Economies of Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Petroleum Politics: China and Its National Oil Companies

MASTER IN ADVANCED EUROPEAN AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES ANGLOPHONE BRANCH - Academic year 2012/2013 Master Thesis Petroleum Politics: China and Its National Oil Companies By Ellennor Grace M. FRANCISCO 26 June 2013 Supervised by: Dr. Laurent BAECHLER Deputy Director MAEIS To Whom I owe my willing and my running CONTENTS List of Tables and Figures v List of Abbreviations vi Chapter 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Literature Review 2 1.2 Methodologies 4 1.3 Objectives and Scope 4 Chapter 2. Historical Evolution of Chinese National Oil Companies 6 2.1 The Central Government and “Self-Reliance” (1950- 1977) 6 2.2 Breakdown and Corporatization: First Reform (1978- 1991) 7 2.3 Decentralization: Second Reform (1992- 2003) 11 2.4 Government Institutions and NOCs: A Move to Recentralization? (2003- 2010) 13 2.5 Corporate Governance, Ownership and Marketization 15 2.5.1 International Market 16 2.5.2 Domestic Market 17 Chapter 3. Chinese Politics and NOC Governance 19 3.1 CCP’s Controlling Mechanisms 19 3.1.1 State Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) 19 3.1.2 Central Organization Department 21 3.2 Transference Between Government and Corporate Positions 23 3.3 Traditional Connections and the Guanxi 26 3.4 Convergence of NOC Politics 29 Chapter 4. The “Big Four”: Overview of the Chinese Banking Sector 30 Preferential Treatment 33 Chapter 5. Oil Security and The Going Out Policy 36 5.1 The Policy Driver: Equity Oil 36 5.2 The Going Out Policy (zou chu qu) 37 5.2.1 The Development of OFDI and NOCs 37 5.2.2 Trends of Outward Foreign Investments 39 5.3 State Financing: The Chinese Policy Banks 42 5.4 Loans for Oil 44 Chapter 6. -

The Politics of Oil, Gas Contract Negotiations in Sub-Saharan Africa

The politics of oil, gas contract negotiations in Sub-Saharan Africa This article is part of DIIS Report 2014:25 “Policies and finance for economic development and trade” Read more at www.diis.dk THE POLITICS OF OIL, GAS CONTRACT NEGOTIATIONS IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA By: Rasmus Hundsbæk Pedersen, DIIS, 2014 SUMMARY Much attention has been paid to the management of revenues from petroleum resources in Sub-Saharan Africa. An entire body of literature on the resource curse has developed which points to corruption during the negotiation of contracts, as well as the mismanagement of revenues on the continent. The analyses provide the basis for policy advice for countries as well as donors; transparency and anti- corruption initiatives aimed at lifting the curse flourish. Though this paper is sympathetic to these initiatives, it argues that the analysis may underestimate the inherently political nature of the negotiation of contracts. Based on a review of the existing literature on contract negotiations in Africa, combined with a case study of Tanzania, the paper argues that the resource curse need not hit all countries on the African continent. By focusing on changes in the relative bargaining strength of actors involved in negotiating processes, it points to the choices and trade-offs that invariably affect the terms and conditions of exploration and production activities. Whereas international oil companies are often depicted as being in the driving seat, the last decade’s high oil prices may have shifted power in governments’ favor. Though their influence has declined, donors may still want to influence oil and gas politics under these circumstances. -

