Democratic Republic of Congo: Background and U.S. Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) Reports Children in Need of Humanitarian Assistance Its First COVID-19 Confirmed Case

ef Democratic Republic of the Congo Humanitarian Situation Report No. 03 © UNICEF/UN0231603/Herrmann Reporting Period: March 2020 Highlights Situation in Numbers 9,100,000 • 10 March, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) reports children in need of humanitarian assistance its first COVID-19 confirmed case. As of 31 March 2020, 109 confirmed cases have been recorded, of which 9 deaths and 3 (OCHA, HNO 2020) recovered patients have been reported. During the reporting period, the virus has affected the province of Kinshasa and North Kivu 15,600,000 people in need • In addition to UNICEF’s Humanitarian Action for Children (HAC) (OCHA, HNO 2020) 2020 appeal of $262 million, UNICEF’s COVID-19 response plan has a funding appeal of $58 million to support UNICEF’s response 5,010,000 in WASH/Infection Prevention and Control, risk communication, and community engagement. UNICEF’s response to COVID-19 Internally displaced people can be found on the following link (HNO 2020) 6,297 • During the reporting period, 26,789 in cholera-prone zones and cases of cholera reported other epidemic-affected areas benefiting from prevention and since January response WASH packages (Ministry of Health) UNICEF’s Response and Funding Status UNICEF Appeal 2020 9% US$ 262 million 11% 21% Funding Status (in US$) 15% Funds Carry- received forward, 10% $5.5 M $28.8M 10% 49% 21% 15% Funding gap, 3% $229.3M 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% 1 Funding Overview and Partnerships UNICEF appeals for US$ 262M to sustain the provision of humanitarian services for women and children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). -

Strengthening Routine Immunization in Haut-Lomami and Tanganyika Provinces

2020 EDITION ● 2019 YEAR IN REVIEW Strengthening routine immunization in Haut-Lomami and Tanganyika provinces Stepping up commitments for routine immunization commitment to mobilize provincial resources for Launched in 2018, the Democratic Republic of Congo’s vaccination in alignment with the Kinshasa Declaration. (DRC) ‘Mashako Plan’ aims to increase immunization This past year a vaccine-derived polio (cVDPV2) rates by 15% over 18 months to vaccinate an additional epidemic persisted in DRC due to low herd immunity, 220,000 children in nine vulnerable provinces. In with 85 cases recorded in the country—including 19 response, The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) cases in Haut-Lomami and 1 case in Tanganyika. This is providing direct financial support and technical underscores the importance of partners’ continued assistance through partners to address gaps in routine work toward strengthening immunization systems and immunization in two target provinces, Haut-Lomami advocating for sustainable routine immunization and Tanganyika. financing. Below is a review of the biggest highlights of 2019 was a banner year for immunization in the DRC. In 2019 in our continued fight against polio in DRC. July, the newly elected Congolese Head of State, Félix Antoine Tshisekedi Tshilombo, hosted the National Forum on Immunization and Polio Eradication. Bringing together governors, provincial assembly presidents, ministers of health, and technical experts from all 26 provinces, he declared his vision for improving immunization systems and achieving polio elimination in front of national and international attendees. The forum culminated in the signing of the Kinshasa Declaration committing national and provincial decision-makers to take specific action to provide oversight, accountability, and resources to immunization systems. -

Democratic Republic of the Congo INDIVIDUALS

CONSOLIDATED LIST OF FINANCIAL SANCTIONS TARGETS IN THE UK Last Updated:18/02/2021 Status: Asset Freeze Targets REGIME: Democratic Republic of the Congo INDIVIDUALS 1. Name 6: BADEGE 1: ERIC 2: n/a 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. DOB: --/--/1971. Nationality: Democratic Republic of the Congo Address: Rwanda (as of early 2016).Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):DRC0028 (UN Ref): CDi.001 (Further Identifiying Information):He fled to Rwanda in March 2013 and is still living there as of early 2016. INTERPOL-UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/notice/search/un/5272441 (Gender):Male Listed on: 23/01/2013 Last Updated: 20/01/2021 Group ID: 12838. 2. Name 6: BALUKU 1: SEKA 2: n/a 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. DOB: --/--/1977. a.k.a: (1) KAJAJU, Mzee (2) LUMONDE (3) LUMU (4) MUSA Nationality: Uganda Address: Kajuju camp of Medina II, Beni territory, North Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo (last known location).Position: Overall leader of the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) (CDe.001) Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):DRC0059 (UN Ref):CDi.036 (Further Identifiying Information):Longtime member of the ADF (CDe.001), Baluku used to be the second in command to ADF founder Jamil Mukulu (CDi.015) until he took over after FARDC military operation Sukola I in 2014. Listed on: 07/02/2020 Last Updated: 31/12/2020 Group ID: 13813. 3. Name 6: BOSHAB 1: EVARISTE 2: n/a 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. -

