The Oil Factor in Hugo Chávez's Foreign Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geopolitics, Oil Law Reform, and Commodity Market Expectations

OKLAHOMA LAW REVIEW VOLUME 63 WINTER 2011 NUMBER 2 GEOPOLITICS, OIL LAW REFORM, AND COMMODITY MARKET EXPECTATIONS ROBERT BEJESKY * Table of Contents I. Introduction .................................... ........... 193 II. Geopolitics and Market Equilibrium . .............. 197 III. Historical U.S. Foreign Policy in the Middle East ................ 202 IV. Enter OPEC ..................................... ......... 210 V. Oil Industry Reform Planning for Iraq . ............... 215 VI. Occupation Announcements and Economics . ........... 228 VII. Iraq’s 2007 Oil and Gas Bill . .............. 237 VIII. Oil Price Surges . ............ 249 IX. Strategic Interests in Afghanistan . ................ 265 X. Conclusion ...................................... ......... 273 I. Introduction The 1973 oil supply shock elevated OPEC to world attention and ensconced it in the general consciousness as a confederacy that is potentially * M.A. Political Science (Michigan), M.A. Applied Economics (Michigan), LL.M. International Law (Georgetown). The author has taught international law courses for Cooley Law School and the Department of Political Science at the University of Michigan, American Government and Constitutional Law courses for Alma College, and business law courses at Central Michigan University and the University of Miami. 193 194 OKLAHOMA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 63:193 antithetical to global energy needs. From 1986 until mid-1999, prices generally fluctuated within a $10 to $20 per barrel band, but alarms sounded when market prices started hovering above $30. 1 In July 2001, Senator Arlen Specter addressed the Senate regarding the need to confront OPEC and urged President Bush to file an International Court of Justice case against the organization, on the basis that perceived antitrust violations were a breach of “general principles of law.” 2 Prices dipped initially, but began a precipitous rise in mid-March 2002. -

Cryptocurrency: the Economics of Money and Selected Policy Issues

Cryptocurrency: The Economics of Money and Selected Policy Issues Updated April 9, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45427 SUMMARY R45427 Cryptocurrency: The Economics of Money and April 9, 2020 Selected Policy Issues David W. Perkins Cryptocurrencies are digital money in electronic payment systems that generally do not require Specialist in government backing or the involvement of an intermediary, such as a bank. Instead, users of the Macroeconomic Policy system validate payments using certain protocols. Since the 2008 invention of the first cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, cryptocurrencies have proliferated. In recent years, they experienced a rapid increase and subsequent decrease in value. One estimate found that, as of March 2020, there were more than 5,100 different cryptocurrencies worth about $231 billion. Given this rapid growth and volatility, cryptocurrencies have drawn the attention of the public and policymakers. A particularly notable feature of cryptocurrencies is their potential to act as an alternative form of money. Historically, money has either had intrinsic value or derived value from government decree. Using money electronically generally has involved using the private ledgers and systems of at least one trusted intermediary. Cryptocurrencies, by contrast, generally employ user agreement, a network of users, and cryptographic protocols to achieve valid transfers of value. Cryptocurrency users typically use a pseudonymous address to identify each other and a passcode or private key to make changes to a public ledger in order to transfer value between accounts. Other computers in the network validate these transfers. Through this use of blockchain technology, cryptocurrency systems protect their public ledgers of accounts against manipulation, so that users can only send cryptocurrency to which they have access, thus allowing users to make valid transfers without a centralized, trusted intermediary. -

Estimating the Energy Security Benefits of Reduced U.S. Oil Imports1

ORNL/TM-2007/028 Estimating the Energy Security Benefits of Reduced U.S. Oil Imports1 Final Report Paul N. Leiby Oak Ridge National Laboratory Oak Ridge, Tennessee [email protected] Revised March 14, 2008 Prepared by OAK RIDGE NATIONAL LABORATORY Oak Ridge, Tennessee 37831 Managed by UT-BATTELLE for the U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY under contract DE-AC05-00OR22725 1We are enormously grateful for the careful review and helpful comments offered by a review panel including Joseph E. Aldy, Resources for the Future, Stephen P. A. Brown, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Dermot Gately, New York University, Hillard G. Huntington, Energy Modeling Forum and Stanford University, Mike Toman, Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University, and Mine Yücel, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. Additional helpful suggestions were offered by Edmund Coe, Jefferson Cole and Michael Shelby, U.S. EPA, and Gbadebo Oladosu and David Greene, Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Naturally the views and conclusions offered are the responsibility of the author. This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. -

