The Intertwining Letters, Lives, and Literature of Jorge Carrera Andrade and Pablo Neruda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mujer, Tradición Y Conciencia Histórica En Gertrudis Gómez De Avellaneda

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2017 MUJER, TRADICIÓN Y CONCIENCIA HISTÓRICA EN GERTRUDIS GÓMEZ DE AVELLANEDA Ana Lydia Barrios University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Latin American Literature Commons, and the Spanish Literature Commons Recommended Citation Barrios, Ana Lydia, "MUJER, TRADICIÓN Y CONCIENCIA HISTÓRICA EN GERTRUDIS GÓMEZ DE AVELLANEDA. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/4441 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Ana Lydia Barrios entitled "MUJER, TRADICIÓN Y CONCIENCIA HISTÓRICA EN GERTRUDIS GÓMEZ DE AVELLANEDA." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Modern Foreign Languages. Óscar Rivera-Rodas, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Michael Handelsman, Nuria Cruz-Cámara, Jacqueline Avila Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) MUJER, TRADICIÓN Y CONCIENCIA HISTÓRICA EN GERTRUDIS GÓMEZ DE AVELLANEDA A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Ana Lydia Barrios May 2017 ii Copyright © 2017 by Ana Lydia Barrios All rights reserved. -

Alessandro Rocco Università Di Bari, Italia

REVISTA DE CRÍTICA LITERARIA LATINOAMERICANA Año XXXVII, No 73. Lima-Boston, 1er semestre de 2011, pp. 229-252 JOSÉ REVUELTAS, ESCRITOR DE CINE: EL GUION LA OTRA Alessandro Rocco Università di Bari, Italia Resumen En 1944, el escritor José Revueltas empieza su aventura en el cine mexicano. A partir de esa fecha, y hasta el año 1960, Revueltas aparecerá como argumentista y/o adaptador en los créditos de veinticuatro películas, a las que hay que añadir, en 1975, la adaptación de El apando. Existen también cuatro guiones completos publicados (La otra, Tierra y libertad, Los albañiles, El apando). Este artículo pro- pone un análisis crítico del guion de José Revueltas, La otra (1946), con el ob- jetivo de estudiar su funcionamiento narrativo en cuanto texto fílmico; y con el intento de colocarlo en el contexto de la producción narrativa de Revueltas, en cuanto texto narrativo de autor. Presencia del espejo y del reflejo como elemento central en la representación de la temática de la identidad y del doble; espacio de la cárcel como signo y representación de la enajenación; culpa (fratricidio) y castigo; actitud piadosa hacia el personaje (femenino) culpable: estos elementos demuestran que el guion La otra no es un texto extraño al universo narrativo y a las preocupaciones literarias de José Revueltas. Palabras clave: cine y literatura, guion cinematográfico, relato fílmico, José Re- vueltas, Roberto Gavaldón, La otra, cine mexicano. Abstract In 1944 the Mexican writer José Revueltas began his adventure in Mexican ci- nema. Since then, and until 1960, Revueltas will appear as screenwriter in the credits of twenty-four Mexican movies, and in one more in 1975: the adapta- tion of his own novel El apando. -

Lista De Inscripciones Lista De Inscrições Entry List

LISTA DE INSCRIPCIONES La siguiente información, incluyendo los nombres específicos de las categorías, números de categorías y los números de votación, son confidenciales y propiedad de la Academia Latina de la Grabación. Esta información no podrá ser utilizada, divulgada, publicada o distribuída para ningún propósito. LISTA DE INSCRIÇÕES As sequintes informações, incluindo nomes específicos das categorias, o número de categorias e os números da votação, são confidenciais e direitos autorais pela Academia Latina de Gravação. Estas informações não podem ser utlizadas, divulgadas, publicadas ou distribuídas para qualquer finalidade. ENTRY LIST The following information, including specific category names, category numbers and balloting numbers, is confidential and proprietary information belonging to The Latin Recording Academy. Such information may not be used, disclosed, published or otherwise distributed for any purpose. REGLAS SOBRE LA SOLICITACION DE VOTOS Miembros de La Academia Latina de la Grabación, otros profesionales de la industria, y compañías disqueras no tienen prohibido promocionar sus lanzamientos durante la temporada de voto de los Latin GRAMMY®. Pero, a fin de proteger la integridad del proceso de votación y cuidar la información para ponerse en contacto con los Miembros, es crucial que las siguientes reglas sean entendidas y observadas. • La Academia Latina de la Grabación no divulga la información de contacto de sus Miembros. • Mientras comunicados de prensa y avisos del tipo “para su consideración” no están prohibidos, -

