Democratic Republic of Congo: Background and U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) Reports Children in Need of Humanitarian Assistance Its First COVID-19 Confirmed Case

ef Democratic Republic of the Congo Humanitarian Situation Report No. 03 © UNICEF/UN0231603/Herrmann Reporting Period: March 2020 Highlights Situation in Numbers 9,100,000 • 10 March, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) reports children in need of humanitarian assistance its first COVID-19 confirmed case. As of 31 March 2020, 109 confirmed cases have been recorded, of which 9 deaths and 3 (OCHA, HNO 2020) recovered patients have been reported. During the reporting period, the virus has affected the province of Kinshasa and North Kivu 15,600,000 people in need • In addition to UNICEF’s Humanitarian Action for Children (HAC) (OCHA, HNO 2020) 2020 appeal of $262 million, UNICEF’s COVID-19 response plan has a funding appeal of $58 million to support UNICEF’s response 5,010,000 in WASH/Infection Prevention and Control, risk communication, and community engagement. UNICEF’s response to COVID-19 Internally displaced people can be found on the following link (HNO 2020) 6,297 • During the reporting period, 26,789 in cholera-prone zones and cases of cholera reported other epidemic-affected areas benefiting from prevention and since January response WASH packages (Ministry of Health) UNICEF’s Response and Funding Status UNICEF Appeal 2020 9% US$ 262 million 11% 21% Funding Status (in US$) 15% Funds Carry- received forward, 10% $5.5 M $28.8M 10% 49% 21% 15% Funding gap, 3% $229.3M 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% 1 Funding Overview and Partnerships UNICEF appeals for US$ 262M to sustain the provision of humanitarian services for women and children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). -

Strengthening Routine Immunization in Haut-Lomami and Tanganyika Provinces

2020 EDITION ● 2019 YEAR IN REVIEW Strengthening routine immunization in Haut-Lomami and Tanganyika provinces Stepping up commitments for routine immunization commitment to mobilize provincial resources for Launched in 2018, the Democratic Republic of Congo’s vaccination in alignment with the Kinshasa Declaration. (DRC) ‘Mashako Plan’ aims to increase immunization This past year a vaccine-derived polio (cVDPV2) rates by 15% over 18 months to vaccinate an additional epidemic persisted in DRC due to low herd immunity, 220,000 children in nine vulnerable provinces. In with 85 cases recorded in the country—including 19 response, The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) cases in Haut-Lomami and 1 case in Tanganyika. This is providing direct financial support and technical underscores the importance of partners’ continued assistance through partners to address gaps in routine work toward strengthening immunization systems and immunization in two target provinces, Haut-Lomami advocating for sustainable routine immunization and Tanganyika. financing. Below is a review of the biggest highlights of 2019 was a banner year for immunization in the DRC. In 2019 in our continued fight against polio in DRC. July, the newly elected Congolese Head of State, Félix Antoine Tshisekedi Tshilombo, hosted the National Forum on Immunization and Polio Eradication. Bringing together governors, provincial assembly presidents, ministers of health, and technical experts from all 26 provinces, he declared his vision for improving immunization systems and achieving polio elimination in front of national and international attendees. The forum culminated in the signing of the Kinshasa Declaration committing national and provincial decision-makers to take specific action to provide oversight, accountability, and resources to immunization systems. -

