Rerum Novarum and Natural Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One Hundred Years of Thomism Aeterni Patris and Afterwards a Symposium

One Hundred Years of Thomism Aeterni Patris and Afterwards A Symposium Edited By Victor B. Brezik, C.S.B, CENTER FOR THOMISTIC STUDIES University of St. Thomas Houston, Texas 77006 ~ NIHIL OBSTAT: ReverendJamesK. Contents Farge, C.S.B. Censor Deputatus INTRODUCTION . 1 IMPRIMATUR: LOOKING AT THE PAST . 5 Most Reverend John L. Morkovsky, S.T.D. A Remembrance Of Pope Leo XIII: The Encyclical Aeterni Patris, Leonard E. Boyle,O.P. 7 Bishop of Galveston-Houston Commentary, James A. Weisheipl, O.P. ..23 January 6, 1981 The Legacy Of Etienne Gilson, Armand A. Maurer,C.S.B . .28 The Legacy Of Jacques Maritain, Christian Philosopher, First Printing: April 1981 Donald A. Gallagher. .45 LOOKING AT THE PRESENT. .61 Copyright©1981 by The Center For Thomistic Studies Reflections On Christian Philosophy, All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or Ralph McInerny . .63 reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written Thomism And Today's Crisis In Moral Values, Michael permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in Bertram Crowe . .74 critical articles and reviews. For information, write to The Transcendental Thomism, A Critical Assessment, Center For Thomistic Studies, 3812 Montrose Boulevard, Robert J. Henle, S.J. 90 Houston, Texas 77006. LOOKING AT THE FUTURE. .117 Library of Congress catalog card number: 80-70377 Can St. Thomas Speak To The Modem World?, Leo Sweeney, S.J. .119 The Future Of Thomistic Metaphysics, ISBN 0-9605456-0-3 Joseph Owens, C.Ss.R. .142 EPILOGUE. .163 The New Center And The Intellectualism Of St. Thomas, Printed in the United States of America Vernon J. -

New Books for December 2019 Grace, Predestination, and the Permission of Sin: a Thomistic Analysis by O'neill, Taylor Patrick, A

New Books for December 2019 Grace, predestination, and the permission of sin: a Thomistic analysis by O'Neill, Taylor Patrick, author. Book B765.T54 O56 2019 Faith and the founders of the American republic Book BL2525 .F325 2014 Moral combat: how sex divided American Christians and fractured American politics by Griffith, R. Marie 1967- author. (Ruth Marie), Book BR516 .G75 2017 Southern religion and Christian diversity in the twentieth century by Flynt, Wayne, 1940- author. Book BR535 .F59 2016 The story of Latino Protestants in the United States by Martínez, Juan Francisco, 1957- author. Book BR563.H57 M362 2018 The land of Israel in the Book of Ezekiel by Pikor, Wojciech, Book BS1199.L28 P55 2018 2 Kings by Park, Song-Mi Suzie, author. Book BS1335.53 .P37 2019 The Parables in Q by Roth, Dieter T., author. Book BS2555.52 .R68 2018 Hearing Revelation 1-3: listening with Greek rhetoric and culture by Neyrey, Jerome H., 1940- author. Book BS2825.52 .N495 2019 "Your God is a devouring fire": fire as a motif of divine presence and agency in the Hebrew Bible by Simone, Michael R., 1972- author. Book BS680.F53 S56 2019 Trinitarian and cosmotheandric vision by Panikkar, Raimon, Book BT111.3 .P36 2019 The life of Jesus: a graphic novel by Alex, Ben, author. Book BT302 .M66 2017 Our Lady of Guadalupe: the graphic novel by Muglia, Natalie, Book BT660.G8 M84 2018 An ecological theology of liberation: salvation and political ecology by Castillo, Daniel Patrick, author. Book BT83.57 .C365 2019 The Satan: how God's executioner became the enemy by Stokes, Ryan E., Book BT982 .S76 2019 Lectio Divina of the Gospels: for the liturgical year 2019-2020. -