Petroleum Politics: China and Its National Oil Companies

MASTER IN ADVANCED EUROPEAN AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES ANGLOPHONE BRANCH - Academic year 2012/2013 Master Thesis Petroleum Politics: China and Its National Oil Companies By Ellennor Grace M. FRANCISCO 26 June 2013 Supervised by: Dr. Laurent BAECHLER Deputy Director MAEIS To Whom I owe my willing and my running CONTENTS List of Tables and Figures v List of Abbreviations vi Chapter 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Literature Review 2 1.2 Methodologies 4 1.3 Objectives and Scope 4 Chapter 2. Historical Evolution of Chinese National Oil Companies 6 2.1 The Central Government and “Self-Reliance” (1950- 1977) 6 2.2 Breakdown and Corporatization: First Reform (1978- 1991) 7 2.3 Decentralization: Second Reform (1992- 2003) 11 2.4 Government Institutions and NOCs: A Move to Recentralization? (2003- 2010) 13 2.5 Corporate Governance, Ownership and Marketization 15 2.5.1 International Market 16 2.5.2 Domestic Market 17 Chapter 3. Chinese Politics and NOC Governance 19 3.1 CCP’s Controlling Mechanisms 19 3.1.1 State Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) 19 3.1.2 Central Organization Department 21 3.2 Transference Between Government and Corporate Positions 23 3.3 Traditional Connections and the Guanxi 26 3.4 Convergence of NOC Politics 29 Chapter 4. The “Big Four”: Overview of the Chinese Banking Sector 30 Preferential Treatment 33 Chapter 5. Oil Security and The Going Out Policy 36 5.1 The Policy Driver: Equity Oil 36 5.2 The Going Out Policy (zou chu qu) 37 5.2.1 The Development of OFDI and NOCs 37 5.2.2 Trends of Outward Foreign Investments 39 5.3 State Financing: The Chinese Policy Banks 42 5.4 Loans for Oil 44 Chapter 6. -

“El Fenomeno Chavez:” Hugo Chavez of Venezuela, Modern Day Bolivar

“El Fenomeno Chavez:” Hugo Chavez of Venezuela, Modern Day Bolivar Jerrold M. Post US Air Force Counterproliferation Center 39 Future Warfare Series No. 39 “El Fenomeno Chavez:” Hugo Chavez of Venezuela, Modern Day Bolivar by Jerrold M. Post The Counterproliferation Papers Future Warfare Series No. 39 USAF Counterproliferation Center Air University Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama “El Fenomeno Chavez:” Hugo Chavez of Venezuela, Modern Day Bolivar Jerrold M. Post March 2007 The Counterproliferation Papers Series was established by the USAF Counterproliferation Center to provide information and analysis to assist the understanding of the U.S. national security policy-makers and USAF officers to help them better prepare to counter the threat from weapons of mass destruction. Copies of No. 39 and previous papers in this series are available from the USAF Counterproliferation Center, 325 Chennault Circle, Maxwell AFB AL 36112-6427. The fax number is (334) 953- 7530; phone (334) 953-7538. Counterproliferation Paper No. 39 USAF Counterproliferation Center Air University Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama 36112-6427 The Internet address for the USAF Counterproliferation Center is: http://cpc.au.af.mil/ Contents Page Disclaimer........................................................................................................ ii About the Author ............................................................................................ iii Executive Summary ..........................................................................................v -