FINAL-Fact-Sheet-Infographic-19-Oct-2017 English Version.Ai

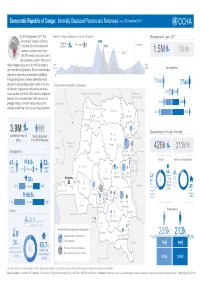

Democratic Republic of Congo: Internally Displaced Persons and Returnees (as of 30 September 2017) As of 30 September 2017, the Monthly trend of displacement in last 18 months Displacement in year 2017 Democratic Republic of Congo 432k Displaced Returnees 3rd Quarter recorded 3.9 million displaced persons 388k persons, including more than 2017 1.5M 1M 400,000 newly displaced ones in the prior three months. With over 1 million displaced persons, North Kivu remains April Sept. Demographics the most affected province. Recent months have 2016 2017 also seen large return movements, notably in 0 Tanganyika province, where authorities have 714k decided to vacate displacement sites in the city Displacement distribution by province 774k of Kalemie. In provinces affected by the Kasai 27k 29k crisis, as well, some 631,000 internally displaced CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC REPUBLIC OF persons have returned home, often to burnt or SOUTH SUDAN 263k 285k pillaged villages. Overall, armed attacks and CAMEROON clashes remain the main cause of displacement. North-Ubangi Bas-Uele 2 424k 460k Haut-Uele South-Ubangi Mongala 3.9M 45 Displacement in the last 3 months current number of Ituri 325 forcibly displaced DrDraff UGANDA 42 IDPs in the affected areas Equateur 24 REPUBLIC OF Tshopo CONGO GABON 428k 213k Demographics Tshuapa 1 024 267 North Kivu RWANDA Causes Nature of accomodation 48% 4.5% 52% Maï-Ndombe men >59 years women 71k 77k BURUNDI (1.9M) (2M) 21 % 254 45 545 104 55 Maniema South Kivu Clashes Kinshasa Sankuru and % % % 13 35 45 armed sites 30 Inter- -

World Bank Document

AID AND REFORM THE CASE OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO Public Disclosure Authorized TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abstract 2 Introduction 3 Part One: Economic Policy and Performance 3 The chaotic years following independence 3 The early Mobutu years 4 Public Disclosure Authorized The shocks of 1973-75 4 The recession years and early attempts at reform 5 The 1983 reform 5 Renewed fiscal laxity 5 The promise of structural reforms 6 The last attempt 7 Part Two: Aid and Reform 9 Financial flows and reform 9 Adequacy of the reform agenda 10 Public resource management 12 Public Disclosure Authorized The political dimension of reform 13 Conclusion 14 This paper is a contribution to the research project initiated by the Development Research Group of the World Bank on Aid and Reform in Africa. The objective of the study is to arrive at a better understanding of the causes of policy reforms and the foreign aid-reform link. The study is to focus on the real causes of reform and if and how aid in practice has encouraged, generated, influenced, supported or retarded reforms. A series of country case studies were launched to achieve the objective of the research project. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) was selected among nine other countries in Africa. The case study has been conducted by a team of two researchers, including Public Disclosure Authorized Gilbert Kiakwama, who was Congo’s Minister of Finance in 1983-85, and Jerome Chevallier. AID AND REFORM The case of the Democratic Republic of Congo ABSTRACT. i) During its first years of independence, the Democratic Republic of the Congo plunged into anarchy and became a hot spot in the cold war between the Soviet Union and the West. -

Dismissed! Victims of 2015-2018 Brutal Crackdowns in the Democratic Republic of Congo Denied Justice

DISMISSED! VICTIMS OF 2015-2018 BRUTAL CRACKDOWNS IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DENIED JUSTICE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: “Dismissed!”. A drawing by Congolese artist © Justin Kasereka (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AFR 62/2185/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 2. METHODOLOGY 9 3. BACKGROUND: POLITICAL CRISIS 10 3.1 ATTEMPTS TO AMEND THE CONSTITUTION 10 3.2 THE « GLISSEMENT »: THE LONG-DRAWN-OUT ELECTORAL PROCESS 11 3.3 ELECTIONS AT LAST 14 3.3.1 TIMELINE 15 4. VOICES OF DISSENT MUZZLED 19 4.1 ARBITRARY ARRESTS, DETENTIONS AND SYSTEMATIC BANS ON ASSEMBLIES 19 4.1.1 HARASSMENT AND ARBITRARY ARRESTS OF PRO-DEMOCRACY ACTIVISTS AND OPPONENTS 20 4.1.2 SYSTEMATIC AND UNLAWFUL BANS ON ASSEMBLY 21 4.2 RESTRICTIONS OF THE RIGHT TO SEEK AND RECEIVE INFORMATION 23 5. -

“We Will Crush You”

“We Will Crush You” The Restriction of Political Space in the Democratic Republic of Congo Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-405-2 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org November 2008 1-56432-405-2 “We Will Crush You” The Restriction of Political Space in the Democratic Republic of Congo Map of the Democratic Republic of Congo ................................................................ 1 I. Summary ............................................................................................................... 2 Methodology ....................................................................................................... 7 II. Recommendations ............................................................................................... 9 To the Congolese Government ............................................................................. 9 To the Congolese National Assembly and Senate .............................................. 10 To International Donors ..................................................................................... 10 To MONUC and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) 10 III. -