The Pre-History of Subsidiarity in Leo XIII

Journal of Catholic Legal Studies Volume 56 Number 1 Article 5 The Pre-History of Subsidiarity in Leo XIII Michael P. Moreland Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcls This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Catholic Legal Studies by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FINAL_MORELAND 8/14/2018 9:10 PM THE PRE-HISTORY OF SUBSIDIARITY IN LEO XIII MICHAEL P. MORELAND† Christian Legal Thought is a much-anticipated contribution from Patrick Brennan and William Brewbaker that brings the resources of the Christian intellectual tradition to bear on law and legal education. Among its many strengths, the book deftly combines Catholic and Protestant contributions and scholarly material with more widely accessible sources such as sermons and newspaper columns. But no project aiming at a crisp and manageably-sized presentation of Christianity’s contribution to law could hope to offer a comprehensive treatment of particular themes. And so, in this brief essay, I seek to elaborate upon the treatment of the principle of subsidiarity in Catholic social thought. Subsidiarity is mentioned a handful of times in Christian Legal Thought, most squarely with a lengthy quotation from Pius XI’s articulation of the principle in Quadragesimo Anno.1 In this proposed elaboration of subsidiarity, I wish to broaden the discussion of subsidiarity historically (back a few decades from Quadragesimo Anno to the pontificate of Leo XIII) and philosophically (most especially its relation to Leo XIII’s revival of Thomism).2 Statements of the principle have historically been terse and straightforward even if the application of subsidiarity to particular legal questions has not. -

Gen Assembly Report Extended V1

Edition 1 August 15, 2013 Edited by Manny Silva Church of the Nazarene: No Longer A Holiness Denomination A Continuing Documentation of The False Teachings That Have Ruined A Denomination That Once Stood For The Truth Of God's Word Promotion of Roman Catholic Ideas Emergent Church Mysticism Open Theism Roman Catholic Practices (Lent, Ashes) (God cannot know all the future) Promoting Evolution Associating with Pagan And Interfaith Group Prayer Stations Prayer Labyrinths Distorting the History of John Wesley and Other Christian Leaders Maunday Thursday Teaching of Occultism Retreats at Roman at the Seminary LGBT Groups in College Campuses Catholic Monasteries Roman Catholic speakers Signs and Wonders and Fire Schools at the colleges Story-telling over preaching the Word Rejection of Biblical Inerrancy Contemplative Spirituality (aka Spiritual Formation) Ecumenicalism Wildgoose Festival (promoted by Nazarene leaders) Process Theology Affirmation of Homosexuality (God makes mistakes and learns from them) Social Justice takes precedence over the Gospel Promoting of Ungodly Evolution Master's Plan (G-12 Movement) The Church of the Nazarene: General Assembly 2013 Report, And Various Papers Documenting The Heresies In The Church [This document can be copied and distributed to others to alert them to the state of the Church of the Nazarene and its universities and colleges. This document has been compiled for the sake of the brothers and sisters in Christ in the Church of the Nazarene. It is solely driven by love for those who may be, or have been, deceived by the many false teachings and teachers that have invaded the church. I cannot explain exactly why such blatantly unbiblical and satanic teachings have fooled so many. -

Solidarity and Mediation in the French Stream Of

SOLIDARITY AND MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Timothy R. Gabrielli Dayton, Ohio December 2014 SOLIDARITY AND MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Name: Gabrielli, Timothy R. APPROVED BY: _________________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor _________________________________________ Dennis M. Doyle, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Anthony J. Godzieba, Ph.D. Outside Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Vincent J. Miller, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Daniel S. Thompson, Ph.D. Chairperson ii © Copyright by Timothy R. Gabrielli All rights reserved 2014 iii ABSTRACT SOLIDARITY MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Name: Gabrielli, Timothy R. University of Dayton Advisor: William L. Portier, Ph.D. In its analysis of mystical body of Christ theology in the twentieth century, this dissertation identifies three major streams of mystical body theology operative in the early part of the century: the Roman, the German-Romantic, and the French-Social- Liturgical. Delineating these three streams of mystical body theology sheds light on the diversity of scholarly positions concerning the heritage of mystical body theology, on its mid twentieth-century recession, as well as on Pope Pius XII’s 1943 encyclical, Mystici Corporis Christi, which enshrined “mystical body of Christ” in Catholic magisterial teaching. Further, it links the work of Virgil Michel and Louis-Marie Chauvet, two scholars remote from each other on several fronts, in the long, winding French stream. -

Introduction

Introduction I was working in my office on a warm spring day in 2014 when I received a phone call from a friend who was working in Guatemala. There was urgency in her voice as she told me that a young woman named Ana was in trouble with gangs in Guatemala City.1 Ana’s family feared for her life. They had good reason to be fearful: they had firsthand experience with gang violence. They were reaching out to me, asking if we could take Ana to live with us because we, too, are part of their family. I have two daughters whom I adopted from Guatemala. In 2013, after a highly complicated investigation, our birth family searcher was able to locate the girls’ families. As we got to know them and visited them, we learned more about the reasons they had relinquished their children for adoption. Our younger daughter, Malaya, comes from a family that is extremely indigent. At the time they conceived Malaya, they were living in a squatter settlement of shanty homes, patched together from sheets of corrugated tin. They constantly feared eviction, and they often did not have enough to feed their children. Malaya’s birth father told me that he worried that Malaya might starve to death. Her parents wanted her to have a life where she did not lack the basic necessities and could get an education that they are not able to provide. Our older daughter, Linnea, was born in Guatemala City to a family of greater economic means. Yet, due to Guatemala’s unstable economy, the family still finds it difficult to make ends meet, despite the fact that her older siblings had advanced education and professional positions. -

