Catholic Cosmopolitanism and the Future of Human Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One Hundred Years of Thomism Aeterni Patris and Afterwards a Symposium

One Hundred Years of Thomism Aeterni Patris and Afterwards A Symposium Edited By Victor B. Brezik, C.S.B, CENTER FOR THOMISTIC STUDIES University of St. Thomas Houston, Texas 77006 ~ NIHIL OBSTAT: ReverendJamesK. Contents Farge, C.S.B. Censor Deputatus INTRODUCTION . 1 IMPRIMATUR: LOOKING AT THE PAST . 5 Most Reverend John L. Morkovsky, S.T.D. A Remembrance Of Pope Leo XIII: The Encyclical Aeterni Patris, Leonard E. Boyle,O.P. 7 Bishop of Galveston-Houston Commentary, James A. Weisheipl, O.P. ..23 January 6, 1981 The Legacy Of Etienne Gilson, Armand A. Maurer,C.S.B . .28 The Legacy Of Jacques Maritain, Christian Philosopher, First Printing: April 1981 Donald A. Gallagher. .45 LOOKING AT THE PRESENT. .61 Copyright©1981 by The Center For Thomistic Studies Reflections On Christian Philosophy, All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or Ralph McInerny . .63 reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written Thomism And Today's Crisis In Moral Values, Michael permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in Bertram Crowe . .74 critical articles and reviews. For information, write to The Transcendental Thomism, A Critical Assessment, Center For Thomistic Studies, 3812 Montrose Boulevard, Robert J. Henle, S.J. 90 Houston, Texas 77006. LOOKING AT THE FUTURE. .117 Library of Congress catalog card number: 80-70377 Can St. Thomas Speak To The Modem World?, Leo Sweeney, S.J. .119 The Future Of Thomistic Metaphysics, ISBN 0-9605456-0-3 Joseph Owens, C.Ss.R. .142 EPILOGUE. .163 The New Center And The Intellectualism Of St. Thomas, Printed in the United States of America Vernon J. -

New Books for December 2019 Grace, Predestination, and the Permission of Sin: a Thomistic Analysis by O'neill, Taylor Patrick, A

New Books for December 2019 Grace, predestination, and the permission of sin: a Thomistic analysis by O'Neill, Taylor Patrick, author. Book B765.T54 O56 2019 Faith and the founders of the American republic Book BL2525 .F325 2014 Moral combat: how sex divided American Christians and fractured American politics by Griffith, R. Marie 1967- author. (Ruth Marie), Book BR516 .G75 2017 Southern religion and Christian diversity in the twentieth century by Flynt, Wayne, 1940- author. Book BR535 .F59 2016 The story of Latino Protestants in the United States by Martínez, Juan Francisco, 1957- author. Book BR563.H57 M362 2018 The land of Israel in the Book of Ezekiel by Pikor, Wojciech, Book BS1199.L28 P55 2018 2 Kings by Park, Song-Mi Suzie, author. Book BS1335.53 .P37 2019 The Parables in Q by Roth, Dieter T., author. Book BS2555.52 .R68 2018 Hearing Revelation 1-3: listening with Greek rhetoric and culture by Neyrey, Jerome H., 1940- author. Book BS2825.52 .N495 2019 "Your God is a devouring fire": fire as a motif of divine presence and agency in the Hebrew Bible by Simone, Michael R., 1972- author. Book BS680.F53 S56 2019 Trinitarian and cosmotheandric vision by Panikkar, Raimon, Book BT111.3 .P36 2019 The life of Jesus: a graphic novel by Alex, Ben, author. Book BT302 .M66 2017 Our Lady of Guadalupe: the graphic novel by Muglia, Natalie, Book BT660.G8 M84 2018 An ecological theology of liberation: salvation and political ecology by Castillo, Daniel Patrick, author. Book BT83.57 .C365 2019 The Satan: how God's executioner became the enemy by Stokes, Ryan E., Book BT982 .S76 2019 Lectio Divina of the Gospels: for the liturgical year 2019-2020. -