![Esto No Es Una Casa. La Casa Sin Salida En El Cine De Roman Polanski" [En Línea]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9477/esto-no-es-una-casa-la-casa-sin-salida-en-el-cine-de-roman-polanski-en-l%C3%ADnea-489477.webp)

Esto No Es Una Casa. La Casa Sin Salida En El Cine De Roman Polanski" [En Línea]

RODRÍGUEZ DE PARTEARROYO, Manuela (2014): "Esto no es una casa. La casa sin salida en el cine de Roman Polanski" [en línea]. En: Ángulo Recto. Revista de estudios sobre la ciudad como espacio plural, vol. 6, núm. 1, pp. 77-96. En: http://www.ucm.es/info/angulo/volumen/Volumen06-1/varia01.htm. ISSN: 1989-4015 http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/rev_ANRE.2014.v6.n1.45324 Esto no es una casa. La casa sin salida en el cine de Roman Polanski Manuela RODRÍGUEZ DE PARTEARROYO Departamento de Filología Italiana Universidad Complutense de Madrid [email protected] Recibido: 13/09/2013 Modificado: 31/03/2014 Aceptado: 25/04/2014 Resumen Desde sus orígenes, el cine de Roman Polanski ha mantenido intacto su poder de fascinación sobre el espectador cinematográfico, tanto por su incansable modernidad, como por la inevitable polémica que siempre arrastran sus películas. En este caso, pretenderemos acercarnos a dos comedias, escasas en su filmografía, como son What? (1972) y Carnage (2011), muy distantes en el tiempo aunque con interesantes coincidencias temáticas y narrativas. Nuestro interés primordial será ahondar en su retrato de las figuras femeninas de ambas obras y su ubicación, física y metafórica, en el espacio de la casa. Siguiendo la estela de maestros como Luis Buñuel, Marco Ferreri o Stanley Kubrick, Polanski encerrará a sus mujeres en un refugio hostil y sin salida para que vaya cayéndose progresivamente la máscara de la sociedad moderna, dejando salir, poco a poco, al animal primitivo que nunca hemos dejado de ser. Esto no es una casa, sino una balsa llena de náufragos tratando de sobrevivir. -

EL CAMBIO CLIMÁTICO Y LA GRAN INACCIÓN Nuevas Perspectivas Sindicales

Documento de trabajo No.2 EL CAMBIO CLIMÁTICO Y LA GRAN INACCIÓN Nuevas perspectivas sindicales Índice El cambio climático y la gran inacción Nuevas perspectivas sindicales Varsovia: El fin del comienzo.......................................................................................................2 La CMNUCC y el proceso de Kioto..............................................................................................4 Fe en el mercado......................................................................................................................5 Trabajos, transición justa, diálogo social...................................................................................5 La economía verde y el PNUMA.........................................................................................7 La gran recesión y la alternativa verde.....................................................................................8 Ciencia y solidaridad.....................................................................................................................9 Tiro al blanco: La AFL-CIO.............................................................................................................9 El fiasco de Copenhague—y después......................................................................................10 Emisiones de países en vías de desarrollo..............................................................................11 Déficit de emisiones...................................................................................................................12 -

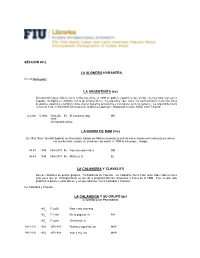

Lecuona Cuban Boys

SECCION 03 L LA ALONDRA HABANERA Ver: El Madrugador LA ARGENTINITA (es) Encarnación López Júlvez, nació en Buenos Aires en 1898 de padres españoles, que siendo ella muy niña regresan a España. Su figura se confunde con la de Antonia Mercé, “La argentina”, que como ella nació también en Buenos Aires de padres españoles y también como ella fue bailarina famosísima y coreógrafa, pero no cantante. La Argentinita murió en Nueva York en 9/24/1945.Diccionario de la Música Española e Hispanoamericana, SGAE 2000 T-6 p.66. OJ-280 5/1932 GVA-AE- Es El manisero / prg MS 3888 CD Sonifolk 20062 LA BANDA DE SAM (me) En 1992 “Sam” (Serafín Espinal) de Naucalpan, Estado de México,comienza su carrera con su banda rock comienza su carrera con mucho éxito, aunque un accidente casi mortal en 1999 la interumpe…Google. 48-48 1949 Nick 0011 Me Aquellos ojos verdes NM 46-49 1949 Nick 0011 Me María La O EL LA CALANDRIA Y CLAVELITO Duo de cantantes de puntos guajiros. Ya hablamos de Clavelito. La Calandria, Nena Cruz, debe haber sido un poco más joven que él. Protagonizaron en los ’40 el programa Rincón campesino a traves de la CMQ. Pese a esto, sólo grabaron al parecer, estos discos, y los que aparecen como Calandria y Clavelito. Ver:Calandria y Clavelito LA CALANDRIA Y SU GRUPO (pr) c/ Juanito y Los Parranderos 195_ P 2250 Reto / seis chorreao 195_ P 2268 Me la pagarás / b RH 195_ P 2268 Clemencia / b MV-2125 1953 VRV-857 Rubias y trigueñas / pc MAP MV-2126 1953 VRV-868 Ayer y hoy / pc MAP LA CHAPINA. -