Opec from Myth to Reality

CUERVO FINAL 4/23/2008 12:19:35 PM OPEC FROM MYTH TO REALITY Luis E. Cuervo* I. INTRODUCTION—THE IMPORTANCE OF ENERGY SECURITY, RESOURCE DIPLOMACY, AND THE MAIN CHANGES IN NEARLY HALF A CENTURY OF OPEC’S FORMATION ....................................................................... 436 A. Energy Dependency, Foreign Policy,and the U.S. Example ....................................................... 442 B. Some of the Major Changes in the Oil and Gas Industry Since OPEC’s Formation............................ 452 C. Oil and Gas Will Be the Dominant Energy Sources for at Least Two More Generations........................... 455 D. A New OPEC in an International Environment in Which the End of the Hydrocarbon Era Is in Sight . 458 II. ARE OPEC’S GOALS AND STRUCTURE OUTDATED IN VIEW OF THE EMERGENT TRENDS IN THE INTERNATIONAL ENERGY INDUSTRY?............................... 464 A. OPEC’s Formation and Goals................................... 464 B. Significant International Developments Since OPEC’s Formation..................................................... 471 1. Permanent Sovereignty Over Natural Resources and a New International Economic Order .......... 473 * Professor Cuervo is a member of the Texas, Louisiana, and Colombian Bar Associations. He is a Fulbright Scholar and Tulane Law School graduate. Mr. Cuervo has taught Oil and Gas Law and International Petroleum Transactions as an adjunct professor at Tulane Law School and the University of Houston Law Center. He served as an advisor to the Colombian Ministry of Justice and to OPEC. Mr. Cuervo practices law in Houston, Texas as a partner with Fowler, Rodriguez. This paper was prepared for and delivered to OPEC in December 2006. Its contents represent only the Author’s views and not those of OPEC. 433 CUERVO FINAL 4/23/2008 12:19:35 PM 434 HOUSTON JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW [Vol. -

Do Blockchain Technologies Make Us Safer? Do Cryptocurrencies Necessarily Make Us Less Safe?

Maurer School of Law: Indiana University Digital Repository @ Maurer Law Articles by Maurer Faculty Faculty Scholarship 2020 Do Blockchain Technologies Make Us Safer? Do Cryptocurrencies Necessarily Make Us Less Safe? Sarah Jane Hughes Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons, and the Internet Law Commons 55 Tex. Int’l L. J. 373 Do Blockchain Technologies Make Us Safer? Do Cryptocurrencies Necessarily Make Us Less Safe? SARAH JANE HUGHES* Abstract This essay is based on a presentation made on January 24, 2020 at the invitation of the Texas Journal of International Law and the Strauss Center for National Security at the University of Texas. That presentation focused on the two questions mentioned in the title of this essay – Do Blockchain Technologies Make Us Safer? And Do Cryptocurrencies Necessarily Make Us Less Safe? The essay presents answers to the two questions: “yes” and “probably yes.” This essay begins with some level-setting on different types of blockchain technologies and of cryptocurrencies, and gives some background materials on global and national responses to certain cryptocurrencies, such as El Petro sponsored by Venezuela’s PDVSA and Facebook’s Libra. * Sarah Jane Hughes is the University Scholar and Fellow in Commercial Law at the Maurer School of Law, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana. She served as the Reporter for the Uniform Law Commission’s Uniform Regulation of Virtual-Currency Businesses Act (2017) and the Uniform Supplemental Commercial Law for the Uniform Regulation of Virtual-Currency Businesses Act (2018). Support for this paper came from the Maurer School of Law and from the Program on Financial Regulation & Technology, Law & Economics Center, George Mason University’s Antonin Scalia School of Law. -