Contemporary Interpretations of Christian Freedom and Christian Democracy in Hungary

Volume 49 Number 1 Article 5 September 2020 Contemporary Interpretations of Christian Freedom and Christian Democracy in Hungary Zsolt Szabo Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/pro_rege Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Szabo, Zsolt (2020) "Contemporary Interpretations of Christian Freedom and Christian Democracy in Hungary," Pro Rege: Vol. 49: No. 1, 14 - 21. Available at: https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/pro_rege/vol49/iss1/5 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at Digital Collections @ Dordt. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pro Rege by an authorized administrator of Digital Collections @ Dordt. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Contemporary Interpretations of Christian Freedom and Christian Democracy in Hungary paper, I attempt to present this concept, as well as the Christian origins and approaches to the concept of legal-political freedom, and today’s interpretation of Christian democracy. My the- sis is that all Christian governance is necessarily democratic, but not all democratic governance is Christian. Christian freedom Freedom in the Bible appears mainly as freedom from sins, available by personal repen- tance. We can talk about Jesus in this regard as a “liberator,” saving us from the captivity of by Zsolt SzabÓ our sins: “So if the Son sets you free, you will be free indeed” (John 8:36). From among the Introduction multiple Bible verses we quote here, those from It is well-known in Western Europe and the Romans (7:24-25) are the most significant: United States, but less so in Central Europe, “Who will rescue me from this body that is that Christianity, and Protestantism in particu- subject to death? Thanks be to God, who de- lar, had a great impact on the development of livers me through Jesus Christ our Lord!” The liberties and democracy in general. -

The Pre-History of Subsidiarity in Leo XIII

Journal of Catholic Legal Studies Volume 56 Number 1 Article 5 The Pre-History of Subsidiarity in Leo XIII Michael P. Moreland Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcls This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Catholic Legal Studies by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FINAL_MORELAND 8/14/2018 9:10 PM THE PRE-HISTORY OF SUBSIDIARITY IN LEO XIII MICHAEL P. MORELAND† Christian Legal Thought is a much-anticipated contribution from Patrick Brennan and William Brewbaker that brings the resources of the Christian intellectual tradition to bear on law and legal education. Among its many strengths, the book deftly combines Catholic and Protestant contributions and scholarly material with more widely accessible sources such as sermons and newspaper columns. But no project aiming at a crisp and manageably-sized presentation of Christianity’s contribution to law could hope to offer a comprehensive treatment of particular themes. And so, in this brief essay, I seek to elaborate upon the treatment of the principle of subsidiarity in Catholic social thought. Subsidiarity is mentioned a handful of times in Christian Legal Thought, most squarely with a lengthy quotation from Pius XI’s articulation of the principle in Quadragesimo Anno.1 In this proposed elaboration of subsidiarity, I wish to broaden the discussion of subsidiarity historically (back a few decades from Quadragesimo Anno to the pontificate of Leo XIII) and philosophically (most especially its relation to Leo XIII’s revival of Thomism).2 Statements of the principle have historically been terse and straightforward even if the application of subsidiarity to particular legal questions has not. -

ITALIAN MODERNITIES Competing Narratives of Nationhood

ITALIAN MODERNITIES Competing Narratives of Nationhood ITALIAN AND ITALIAN AMERICAN STUDIES AND ITALIAN ITALIAN Italian and Italian American Studies Series Editor Stanislao G. Pugliese Hofstra University Hempstead , New York, USA This series brings the latest scholarship in Italian and Italian American history, literature, cinema, and cultural studies to a large audience of spe- cialists, general readers, and students. Featuring works on modern Italy (Renaissance to the present) and Italian American culture and society by established scholars as well as new voices, it has been a longstanding force in shaping the evolving fi elds of Italian and Italian American Studies by re-emphasizing their connection to one another. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/14835 Rosario Forlenza • Bjørn Thomassen Italian Modernities Competing Narratives of Nationhood Rosario Forlenza Bjørn Thomassen Columbia University Roskilde University , Denmark New York , NY , USA University of Padua , Italy Italian and Italian American Studies ISBN 978-1-137-50155-4 ISBN 978-1-137-49212-8 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-49212-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016916082 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. -

