In the Age of Climate Change Matthew

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

66, 13 January 2014

sanity, humanity and science probably the world’s most read economics journal real-world economics review - Subscribers: 23,924 Subscribe here Blog ISSN 1755-9472 - A journal of the World Economics Association (WEA) 12,557 members, join here - Sister open-access journals: Economic Thought and World Economic Review - back issues at www.paecon.net recent issues: 65 64 63 62 61 60 59 58 57 56 Issue no. 66, 13 January 2014 In this issue: Secular stagnation and endogenous money 2 Steve Keen Micro versus Macro 12 Lars Pålsson Syll On facts and values: a critique of the fact value dichotomy 30 Joseph Noko Modern Money Theory and New Currency Theory: A comparative discussion 38 Joseph Huber Fama-Shiller, the Prize Committee and the “Efficient Markets Hypothesis” 58 Bernard Guerrien and Ozgur Gun How capitalists learned to stop worrying and love the crisis 65 Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan Two approaches to global competition: A historical review 74 M. Shahid Alam Dimensions of real-world competition – a critical realist perspective 80 Hubert Buch-Hansen Information economics as mainstream economics and the limits of reform 95 Jamie Morgan and Brendan Sheehan The ℵ capability matrix: GDP and the economics of human development 109 Jorge Buzaglo Open access vs. academic power 127 C P Chandrasekhar Interview with Edward Fullbrook on New Paradigm Economics vs. Old Paradigm Economics 131 Book review of The Great Eurozone Disaster: From Crisis to Global New Deal by Heikki Patomäki 144 Comment: Romar Correa on “A Copernican Turn in Banking Union”, by Thomas Mayer 147 Board of Editors, past contributors, submissions and etc. -

Capitalism As a Mode of Power. Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan Interviewed by Piotr Dutkiewicz

Capitalism as a Mode of Power Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan Interviewed by Piotr Dutkiewicz Jerusalem, Montreal and Ottawa, July 2013 www.bnarchives.net Creative Commons A shorter version of this interview is forthcoming in 22 Ideas to Fix the World: Conver- sations with the World’s Foremost Thinkers, edited by Piotr Dutkiewicz and Richard Sakwa (New York: New York University Press, WPF and the Social Science Re- search Council, 2013). Piotr Dutkiewicz: In a unique two-pronged dovetailing discussion, frequent collabo- rators and coauthors Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler discuss the nature of contemporary capitalism. Their central argument is that the dominant approaches to studying the market – liberalism and Marxism – are as flawed as the market itself. Offering a historically rich and analytically incisive critique of the recent history of capitalism and crisis, they suggest that instead of studying the relations of capital to power we must conceptualize capital as power if we are to understand the dynamics of the market system. This approach allows us to examine the seemingly paradoxical workings of the capitalist mechanism, whereby profit and capitalization are divorced from productivity and machines in the so-called real economy. Indeed Nitzan and Bichler paint a picture of a strained system whose component parts exist in an an- tagonistic relationship. In their opinion, the current crisis is a systemic one afflicting a fatally flawed system. However, it is not one that seems to be giving birth to a uni- fied opposition movement or to a new mode of thinking. The two political econo- mists call for nothing short of a new mode of imagining the market, our political sys- tem, and our very world. -

Rising Corporate Concentration, Declining Trade Union Power, and the Growing Income Gap: American Prosperity in Historical Perspective Jordan Brennan