The Politics of Oil, Gas Contract Negotiations in Sub-Saharan Africa

The politics of oil, gas contract negotiations in Sub-Saharan Africa This article is part of DIIS Report 2014:25 “Policies and finance for economic development and trade” Read more at www.diis.dk THE POLITICS OF OIL, GAS CONTRACT NEGOTIATIONS IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA By: Rasmus Hundsbæk Pedersen, DIIS, 2014 SUMMARY Much attention has been paid to the management of revenues from petroleum resources in Sub-Saharan Africa. An entire body of literature on the resource curse has developed which points to corruption during the negotiation of contracts, as well as the mismanagement of revenues on the continent. The analyses provide the basis for policy advice for countries as well as donors; transparency and anti- corruption initiatives aimed at lifting the curse flourish. Though this paper is sympathetic to these initiatives, it argues that the analysis may underestimate the inherently political nature of the negotiation of contracts. Based on a review of the existing literature on contract negotiations in Africa, combined with a case study of Tanzania, the paper argues that the resource curse need not hit all countries on the African continent. By focusing on changes in the relative bargaining strength of actors involved in negotiating processes, it points to the choices and trade-offs that invariably affect the terms and conditions of exploration and production activities. Whereas international oil companies are often depicted as being in the driving seat, the last decade’s high oil prices may have shifted power in governments’ favor. Though their influence has declined, donors may still want to influence oil and gas politics under these circumstances. -

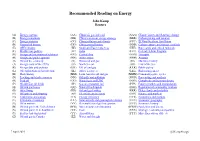

Recommended Reading on Energy

Recommended Reading on Energy John Kemp Reuters (A) Energy systems (AA) China oil, gas and coal (AAA) Climate issues and planetary change (B) Energy transitions (BB) China’s overseas energy strategy (BBB) Carbon pricing and taxation (C) Energy statistics (CC) China pollution and climate (CCC) El Nino/Southern Oscillation (D) General oil history (DD) China general history (DDD) Carbon capture and storage, synfuels (E) OPEC history (EE) South and East China Seas (EEE) Rare earths and critical minerals (F) Middle East politics (FF) India (FFF) Federal Helium Program (G) Energy and international relations (GG) Central Asia (GGG) Transport (H) Energy and public opinion (HH) Arctic issues (HHH) Aviation (I) Oil and the economy (II) Russia oil and gas (III) Maritime history (J) Energy crisis of the 1970s (JJ) North Sea oil (JJJ) Law of the Sea (K) Energy data and analysis (KK) UK oil and gas (KKK) Public policy (L) Oil exploration and production (LL) Africa resources (LLL) Risk management (M) Shale history (MM) Latin America oil and gas (MMM) Commodity price cycles (N) Fracking and shale resources (NN) Oil spills and pollution (NNN) Forecasting and analysis (O) Peak oil (OO) Natural gas and LNG (OOO) Complexity and systems theory (P) Middle East oil fields (PP) Gas as a transport fuel (PPP) Futures markets and manipulation (Q) Oil and gas leases (QQ) Natural Gas Liquids (QQQ) Regulation of commodity markets (R) Oil refining (RR) Oil and gas lending (RRR) Hedge funds and volatility (S) Oil tankers and shipping (SS) Electricity and security (SSS) Finance and markets (T) Tank farms and storage (TT) Energy efficiency (TTT) Economics and markets (U) Petroleum economics (UU) Solar activity and geomagnetic storms (UUU) Economic geography (V) Oil in wartime (VV) Renewables and grid integration (VVV) Economic history (W) Oil and gas in the United States (WW) Nuclear power and weapons (WWW) Epidemics and disease (X) Oil and gas in U.S. -

Historia De Las Ideas En Venezuela

HISTORIA DE LAS IDEAS EN VENEZUELA DAVID RUIZ CHATAING Universidad Metropolitana, Caracas, Venezuela, 2017 Hecho el depósito de Ley Depósito Legal: ISBN: Formato: 15,5 x 21,5 cms. Nº de páginas: 228 Diseño y diagramación: Jesús Salazar / [email protected] Autoridades Hernán Anzola Presidente del Consejo Superior Benjamín Scharifker Rector Mercedes de la Oliva Vicerrectora Académica María Elena Cedeño Vicerrectora Administrativa María del Carmen Lombao Secretario General Comité Editorial de Publicaciones de apoyo a la educación Prof. Roberto Réquiz Prof. Natalia Castañón Prof. Mario Eugui Prof. Humberto Njaim Prof. Rosana París Prof. Alfredo Rodríguez Iranzo (Editor) CONTENIDO RESUMEN 4 INTRODUCCIÓN 5 CAPÍTULO I. Eduardo Calcaño o de la compleja relación entre el intelectual y el poder 7 1. Vida y obra 7 2. El intelectual y el poder 13 CAPÍTULO II. Pensamiento cristiano-católico en Venezuela. Los casos de Amenodoro Urdaneta Vargas y José Manuel Núñez Ponte 21 1. Pensamiento cristiano en Venezuela 21 2. Vida y obra de Amenodoro Urdaneta 22 3. Vida y Obra de José Manuel Núñez Ponte 24 4. La fe y la ciencia 27 5. Religión cristiana y política 28 6. La concepción de la Historia 30 7. Contra las ideologías violentas 31 8. Republicanos, liberales, federalista y demócratas 33 9. La patria y el patriotismo 36 10. Venezuela enferma 37 11. La educación como solución 39 CAPÍTULO III. Juvenal Anzola o el optimismo a toda prueba 44 1. Vida y obra 44 2. Ante la guerra 48 3. Educación para cambiar las costumbres 50 4. Idea de la política 52 5. La caminomanía 55 CAPÍTULO IV. -

