ANALYZING GLOBAL INTERDEPENDENCE by Hayward R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Petroleum Politics: China and Its National Oil Companies

MASTER IN ADVANCED EUROPEAN AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES ANGLOPHONE BRANCH - Academic year 2012/2013 Master Thesis Petroleum Politics: China and Its National Oil Companies By Ellennor Grace M. FRANCISCO 26 June 2013 Supervised by: Dr. Laurent BAECHLER Deputy Director MAEIS To Whom I owe my willing and my running CONTENTS List of Tables and Figures v List of Abbreviations vi Chapter 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Literature Review 2 1.2 Methodologies 4 1.3 Objectives and Scope 4 Chapter 2. Historical Evolution of Chinese National Oil Companies 6 2.1 The Central Government and “Self-Reliance” (1950- 1977) 6 2.2 Breakdown and Corporatization: First Reform (1978- 1991) 7 2.3 Decentralization: Second Reform (1992- 2003) 11 2.4 Government Institutions and NOCs: A Move to Recentralization? (2003- 2010) 13 2.5 Corporate Governance, Ownership and Marketization 15 2.5.1 International Market 16 2.5.2 Domestic Market 17 Chapter 3. Chinese Politics and NOC Governance 19 3.1 CCP’s Controlling Mechanisms 19 3.1.1 State Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) 19 3.1.2 Central Organization Department 21 3.2 Transference Between Government and Corporate Positions 23 3.3 Traditional Connections and the Guanxi 26 3.4 Convergence of NOC Politics 29 Chapter 4. The “Big Four”: Overview of the Chinese Banking Sector 30 Preferential Treatment 33 Chapter 5. Oil Security and The Going Out Policy 36 5.1 The Policy Driver: Equity Oil 36 5.2 The Going Out Policy (zou chu qu) 37 5.2.1 The Development of OFDI and NOCs 37 5.2.2 Trends of Outward Foreign Investments 39 5.3 State Financing: The Chinese Policy Banks 42 5.4 Loans for Oil 44 Chapter 6. -

The Politics of Oil, Gas Contract Negotiations in Sub-Saharan Africa

The politics of oil, gas contract negotiations in Sub-Saharan Africa This article is part of DIIS Report 2014:25 “Policies and finance for economic development and trade” Read more at www.diis.dk THE POLITICS OF OIL, GAS CONTRACT NEGOTIATIONS IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA By: Rasmus Hundsbæk Pedersen, DIIS, 2014 SUMMARY Much attention has been paid to the management of revenues from petroleum resources in Sub-Saharan Africa. An entire body of literature on the resource curse has developed which points to corruption during the negotiation of contracts, as well as the mismanagement of revenues on the continent. The analyses provide the basis for policy advice for countries as well as donors; transparency and anti- corruption initiatives aimed at lifting the curse flourish. Though this paper is sympathetic to these initiatives, it argues that the analysis may underestimate the inherently political nature of the negotiation of contracts. Based on a review of the existing literature on contract negotiations in Africa, combined with a case study of Tanzania, the paper argues that the resource curse need not hit all countries on the African continent. By focusing on changes in the relative bargaining strength of actors involved in negotiating processes, it points to the choices and trade-offs that invariably affect the terms and conditions of exploration and production activities. Whereas international oil companies are often depicted as being in the driving seat, the last decade’s high oil prices may have shifted power in governments’ favor. Though their influence has declined, donors may still want to influence oil and gas politics under these circumstances. -