Rising Corporate Concentration, Declining Trade Union Power, and the Growing Income Gap: American Prosperity in Historical Perspective Jordan Brennan February 2016 Rising Corporate Concentration, Declining Trade Union Power, and the Growing Income Gap: American Prosperity in Historical Perspective Jordan Brennan* March 2016 *Jordan Brennan is an economist with Unifor, Canada’s largest private sector labor union, and a research associate of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. E-mail: [email protected]. Website: www.jordanbrennan.org. Contents Executive Summary 2 Acknowledgments 4 List of Figures 5 Part I: Corporate Concentration, Secular Stagnation, and the Growing Income Gap 6 Part II: Labor Unions, Inflation, and the Making of an Inclusive Prosperity 24 Appendix 48 References 51 1 Executive Summary The rise of income inequality amidst the deceleration of GDP growth must rank as two of the most perplexing and challenging problems in contemporary American capitalism. Comparing 1935–80 with 1980–2013—that is, the Keynesian-inspired welfare regime and, later, neoliberal globalization—the average annual rate of GDP growth was more than halved and income inequality went from a postwar low in 1976 to a postwar high in 2012. How do we account for this double-sided phenomenon? The conventional explanations of secular stagnation and elevated inequality are inadequate, largely because mainstream (“neoclassical”) economics rejects the notion that the amassment and exercise of institutional power play a role in the normal functioning of markets and business. This analytical inadequacy has left important causal elements outside the purview of researchers, policymakers, and the public at large. This two-part analysis investigates some of the causes and consequences of income inequality and secular stagnation in the United States. -

The Buy-To-Build Indicator New Estimates and Comment

The Buy-to-Build Indicator New Estimates and Comment Joseph Francis, Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan1 London, Jerusalem and Montreal March-April 2013 Creative Commons The first part of the exchange is a short article by Joseph Francis. The article provides new estimates and an assessment of the buy-to-build indicator for the United States and Britain. The second part offers commentary by Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan. 1 Joseph Francis is a PhD candidate at the London School of Economics ([email protected]; http://www.joefrancis.info/). Shimshon Bichler teaches political economy at colleges and universities in Israel ([email protected]; http://bnarchives.net). Jonathan Nitzan teaches political economy at York University in Toronto ([email protected]; http://bnarchives.net). The Buy-to-Build Indicator: New Estimates for Britain and the United States Joseph Francis* London School of Economics www.joefrancis.info March 2013 This note presents new long-term estimates of what Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler (2002: 53-4, 82-3; 2009: Ch.15) have named the ‘buy-to-build indicator’, which is calculated as the value of mergers and acquisitions as a percentage of gross capital form- ation. Estimating the buy-to-build indicators is not simple, principally due to the absence of consistent series for expenditure on mergers and acquisitions. Nevertheless, as this note describes, it has proven possible to calculate them for both Britain and the United States. For Britain, the new estimates build principally on the research of the Leslie Hannah, as well as official government statistics, while for the United States, they repres- ent significant revisions of Nitzan and Bichler’s own original estimates. -

Academic Labour, Digital Media and Capitalism

Academic Labour, Digital Media and Capitalism Special Issue, edited by Thomas Allmer and Ergin Bulut tripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique 16 (1), 2018, pp. 44-240 http://www.triple-c.at Academic Labour, Digital Media and Capitalism Special Issue, edited by Thomas Allmer and Ergin Bulut tripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique 16 (1), 2018, pp. 44-240 Table of Contents Thomas Allmer and Ergin Bulut: Introduction: Academic Labour, Digital Media and Capitalism, pp. 44-48 Thomas Allmer: Theorising and Analysing Academic Labour, pp. 49-77 Maxime Ouellet and Éric Martin: University Transformations and the New Knowledge Production Regime in Informational Capitalism, pp. 78-96 Richard Hall: On the Alienation of Academic Labour and the Possibilities for Mass Intellectuality, pp. 97-113 Marco Briziarelli and Joseph L. Flores: Professing Contradictions: Knowledge Work and the Neoliberal Condition of Academic Workers, pp. 114-128 Jamie Woodcock: Digital Labour in the University: Understanding the Transformations of Academic Work in the UK, pp. 129-142 Jan Fernback: Academic/Digital Work: ICTs, Knowledge Capital, and the Question of Educational Quality, pp. 143-158 Christophe Magis: Manual Labour, Intellectual Labour and Digital (Academic) Labour. The Practice/Theory Debate in the Digital Humanities, pp. 159-175 Karen Gregory and sava saheli singh: Anger in Academic Twitter: Sharing, Caring, and Getting Mad Online, pp. 176-193 Andreas Wittel: Higher Education as a Gift and as a Commons, pp. 194-213 Zeena Feldman and Marisol Sandoval: Metric Power and the Academic Self: Neoliberalism, Knowledge and Resistance in the British University, pp. 214-233 Güven Bakırezer, Derya Keskin Demirer and Adem Yeşilyurt: In Pursuit of an Alternative Academy: The Case of Kocaeli Academy for Solidarity (Non-Peer-Reviewed Reflection Article), pp. -

