Democratic Republic of the Congo 2019 Mapping Trends in Government Internet Controls, 1999-2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monusco and Drc Elections

MONUSCO AND DRC ELECTIONS With current volatility over elections in Democratic Republic of the Congo, this paper provides background on the challenges and forewarns of MONUSCO’s inability to quell large scale electoral violence due to financial and logistical constraints. By Chandrima Das, Director of Peacekeeping Policy, UN Foundation. OVERVIEW The UN Peacekeeping Mission in the Dem- ment is asserting their authority and are ready to ocratic Republic of the Congo, known by the demonstrate their ability to hold credible elec- acronym “MONUSCO,” is critical to supporting tions. DRC President Joseph Kabila stated during peace and stability in the Democratic Republic the UN General Assembly high-level week in of the Congo (DRC). MONUSCO battles back September 2018: “I now reaffirm the irreversible militias, holds parties accountable to the peace nature of our decision to hold the elections as agreement, and works to ensure political stabil- planned at the end of this year. Everything will ity. Presidential elections were set to take place be done in order to ensure that these elections on December 23 of this year, after two years are peaceful and credible.” of delay. While they may be delayed further, MONUSCO has worked to train security ser- due to repressive tactics by the government, vices across the country to minimize excessive the potential for electoral violence and fraud is use of force during protests and demonstrations. high. In addition, due to MONUSCO’s capacity However, MONUSCO troops are spread thin restraints, the mission will not be able to protect across the entire country, with less than 1,000 civilians if large scale electoral violence occurs. -

Supply Annual Report 2019 Scaling up for Impact 2 UNICEF Supply Annual Report 2019 SCALING up for IMPACT 3

Supply Annual Report 2019 Scaling Up for Impact 2 UNICEF Supply Annual Report 2019 SCALING UP FOR IMPACT 3 Students smile at the camera in front of their school in the village of Tamroro, in the centre of Niger 4 UNICEF Supply Annual Report 2019 SCALING UP FOR IMPACT 5 Contents Foreword 7 SCALING UP FOR IMPACT Innovation at the heart of humanitarian response 10 From ships to schools: Finding construction solutions in local innovation 12 Warehouse in a pocket app scales up to improve supply chain efficiency 14 Scaling vaccine procurement in an evolving landscape of supply and demand 16 Strengthening domestic resources to deliver life-saving commodities 18 WORKING TOGETHER Keeping vaccines safe through the last mile of their journey 20 The UNICEF Supply Community behind our results 42 Improving nutrition supply chains for children 22 Supply Community testimonials 44 Strategic collaboration 46 Supply partnerships 48 RESPONDING TO EMERGENCIES UNICEF on the front lines 26 UNICEF supply response in the highest-level ACHIEVING RESULTS emergencies in 2019 28 Procurement overview 2019 52 Emergency overview highlights by country 30 Major commodity groups 54 Scaling up supply response Services 56 for global health emergencies 32 Country of supplier / Region of use 57 Juliette smiles on Responding with supplies the playground inside to Cyclones Idai and Kenneth 36 Savings overview 2019 58 Reaching new heights, a youth-friendly space in the Mahama Refugee Camp, home to thousands of Strategic prepositioning of supplies Burundian children, in South Sudan 38 ANNEXES such as herself for every child. Scaling up construction in Yemen 39 UNICEF global procurement statistics 60 6 UNICEF Supply Annual Report 2019 Foreword 7 Scaling up for impact In 2019, UNICEF annual procurement of goods and services for children reached a record $3.826 billion. -