Vol. 85 Wednesday, No. 171 September 2, 2020 Pages 54481

Vol. 85 Wednesday, No. 171 September 2, 2020 Pages 54481–54884 OFFICE OF THE FEDERAL REGISTER VerDate Sep 11 2014 20:57 Sep 01, 2020 Jkt 250001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4710 Sfmt 4710 E:\FR\FM\02SEWS.LOC 02SEWS jbell on DSKJLSW7X2PROD with FR_WS II Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 171 / Wednesday, September 2, 2020 The FEDERAL REGISTER (ISSN 0097–6326) is published daily, SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES Monday through Friday, except official holidays, by the Office PUBLIC of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration, under the Federal Register Act (44 U.S.C. Ch. 15) Subscriptions: and the regulations of the Administrative Committee of the Federal Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Register (1 CFR Ch. I). The Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Assistance with public subscriptions 202–512–1806 Government Publishing Office, is the exclusive distributor of the official edition. Periodicals postage is paid at Washington, DC. General online information 202–512–1530; 1–888–293–6498 Single copies/back copies: The FEDERAL REGISTER provides a uniform system for making available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and Assistance with public single copies 1–866–512–1800 Executive Orders, Federal agency documents having general (Toll-Free) applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published FEDERAL AGENCIES by act of Congress, and other Federal agency documents of public Subscriptions: interest. Assistance with Federal agency subscriptions: Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Federal Register the day before they are published, unless the Email [email protected] issuing agency requests earlier filing. -

Of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO

Assessing the of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO REPORT 3/2019 Publisher: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs Copyright: © Norwegian Institute of International Affairs 2019 ISBN: 978-82-7002-346-2 Any views expressed in this publication are those of the author. Tey should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. Te text may not be re-published in part or in full without the permission of NUPI and the authors. Visiting address: C.J. Hambros plass 2d Address: P.O. Box 8159 Dep. NO-0033 Oslo, Norway Internet: effectivepeaceops.net | www.nupi.no E-mail: [email protected] Fax: [+ 47] 22 99 40 50 Tel: [+ 47] 22 99 40 00 Assessing the Efectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC (MONUC-MONUSCO) Lead Author Dr Alexandra Novosseloff, International Peace Institute (IPI), New York and Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Oslo Co-authors Dr Adriana Erthal Abdenur, Igarapé Institute, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Prof. Tomas Mandrup, Stellenbosch University, South Africa, and Royal Danish Defence College, Copenhagen Aaron Pangburn, Social Science Research Council (SSRC), New York Data Contributors Ryan Rappa and Paul von Chamier, Center on International Cooperation (CIC), New York University, New York EPON Series Editor Dr Cedric de Coning, NUPI External Reference Group Dr Tatiana Carayannis, SSRC, New York Lisa Sharland, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Canberra Dr Charles Hunt, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University, Australia Adam Day, Centre for Policy Research, UN University, New York Cover photo: UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti UN Photo/ Abel Kavanagh Contents Acknowledgements 5 Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 13 Te effectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC across eight critical dimensions 14 Strategic and Operational Impact of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Constraints and Challenges of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Current Dilemmas 19 Introduction 21 Section 1. -

Monusco and Drc Elections

MONUSCO AND DRC ELECTIONS With current volatility over elections in Democratic Republic of the Congo, this paper provides background on the challenges and forewarns of MONUSCO’s inability to quell large scale electoral violence due to financial and logistical constraints. By Chandrima Das, Director of Peacekeeping Policy, UN Foundation. OVERVIEW The UN Peacekeeping Mission in the Dem- ment is asserting their authority and are ready to ocratic Republic of the Congo, known by the demonstrate their ability to hold credible elec- acronym “MONUSCO,” is critical to supporting tions. DRC President Joseph Kabila stated during peace and stability in the Democratic Republic the UN General Assembly high-level week in of the Congo (DRC). MONUSCO battles back September 2018: “I now reaffirm the irreversible militias, holds parties accountable to the peace nature of our decision to hold the elections as agreement, and works to ensure political stabil- planned at the end of this year. Everything will ity. Presidential elections were set to take place be done in order to ensure that these elections on December 23 of this year, after two years are peaceful and credible.” of delay. While they may be delayed further, MONUSCO has worked to train security ser- due to repressive tactics by the government, vices across the country to minimize excessive the potential for electoral violence and fraud is use of force during protests and demonstrations. high. In addition, due to MONUSCO’s capacity However, MONUSCO troops are spread thin restraints, the mission will not be able to protect across the entire country, with less than 1,000 civilians if large scale electoral violence occurs. -