Catholic Social Teaching and Sustainable Development: What the Church Provides for Specialists

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 8-19-2020 Catholic Social Teaching and Sustainable Development: What the Church Provides for Specialists Anthony Philip Stine Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Ethics in Religion Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Public Affairs Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Stine, Anthony Philip, "Catholic Social Teaching and Sustainable Development: What the Church Provides for Specialists" (2020). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 5604. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.7476 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Catholic Social Teaching and Sustainable Development: What the Church Provides for Specialists by Anthony Philip Stine A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public Affairs and Policy Dissertation Committee: Christopher Shortell, Chair Kent Robinson Jennifer Allen Daniel Jaffee Portland State University 2020 © 2020 Anthony Philip Stine Abstract The principles of Catholic Social Teaching as represented by the writings of 150 years of popes as well as the theorists inspired by those writings are examined, as well as the two principal schools of thought in the sustainability literature as represented by what is classically called the anthropocentric or managerial approach to sustainability as well as the biocentric school of thought. This study extends previous research by analyzing what the Catholic Church has said over the course of centuries on issues related to society, economics, and the environment, as embodied in the core concepts of subsidiarity, solidarity, stewardship, the common good, and integral human development. -

Facts for the Times

Valuable Historical Extracts. ,,,,,,, 40,11/1/, FACTS FOR THE TIMES. A COLLECTION —OF — VALUABLE HISTORICAL EXTRACTS ON A GR.E!T VA R TETY OF SUBJECTS, OF SPECIAL INTEREST TO THE BIBLE STUDENT, FROM EMINENT AUTHORS, ANCIENT AND MODERN. REVISED BY G. I. BUTLER. " Admissions in favor of troth, from the ranks of its enemies, constitute the highest kind of evidence."—Puss. Ass Mattatc. Pr This Volume contains about One Thousand Separate Historical Statements. THIRD EDITION, ENLARGED, AND BROUGHT DOWN TO 1885. REVIEW AND HERALD, BATTLE CREEK, MICH. PACIFIC PRESS, OAKLAND, CALIFORNIA. PREFACE. Tax object of this volume, as its name implies, is to furnish to the inquirer a large fund of facts bearing upon important Bible subjects, which are of special interest to the present generation, • While "the Bible and the Bible alone" is the only unerring rule of faith and practice, it is very desirable oftentimes to ascertain what great and good men have believed concerning its teachings. This is especially desirable when religious doctrines are being taught which were considered new and strange by some, but which, in reality, have bad the sanction of many of the most eminent and devoted of God's servants in the past. Within the last fifty years, great changes have occurred among religious teachers and churches. Many things which were once con- sidered important truths are now questioned or openly rejected ; while other doctrines which are thought to be strange and new are found to have the sanction of the wisest and best teachers of the past. The extracts contained in this work cover a wide range of subjects, many of them of deep interest to the general reader. -