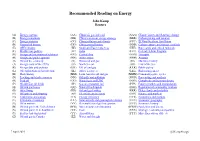

Recommended Reading on Energy

Recommended Reading on Energy John Kemp Reuters (A) Energy systems (AA) China oil, gas and coal (AAA) Climate issues and planetary change (B) Energy transitions (BB) China’s overseas energy strategy (BBB) Carbon pricing and taxation (C) Energy statistics (CC) China pollution and climate (CCC) El Nino/Southern Oscillation (D) General oil history (DD) China general history (DDD) Carbon capture and storage, synfuels (E) OPEC history (EE) South and East China Seas (EEE) Rare earths and critical minerals (F) Middle East politics (FF) India (FFF) Federal Helium Program (G) Energy and international relations (GG) Central Asia (GGG) Transport (H) Energy and public opinion (HH) Arctic issues (HHH) Aviation (I) Oil and the economy (II) Russia oil and gas (III) Maritime history (J) Energy crisis of the 1970s (JJ) North Sea oil (JJJ) Law of the Sea (K) Energy data and analysis (KK) UK oil and gas (KKK) Public policy (L) Oil exploration and production (LL) Africa resources (LLL) Risk management (M) Shale history (MM) Latin America oil and gas (MMM) Commodity price cycles (N) Fracking and shale resources (NN) Oil spills and pollution (NNN) Forecasting and analysis (O) Peak oil (OO) Natural gas and LNG (OOO) Complexity and systems theory (P) Middle East oil fields (PP) Gas as a transport fuel (PPP) Futures markets and manipulation (Q) Oil and gas leases (QQ) Natural Gas Liquids (QQQ) Regulation of commodity markets (R) Oil refining (RR) Oil and gas lending (RRR) Hedge funds and volatility (S) Oil tankers and shipping (SS) Electricity and security (SSS) Finance and markets (T) Tank farms and storage (TT) Energy efficiency (TTT) Economics and markets (U) Petroleum economics (UU) Solar activity and geomagnetic storms (UUU) Economic geography (V) Oil in wartime (VV) Renewables and grid integration (VVV) Economic history (W) Oil and gas in the United States (WW) Nuclear power and weapons (WWW) Epidemics and disease (X) Oil and gas in U.S. -

Introduction Continuity and Change in Venezuela’S Petro-Diplomacy

Introduction Continuity and Change in Venezuela’s Petro-Diplomacy Ralph S. Clem and Anthony P. Maingot Over the last decade, Venezuela has exerted an influence on the Western Hemisphere and indeed, global international relations, well beyond what one might expect from a country of 26.5 million people. In considering the reasons for this influence, one must of course take into account the country’s vast petroleum deposits. The wealth these generate, used traditionally to fi- nance national priorities, more recently has been heavily deployed to bolster Venezuela’s ambitious “Bolivarian”proof foreign policy. As with any country whose national income depends so heavily on export earnings from a single natural resource, Venezuela’s economic fate rests on its capacity to exploit that resource and, perhaps even more so, on the price set by the international market. The Venezuelan author Fernando Coronil calls this condition the “neo-colonial disease.” Without oil, there would be no Chávez, and certainly no “socialism of the twenty-first century.”1 Unpredict- ability is the signal character of the Venezuelan economy, and, consequently, no domestic or foreign policy assessments can be completely time-based. Nothing exemplifies this volatility better than the price of a barrel of oil, which was $148 when we began planning this collection of essays in mid- 2007, but which fell to less than $50, then climbed back to $70 by mid-2009. Instead of using a time-based approach, therefore, the essays in this volume attempt to trace the deep-rooted and enduring orientations of Venezuelan political culture and their influence on foreign policy, with special attention to the historical role petroleum has played in these considerations. -

Acomparative Study of Middle English Romance and Modern Popular Sheikh Romance

DESIRING THE EAST: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF MIDDLE ENGLISH ROMANCE AND MODERN POPULAR SHEIKH ROMANCE AMY BURGE PHD UNIVERSITY OF YORK WOMEN‟S STUDIES SEPTEMBER 2012 ABSTRACT This thesis comparatively examines a selection of twenty-first century sheikh romances and Middle English romances from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries that imagine an erotic relationship occurring between east and west. They do so against a background of conflict, articulated in military confrontation and binary religious and ethnic division. The thesis explores the strategies used to facilitate the cross-cultural relationship across such a gulf of difference and considers what a comparison of medieval and modern romance can reveal about attitudes towards otherness in popular romance. In Chapter 1, I analyse the construction of the east in each genre, investigating how the homogenisation of the romance east in sheikh romance distances it from the geopolitical reality of those parts of the Middle East seen, by the west, to be „other‟. Chapter 2 examines the articulation of gender identity and the ways in which these romances subvert and reassert binary gender difference to uphold normative heterosexual relations. Chapter 3 considers how ethnic and religious difference is nuanced, in particular through the use of fabric, breaking down the disjunction between east and west. Chapter 4 investigates the way ethnicity, religion and gender affect hierarchies of power in the abduction motif, enabling undesirable aspects of the east to be recast. The key finding of this thesis is that both romance genres facilitate the cross-cultural erotic relationship by rewriting apparently binary differences of religion and ethnicity to create sameness. -