A Casp Model of the Stock Market Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan1

A CasP Model of the Stock Market Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan1 Jerusalem and Montreal, November 2016 bnarchives.net / Creative Commons Abstract Most explanations of stock market booms and busts are based on contrasting the underlying ‘fundamental’ logic of the economy with the exogenous, non-economic factors that presumably distort it. Our paper offers a radically different model, examining the stock market not from the mechanical viewpoint of a distorted economy, but from the dialectical perspective of capital- ized power. The model demonstrates that (1) the valuation of equities represents capitalized power; (2) capitalized power is dialectically intertwined with systemic fear; and (3) systemic fear and capitalized power are mediated through strategic sabotage. This triangular model, we posit, can offer a basis for examining the asymptotes, or limits, of capitalized power and the ways in which these asymptotes relate to the historical and ongoing transformation of the cap- italist mode of power. 1. Introduction The purpose of this paper is to outline a capital-as-power, or CasP, model of the stock market. There are two reasons why such a model is needed: first, the stock market has become the main compass of the capitalist mode of power; and, second, so far, we have not developed a CasP theory to describe it.2 Surprising as it may sound, all long-term modeling of the stock market derives from a single meta-dogma that we have previously dubbed the ‘mismatch thesis’ (Bichler and Nitzan 2009, 2015a). The basic premise of this dogma is the general bifurcation between economics and politics (a shorthand for all non-economic realms of society) and the further division, within economics, between the so-called ‘real’ and ‘nominal’ spheres. -

Casp's 'Differential Accumulation Versus Veblen's '

WORKING PAPERS ON CAPITAL AS POWER No. 2018/08 CasP’s ‘Differential Accumulation versus Veblen’s ‘Differential Advantage’ Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan November 2018 http://www.capitalaspower.com/?p=2557 CasP’s ‘Differential Accumulation’ versus Veblen’s ‘Differential Advantage’ Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan1 Jerusalem and Montreal November 2018 bnarchives.net / Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) 1. Introduction This paper clarifies a common misrepresentation of our theory of capital as power, or CasP. Many observers tend to box CasP as an ‘institutionalist’ theory, tracing its central process of ‘differential ac- cumulation’ to Thorstein Veblen’s notion of ‘differential advantage’ (Cf. 1904, 1923). This view, we argue, betrays a misunderstanding of CasP, Veblen or both. As we show below, CasP’s notion of dif- ferential accumulation is not only different from, but also diametrically opposed to Veblen’s differential advantage. Our argument is articulated in several steps. Section 2 outlines the key claims of CasP, contrasting them with those of received theory and articulating the way in which they relate and lead to our concept of differential accumulation. Sections 3 and 4 examine Veblen’s twin concepts of strategic sabotage and differential advantage, showing that the latter is concerned not with differential profit, but with the earning of profit as such. Section 5 develops this claim further, demonstrating that Veblen’s analysis of accumulation, hostage to neoclassical absolutes, understood capitalists as seeking not differential profit, but maximum profit. Section 6 examines the historical context in which Veblen was writing, suggesting that this backdrop made it practically impossible for him to conceive – let alone theorize and measure – differential accumulation, even if he had wanted to. -

