The Holy See, Social Justice, and International Trade Law: Assessing the Social Mission of the Catholic Church in the Gatt-Wto System

THE HOLY SEE, SOCIAL JUSTICE, AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE LAW: ASSESSING THE SOCIAL MISSION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE GATT-WTO SYSTEM By Copyright 2014 Fr. Alphonsus Ihuoma Submitted to the graduate degree program in Law and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Juridical Science (S.J.D) ________________________________ Professor Raj Bhala (Chairperson) _______________________________ Professor Virginia Harper Ho (Member) ________________________________ Professor Uma Outka (Member) ________________________________ Richard Coll (Member) Date Defended: May 15, 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Fr. Alphonsus Ihuoma certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE HOLY SEE, SOCIAL JUSTICE, AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE LAW: ASSESSING THE SOCIAL MISSION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE GATT- WTO SYSTEM by Fr. Alphonsus Ihuoma ________________________________ Professor Raj Bhala (Chairperson) Date approved: May 15, 2014 ii ABSTRACT Man, as a person, is superior to the state, and consequently the good of the person transcends the good of the state. The philosopher Jacques Maritain developed his political philosophy thoroughly informed by his deep Catholic faith. His philosophy places the human person at the center of every action. In developing his political thought, he enumerates two principal tasks of the state as (1) to establish and preserve order, and as such, guarantee justice, and (2) to promote the common good. The state has such duties to the people because it receives its authority from the people. The people possess natural, God-given right of self-government, the exercise of which they voluntarily invest in the state.