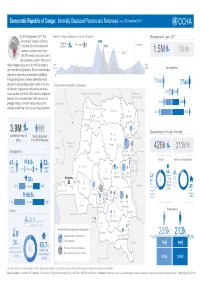

FINAL-Fact-Sheet-Infographic-19-Oct-2017 English Version.Ai

Democratic Republic of Congo: Internally Displaced Persons and Returnees (as of 30 September 2017) As of 30 September 2017, the Monthly trend of displacement in last 18 months Displacement in year 2017 Democratic Republic of Congo 432k Displaced Returnees 3rd Quarter recorded 3.9 million displaced persons 388k persons, including more than 2017 1.5M 1M 400,000 newly displaced ones in the prior three months. With over 1 million displaced persons, North Kivu remains April Sept. Demographics the most affected province. Recent months have 2016 2017 also seen large return movements, notably in 0 Tanganyika province, where authorities have 714k decided to vacate displacement sites in the city Displacement distribution by province 774k of Kalemie. In provinces affected by the Kasai 27k 29k crisis, as well, some 631,000 internally displaced CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC REPUBLIC OF persons have returned home, often to burnt or SOUTH SUDAN 263k 285k pillaged villages. Overall, armed attacks and CAMEROON clashes remain the main cause of displacement. North-Ubangi Bas-Uele 2 424k 460k Haut-Uele South-Ubangi Mongala 3.9M 45 Displacement in the last 3 months current number of Ituri 325 forcibly displaced DrDraff UGANDA 42 IDPs in the affected areas Equateur 24 REPUBLIC OF Tshopo CONGO GABON 428k 213k Demographics Tshuapa 1 024 267 North Kivu RWANDA Causes Nature of accomodation 48% 4.5% 52% Maï-Ndombe men >59 years women 71k 77k BURUNDI (1.9M) (2M) 21 % 254 45 545 104 55 Maniema South Kivu Clashes Kinshasa Sankuru and % % % 13 35 45 armed sites 30 Inter- -

Dismissed! Victims of 2015-2018 Brutal Crackdowns in the Democratic Republic of Congo Denied Justice

DISMISSED! VICTIMS OF 2015-2018 BRUTAL CRACKDOWNS IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DENIED JUSTICE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: “Dismissed!”. A drawing by Congolese artist © Justin Kasereka (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AFR 62/2185/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 2. METHODOLOGY 9 3. BACKGROUND: POLITICAL CRISIS 10 3.1 ATTEMPTS TO AMEND THE CONSTITUTION 10 3.2 THE « GLISSEMENT »: THE LONG-DRAWN-OUT ELECTORAL PROCESS 11 3.3 ELECTIONS AT LAST 14 3.3.1 TIMELINE 15 4. VOICES OF DISSENT MUZZLED 19 4.1 ARBITRARY ARRESTS, DETENTIONS AND SYSTEMATIC BANS ON ASSEMBLIES 19 4.1.1 HARASSMENT AND ARBITRARY ARRESTS OF PRO-DEMOCRACY ACTIVISTS AND OPPONENTS 20 4.1.2 SYSTEMATIC AND UNLAWFUL BANS ON ASSEMBLY 21 4.2 RESTRICTIONS OF THE RIGHT TO SEEK AND RECEIVE INFORMATION 23 5. -

The Structural Power of Strong Pharmaceutical Patent Protection in U.S. Foreign Policy

Loyola University Chicago, School of Law LAW eCommons Faculty Publications & Other Works 2003 The trS uctural Power of Strong Pharmaceutical Patent Protection in U.S. Foreign Policy James T. Gathii Loyola University Chicago, School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/facpubs Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation James T. Gathii, The trS uctural Power of Strong Pharmaceutical Patent Protection in U.S. Foreign Policy, 7 J. Gender Race & Just. 267 (2003). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Structural Power of Strong Pharmaceutical Patent Protection in U.S. Foreign Policy James Thuo Gathii* While the Chief Justice's dissent says there are 'weapons [such as cartels or boycotts] in the arsenalsofforeign nations' sufficient to enable them to counter anticompetitive conduct ... such ... political remed[ies are] hardly available to a foreign nation faced with the monopolistic control of the supply of medicines needed for the health and safety of its people. I I. INTRODUCTION There are two distinct, albeit mutually reinforcing, stances within U.S. foreign policy on HIV/AIDS. The first of these stances favors strong international pharmaceutical patent protection, unencumbered by any restrictions, as the best alternative to ensuring availability of drugs to treat those infected with HIV/AIDS. 2 Unlike the first stance that is Assistant Professor, Albany Law School. -