To Download The

$10 OFF $10 OFF WELLNESS MEMBERSHIP MICROCHIP New Clients Only All locations Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. Expires 3/31/2020 Expires 3/31/2020 Free First Office Exams FREE EXAM Extended Hours Complete Physical Exam Included New Clients Only Multiple Locations Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. 4 x 2” ad www.forevervets.com Expires 3/31/2020 Your Community Voice for 50 Years PONTEYour Community Voice VED for 50 YearsRA RRecorecorPONTE VEDRA dderer entertainment EEXXTRATRA! ! Featuring TV listings, streaming information, sports schedules, puzzles and more! July 2 - 8, 2020 has a new home at INSIDE: Phil Keoghan THE LINKS! The latest 1361 S. 13th Ave., Ste. 140 hosts “Tough as house and Jacksonville Beach homes listings Nails,” premiering Page 21 Wednesday on CBS. Offering: · Hydrafacials Getting ‘Tough’- · RF Microneedling · Body Contouring Phil Keoghan hosts and · B12 Complex / produces new CBS series Lipolean Injections Get Skinny with it! (904) 999-0977 1 x 5” ad www.SkinnyJax.com Kathleen Floryan PONTE VEDRA IS A HOT MARKET! REALTOR® Broker Associate BUYER CLOSED THIS IN 5 DAYS! 315 Park Forest Dr. Ponte Vedra, Fl 32081 Price $720,000 Beds 4/Bath 3 Built 2020 Sq Ft. 3,291 904-687-5146 [email protected] Call me to help www.kathleenfloryan.com you buy or sell. 4 x 3” ad BY JAY BOBBIN Phil Keoghan gives CBS a T competition What’s Available NOW On When Phil Keoghan created “Tough as Nails,” he didn’t foresee it being even more apt by the time it aired. -

Petroleum Politics: China and Its National Oil Companies

MASTER IN ADVANCED EUROPEAN AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES ANGLOPHONE BRANCH - Academic year 2012/2013 Master Thesis Petroleum Politics: China and Its National Oil Companies By Ellennor Grace M. FRANCISCO 26 June 2013 Supervised by: Dr. Laurent BAECHLER Deputy Director MAEIS To Whom I owe my willing and my running CONTENTS List of Tables and Figures v List of Abbreviations vi Chapter 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Literature Review 2 1.2 Methodologies 4 1.3 Objectives and Scope 4 Chapter 2. Historical Evolution of Chinese National Oil Companies 6 2.1 The Central Government and “Self-Reliance” (1950- 1977) 6 2.2 Breakdown and Corporatization: First Reform (1978- 1991) 7 2.3 Decentralization: Second Reform (1992- 2003) 11 2.4 Government Institutions and NOCs: A Move to Recentralization? (2003- 2010) 13 2.5 Corporate Governance, Ownership and Marketization 15 2.5.1 International Market 16 2.5.2 Domestic Market 17 Chapter 3. Chinese Politics and NOC Governance 19 3.1 CCP’s Controlling Mechanisms 19 3.1.1 State Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) 19 3.1.2 Central Organization Department 21 3.2 Transference Between Government and Corporate Positions 23 3.3 Traditional Connections and the Guanxi 26 3.4 Convergence of NOC Politics 29 Chapter 4. The “Big Four”: Overview of the Chinese Banking Sector 30 Preferential Treatment 33 Chapter 5. Oil Security and The Going Out Policy 36 5.1 The Policy Driver: Equity Oil 36 5.2 The Going Out Policy (zou chu qu) 37 5.2.1 The Development of OFDI and NOCs 37 5.2.2 Trends of Outward Foreign Investments 39 5.3 State Financing: The Chinese Policy Banks 42 5.4 Loans for Oil 44 Chapter 6. -

The Politics of Oil, Gas Contract Negotiations in Sub-Saharan Africa

The politics of oil, gas contract negotiations in Sub-Saharan Africa This article is part of DIIS Report 2014:25 “Policies and finance for economic development and trade” Read more at www.diis.dk THE POLITICS OF OIL, GAS CONTRACT NEGOTIATIONS IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA By: Rasmus Hundsbæk Pedersen, DIIS, 2014 SUMMARY Much attention has been paid to the management of revenues from petroleum resources in Sub-Saharan Africa. An entire body of literature on the resource curse has developed which points to corruption during the negotiation of contracts, as well as the mismanagement of revenues on the continent. The analyses provide the basis for policy advice for countries as well as donors; transparency and anti- corruption initiatives aimed at lifting the curse flourish. Though this paper is sympathetic to these initiatives, it argues that the analysis may underestimate the inherently political nature of the negotiation of contracts. Based on a review of the existing literature on contract negotiations in Africa, combined with a case study of Tanzania, the paper argues that the resource curse need not hit all countries on the African continent. By focusing on changes in the relative bargaining strength of actors involved in negotiating processes, it points to the choices and trade-offs that invariably affect the terms and conditions of exploration and production activities. Whereas international oil companies are often depicted as being in the driving seat, the last decade’s high oil prices may have shifted power in governments’ favor. Though their influence has declined, donors may still want to influence oil and gas politics under these circumstances. -

