Conspiracy Law's Threat to Free Speech

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Timely History of Cheating and Fraud Following Ivey V Genting Casinos (UK)

The honest cheat: a timely history of cheating and fraud following Ivey v Genting Casinos (UK) Ltd t/a Crockfords [2017] UKSC 67 Cerian Griffiths Lecturer in Criminal Law and Criminal Justice, Lancaster University Law School1 Author email: [email protected] Abstract: The UK Supreme Court took the opportunity in Ivey v Genting Casinos (UK) Ltd t/a Crockfords [2017] UKSC 67 to reverse the long-standing, but unpopular, test for dishonesty in R v Ghosh. It reduced the relevance of subjectivity in the test of dishonesty, and brought the civil and the criminal law approaches to dishonesty into line by adopting the test as laid down in Royal Brunei Airlines Sdn Bhd v Tan. This article employs extensive legal historical research to demonstrate that the Supreme Court in Ivey was too quick to dismiss the significance of the historical roots of dishonesty. Through an innovative and comprehensive historical framework of fraud, this article demonstrates that dishonesty has long been a central pillar of the actus reus of deceptive offences. The recognition of such significance permits us to situate the role of dishonesty in contemporary criminal property offences. This historical analysis further demonstrates that the Justices erroneously overlooked centuries of jurisprudence in their haste to unite civil and criminal law tests for dishonesty. 1 I would like to thank Lindsay Farmer, Dave Campbell, and Dave Ellis for giving very helpful feedback on earlier drafts of this article. I would also like to thank Angus MacCulloch, Phil Lawton, and the Lancaster Law School Peer Review College for their guidance in developing this paper. -

Crimes Against Property

9 CRIMES AGAINST PROPERTY Is Alvarez guilty of false pretenses as a Learning Objectives result of his false claim of having received the Congressional Medal of 1. Know the elements of larceny. Honor? 2. Understand embezzlement and the difference between larceny and embezzlement. Xavier Alvarez won a seat on the Three Valley Water Dis- trict Board of Directors in 2007. On July 23, 2007, at 3. State the elements of false pretenses and the a joint meeting with a neighboring water district board, distinction between false pretenses and lar- newly seated Director Alvarez arose and introduced him- ceny by trick. self, stating “I’m a retired marine of 25 years. I retired 4. Explain the purpose of theft statutes. in the year 2001. Back in 1987, I was awarded the Con- gressional Medal of Honor. I got wounded many times by 5. List the elements of receiving stolen property the same guy. I’m still around.” Alvarez has never been and the purpose of making it a crime to receive awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, nor has he stolen property. spent a single day as a marine or in the service of any 6. Define forgery and uttering. other branch of the United States armed forces. The summer before his election to the water district board, 7. Know the elements of robbery and the differ- a woman informed the FBI about Alvarez’s propensity for ence between robbery and larceny. making false claims about his military past. Alvarez told her that he won the Medal of Honor for rescuing the Amer- 8. -

The Physical Element Or Actus Reus of Money Laundering 1. Overview In

CHAPTER FOUR THE PHYSICAL ELEMENT OR ACTUS REUS OF MONEY LAUNDERING 1. Overview In criminal law an intentional offence is usually analysed through a basic distinc- tion between the physical or objective element (the actus reus) and the mental or subjective element (the mens rea). The prosecution must prove both the specific objective facts and the accussed’s criminal intent or ‘guilty mind’. To the criminal lawyer, the ‘elements of the offence’ are fundamental because they set out the ground rules of the trial, showing what must be proven by the prosecution for a case to reach a conviction. In the event the prosecution establishes all the ele- ments of the offence beyond a reasonable doubt (or, in other words, beyond the intime conviction) of the trier of fact, then a conviction may lie. Nevertheless, if the defense casts a reasonable doubt on even one element of the offence, then the accused is entitled to acquittal. Later, in chapter V, we will address the subjective or mental element of the criminal offence called ‘money laundering’ or ‘laundering the proceeds of crime’. This chapter will try to determine whether or not the implementation of basic physical or actus reus elements of this international criminal offence at the domestic level might undermine the guarantee of due process and the adequate protection of human rights principles, such as the legality principle and the pre- sumption of innocence. And, if the adaptation of any physical element of the international crime proves to be inconsistent with human rights principles I will propose how the deficiencies can be remedied. -