Waiting for Cincinnatus: the Role of Pinochet in Post-Authoritarian Chile

Third WorldQuarterly, Vol21, No 5, pp 7 25 – 738, 2000 Waitingf orCincinnatus: the role o f Pinochetin post-authoritarian Chile GREGORYWEEKS ABSTRACT This article explains the persistent inuence of GeneralAugusto Pinochetin Chileanpolitics. After leavingthe presidency in 1990,hemanaged to fuse his personalposition with that notonly of the institution of the armybut of the armedforces as awhole,making Pinochet and the military almost indistinguishable.By doingso Pinochetsought to equateany attack onhimwith anattack onthe institution. Themilitary, in turn,accepted him as its spokesman anddefender. He viewed his role asthat of Cincinnatus,an emperortwice called to save ancientRome. Throughout the 1990sPinochetrepresented aserious obstacle to democratisation.With his intimate ties to the military institution, his inuence— perhaps even after death—can never bediscounted. InChile the transition frommilitary to civilian rule in March1990 did not erase the presenceof the armedforces in political life.The Commander in Chief of the army,General Augusto Pinochet, who had quickly taken control of the military junta installed on11 September 1973 ,becamethe self-proclaimed President ofthe Republicthe followingyear and remained in that position until hehanded the presidential sash to newlyelected Patricio Aylwin.Pinochet remainedthe headof the army,a position grantedhim foreight moreyears by laws passed in the last daysof the dictatorship. Whenhis retirement fromthe armedforces nally came to pass on10March 1998 Pinochet’ s national role still didnot end. He becamea ‘senator forli fe’( senadorvitalicio )in accordwith the 1980Constitution. Article 45provided any ex-president who had served for at least six years the right to alifetime seat in the senate. Pinochet’s presenceas armychief hada tremendousimpact oncivil – military relations in the 1990s, as at times heresorted to showsof force to extract concessions fromcivilian policymakers andto protect ‘his men’f romjudgment onhumanrights abuses. -

Report on Violations of Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law by the Allied Democratic Forces Armed

UNITED NATIONS JOINT HUMAN RIGHTS OFFICE OHCHR-MONUSCO Report on violations of human rights and international humanitarian law by the Allied Democratic Forces armed group and by members of the defense and security forces in Beni territory, North Kivu province and Irumu and Mambasa territories, Ituri province, between 1 January 2019 and 31 January 2020 July 2020 Table of contents Summary ......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Methodology and challenges encountered ............................................................................................ 7 II. Overview of the armed group Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) ................................................. 8 III. Context of the attacks in Beni territory ................................................................................................. 8 A. Evolution of the attacks from January 2015 to December 2018 .................................................. 8 B. Context of the attacks from 1 January 2019 and 31 January 2020 ............................................ 9 IV. Modus operandi............................................................................................................................................. 11 V. Human rights violations and abuses and violations of international humanitarian law . 11 A. By ADF combattants .................................................................................................................................. -

Russian Federation Interim Opinion on Constitutional

Strasbourg, 23 March 2021 CDL-AD(2021)005 Opinion No. 992/2020 Or. Engl. EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) RUSSIAN FEDERATION INTERIM OPINION ON CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENTS AND THE PROCEDURE FOR THEIR ADOPTION Adopted by the Venice Commission at its 126th Plenary Session (online, 19-20 March 2021) on the basis of comments by Mr Nicos ALIVIZATOS (Member, Greece) Ms Claire BAZY MALAURIE (Member, France) Ms Veronika BÍLKOVÁ (Member, Czech Republic) Mr Iain CAMERON (Member, Sweden) Ms Monika HERMANNS (Substitute Member, Germany) Mr Martin KUIJER (Substitute Member, Netherlands) This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. www.venice.coe.int CDL-AD(2021)005 - 2 - Contents I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 3 II. Scope of the present opinion .......................................................................................... 4 III. Chronology of the preparation and adoption of the constitutional amendments ............. 4 IV. Analysis of the procedure for the Adoption of the Constitutional Amendments .............. 6 A. Speed of preparation of the amendments - consultations ........................................... 6 B. Competence of the Constitutional Court ..................................................................... 7 C. Competence of the Constitutional Assembly .............................................................. 7 D. Ad hoc procedure .......................................................................................................