Airbox 4G+ Quick Start Guide @

Airbox 4G+ Quick Start Guide @ 1 M FR Insérer la carte SIM EN Insert SIM card SIM ES Inserta la tarjeta SIM NL Plaats de simkaart PL Włóż kartę SIM RO Introduceți cartela SIM RU Вставьте SIM-карту http://airbox.home SK Vložte Sim Kartu AR أدخل بطاقة SIM 2 FR Allumer le dispositif EN Switch on the device ES Enciende el dispositivo NL Zet het apparaat aan PL Włącz urządzenie RO Porniţi dispozitivul RU Включите устройство SK Zapnite Airbox AR قم بتشغيل الجهاز Airbox-xxxx 3 Connection x1 ********* x Security Key : *********** FR Se connecter au réseau WiFi de l’Airbox EN Connect to Airbox WiFi network OK Cancel ES Conéctate al WiFi del Airbox Select Airbox NL Maak verbinding met het wifi-netwerk van de Airbox network PL Podłącz się do sieci WiFi Airbox Airbox-xxxx Airbox-xxxx Input password RO Conectaţi-vă la rețeaua WiFi Airbox Xxxxxxxxx RU *********** Подключите WiFi сеть Airbox Xxxxxxxxx SK Nadviažte spojenie s bezdrôtovou sieťou zariadenia Xxxxxxxxx AR إتصل بالشبكة الﻻسلكيه للـ Airbox Xxxxxxxxx Create your password Software update The administrator password allows you to modify the settings of your device. Your password should consist of Auto-update numbers, letters, or characters. Auto-update feature allows you to automatically get the latest version of the software and ensure Login admin the best experience with your device. Password I have read and agree to the updated Privacy Notice 4 5 Weak Medium Strong Confirm password Next Finish FR Lancer un navigateur web et aller sur http://airbox.home EN Create your administrator password -

DRC Digital Rights & Inclusion 2020 Report.Cdr

LONDA DRC DIGITAL RIGHTS AND INCLUSION A PARADIGM INITIATIVE PUBLICATION REPORT LONDA DRC DIGITAL RIGHTS AND INCLUSION REPORT A PARADIGM INITIATIVE PUBLICATION Published by Paradigm Initiative Borno Way, Yaba, Lagos, Nigeria Email: [email protected] www.paradigmhq.org Published in April Report written by Providence Baraka Editorial Team: ‘Gbenga Sesan, Kathleen Ndongmo, Koliwe Majama, Margaret Nyambura Ndung’u, Mawaki Chango, Nnenna Paul-Ugochukwu and Thobekile Matimbe. Design & Layout by Luce Concepts This publication may be reproduced for non-commercial use in any form provided due credit is given to the publishers, and the work is presented without any distortion. Copyright © Paradigm Initiative Creative Commons Attribution . International (CC BY .) CONTENTS INTRODUCTION LONDA INTERNET POLICIES DRC DIGITAL RIGHTS AND INCLUSION REPORT AND REGULATIONS A PARADIGM INITIATIVE PUBLICATION HUMAN RIGHTS AND DIGITAL EXCLUSION POSITIVE DEVELOPMENTS FOR THE PROMOTION OF INCLUSION AND HUMAN RIGHTS Civil society organizations continue to work to advance digital rights and inclusion in Africa, ensuring best practices are adopted into policy and legislation. This report analyses the state of digital rights and inclusion in DRC, examining CONCLUSION AND violations and gaps, investigating the use and application of RECOMMENDATIONS policy and legislation, highlighting milestones and proffering recommendations for the digital landscape in DRC. This edition captures among other issues, the digital divide worsened by the COVID- pandemic and unearths infractions on different thematic areas such as privacy, access to information, and freedom of expression with the legislative and policy background well enunciated. @ParadigmHQ DRC DIGITAL RIGHTS AND INCLUSION 2020 REPORT The Democratic Republic of Congo is the largest country in Central Africa with over 88 million inhabitants, making it the fourth most populous country in Africa behind Nigeria, Ethiopia and Egypt. -

Democratic Re Public of the Congo

Democratic Re public of the Congo 1 Introduction The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is the second-largest country in Africa, with a population of approximately 84 million people.1 The DRC gained independence from Belgium in 1960. Its post-independence history is bloody: the first post-independence leader, Patrice Lumumba, was assassinated in 1961. In 1965, military officer Mobutu Sese Seko assumed power after a period of civil war. Mobutu ruled his one-party state (which he renamed Zaire) until 1996, when he was ousted by an armed coalition led by Laurent Kabila. However, the coun- try remained dangerously unstable and effectively in a state of civil war. In 2001, Laurent Kabila was assassinated by his bodyguard and was succeeded by his son, Joseph Kabila. Although Joseph Kabila is credited with introducing a number of important reforms, most notably a new constitution, his democratic credentials remained extremely poor. The last election which he won (in 2011) is disputed and lacked credibility due to widespread irregularities. President Kabila’s sec- ond five-year term of office ended in December 2016, but the DRC failed to hold elections and he ruled without an electoral mandate, albeit with the backing of the Constitutional Court. In May 2016, the Constitutional Court, in a heavily crit- icised judgment, interpreted section 70 of the constitution, which provides that the president continues in office until the assumption of office of his successor, as entitling President Kabila to remain in office without an election having taken place. Critics argue that the Constitutional Court should have found section 75 of the constitution applicable — this provides for the Head of the Senate to assume office temporarily in the case of a presidential vacancy.2 In August 2018, President Kabila announced he would not be running for a third term and the ruling party chose Emmanuel Shadari, seen as a Kabila loyalist,3 as its candidate for the presidential elections. -