Father Raymond S. Clancy Papers

FATHER RAYMOND S. CLANCY (1904-1971) COLLECTION Papers, 1896-1970 (Predominantly, 1938-1954) 5 1/2 linear feet Accession Number 499 L.C. Number The papers of the Reverend Father Raymond Scullin Clancy were placed in the Archives of Labor History and Urban Affairs in October, 1971, by Father John O'Connor and were opened for research in February, 1973. Known as Detroit's "Labor Priest," Fr. Clancy was born (June 15, 1904) and educated in Detroit, graduating from the University of Detroit in 1924. After attending St. Gregory's Preparatory Seminary, Mt. Washington, Ohio, and Mt. St. Mary's Seminary of the West, Norwood, Ohio, he was ordained into the Roman Catholic priesthood May 26, 1929. For the following eleven years he served as assistant pastor and then administrator of Church of the Epiphany in Detroit. In 1938, after special training in Roman Catholic social principles, Fr. Clancy was named executive secretary of the Catholic Conference on Indus- trial Problems which met in Detroit in January, 1939. Also named executive secretary of the (Detroit) Archdiocesan Labor Institute, he launched a pro- gram of labor education for Roman Catholic workers in 1939/40. Beginning with eight experimental parish schools, the Institute, which worked in coopera- tion with the Detroit Association of Catholic Trade Unionists, grew to forty schools, the largest such program in any Roman Catholic diocese in the world. In addition, Fr. Clancy became Director of the Social Action Department of the Detroit Archdiocese, a position he held into the 1950's. During this period he was a frequent spokesman for the adoption of Roman Catholic social and economic principles, especially as enunciated in the papal encyclicals, Rerum Novarum and Quadragesimo Anno, as well as post-World War II planning. -

Quadragesimo Anno (The Fortieth Year ) on Reconstruction of the Social Order

Quadragesimo Anno (The Fortieth Year ) On Reconstruction of the Social Order Pius XI, 1931 Encyclical of Pope Pius Xl issued on May 15, 1931 To Our Venerable Brethren, the Patriarchs, Primates, Archbishops, Bishops and other Ordinaries in Peace and Communion with the Holy See, and Likewise to All the Faithful of the Catholic World. Venerable Brethren and Beloved Children, Health and Apostolic Benediction. 1. Forty years have passed since Leo Xlll's peerless Encyclical, On the Condition of Workers, first saw the light, and the whole Catholic world, filled with grateful recollection, is undertaking to commemorate it with befitting solemnity. 2. Other Encyclicals of Our Predecessor had in a way prepared the path for that outstanding document and proof of pastoral care: namely, those on the family and the Holy Sacrament of Matrimony as the source of human society,[1] on the origin of civil authority[2] and its proper relations with the Church,[3] on the chief duties of Christian citizens,[4] against the tenets of Socialism[5] against false teachings on human liberty,[6] and others of the same nature fully expressing the mind of Leo Xlll. Yet the Encyclical, On the Condition of Workers, compared with the rest had this special distinction that at a time when it was most opportune and actually necessary to do so, it laid down for all mankind the surest rules to solve aright that difficult problem of human relations called "the social question." 3. For toward the close of the nineteenth century, the new kind of economic life that had arisen and the new developments of industry had gone to the point in most countries that human society was clearly becoming divided more and more into two classes. -

MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES to MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to the College of Arts and Sciences Of

MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES TO MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Matthew Glen Minix UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio December 2016 MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES TO MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Name: Minix, Matthew G. APPROVED BY: _____________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Dissertation Director _____________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Dissertation Reader. _____________________________________ Anthony Burke Smith, Ph.D. Dissertation Reader _____________________________________ John A. Inglis, Ph.D. Dissertation Reader _____________________________________ Jack J. Bauer, Ph.D. _____________________________________ Daniel Speed Thompson, Ph.D. Chair, Department of Religious Studies ii © Copyright by Matthew Glen Minix All rights reserved 2016 iii ABSTRACT MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES TO MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Name: Minix, Matthew Glen University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. Sandra A. Yocum This dissertation considers a spectrum of five distinct approaches that mid-twentieth century neo-Thomist Catholic thinkers utilized when engaging with the tradition of modern scientific psychology: a critical approach, a reformulation approach, a synthetic approach, a particular [Jungian] approach, and a personalist approach. This work argues that mid-twentieth century neo-Thomists were essentially united in their concerns about the metaphysical principles of many modern psychologists as well as in their worries that these same modern psychologists had a tendency to overlook the transcendent dimension of human existence. This work shows that the first four neo-Thomist thinkers failed to bring the traditions of neo-Thomism and modern psychology together to the extent that they suggested purely theoretical ways of reconciling them. -