Gen Assembly Report Extended V1

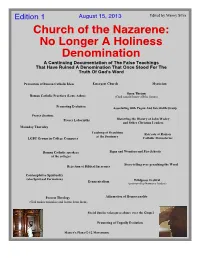

Edition 1 August 15, 2013 Edited by Manny Silva Church of the Nazarene: No Longer A Holiness Denomination A Continuing Documentation of The False Teachings That Have Ruined A Denomination That Once Stood For The Truth Of God's Word Promotion of Roman Catholic Ideas Emergent Church Mysticism Open Theism Roman Catholic Practices (Lent, Ashes) (God cannot know all the future) Promoting Evolution Associating with Pagan And Interfaith Group Prayer Stations Prayer Labyrinths Distorting the History of John Wesley and Other Christian Leaders Maunday Thursday Teaching of Occultism Retreats at Roman at the Seminary LGBT Groups in College Campuses Catholic Monasteries Roman Catholic speakers Signs and Wonders and Fire Schools at the colleges Story-telling over preaching the Word Rejection of Biblical Inerrancy Contemplative Spirituality (aka Spiritual Formation) Ecumenicalism Wildgoose Festival (promoted by Nazarene leaders) Process Theology Affirmation of Homosexuality (God makes mistakes and learns from them) Social Justice takes precedence over the Gospel Promoting of Ungodly Evolution Master's Plan (G-12 Movement) The Church of the Nazarene: General Assembly 2013 Report, And Various Papers Documenting The Heresies In The Church [This document can be copied and distributed to others to alert them to the state of the Church of the Nazarene and its universities and colleges. This document has been compiled for the sake of the brothers and sisters in Christ in the Church of the Nazarene. It is solely driven by love for those who may be, or have been, deceived by the many false teachings and teachers that have invaded the church. I cannot explain exactly why such blatantly unbiblical and satanic teachings have fooled so many. -

Autograph Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8pv6ps6 No online items Autograph Collection Mario A Gallardo, Clay Stalls William H. Hannon Library Loyola Marymount University One LMU Drive, MS 8200 Los Angeles, CA 90045-8200 Phone: (310) 338-5710 Fax: (310) 338-5895 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.lmu.edu/ © 2015 Loyola Marymount University. All rights reserved. Autograph Collection 007 1 Autograph Collection Collection number: 007 William H. Hannon Library Loyola Marymount University Los Angeles, California Processed by: Mario A Gallardo, Clay Stalls Date Completed: July 2015 Encoded by: Mario A Gallardo, Clay Stalls © 2015 Loyola Marymount University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Autograph collection Dates: 1578-1959 Collection number: 007 Collector: Charlotte E. Field Collection Size: 4 autograph albums Repository: Loyola Marymount University. Library. Department of Archives and Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90045-2659 Abstract: This collection consists of autographs of ecclesiastical figures, presidents, entertainers, and other personages, from the late sixteenth century to the mid twentieth century. Languages: Languages represented in the collection: English Access Collection is open to research under the terms of use of the Department of Archives and Special Collections, Loyola Marymount University. Publication Rights Materials in the Department of Archives and Special Collections may be subject to copyright. Unless explicitly stated otherwise, Loyola Marymount University does not claim ownership of the copyright of any materials in its collections. The user or publisher must secure permission to publish from the copyright owner. Loyola Marymount University does not assume any responsibility for infringement of copyright or of publication rights held by the original author or artists or his/her heirs, assigns, or executors. -

Democracy and Catholic Social Teaching: Continuity, Development, and Challenge

Studia Gilsoniana 3 (2014): 167–190 | ISSN 2300–0066 V. Bradley Lewis The Catholic University of America Washington D.C., USA DEMOCRACY AND CATHOLIC SOCIAL TEACHING: CONTINUITY, DEVELOPMENT, AND CHALLENGE My topic is the relationship between two phenomena that have been of long-standing interest to Jude Dougherty as scholar and public intellec- tual.1 They came together rather dramatically during the main years of his career, the time he served as dean of the School of Philosophy at the Catholic University of America. The University’s birth certificate, as it were, was the 1889 encyclical Magni nobis, promulgated by Leo XIII ten years after Aeterni patris, which initiated the Thomistic revival, and two years before Rerum novarum began the modern tradition of Catholic Social Teaching. The founding of the university and, in 1895 its School of Phi- losophy, was of a piece with Leo’s initiation of a confident address to the modern world in the wake of the political and social turbulence unleashed by the French Revolution. Leo’s project was one of vigorous intellectual engagement in which philosophy had an important role to play. No subse- quent pontiff embodied this more than St. John Paul II, who had visited Catholic University at Dean Dougherty’s invitation as the cardinal- archbishop of Krakow and then again as pope, a pope identified not only with the principles of the Gospel, but as a champion of both reason and political freedom. His papacy represented the culmination of a process by which the Church’s social teaching assessed with increasing nuance the character of democratic politics, moving from a diffidence rooted in the 1 See especially the essays collected in Western Creed, Western Identity: Essays in Legal and Social Philosophy (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 2000); and “The Fragility of Democracy,” in Die fragile Demokratie—The Fragility of Democracy, ed. -