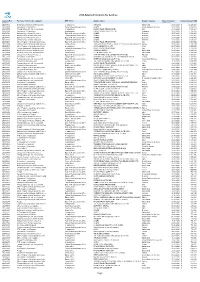

2020 Awarded Contracts for Services Page 1

2020 Awarded Contracts for Services Contract Ref. Purchase Order for the supply of WHO Office Supplier Name Supplier Country Date of Contract Contract Amount USD Number Approval 202511512 Building Construction incl Renovation Headquarters IMPLENIA Switzerland 20.02.2020$ 25,225,723 202563898 Renovation / Construction Eastern Mediterranean Office UNOPS United States of America 10.07.2020$ 9,000,000 202587575 Transportation (air, rail, sea, ground) Headquarters WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME Italy 21.09.2020$ 7,468,267 202576069 Renovation / Construction Headquarters CADG ENGINEERING PTE. LTD. Singapore 14.09.2020$ 7,135,155 202561741 Outsourcing of Human Resources Eastern Mediterranean Office UNOPS Denmark 05.07.2020$ 5,654,852 202586965 Outsourcing of Human Resources Eastern Mediterranean Office UNOPS Denmark 18.09.2020$ 5,654,852 202484781 Outsourcing of Human Resources Eastern Mediterranean Office UNOPS Denmark 21.01.2020$ 5,649,432 202538768 Outsourcing of Human Resources Eastern Mediterranean Office UNOPS Denmark 17.04.2020$ 5,649,432 202541083 Other Program related Operating Costs Eastern Mediterranean Office WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME Italy 27.04.2020$ 5,207,950 202571690 Outsourcing Consulting & Audit Services Europe Office DOCTORS WORLDWIDE – TURKEY “YERYUZU DOKTORLARI DERNEGI”Turkey 03.08.2020$ 4,594,479 202562137 Other Program related Operating Costs Headquarters CHINA MEHECO CO., LTD. China 06.07.2020$ 4,200,000 202596308 Custom clearance & Warehouse rental Eastern Mediterranean Office WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME Italy 14.10.2020$ 4,010,189 202523184 Building Construction incl Renovation Headquarters APLEONA HSG SA Switzerland 06.03.2020$ 4,004,128 202532908 Building Construction incl Renovation Headquarters ITTEN+BRECHBUHL SA Switzerland 27.03.2020$ 3,960,989 202484795 Outsourcing of Human Resources Eastern Mediterranean Office CHIP TRAINING AND CONSULTING (PVT) LTD. -

Republique Democratique Du Congo Ministere Des

REPUBLIQUE DEMOCRATIQUE DU CONGO MINISTERE DES FINANCES DIRECTION GENERALE DES IMPÔTS DIRECTION DE L'ASSIETTE FISCALE REPERTOIRE DES CONTRIBUABLES ASSUJETTIS A LA TVA, ARRETE AU 28 FEVRIER 2019 FORME SIEGE OU ANCIEN SERVICE NOUVEAU SERVICE N NIF NOMS OU RAISON SOCIALE SIGLE ADRESSE SECTEUR DACTIVITE ETAT SOCIETE JURIDIQUE SUCCURSALE GESTIONNAIRE GESTIONNAIRE Commerce Général et 1 A1200188T PM 3 G SERVICES SPRL SIEGE SOCIAL Q/MAINDOMBE N°35/C MATETE Import-Export EN ACTIVITE CDI / KINSHASA CDI / KINSHASA AV. NZOBE N°128 Q/BISENGO Commerce Général et 2 A1300881Y PM 3 rd YES SPRL SIEGE SOCIAL C/BANDALUNGWA Import-Export EN ACTIVITE CDI / KINSHASA CDI / KINSHASA Prestation de services 3 A1610526K PM 360° COMMUNICATIONS SARL SIEGE SOCIAL AV. DE LA JUSTICE N°44 C/GOMBE et travaux immobiliers EN ACTIVITE CDI / KINSHASA CDI / KINSHASA Commerce Général et 4 A1505996K PM 3MC SARL SIEGE SOCIAL AV.DEAV. LUKUSA LA VALLEE N°2 Q/GOLF N°4B APP. C/GOMBE RESIDENCE Import-Export EN ACTIVITE CDI / KINSHASA CDI / KINSHASA PRESTIGE C/GOMBE D/LUKUNGA Prestation de services 5 A1419266H PM 4CIT SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS LIMITED SIEGE SOCIAL V/KINSHASA et travaux immobiliers EN ACTIVITE CDI / KINSHASA CDI / KINSHASA 4K PYRAMIDE DE CONSTRUCTIONS ET Prestation de services 6 A1515786B PM TRAVAUX SARL SIEGE SOCIAL AV. KABAYIDI N°68 Q/NDANU C/LIMETE Télécom.et travaux et immobiliers nouvelles EN ACTIVITE CDI / KINSHASA CDI / KINSHASA AV.BAKONGO N°644 C/GOMBE technologies 7 A1408818B PM 7 SUR 7.CD SIEGE SOCIAL D/LUKUNGA V/KINSHASA d'information EN ACTIVITE CDI / KINSHASA CDI / KINSHASA Commerce Général et 8 A1515519L PM A CASA MIA SARL SIEGE SOCIAL AV. -