Leaders for a New Africa

LEADERS FOR A NEW AFRICA LEADERS A NEW FOR Giovanni Carbone Political leadership can be a crucial ingredient for the is Head of the ISPI Africa development of sub-Saharan Africa. The region has LEADERS FOR Programme and Professor been going through important transformations, with both of Political Science at the political landscapes and economic trajectories becoming Founded in 1934, ISPI is Università degli Studi di Milano. an independent think tank increasingly diverse. The changes underway include the A NEW AFRICA committed to the study of role of leadership and its broader impact. This volume Democrats, Autocrats, and Development international political and argues that, on the whole, African leaders and the way economic dynamics. they reach power generally do contribute to shaping edited by Giovanni Carbone It is the only Italian Institute their countries’ progresses and achievements. It also – and one of the very few in zooms in on some influential African leaders who recently introduction by Paolo Magri Europe – to combine research emerged in key states across the continent, illustrating and activities with a significant explaining the individual paths that brought them to power commitment to training, events, while reflecting on the prospects for their governments’ and global risk analysis for actions. Far from the simplistic stereotypes of immovable, companies and institutions. ineffective and greedy rulers, the resulting picture reveals ISPI favours an interdisciplinary and policy-oriented approach dynamic and rapidly evolving political scenarios with key made possible by a research implications for development in the region. team of over 50 analysts and an international network of 70 universities, think tanks, and research centres. -

Democratic Republic of the Congo

COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO 27 JANUARY 2009 UK BORDER AGENCY COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION SERVICE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO 27 JANUARY 2009 Contents_______________________________________ PREFACE LATEST NEWS EVENTS IN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO, FROM 15 DECEMBER 2008 TO 22 JANUARY 2009 Paragraphs Background information 1. GEOGRAPHY ..........................................................................................1.01 Map - DRC.....................................................................................1.05 Eastern DRC.................................................................................1.06 2. ECONOMY .............................................................................................2.01 Natural resources........................................................................2.09 3. HISTORY ...............................................................................................3.01 History to 1997.............................................................................3.01 The Laurent Kabila Regime 1997................................................3.02 The Joseph Kabila Regime 2001.................................................3.04 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS ............................................................................4.01 5. CONSTITUTION ........................................................................................5.01 6. POLITICAL SYSTEM ..................................................................................6.01 -

Kitona Operations: Rwanda's Gamble to Capture Kinshasa and The

Courtesy of Author Courtesy of Author of Courtesy Rwandan Patriotic Army soldiers during 1998 Congo war and insurgency Rwandan Patriotic Army soldiers guard refugees streaming toward collection point near Rwerere during Rwanda insurgency, 1998 The Kitona Operation RWANDA’S GAMBLE TO CAPTURE KINSHASA AND THE MIsrEADING OF An “ALLY” By JAMES STEJSKAL One who is not acquainted with the designs of his neighbors should not enter into alliances with them. —SUN TZU James Stejskal is a Consultant on International Political and Security Affairs and a Military Historian. He was present at the U.S. Embassy in Kigali, Rwanda, from 1997 to 2000, and witnessed the events of the Second Congo War. He is a retired Foreign Service Officer (Political Officer) and retired from the U.S. Army as a Special Forces Warrant Officer in 1996. He is currently working as a Consulting Historian for the Namib Battlefield Heritage Project. ndupress.ndu.edu issue 68, 1 st quarter 2013 / JFQ 99 RECALL | The Kitona Operation n early August 1998, a white Boeing remain hurdles that must be confronted by Uganda, DRC in 1998 remained a safe haven 727 commercial airliner touched down U.S. planners and decisionmakers when for rebels who represented a threat to their unannounced and without warning considering military operations in today’s respective nations. Angola had shared this at the Kitona military airbase in Africa. Rwanda’s foray into DRC in 1998 also concern in 1996, and its dominant security I illustrates the consequences of a failure to imperative remained an ongoing civil war the southwestern Bas Congo region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). -

Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)