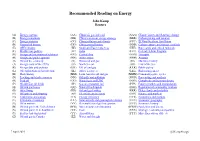

Recommended Reading on Energy

Recommended Reading on Energy John Kemp Reuters (A) Energy systems (AA) China oil, gas and coal (AAA) Climate issues and planetary change (B) Energy transitions (BB) China’s overseas energy strategy (BBB) Carbon pricing and taxation (C) Energy statistics (CC) China pollution and climate (CCC) El Nino/Southern Oscillation (D) General oil history (DD) China general history (DDD) Carbon capture and storage, synfuels (E) OPEC history (EE) South and East China Seas (EEE) Rare earths and critical minerals (F) Middle East politics (FF) India (FFF) Federal Helium Program (G) Energy and international relations (GG) Central Asia (GGG) Transport (H) Energy and public opinion (HH) Arctic issues (HHH) Aviation (I) Oil and the economy (II) Russia oil and gas (III) Maritime history (J) Energy crisis of the 1970s (JJ) North Sea oil (JJJ) Law of the Sea (K) Energy data and analysis (KK) UK oil and gas (KKK) Public policy (L) Oil exploration and production (LL) Africa resources (LLL) Risk management (M) Shale history (MM) Latin America oil and gas (MMM) Commodity price cycles (N) Fracking and shale resources (NN) Oil spills and pollution (NNN) Forecasting and analysis (O) Peak oil (OO) Natural gas and LNG (OOO) Complexity and systems theory (P) Middle East oil fields (PP) Gas as a transport fuel (PPP) Futures markets and manipulation (Q) Oil and gas leases (QQ) Natural Gas Liquids (QQQ) Regulation of commodity markets (R) Oil refining (RR) Oil and gas lending (RRR) Hedge funds and volatility (S) Oil tankers and shipping (SS) Electricity and security (SSS) Finance and markets (T) Tank farms and storage (TT) Energy efficiency (TTT) Economics and markets (U) Petroleum economics (UU) Solar activity and geomagnetic storms (UUU) Economic geography (V) Oil in wartime (VV) Renewables and grid integration (VVV) Economic history (W) Oil and gas in the United States (WW) Nuclear power and weapons (WWW) Epidemics and disease (X) Oil and gas in U.S. -

Introduction Continuity and Change in Venezuela’S Petro-Diplomacy

Introduction Continuity and Change in Venezuela’s Petro-Diplomacy Ralph S. Clem and Anthony P. Maingot Over the last decade, Venezuela has exerted an influence on the Western Hemisphere and indeed, global international relations, well beyond what one might expect from a country of 26.5 million people. In considering the reasons for this influence, one must of course take into account the country’s vast petroleum deposits. The wealth these generate, used traditionally to fi- nance national priorities, more recently has been heavily deployed to bolster Venezuela’s ambitious “Bolivarian”proof foreign policy. As with any country whose national income depends so heavily on export earnings from a single natural resource, Venezuela’s economic fate rests on its capacity to exploit that resource and, perhaps even more so, on the price set by the international market. The Venezuelan author Fernando Coronil calls this condition the “neo-colonial disease.” Without oil, there would be no Chávez, and certainly no “socialism of the twenty-first century.”1 Unpredict- ability is the signal character of the Venezuelan economy, and, consequently, no domestic or foreign policy assessments can be completely time-based. Nothing exemplifies this volatility better than the price of a barrel of oil, which was $148 when we began planning this collection of essays in mid- 2007, but which fell to less than $50, then climbed back to $70 by mid-2009. Instead of using a time-based approach, therefore, the essays in this volume attempt to trace the deep-rooted and enduring orientations of Venezuelan political culture and their influence on foreign policy, with special attention to the historical role petroleum has played in these considerations. -

The Oil Factor in Hugo Chávez's Foreign Policy

The Oil Factor in Hugo Chávez’s Foreign Policy Oil Abundance, Chavismo and Diplomacy C.C. Teske (s1457616) Research Master Thesis Research Master Latin American Studies Leiden University June, 2018 Thesis supervisor: Prof. dr. P. Silva Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Different thoughts on oil abundance in relation to populism and foreign policy 3 1.1 The academic debate around natural resource abundance leading towards the resource curse debate 4 1.2 The resource curse debate regarding populism and oil abundance from an international perspective 8 1.3 The International Political Economy and Robert Cox’s Method 14 Chapter 2 A historical perspective on oil abundance, foreign policy and the roots of chavismo 20 2.1 Venezuela before the oil era: caudillismo and agriculture 21 2.2 Oil and dictatorship: the beginning of the oil era 22 2.3 Oil and military rule: Venezuela becoming the world’s largest exporter of oil 26 2.4 Oil and democracy: Pacto de Punto Fijo and increasing US interference 28 2.5 Oil and socialism: the beginning of the Chávez era 31 2.6 The roots of chavismo in the Venezuelan history regarding oil abundance and international affairs 32 Chapter 3 The relationship between chavismo, oil abundance and Venezuela’s foreign policy during the presidency of Hugo Chávez 36 3.1 The Venezuelan domestic policy during the Chávez administration 37 3.2 The Venezuelan foreign policy during the Chávez administration 41 Conclusion 51 Bibliography 53 Introduction Ever since the exploitation of its oil Venezuela had not been able to live without this black gold. -