Democratic Republic of Congo: Background and U.S. Relations

Democratic Republic of Congo: Background and U.S. Relations Updated April 30, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R43166 Democratic Republic of Congo: Background and U.S. Relations Summary The United States and other donors have focused substantial resources on stabilizing the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) since the early 2000s, when “Africa’s World War”—a conflict that drew in multiple neighboring countries and reportedly caused millions of deaths— drew to a close. DRC hosts the world’s largest U.N. peacekeeping operation and is a major recipient of donor aid. Conflict has nonetheless persisted in eastern DRC, prolonging instability and an enduring humanitarian crisis in Africa’s Great Lakes region. New unrest erupted as elections were repeatedly delayed past 2016, their scheduled date, leaving widely unpopular President Joseph Kabila in office. Security forces brutally cracked down on protests, while new conflicts emerged in previously stable regions, possibly fueled by political interference. An ongoing Ebola outbreak in the east has added to DRC’s challenges. In April 2019, the Islamic State organization claimed responsibility for an attack on local soldiers in the Ebola-affected area, an apparent effort to rebrand a local armed group known as the Allied Democratic Forces. National elections were ultimately held on December 30, 2018, following intense domestic and regional pressure. Opposition figure Felix Tshisekedi unexpectedly won the presidential contest, though his ability to assert a popular mandate may be undermined by allegations that the official results were rigged to deny victory to a more hardline opposition rival. Many Congolese nonetheless reacted to the outcome with relief and/or enthusiasm, noting that Kabila would step down and that voters had soundly defeated his stated choice of successor, a former Interior Minister. -

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Democratic Republic of the Congo: Five priorities for a State that respects human rights March 2019 / N° 732a March Cover picture : Supporters of the runner up in the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s presidential elections, Martin Fayulu, sing and dance ahead of a rally against the presidential results on February 2, 2019 in Kinshasa.». © John Wessels/AFP Summary Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Priority 1: Fighting against impunity, promoting truth and strengthening justice in order to guarantee national reconciliation and lasting peace ........................................................................................................ 6 Priority 2 : Respect fundamental rights and promote political dialogue ............................................................. 11 Priority 3 : Build an egalitarian society by promoting the rights of women and gender equality .......................... 13 Priority 4 : Enact substantial reforms to build the rule of law and democracy .................................................... 15 Priority 5 : Strengthen cooperation with the international community and mechanisms for the protection of human rights ...................................................................................................................................... 19 Introduction On 20 January 2019, the Constitutional Court confirmed the election of Felix Tshisekedi as President of the Democratic Republic -