Building Bridges

BUILDING BRIDGES SUMMARY REPORT An Initiative by BUILDING BRIDGES SUMMARY REPORT SOLAR ENERGY FOR SCIENCE SYMPOSIUM 19/20 MAY 2011 DESY HAMBURG www.solar4science.de 4 5 INDEX Executive Summary ...................................................................................... 5 Preface .......................................................................................................... 6 Editorial ......................................................................................................... 8 Reports on Sessions: Opening Session ......................................................................................... 10 Government Panel ...................................................................................... 16 Renewable Energy, Climate Change and Societal Challenges .................... 24 Science, Sustainability and Global Responsibility ........................................ 32 Solar Energy Projects in Europe and MENA ................................................. 40 Bridging Solar Energy from MENA to Europe ............................................... 50 Solar Energy Projects around the World ...................................................... 58 Academic/Educational Projects in MENA..................................................... 64 Scientific Projects in MENA ......................................................................... 70 Round Table Discussion .............................................................................. 78 Conclusions ................................................................................................ -

The Oil Factor in Hugo Chávez's Foreign Policy

The Oil Factor in Hugo Chávez’s Foreign Policy Oil Abundance, Chavismo and Diplomacy C.C. Teske (s1457616) Research Master Thesis Research Master Latin American Studies Leiden University June, 2018 Thesis supervisor: Prof. dr. P. Silva Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Different thoughts on oil abundance in relation to populism and foreign policy 3 1.1 The academic debate around natural resource abundance leading towards the resource curse debate 4 1.2 The resource curse debate regarding populism and oil abundance from an international perspective 8 1.3 The International Political Economy and Robert Cox’s Method 14 Chapter 2 A historical perspective on oil abundance, foreign policy and the roots of chavismo 20 2.1 Venezuela before the oil era: caudillismo and agriculture 21 2.2 Oil and dictatorship: the beginning of the oil era 22 2.3 Oil and military rule: Venezuela becoming the world’s largest exporter of oil 26 2.4 Oil and democracy: Pacto de Punto Fijo and increasing US interference 28 2.5 Oil and socialism: the beginning of the Chávez era 31 2.6 The roots of chavismo in the Venezuelan history regarding oil abundance and international affairs 32 Chapter 3 The relationship between chavismo, oil abundance and Venezuela’s foreign policy during the presidency of Hugo Chávez 36 3.1 The Venezuelan domestic policy during the Chávez administration 37 3.2 The Venezuelan foreign policy during the Chávez administration 41 Conclusion 51 Bibliography 53 Introduction Ever since the exploitation of its oil Venezuela had not been able to live without this black gold. -

A Symbolic Beginning As the Friendship Tour Is Launched from Bahrain’S Formula-1 Circuit

STAGE ONE A SYMBOLIC BEGINNING AS THE FRIENDSHIP TOUR IS LAUNCHED FROM BAHRain’s foRMULa-1 cirCUIT Where’s About Bahrain Visa Requirements Getting There Interesting Fact Dilmun? Bahrain is an archipp Visas are required for Bahrain is well conp Bahrain is the pelago of 33 islands, all foreign nationals, nected by air to Europe, only country in the Reading the title situated between Saudi except for citizens the US, Asia, Africa and Middle East to host a of this book, one Arabia’s east coast and of other Gulf Coopp other countries in the Formulap1 Grand Prix. might be forgiven When To Visit for asking the the Qatar peninsula. eration Council (GCC) Middle East. There is For those fascinated question: “Dil-- The 665 sq km kingdom The weather is at its countries. Visitors of also a 25pkm causeway by numbers, the first mun.... where is with a population of most pleasant between many Western countries link to Saudi Arabia. race was held on April that?” Dilmun is 700,000,��hrain welcomes November and March. can obtain visas on 4, 2004 (04p04p04); the ancient name more than 3 million June to September arrival at the airport. the next from April 1p3, for Bahrain, tourists each year. can be very hot. 2005 (01/02/03p04p05). a small island kingdom lapped by the aquama- rine waters of the Arabian Gulf. Its history dates back several thousand years. By Ali Hussain Mushaima Archaeological digs continue to reveal many clues, but this much is already known: Dilmun h h hh h h hh h h hh ig h hhh hh h hhhhhhhhhh hhh hhhhhh hhhhhh h hh h h h h hh hInternational had an advanced civilisation, with a Circuit (BIC) on June 22, 2004, from the Sakhir desert area. -