Poemario Del Círculo María L. Pérez EN HOMENAJE a LA Benemérita Escuela Normal De

Poemario del Círculo María L. Pérez EN HOMENAJE A LA Benemérita Escuela Normal de Coahuila Ilustración adaptada de la Publicación “3 Vidas Paralelas” de el Profr. Gustavo Ramírez Padilla Mayo de 1976 POEMARIO DEL CÍRCULO MARÍA L. PÉREZ EN HOMENAJE A LA “BENC” Prólogo Nos enorgullece el poder aportar las composiciones poéticas que constituyen esta Antología: “Benemérita”, dedicada precisamente a la Benemérita Escuela Normal del Estado de Coahuila. Cientos de generaciones han pasado por sus aulas, y han cumplido con el excelso y sublime labor de la docencia, tanto en la acción académica, como en la acción formativa. La Benemérita Escuela Normal, es baluarte y pilar en la formación y orientación de nuestra niñez y nuestra juventud. Su prestigio no es sólo en nuestro Estado, sino también en todo México. Rogamos que la Institución siga manteniendo y proyectando su labor fecunda, basada en la honestidad y la decencia. Vemos a un México triunfante y próspero, teniendo como baluarte a Instituciones como la Benemérita Escuela Normal, que mantiene en alto el principio de la dignidad. Recordando el lema de la Institución, debe dejarnos la pauta para seguir adelante: “El trabajo todo lo vence”, y eso nos hace ser triunfadores. Con ésta Antología el Círculo Literario “María L. Pérez” rinde homenaje a la Benemérita Institución. Luis Ríos Schroeder. (Presidente del Círculo Literario) Benemérita Escuela Normal de Coahuila - 2014 Diseño de Portada e Interior: L.D.G. Fabiola Lizbeth Castaño Ordóñez Impreso y Encuadernado: Talleres Gráficos de la BENC 5 POEMARIO DEL CÍRCULO MARÍA L. PÉREZ EN HOMENAJE A LA “BENC” POEMARIO DEL CÍRCULO MARÍA L. -

El Debate 19341107

EL TIEMPO (S. Meteorológico N.).—Probable hasta las seis de la tarde de hoy. Centro y Oeste de Andalucía: Vientos, del Noroeste y cielo nuboso. Resto de España: La hechicera del Monte Melton Vientos del Oeste y algunos chubascos. Temperatura: dramática y sugestiva novela, que se ptiDlTca Tnte^a máxima de ayer, 20 en Castellón y Murcia; mínima, 1 l en la gran revlsCa en Zamora. En Madrid: máxima, 12,5 (12,50 ra.); míni ma, 5 (5,40 m.). (Véase en séptima plana el Boletín Meteorológico.) LECTURAS PARA TODOS E Primera paiie, esta semana. Segunda parle, la semana prSuma. MADRID—Año XXIV.—Núm. 7.783 * Miércoles 7 ae noviembre de 1984 CINCO EDICIONES DIARIAS Apartado 466. — Red. y Admón., ALFONSO XI, 4.—Teléfonos 21090, 21092, 21093, 21094, 21095 y 21096 La huelga general decretada por la C. N. T. ha fracasado rotundamente Ante otro intento criminal LO DEL DÍA ¡Consejo de guerra para Las Caries otorgaron su confianza al Gobierno después de un •• ^«^ •• Intento de lanzar a los obreros a la huelga general en Zaragoza. Con decir Primero, la responsabilidad los diputados general se ahorran muchas aclaraciones. Quiere decirse que es revolucionaria civil de la revolución discurso de Gil Robles y que, empezada en estos momentos, guarda estrecha conexión con la pasada La Sala segunda se inhibe en el • • mmm • • intentona y la continúa. No hay por qué sentir alarma de ninguna especie. Pero Se empiezan a proponer arbitrios sí hay razón para que la sociedad y el Gobierno, como llamado a defenderla, para la reconstrucción de Oviedo des caso de Prieto truida, y de la maltrecha zona de As —«- - "Cuando se venza la nueva insurrección, que será la última, se exigirán tomen buena cuenta de lo que ocurre y aprovechen muy seriamente la lección. -