Criminal Law Robbery & Burglary

Criminal Law Robbery & Burglary Begin by identifying the defendant and the behaviour in question. Then consider which offence applies: Robbery – Life imprisonment (S8(2) Theft Act 1968) Burglary – 14 years imprisonment (S9(1)(a) or S9(1)(b) Theft Act 1968) Robbery (S8(1) Theft Act 1968) Actus Reus: •! Stole (Satisfies the AR of Theft) •! Used or threatened force on any person →! R v Dawson – ‘Force’ is a word in ordinary use and it is a matter for the jury in each case to determine whether force had been used (or threatened) – but it need not be significant →! R v Clouden – Force may be applied to someone’s property →! S8(1) Theft Act 1968 – May be in relation to any person, but in regards to 3rd parties, they must be aware of the threat •! Force or threat of force was immediately before or at the time of the theft; and →! R v Hale – If appropriation was continuing and force was used at the time of the theft, the defendants could be guilty of robbery (jury’s decision) •! Force or threat of force was used in order to steal →! R v Vinall – Convictions for robbery were quashed because defendants were not proven to have had an intention to permanently deprive the victim of his property at the point when force was used on the victim Criminal Law Mens Rea: •! MR for Theft i.e. dishonesty and intention to permanently deprive •! Intention as to the use or threat of force Burglary Criminals who are ‘armed’ when they commit an offence of burglary can also face liability for an aggravated offence of burglary under S10 Theft Act 1968. -

The Elements of a Crime: a Brief Study on Actus Reus and Mens Rea

Revista Internacional d’Humanitats 49 mai-ago 2020 CEMOrOc-Feusp / Univ. Autònoma de Barcelona The Elements of a Crime: a Brief Study on Actus Reus and Mens Rea Enric Mallorquí-Ruscalleda1 Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis Resumen: En este artículo, y con el objetivo de entender mejor los elementos fundamentales sobre los que se articula el derecho penal de los Estados Unidos de América, me propongo: 1) definir el actus reus y la mens rea; 2) trazar su genealogía histórica y su transformación, especialmente por lo que a la mens rea se refiere; 3) lo anterior se completa con un breve comentario de los principales casos legales que han ido conformando la mens rea tal y como se conoce actualmente. Palabras Clave: derecho penal; actus reus; mens rea; case law; common law; Model Penal Code. Abstract: In this essay, and with the purpose of better understanding the fundamental elements on which the U.S. criminal law is based, I propose, mainly: 1) to define actus reus and mens rea; 2) to trace their genealogy and historical evolution, especially as far as men rea is concerned; 3) the above will be completed with a brief comment on legal cases that were once very important in relation to mens rea. Keywords: Criminal law; actus reus; mens rea; case law; common law; Model Penal Code. 1. Introduction The two essential elements of any crime, in addition to the necessary concurrence between them, as will be discussed below, are the so-called actus reus and mens rea. In this regard, a notable scholar like Eugene J. -

1 June 2015 TRIAL CHAMBER VII Before

ICC-01/05-01/13-978 02-06-2015 1/19 EC T Original: English No.: ICC-01/05-01/13 Date: 1 June 2015 TRIAL CHAMBER VII Before: Judge Chile Eboe-Osuji, Presiding Judge Judge Olga Herrera Carbuccia Judge Bertram Schmitt SITUATION IN THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC IN THE CASE OF THE PROSECUTOR v. JEAN-PIERRE BEMBA GOMBO, AIMÉ KILOLO MUSAMBA, JEAN-JACQUES MANGENDA KABONGO, FIDÈLE BABALA WANDU AND NARCISSE ARIDO Public with Public Annexes A and B Narcisse Arido’s Submissions on the Elements of Article 70 Offences and the Applicable Modes of Liability (ICC-01/05-01/13-T-8-CONF-ENG) Source: Counsel for Narcisse Arido ICC-01/05-01/13 1/19 1 June 2015 ICC-01/05-01/13-978 02-06-2015 2/19 EC T Document to be notified in accordance with regulation 31 of the Regulations of the Court to: The Office of the Prosecutor Counsel for Jean-Pierre Bemba Gombo Fatou Bensouda Melinda Taylor James Stewart Kweku Vanderpuye Counsel for Aimé Kilolo Musamba Paul Djunga Mudimbi Counsel for Jean-Jacques Mangenda Kabongo Christopher Gosnell Counsel for Fidèle Babala Wandu Jean-Pierre Kilenda Kakengi Basila Counsels for Narcisse Arido Charles Achaleke Taku Philippe Larochelle Legal Representatives of the Victims Legal Representatives of the Applicants Unrepresented Victims Unrepresented Applicants (Participation/Reparation) The Office of Public Counsel for The Office of Public Counsel for the Defence Victims Xavier-Jean Keïta REGISTRY Counsel Support Section Registrar Herman von Hebel Victims and Witnesses Unit Detention Section Nigel Verrill ICC-01/05-01/13 2/19 1 June 2015 ICC-01/05-01/13-978 02-06-2015 3/19 EC T I. -