Most Socially Active Professionals

Africa’s Most Socially Active Telecommunications Professionals – October 2020 Position Company Name LinkedIN URL Location Size No. Employees on LinkedIn No. Employees Shared (Last 30 Days) % Shared (Last 30 Days) 1 Safaricom PLC https://www.linkedin.com/company/165812 Kenya 5001-10000 8,077 1,135 14.05% 2 UX Centers https://www.linkedin.com/company/34940342 Morocco 1001-5000 349 39 11.17% 3 ntel https://www.linkedin.com/company/10175549 Nigeria 1001-5000 343 34 9.91% 4 ZAP a minha TV https://www.linkedin.com/company/3113649 Angola 501-1000 442 43 9.73% 5 Econet Telecom Lesotho https://www.linkedin.com/company/415270 Lesotho 201-500 449 42 9.35% 6 Orange Mali https://www.linkedin.com/company/3165553 Mali 501-1000 641 59 9.20% 7 Adrian Kenya https://www.linkedin.com/company/5003340 Kenya 201-500 241 21 8.71% 8 MTN Business https://www.linkedin.com/company/597450 South Africa 501-1000 325 28 8.62% 9 MTN Cote d'Ivoire https://www.linkedin.com/company/220006 Côte d'Ivoire 501-1000 1,150 89 7.74% 10 Lonestar Cell/MTN Liberia https://www.linkedin.com/company/505129 Liberia 201-500 258 17 6.59% 11 9mobile https://www.linkedin.com/company/11210379 Nigeria 1001-5000 1,347 88 6.53% 12 National Telecommunications Regulatoryhttps://www.linkedin.com/company/33875 Authority (NTRA) of Egypt Egypt 201-500 341 22 6.45% 13 BISWAL LIMITED https://www.linkedin.com/company/8513474 Nigeria 501-1000 444 28 6.31% 14 Liquid Telecom South Africa https://www.linkedin.com/company/20586 South Africa 1001-5000 1,081 68 6.29% 15 Etisalat Misr https://www.linkedin.com/company/777868 -

1 Country Fact Sheet Democratic Republic Of

COUNTRY FACT SHEET DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO (October 2013) Disclaimer IOM has carried out the gathering of information with great care. IOM provides information at its best knowledge and in all conscience. Nevertheless, IOM cannot assume to be held accountable for the correctness of the information provided. Furthermore, IOM shall not be liable for any conclusions made or any results, which are drawn from the information provided by IOM. 1 Table of Contents I. GENERAL INFORMATION 3 II. HOUSING 10 III. HEALTH AND MEDICAL CARE 11 IV. ECONOMY AND SOCIAL SECURITY 14 V. EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM 22 VI. GENDER ISSUES 23 VII. INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS AND NGO’s 23 2 I. GENERAL INFORMATION General overview 1 Established as a Belgian colony in 1908, the Republic of the Congo gained its independence in 1960, but its early years were marred by political and social instability. Colonel Joseph Mobutu seized power and declared him self president in a November 1965 coup. He subsequently changed his name - to Mobutu Sese Seko - as well as that of the country - to Zaire. Mobutu retained his position for 32 years through several sham elections, as well as through the use of brutal force. Ethnic strife and civil war, touched off by a massive inflow of refugees in 1994 from fighting in Rwanda and Burundi, led in May 1997 to the toppling of the Mobutu regime by a rebellion backed by Rwanda and Uganda and fronted by Laurent Kabila. He renamed the country “the Democratic Republic of the Congo” (DRC), but in August 1998 his regime was itself challenged by a second insurrection again backed by Rwanda and Uganda. -

Waking the Sleeping Giant Development Pathways for the Democratic Republic of the Congo to 2050 Kouassi Yeboua, Jakkie Cilliers and Stellah Kwasi

30YEARS Waking the sleeping giant Development pathways for the Democratic Republic of the Congo to 2050 Kouassi Yeboua, Jakkie Cilliers and Stellah Kwasi Despite its abundant natural resources, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) ranks near the bottom in various human and economic development indicators and its average income is about 40% of its value at independence in 1960. Using the International Futures modelling platform, this report presents the DRC’s likely human and economic development prospects to 2050 on its current trajectory. Thereafter, the report models various complementary scenarios that explore the impact of sectoral improvements on the country’s future. CENTRAL AFRICA REPORT 18 | FEBRUARY 2021 Key points Bad governance, cronyism and corruption are supply, is impeding higher productivity holding back developmental progress. and growth. Despite its huge natural resources the Low completion rates and quality are some of Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) the challenges facing the education system. ranks near the bottom in various development There is a disconnect between this system and indicators and poverty is widespread. the needs of the labour market. The average income is about 40% of its value Congolese have little access to basic at independence in 1960. On the current healthcare, mainly due to lack of funding of the development trajectory, the projected income sector, mismanagement, shortage of qualified per capita by 2050 is almost the same as its medical staff and high cost of healthcare. value in the 1970s. The high fertility rate is constraining the Despite being the country with the largest prospects for human development.