The Best of Times? Petroleum Politics in Canada

The Best of Times? Petroleum Politics in Canada Annual Meeting of the Canadian Political Science Assoication Draft Only – Not for Quotation Halifax, May 2003 Keith Brownsey Mount Royal College Calgary, Alberta 1. Introduction: It is the best of times for the Canadian oil and gas industry. As natural gas and oil prices have risen over the past two years petroleum companies have seen their profits increase dramatically.1 Domestic exploration is at unprecedented levels and investment in convention oil and gas production is increasing. It is also the worst of times for Canada’s oil and gas industry. Uncertainty, competition, and costs have created a situation of mounting uncertainty. Prices for oil and gas remain unstable, foreign investments are subject to increasing domestic and international scrutiny, aboriginal land claims threaten to disrupt domestic exploration and production, and the Kyoto Protocol to the United nations Framework Concention on Climate Change2 posses extra costs in an increasingly competitive world market for oil. Reserves in the Atlantic Offshore, moreover, have proven to be more elusive while conventional supplies of oil and natural gas are in decline and the massive reserves of the oil sands and heavy oil in western Canada have proven to be far more expensive to recover than oil from the middle east. The present may be profitable but the future holds little promise. The political-economic situation of uncertainty is framed within the context of competing ideologies and policies of the federal and producing provinces. The most contentious issue within the Canadian oil and gas industry is the Kyoto Protocol To The United Nations Framework Convention On Climate Change. -

Appendix I Chronology of Events

Appendix I Chronology of Events 1908: Oil is discovered in Persia by a syndicate of the Burmah Oil Company, the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC) 1911: United States Supreme Court orders the dissolution of Standard Oil Trust 1914: The British government purchases a majority holding in APOC 1914-18: World War I and the mechanisation of the battlefield 1920-23: The British government considers selling its holding in APOC 1922-28: Negotiation of the 'Red Line' and the 'As-Is' agreements 1932-33: Shah Reza Pahlavi cancels Anglo-Iranian Oil Company's (AIOC) con cession; AIOC wins it back 1934: AIOC and Gulf gain joint concession in Kuwait 1938: Mexico nationalises its oil companies 1939-45: World War II 1950: Fifty-fifty (participation) agreement between Aramco and Saudi Arabia 1950: Mohammed Mossadegh nationalises AIOC assets in Iran 1951-53: Korean War 1953: Mossadegh is overthrown and the Shah returns to power. The manage ment of Iraqi oil operations is contracted to an international consortium and AIOC obtains a 40 per cent majority stake Reports surface that the Conservative government is to dispose of its 56 per cent holding in AIOC 1956: Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt announces the appropriation of the Suez canal 1957: European Economic Community established 1960: Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries founded in Baghdad 1964: First round licences are awarded for exploration in the North Sea by the Department of Trade and Industry 1965: British Petroleum (BP) discovers gas in the North Sea 1965: Britain imposes sanctions -

Linking China's Energy Strategy with Venezuela

Linking China’s Energy Strategy with Venezuela: Transnationalization of Chinese NOCs and Geopolitical Implication of China-Venezuela Relations Author: Changwei Tang (10866825) Supervisor: Dr. M. (Mehdi) Parvizi Amineh Second Reader: Prof. Dr. Kurt Radtke Date: 26th June 2015 Master Thesis Political Science: International Relations Research Project: Political Economy of Energy 1 Table of Content Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgement .................................................................................................................... 5 Maps of the Selected Countries .............................................................................................. 6 List of Figures and Tables ....................................................................................................... 8 List of Abbreviations ............................................................................................................... 9 Chapter 1. Research Design .................................................................................................. 10 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 12 1.2 Literature Review .................................................................................................................................... 12 1.2.1 Chinese Energy Security ........................................................................................................... -

Thesis?’, T Asked, As We Were Chatting on Facebook an Evening in August, a Few Months Before My Thesis Was Due

Making Resource Futures: Petroleum and Performance by the Norwegian Barents Sea Ragnhild Freng Dale Hughes Hall November 2018 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Scott Polar Research Institute University of Cambridge ‘Will I appear in your thesis?’, T asked, as we were chatting on Facebook an evening in August, a few months before my thesis was due. I told him I have anonymised everyone, though he was still there, somewhere, which I hoped was ok. So to T, and everyone I have met during my fieldwork: I hope that you can recognise the perspectives I describe and that they reflect some of the home region you know and live in. I also hope I might surprise you; that on these pages, if you come to read them, you might find new or unfamiliar perspectives, and see some of the overlapping worlds that are woven together with your own. And I hope we meet again soon, outside of my fieldwork notes. 2 Declaration This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. -

Learning Geopolitical Pluralism: Toward a New International Oil Regime? 1 Clement M