CH 11 Conspiracy and Solicitation

CONSPIRACY & SOLICITATION .............................................................. 1 §11-1 Conspiracy ................................................................................................... 1 §11-2 Solicitation .................................................................................................. 4 i CONSPIRACY & SOLICITATION §11-1 Conspiracy United States Supreme Court Smith v. U.S., 568 U.S. 106, 133 S.Ct. 714, 184 L. Ed.2d 570 (2013) Although the prosecution has the burden to prove beyond a reasonable doubt every fact necessary to constitute the crime with which the defendant is charged, the constitution does not require that the prosecution disprove all affirmative defenses raised by the defense. Instead, the burden of proof may be assigned to the defendant if the affirmative defense in question does not negate an element of the crime. Although the legislative branch may choose to assign the burden of proof concerning other affirmative defenses to the prosecution, the constitution does not require it to do so. Where a defendant was charged with conspiracy and claimed that he had withdrawn from the conspiracy at such time that the statute of limitations expired before the prosecution was brought, the constitution did not require that the prosecution bear the burden of disproving the affirmative defense of withdrawal. A withdrawal defense does not negate an element of conspiracy, but merely determines the point at which the defendant is no longer criminally responsible for acts which his co-conspirators took in furtherance of the conspiracy. Because the defense did not negate any elements of conspiracy, the constitution was not violated because Congress followed the common law rule by assigning to the defendant the burden to prove he had withdrawn from the conspiracy. The court also noted the “informational asymmetry” between the defense and the prosecution concerning the defense of withdrawal. -

Mens Rea and Inchoate Crimes Larry Alexander

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 87 Article 2 Issue 4 Summer Summer 1997 Mens Rea and Inchoate Crimes Larry Alexander Kimberly D. Kessler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Larry Alexander, Kimberly D. Kessler, Mens Rea and Inchoate Crimes, 87 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 1138 (1996-1997) This Criminal Law is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/97/8704-1138 THE JouRmAL OF CRIMINAL LAw & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 87, No. 4 Copyright © 1997 by Northwestern University, School of Law Printed in U.S.A. MENS REA AND INCHOATE CRIMES LARRY ALEX&ND* KIMBERLY D. KESSLER** I. INTRODUCTION When a defendant engages in proscribed conduct or in conduct that brings about a forbidden result, our interest focuses on his state of mind at the time he engages in the proscribed conduct or the con- duct that causes the result. We usually are unconcerned with his state(s) of mind in the period leading up to the conduct. The narra- tive of the crime can begin as late as the moment defendant engages in the conduct (or, in the case of completed attempts,1 believes he is engaging in the conduct). Criminal codes do not restrict themselves to proscribing harmful conduct or results, however, but also criminalize various acts that pre- cede harmful conduct. -

Criminal Law Outline Rachel Barkow Spring 2014

CRIMINAL LAW OUTLINE RACHEL BARKOW SPRING 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction A. The Criminal Justice System in the US B. The Role of the Prosecutor C. The Role of the Jury D. What to Punish? E. The Justification of Punishment II. Building Blocks of Criminal Law A. Legality B. Culpability and Elements of the Offense 1. Actus Reus/Omissions 2. Mens Rea a) Basic Conceptions and Applications b) Mistake of Fact c) Strict Liability d) Mistake of Law and the Cultural Defense III. Substantive Offenses A. Homicide and the Grading of Offenses 1. Premeditation/Deliberation 2. Provocation 3. Unintentional Killing 4. Felony Murder 5. Causation B. Rape 1. Introduction 2. Actus Reus 3. Mens Rea C. Blackmail IV. Attempts A. Mens Rea B. Actus Reus/Preparation V. Group Criminality A. Accountability for the Acts of Others 1. Mens Rea 2. Natural and Probable Consequences Theory 3. Actus Reus B. Conspiracy 1. Actus Reus and Mens Rea 2. Conspiracy as Accessory Liability 3. Duration and Scope of a Conspiracy 4. Reassessing the Law of Conspiracy 1 C. Corporate Criminal Liability VI. General Defenses to Liability A. Overview B. Justifications 1. Self Defense 2. Defense of Property 3. Necessity C. Excuses 1. Insanity 2. Expansion of Excuses 3. Duress VII. The Imposition of Criminal Punishment A. Sentencing B. Proportionality 2 INTRODUCTION Criminal Justice System in the U.S. I. Mass Incarceration and its Causes and Consequences A. Mass incarceration • Massive in terms of total numbers • Massive in terms of disproportionate impact on people of color B. Causes -