Democratic Republic of the Congo Humanitarian Situation Report No. 04 © UNICEF/Kambale Reporting Period: April 2020 Highlights Situation in Numbers 9,100,000 • After 52 days without any Ebola confirmed cases, one new Ebola children in need of case was reported in Beni, North Kivu province on the 10th of April humanitarian assistance 2020, followed by another confirmed case on the 12th of April. UNICEF continues its response to the DRC’s 10th Ebola outbreak. (OCHA, HNO 2020) The latest Ebola situation report can be found following this link 15,600,000 • Since the identification of confirmed COVID-19 cases in the DRC, people in need schools have closed across the country to limit the spread of the (OCHA, HNO 2020) virus. Among other increased needs, the COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbates the significant needs in education related to access to quality education. The latest COVID-19 situation report can be found 5,010,000 following this link Internally displaced people (HNO 2020) • UNICEF has provided life-saving emergency packages in NFI/Shelter 7,702 to more than 60,000 households while ensuring COVID-19 mitigation measures. cases of cholera reported since January (Ministry of Health) UNICEF’s Response and Funding Status UNICEF Appeal 2020 14% US$ 262 million 12% 38% Funding Status (in US$) Funds 15% received Carry- $14.2 M 50% forward, $28.8M 16% 53% 34% Funding 15% gap, $220.9 M 7% 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% 1 Funding Overview and Partnerships UNICEF appeals for US$ 262M to sustain the provision of humanitarian services for women and children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). -

Democratic Republic of Congo OGN V9.0 23 December 2008

Democratic Republic of Congo OGN v9.0 23 December 2008 OPERATIONAL GUIDANCE NOTE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO CONTENTS 1. Introduction 1.1 – 1.4 2. Country assessment 2.1 – 2.10 3. Main categories of claims 3.1 – 3.5 Opposition political activists or members of former rebel forces 3.6 Members of non-government organisations (NGOs) 3.7 Non-Banyamulenge Tutsis 3.8 Banyamulenge Tutsis 3.9 General situation in the Ituri region: people of Hema or Lendu ethnicity 3.10 North Kivu 3.11 Prison conditions 3.12 4. Discretionary Leave 4.1 – 4.2 Minors claiming in their own right 4.3 Medical treatment 4.4 5. Returns 5.1 – 5.3 6. List of source documents 1. Introduction 1.1 This document evaluates the general, political and human rights situation in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and provides guidance on the nature and handling of the most common types of claims received from nationals/residents of that country, including whether claims are or are not likely to justify the granting of asylum, Humanitarian Protection or Discretionary Leave. Case owners must refer to the relevant Asylum Instructions for further details of the policy on these areas. 1.2 This guidance must also be read in conjunction with any COI Service DRC Country of Origin Information at: http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/country_reports.html 1.3 Claims should be considered on an individual basis, but taking full account of the guidance contained in this document. In considering claims where the main applicant has dependent family members who are a part of his/her claim, account must be taken of the situation of all the dependent family members included in the claim in accordance with the Asylum Instructions on Article 8 ECHR. -

Assessing the Effectiveness of the United Nations Mission

Assessing the of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO Publisher: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs Copyright: © Norwegian Institute of International Affairs 2019 ISBN: 978-82-7002-346-2 Any views expressed in this publication are those of the author. They should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. The text may not be re-published in part or in full without the permission of NUPI and the authors. Visiting address: C.J. Hambros plass 2d Address: P.O. Box 8159 Dep. NO-0033 Oslo, Norway Internet: effectivepeaceops.net | www.nupi.no E-mail: [email protected] Fax: [+ 47] 22 99 40 50 Tel: [+ 47] 22 99 40 00 Assessing the Effectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC (MONUC-MONUSCO) Lead Author Dr Alexandra Novosseloff, International Peace Institute (IPI), New York and Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Oslo Co-authors Dr Adriana Erthal Abdenur, Igarapé Institute, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Prof. Thomas Mandrup, Stellenbosch University, South Africa, and Royal Danish Defence College, Copenhagen Aaron Pangburn, Social Science Research Council (SSRC), New York Data Contributors Paul von Chamier, Center on International Cooperation (CIC), New York University, New York EPON Series Editor Dr Cedric de Coning, NUPI External Reference Group Dr Tatiana Carayannis, SSRC, New York Lisa Sharland, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Canberra Dr Charles Hunt, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University, Australia Adam Day, Centre for Policy Research, UN University, New York Cover photo: UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti UN Photo/ Abel Kavanagh Contents Acknowledgements 5 Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 13 The effectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC across eight critical dimensions 14 Strategic and Operational Impact of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Constraints and Challenges of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Current Dilemmas 19 Introduction 21 Section 1.