Chapter 1 Learning Geopolitical Pluralism: Toward a New International Oil Regime? 1 Clement M. Henry The Middle East can be viewed as Hell’s kitchen, depositary of most of the world’s most cheaply accessed oil that accounts for much of our global warming. Given its environmental impact, somehow containing its production and distribution must surely be a priority for any political ecology of the region. The Middle East is also viewed by many as a geopolitical prize astride three continents, now sharply contested and fragmented by proxy wars in Libya, Syria, and Yemen reflecting a painful readjustment of the global balance that empowers regional rivalries. While the local conflicts are not about oil, the imputed strategic value of the commodity has reinforced the region’s geopolitical significance as an arena for competition among great powers. Political ecology (the third paradigm proposed in the introduction to this book) may suggest, however, that oil be viewed as just another commodity without any special strategic value. Was “securing oil” not simply a construct to buttress the US military industrial complex and to legitimate the United States protecting the Free World and pressuring potential adversaries?2 Yet overemphasizing this narrative risks overlooking not only how oil has been a key material factor in state formation and nation building in the last century (as explained in the volume's introduction), but also how under the shadow of Anglo-American hegemony the oil producers managed to control production first in Texas and then in the whole of the non-Soviet world. In response to an oil glut in the early 1930s, when the price of oil dropped to under 10 cents a barrel, the Texas Railroad Commission acquired the authority to prorate production. -

Will Oil Prices Decline Over the Long Run?

OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES NO 98 / OCTOBER 2008 WILL OIL PRICES DECLINE OVER THE LONG RUN? by Robert Kaufmann, Pavlos Karadeloglou and Filippo di Mauro OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES NO 98 / OCTOBER 2008 WILL OIL PRICES DECLINE OVER THE LONG RUN? 1 by Robert Kaufmann 1, 2, Pavlos Karadeloglou 3 and Filippo di Mauro 4 In 2008 all ECB publications This paper can be downloaded without charge from feature a motif taken from the http://www.ecb.europa.eu or from the Social Science Research Network €10 banknote. electronic library at http://ssrn.com/abstract_id=1144485. 1 The authors would like to thank H.-J. Klöckers, L. Hermans, A. Meyler and an anonymous referee for their helpful comments. The substantial input from M. Lombardi on the role of speculation is gratefully acknowledged. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and may not necessarily reflect the views of the European Central Bank. 2 Boston University. 3 External Developments Division European Central Bank, [email protected]. 4 External Developments Division European Central Bank, [email protected]. © European Central Bank, 2008 Address Kaiserstrasse 29 60311 Frankfurt am Main Germany Postal address Postfach 16 03 19 60066 Frankfurt am Main Germany Telephone +49 69 1344 0 Website http://www.ecb.europa.eu Fax +49 69 1344 6000 All rights reserved. Any reproduction, publication or reprint in the form of a different publication, whether printed or produced electronically, in whole or in part, is permitted only with the explicit written authorisation of the ECB or the author(s). The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily refl ect those of the European Central Bank. -

A Scan of the Long-Distance Oil Pipeline Research Literature: a Focus on Canada

A scan of the long-distance oil pipeline research literature: A focus on Canada Elisabeth Belanzaran, Kevin Hanna, & Karaline Reimer Acknowledgements Support for this work was provided by the Pipeline Integrity Institute at the University of British Columbia. Suggested citation Belanzaran, E. Hanna, K. & Reimer, K. (2020). A scan of the long-distance oil pipeline research literature: A focus on Canada. Report by the Pipeline Integrity Institute and the Centre for Environmental Assessment. The University of British Columbia. Vancouver. Cover image Trans Mountain Expansion site in the Coldwater Valley, south central BC. Photo: K. Hanna. Table of Contents Summary i Introduction 1 Method and Approach 3 Results 7 Materials and related issues and practices 7 Steel alloys, engineering and testing of 7 novel materials Materials failures-corrosion and cracking 8 Detection methods and prediction models 8 Pipeline coatings 9 Failure prediction models 10 Design, construction, and operations 12 Flow dynamics 12 Geohazards 13 Permafrost and cold climate issues 14 Incidents 16 Predictive models 16 Pipeline integrity 17 Indigenous considerations 18 Public perception and social acceptance 20 Social acceptance 20 Studies of media and social media 21 coverage Economics 23 Political, policy, legal and regulatory issues 25 Ecological issues 28 Wildlife impacts and human dimensions of 28 wildlife management Soil properties 29 Conclusions and Recommendations 30 References 32 Appendix: References by Topic Heading 50 Summary This review, or scan, is a desk-based study that provides a synopsis and list of what has been done and where areas of research concentration exist – it offers an image of the state of existing work with a focus on those works that have relevance to the Canadian setting, which included works on a North American topic or case.