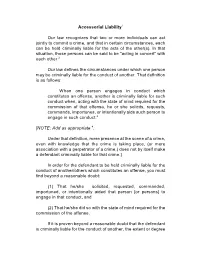

Accessorial Liability1 Our Law Recognizes That Two Or More

Accessorial Liability1 Our law recognizes that two or more individuals can act jointly to commit a crime, and that in certain circumstances, each can be held criminally liable for the acts of the other(s). In that situation, those persons can be said to be "acting in concert" with each other.2 Our law defines the circumstances under which one person may be criminally liable for the conduct of another. That definition is as follows: When one person engages in conduct which constitutes an offense, another is criminally liable for such conduct when, acting with the state of mind required for the commission of that offense, he or she solicits, requests, commands, importunes, or intentionally aids such person to engage in such conduct.3 [NOTE: Add as appropriate 4: Under that definition, mere presence at the scene of a crime, even with knowledge that the crime is taking place, (or mere association with a perpetrator of a crime,) does not by itself make a defendant criminally liable for that crime.] In order for the defendant to be held criminally liable for the conduct of another/others which constitutes an offense, you must find beyond a reasonable doubt: (1) That he/she solicited, requested, commanded, importuned, or intentionally aided that person [or persons] to engage in that conduct, and (2) That he/she did so with the state of mind required for the commission of the offense. If it is proven beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant is criminally liable for the conduct of another, the extent or degree of the defendant's participation in the crime does not matter. -

G153 Criminal Law: Offences Against Property

G153 Criminal Law: Offences Against Property ROBBERY By the end of this unit, you should be able to: Explain the actus reus and mens rea of robbery Evaluate the current law on robbery. Robbery is an indictable offence, which means that it is tried in the . It carries a maximum of a life sentence, and remember that a second conviction of robbery may lead to an automatic life sentence if serious under the Crime (Sentences) Act 1997. So, what is robbery? Simply put.... Theft + Violence = Robbery All elements immediately before s.8 Theft Act 1968 in s.2-8 of the or at the time of Theft Act 1968 the theft So... you have to have a complete theft. As revision, find and list all elements of theft below: B D M Y T R E P O R P A P 1. I S R T P S I V N O E K E R T V E V T U J T O Q G R 2. X Z Q O H D N S P F V N M 3. I N T E N T I O N D P I A Y L T S E N O H S I D G N 4. A P T I I J R N C P T N E 5. A P P R O P R I A T I O N Y J Y Q O P C Y U R V L T G Q D S A O B W U Q Y E L G X R V X H U X Q L G B Y D E P R I V E B B X G Z K S O G G G R W A M S W V A 1 G153 Criminal Law: Offences Against Property ACTUS REUS The actus reus is that for theft, plus force or the threat of force on any person immediately before or at the time of stealing. -

Application of the Vicarious Liability Principles in Environmental Crime

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 358 3rd International Conference on Globalization of Law and Local Wisdom (ICGLOW 2019) Application of the Vicarious Liability Principles in Environmental Crime Kuat Puji Prayitno1; Dwi Hapsari Retnaningrum2 1,2 Universitas Jenderal Soedirman, Purwokerto – Indonesia [email protected] Abstract- Environmental crime is one of the criminal acts of humans and other living beings [2]. In 2016 has been a that may lead to significant negative impact and/or damage colorful year in policy and enforcement of environmental to human sustainability. Therefore, in criminal law, criminal law in Indonesia. Opened with a negative note on the acts related to the environment needs to be specifically decision of the Palembang District Court in favor of PT regulated. The regulation can exist outside or comes in Bumi Mekar Hijau (PT BMH) against the Ministry of different form from the Criminal Code. The application of the vicarious liability principle include but not limited to the Environment and Forestry (KLHK) in a case of forest subject of criminal acts and criminal liability. The study aim fires (Karhutla) [3]. Forest fires are one of the crimes that to analyze the primary reason for the application of the are regulated in UUPPLH. The criminal act in the vicarious liability, whether the application of the vicarious Criminal Code Bill is interpreted as an act of doing or not liability is appropriate and the formulation of sanctions for doing something which is stated as a prohibited act and perpetrators in environmental crime . The method used is threatened by criminal law.