Rerum Novarum: New Things and Recent Paradigms of Property Law

Florida International University College of Law eCollections Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 2016 Rerum Novarum: New Things and Recent Paradigms of Property Law M C. Mirow Florida International University College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecollections.law.fiu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the International Law Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation M C. Mirow, Rerum Novarum: New Things and Recent Paradigms of Property Law , 47 U. Pac. L. Rev. 183 (2016). Available at: https://ecollections.law.fiu.edu/faculty_publications/268 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at eCollections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCollections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rerum Novarum: New Things and Recent Paradigms of Property Law M.C. Mirow* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 183 II. SPRANKLING’S THE INTERNATIONAL LAW OF PROPERTY ............................. 184 III. LEO XIII’S RERUM NOVARUM ....................................................................... 188 IV. SOME CONCLUDING OBSERVATIONS ........................................................... 196 I. INTRODUCTION In science, when someone discovers a new beetle, detects a new particle, or isolates a new element, we get tweets, blog posts, and articles in the Sacramento Bee, -

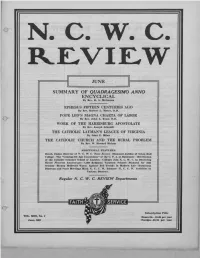

June Summary of Quadragesimo Anno

c. c. JUNE SUMMARY OF QUADRAGESIMO ANNO ENCYCLICAL By Rev. R. A. McGowan EPHESUS FIFTEEN CENTURIES AGO By Rev. Hubert L. Motry, D.D. POPE LEO'S MAGNA CHARTA OF LABOR By Rev. John A. Ryan, D.D. WORK OF THE HARRISBURG APOSTOLATE By Rev. Joseph Schmidt THE CATHOLIC LAYMAN'S LEAGUE OF VffiGINIA By John E. Milan THE CATHOLIC CHURCH AND THE RURAL PROBLEM By Rev. W. Howard Bishop ADDITIONAL FEATURES Death Claims Director of N. C. W. C. New. Service- Diamond Jubilee of Seton Hall College-The "Coming-Of-Age Convention" of the C. P. A. at Baltimore-1931 Session of the Catholic Summer School of America- Colleges Join N. C. W. C. in Observing Rerum Novarum Anniversary-l,OOO Religious Vacation Schools Planned for 1931 Session-Bishop McDevitt Warns Against Evil Trends in Modern Life-Numerous Diocesan and State Meetings Mark N. C. C. W. Advance-N. C. C. W. Activities in Variou s Dioceses. Regular N. C. W. C. REVIEW Department. Subscription Price VOL. XIU, No. 6 Domes tic-$1.00 per year June, 1931 Foreign-'1.Z5 per year 2 N. C. W. C. REVIEW June, 1931 N. C. W. C. REVIEW OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE NATIONAL CATHOLIC WELFARE CONFERENCE N. c. w. C. Administrative {{This organization (the N. C. Purpose of the N. C. W. C. Committee W. C.) is not only useful, but IN THE WORDS OF OUR HOLY FATHER: MOST REV. EDWARD .1. HANNA, D.D. necessary. .. We praise all "Since you (the Bishops) reside in Archbishop of San FranciscQ cities far apart and there are matters who in any way cooperate in this of a higher import demanding your Chairman great work."-POPE PIUS XI. -

Unlocking Catholic Social Doctrine: Narrative Is Key

The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law CUA Law Scholarship Repository Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions Faculty Scholarship 2010 Unlocking Catholic Social Doctrine: Narrative is Key William J. Wagner The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/scholar Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation William J. Wagner, Unlocking Catholic Social Doctrine: Narrative is Key, 7 J. CATH. SOCIAL THOUGHT 289 (2010). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions by an authorized administrator of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Unlocking Catholic Social Doctrine: Narrative as Key William Joseph Wagner I. Introduction In the case of the Catholic law school at least, Catholic social doctrine answers a need. The Catholic Church is in need of a program and Catholic law schools are there to advance that program, so for this reason there must be Catholic social doctrine. The stance of the Church, as reflected in the existence of these Catholic law schools, reflects a dual commitment of service to the good of the larger society, on essentially its terms, and, at the same time, to the integrity of the Church’s own perspective independent of the drift of society.1 The Church’s need for independence flows from the integrity of the faith.2 As a result of this dual requirement, the Church needs directives that travel light so that they can encapsulate and preserve the distinctive Catholic difference, but still be adopted within a law school structured to the needs of the William Wagner is Professor of Law and Director, Center for Law, Philosophy and Culture, Columbus School of Law, the Catholic University of America.