The Best of Times? Petroleum Politics in Canada

The Best of Times? Petroleum Politics in Canada Annual Meeting of the Canadian Political Science Assoication Draft Only – Not for Quotation Halifax, May 2003 Keith Brownsey Mount Royal College Calgary, Alberta 1. Introduction: It is the best of times for the Canadian oil and gas industry. As natural gas and oil prices have risen over the past two years petroleum companies have seen their profits increase dramatically.1 Domestic exploration is at unprecedented levels and investment in convention oil and gas production is increasing. It is also the worst of times for Canada’s oil and gas industry. Uncertainty, competition, and costs have created a situation of mounting uncertainty. Prices for oil and gas remain unstable, foreign investments are subject to increasing domestic and international scrutiny, aboriginal land claims threaten to disrupt domestic exploration and production, and the Kyoto Protocol to the United nations Framework Concention on Climate Change2 posses extra costs in an increasingly competitive world market for oil. Reserves in the Atlantic Offshore, moreover, have proven to be more elusive while conventional supplies of oil and natural gas are in decline and the massive reserves of the oil sands and heavy oil in western Canada have proven to be far more expensive to recover than oil from the middle east. The present may be profitable but the future holds little promise. The political-economic situation of uncertainty is framed within the context of competing ideologies and policies of the federal and producing provinces. The most contentious issue within the Canadian oil and gas industry is the Kyoto Protocol To The United Nations Framework Convention On Climate Change. -

M-Real Is Paperboa Supplier. M Innovative and Pape Commun End

Annual Report Annual Report Report Annual M-real is Europe’s leading primary fibre 2009 paperboard producer and a major paper supplier. M-real offers its customers innovative high-performance paperboards and papers for consumer packaging, communications and advertising end-uses. Annual Report Annual Report Report Annual M-real is Europe’s leading primary fibre 2009 paperboard producer and a major paper supplier. M-real offers its customers innovative high-performance paperboards and papers for consumer packaging, communications and advertising end-uses. KEY FIGURES AND page 2 M-real YEAR 2009 IN BRIEF 4 Year 2009 in brief 6 Key figures 8 CEO’s review Consumer02 Packaging 12 Office Papers 14 Speciality Papers 16 Market Pulp and Energy 18 page BUSINESS Operating environment 20 Raw materials 22 Managing environmental impacts 24 Energy and climate 26 Personnel 2810 FINANCIAL REPORT 2009 page 32 Report of the Board of Directors 2009 40 Consolidated financial statements 99 Parent company’s fnancial statements 30110 Corporate Governance Statement 118 Board of directors 120 Management team 128 Financial reporting 130 Contact details From forest to end user Raw materials Production Products M-real is committed to using wood raw M-real uses the best available techno- M-real’s production processes are based material from sustainably managed forests logy in its production units. The key on the economic use of resources and on in compliance with local legislation. The principles of production include conti- minimising the environmental impact of role of certified quality and environmental nuous improvement of operations and the products throughout their life cycle. -

Appendix I Chronology of Events

Appendix I Chronology of Events 1908: Oil is discovered in Persia by a syndicate of the Burmah Oil Company, the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC) 1911: United States Supreme Court orders the dissolution of Standard Oil Trust 1914: The British government purchases a majority holding in APOC 1914-18: World War I and the mechanisation of the battlefield 1920-23: The British government considers selling its holding in APOC 1922-28: Negotiation of the 'Red Line' and the 'As-Is' agreements 1932-33: Shah Reza Pahlavi cancels Anglo-Iranian Oil Company's (AIOC) con cession; AIOC wins it back 1934: AIOC and Gulf gain joint concession in Kuwait 1938: Mexico nationalises its oil companies 1939-45: World War II 1950: Fifty-fifty (participation) agreement between Aramco and Saudi Arabia 1950: Mohammed Mossadegh nationalises AIOC assets in Iran 1951-53: Korean War 1953: Mossadegh is overthrown and the Shah returns to power. The manage ment of Iraqi oil operations is contracted to an international consortium and AIOC obtains a 40 per cent majority stake Reports surface that the Conservative government is to dispose of its 56 per cent holding in AIOC 1956: Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt announces the appropriation of the Suez canal 1957: European Economic Community established 1960: Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries founded in Baghdad 1964: First round licences are awarded for exploration in the North Sea by the Department of Trade and Industry 1965: British Petroleum (BP) discovers gas in the North Sea 1965: Britain imposes sanctions -

Linking China's Energy Strategy with Venezuela

Linking China’s Energy Strategy with Venezuela: Transnationalization of Chinese NOCs and Geopolitical Implication of China-Venezuela Relations Author: Changwei Tang (10866825) Supervisor: Dr. M. (Mehdi) Parvizi Amineh Second Reader: Prof. Dr. Kurt Radtke Date: 26th June 2015 Master Thesis Political Science: International Relations Research Project: Political Economy of Energy 1 Table of Content Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgement .................................................................................................................... 5 Maps of the Selected Countries .............................................................................................. 6 List of Figures and Tables ....................................................................................................... 8 List of Abbreviations ............................................................................................................... 9 Chapter 1. Research Design .................................................................................................. 10 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 12 1.2 Literature Review .................................................................................................................................... 12 1.2.1 Chinese Energy Security ...........................................................................................................