OFAC Sanctions Considerations for the Crypto Sector

OFAC Sanctions Considerations for the Crypto Sector August 17, 2021 AUTHORS Britt Mosman | David Mortlock | Elizabeth P. Gray | J. Christopher Giancarlo Samuel Hall In recent years, the U.S. government has become increasingly focused on regulating the use of virtual currencies as a means of addressing a host of financial crimes and malign activities. As entities and individuals (“persons”) in this space find themselves subject to various, sometimes overlapping regulatory regimes, the compliance environment has become increasingly treacherous. One area of particular concern for those dealing with cryptocurrencies is U.S. economic sanctions, as is evidenced by the recent settlement between the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”) and BitPay Inc. (“BitPay”), discussed below. Indeed, sanctions hold some of the most complicated compliance issues in one hand, and some of the largest penalties in the other, and they do not always—or perhaps rarely—fit cryptocurrency transactions neatly. This alert provides an overview of sanctions compliance principles for the cryptocurrency industry and discusses some key issues of which persons in the crypto space should be mindful, including: Sanctioned coins, persons, and regions; Restricted transactions; and Recommendations for compliance. Willkie Farr & Gallagher LLP | willkie.com 1 OFAC Sanctions Considerations for the Crypto Sector As this alert makes clear, some of the relevant prohibitions remain ambiguous and leave significant questions unanswered. In turn, some crypto transactions and related regulations may warrant license and guidance requests to OFAC or even legal challenges, including Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”) challenges, in U.S. courts to resolve those ambiguities. But at a minimum, there are certain basic steps that should be taken to comply with U.S. -

Introduction Continuity and Change in Venezuela’S Petro-Diplomacy

Introduction Continuity and Change in Venezuela’s Petro-Diplomacy Ralph S. Clem and Anthony P. Maingot Over the last decade, Venezuela has exerted an influence on the Western Hemisphere and indeed, global international relations, well beyond what one might expect from a country of 26.5 million people. In considering the reasons for this influence, one must of course take into account the country’s vast petroleum deposits. The wealth these generate, used traditionally to fi- nance national priorities, more recently has been heavily deployed to bolster Venezuela’s ambitious “Bolivarian”proof foreign policy. As with any country whose national income depends so heavily on export earnings from a single natural resource, Venezuela’s economic fate rests on its capacity to exploit that resource and, perhaps even more so, on the price set by the international market. The Venezuelan author Fernando Coronil calls this condition the “neo-colonial disease.” Without oil, there would be no Chávez, and certainly no “socialism of the twenty-first century.”1 Unpredict- ability is the signal character of the Venezuelan economy, and, consequently, no domestic or foreign policy assessments can be completely time-based. Nothing exemplifies this volatility better than the price of a barrel of oil, which was $148 when we began planning this collection of essays in mid- 2007, but which fell to less than $50, then climbed back to $70 by mid-2009. Instead of using a time-based approach, therefore, the essays in this volume attempt to trace the deep-rooted and enduring orientations of Venezuelan political culture and their influence on foreign policy, with special attention to the historical role petroleum has played in these considerations.