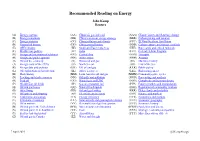

Recommended Reading on Energy

Recommended Reading on Energy John Kemp Reuters (A) Energy systems (AA) China oil, gas and coal (AAA) Climate issues and planetary change (B) Energy transitions (BB) China’s overseas energy strategy (BBB) Carbon pricing and taxation (C) Energy statistics (CC) China pollution and climate (CCC) El Nino/Southern Oscillation (D) General oil history (DD) China general history (DDD) Carbon capture and storage, synfuels (E) OPEC history (EE) South and East China Seas (EEE) Rare earths and critical minerals (F) Middle East politics (FF) India (FFF) Federal Helium Program (G) Energy and international relations (GG) Central Asia (GGG) Transport (H) Energy and public opinion (HH) Arctic issues (HHH) Aviation (I) Oil and the economy (II) Russia oil and gas (III) Maritime history (J) Energy crisis of the 1970s (JJ) North Sea oil (JJJ) Law of the Sea (K) Energy data and analysis (KK) UK oil and gas (KKK) Public policy (L) Oil exploration and production (LL) Africa resources (LLL) Risk management (M) Shale history (MM) Latin America oil and gas (MMM) Commodity price cycles (N) Fracking and shale resources (NN) Oil spills and pollution (NNN) Forecasting and analysis (O) Peak oil (OO) Natural gas and LNG (OOO) Complexity and systems theory (P) Middle East oil fields (PP) Gas as a transport fuel (PPP) Futures markets and manipulation (Q) Oil and gas leases (QQ) Natural Gas Liquids (QQQ) Regulation of commodity markets (R) Oil refining (RR) Oil and gas lending (RRR) Hedge funds and volatility (S) Oil tankers and shipping (SS) Electricity and security (SSS) Finance and markets (T) Tank farms and storage (TT) Energy efficiency (TTT) Economics and markets (U) Petroleum economics (UU) Solar activity and geomagnetic storms (UUU) Economic geography (V) Oil in wartime (VV) Renewables and grid integration (VVV) Economic history (W) Oil and gas in the United States (WW) Nuclear power and weapons (WWW) Epidemics and disease (X) Oil and gas in U.S. -

Introduction Continuity and Change in Venezuela’S Petro-Diplomacy

Introduction Continuity and Change in Venezuela’s Petro-Diplomacy Ralph S. Clem and Anthony P. Maingot Over the last decade, Venezuela has exerted an influence on the Western Hemisphere and indeed, global international relations, well beyond what one might expect from a country of 26.5 million people. In considering the reasons for this influence, one must of course take into account the country’s vast petroleum deposits. The wealth these generate, used traditionally to fi- nance national priorities, more recently has been heavily deployed to bolster Venezuela’s ambitious “Bolivarian”proof foreign policy. As with any country whose national income depends so heavily on export earnings from a single natural resource, Venezuela’s economic fate rests on its capacity to exploit that resource and, perhaps even more so, on the price set by the international market. The Venezuelan author Fernando Coronil calls this condition the “neo-colonial disease.” Without oil, there would be no Chávez, and certainly no “socialism of the twenty-first century.”1 Unpredict- ability is the signal character of the Venezuelan economy, and, consequently, no domestic or foreign policy assessments can be completely time-based. Nothing exemplifies this volatility better than the price of a barrel of oil, which was $148 when we began planning this collection of essays in mid- 2007, but which fell to less than $50, then climbed back to $70 by mid-2009. Instead of using a time-based approach, therefore, the essays in this volume attempt to trace the deep-rooted and enduring orientations of Venezuelan political culture and their influence on foreign policy, with special attention to the historical role petroleum has played in these considerations.