Recovering Faithful Citizenship in a Postmodern Age

Mississippi College Law Review Volume 29 Issue 1 Vol. 29 Iss. 1 Article 5 2010 Putting the World Back Together - Recovering Faithful Citizenship in a Postmodern Age Harry G. Hutchison Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.law.mc.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Custom Citation 29 Miss. C. L. Rev. 149 (2010) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by MC Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mississippi College Law Review by an authorized editor of MC Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PUTTING THE WORLD BACK TOGETHER? RECOVERING FAITHFUL CITIZENSHIP IN A POSTMODERN AGE © Harry G. Hutchison' REVIEw ESSAY: RENDER UNTO CAESAR: SERVING THE NATION BY LIVING OUR CATHOLIC BELIEFS IN POLITICAL LIFE By CHARLES J. CHAPUT, O.F.M. CAP. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION............................................... 149 II. ARCHBISHOP CHAPUT's ARGUMENT ......................... 157 111. CONFLICT AND RECOVERY: RECLAIMING THE NATION'S IDENTITY IN THE MIRROR OF MODERN LIBERALISM ........ 164 A. Modern Liberalism as the Basis of Conflict ............. 164 B. The Contest for the Catholic Soul .................... 167 1. Finding Bases of Conflict ....................... 168 2. An Inevitable Conflict Reinforced by Indifference? . 170 C. Resolving the Role of Religion in the Public Square...... 175 D. The Catholic Roots of American Liberalism? ........... 180 IV. CONCLUSION ................................................. 188 I. INTRODUCTION Archbishop Chaput's book, Render Unto Caesar,signifies the continu- ation of an impressive and persistent debate about what it means to be Catholic and how Catholics should live out the teachings of the Church in political life in our pluralistic society.2 This query, much like H.L.A. -

The Catholic Bishops and the Rise of Evangelical Catholics

religions Article The Catholic Bishops and the Rise of Evangelical Catholics Patricia Miller Received: 27 October 2015; Accepted: 22 December 2015; Published: 6 January 2016 Academic Editor: Timothy A. Byrnes Senior Correspondent, Religion Dispatches; [email protected]; Tel.: +1-703-519-8379 Abstract: White Catholics are increasingly trending toward the Republican Party, both as voters and candidates. Many of these Republican-leaning Catholics are displaying a more outspoken, culture-war oriented form of Catholicism that has been dubbed Evangelical Catholicism. Through their forceful disciplining of pro-choice Catholics and treatment of abortion in their quadrennial voting guides, as well as their emphasis on “religious liberty”, the U.S. bishops have played a major role in the rise of these Evangelical Catholics. Keywords: U.S. Catholic bishops; abortion; Republican; Democratic; voting 1. Introduction While the Catholic Church is associated with opposition to legalized abortion, a review of the historical record shows that the anti-abortion movement was largely fomented by the Catholic hierarchy and fueled by grassroots Evangelical opposition to abortion [1]. Lay Catholics have largely tracked general public opinion on abortion, with just over half of white Catholics saying it should be legal; polls have consistently found that only about 13% of Catholics support the position of the Catholic Church that abortion should be illegal in all circumstances [2,3]. As a result, Catholic voters have been comfortable supporting candidates who favor abortion rights, adding to their reputation as swing voters who have backed both successful Republican and Democratic presidential candidates. However, a substantial subset of white Catholic voters now appears more firmly committed to the Republican Party.