Versos Electrónicos II: 2008-2010

Versos electrónicos II: 2008-2010 Ernesto Oregel Versos electrónicos II 2008-2010 Ernesto Oregel Aritza Press Massachusetts 2014 -i- Copyright © 2014 by Oregel Vega, Ernesto First Edition All rights reserved. No part of this book shall be reproduced, stored in any retrieval system, or transmitted by any means without written permission from the author. Other books by Ernesto Oregel: Juncos de mi río/Reeds of my river (1999) 55 Sonetos: 1962-2002 (2002) Caballo negro: Cantos de la muerte (2003) Blond Angels/Ángeles blondos (2007) Canto a México (2011) Versos electrónicos I: 2002-2007 To contact the author: [email protected] www.lrc.salemstate.edu/oregel -ii- Índice Índice ............................................................................. iii Índice de imágenes ....................................................... viii IMÁGENES .........................................................XI VERSOS DE 2008 ................................................ 1 Enero .............................................................................. 3 De tus cuatro elegías ....................................................... 4 Mio Omaggio a Don Bosco ............................................... 5 Canto a Nina al pie del mar ............................................. 6 Primer aniversario ........................................................... 7 Domani giovedì sarò da te ................................................ 8 Filosofando ...................................................................... 9 Prosa y rima ................................................................. -

La Revista De Taos, 05-05-1911 Jose ́ Montaner

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Revista de Taos, 1905-1922 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 5-5-1911 La Revista de Taos, 05-05-1911 Jose ́ Montaner Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/revista_taos_news Recommended Citation Montaner, Jose.́ "La Revista de Taos, 05-05-1911." (1911). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/revista_taos_news/839 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Revista de Taos, 1905-1922 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. t. n, loin the .Cxy..x-- , v is I run. iaza otor P f Ktjl 'kiA J& ) Mjr--n Es la tienda nueva en donde ::N " U tV - PV jf VCOCf.í-'ív- SttW-r- V' pa, Vdiu, Linos, Ud. p::ede comprar mejores WÍ V3-"- - 5!. efaetoá y á mejores precios. Tenemos la mejor marca j , '! f - Nacional y Extranjera de zapatos para Hombres, fe f V SjraS' i J J'- L VS t 7 )Y VA---- K S-- . l. Frescos. LOS Señoras y Sefioritaa. V - Siempra LEV1S-LOW- E CO., Taos, New Mexico Año X. Puilished by Taos Printing a Publishing Co. Taos, Nuevo México, U. S. A., Viernes 5 da Mayo, 1911 JOSE MONTANER, Editor Ho. 13 COLOCACION CUENTO U VOZ DLMi CAPITAL DEL DICHO AL HECHO ALEGORICO CORTE DE DISTRITO De la Piedra Angular do HAY GRAN TRECHO El Dios Virján en Muevo la Hueva Catedral La Tregua Oficial. -

THE REDISCOVERY of JORGE CARRERA ANDRADE This Is a Very Momentous Day at Assumption College As the Life and Literary Works of Jo

THE REDISCOVERY OF JORGE CARRERA ANDRADE This is a very momentous day at Assumption College as the life and literary works of Jorge Carrera Andrade are celebrated through the good graces of our friend Juan Carlos Grijalva . I have read and translated Latin American literature for two decades and yet in 1998 the name of Jorge Carrera Andrade was not prominent in the universe of important Latin American writers available in English translation. I did not know who he was. I then discovered Carrera Andrade in an anthology of European poets published in the 1960s -for he had already lived on and off for decades in Paris as Consul General, Ambassador to France and employed at UNESCO- and I was immediately taken by one poem in this collection: LIFE OF THE GRASSHOPPER Always an invalid he wanders through the field on green crutches. Since five o'clock the stream from a star has filled the grasshopper's tiny pitcher. A laborer, he fishes each day with his antenna in the rivers of air. A misanthrope, at night he hangs the flicker of his chirp in a house of grass. Leaf rolled up and alive, the grasshopper keeps the music of the world written inside. The images of Carrera Andrade are so simple and clear even a child can see and understand. His poetry is the result of the poet’s intense magical engagement with nature, with the Indians of his native Ecuador, with the landscape of Ecuador itself and other places of the world he has traveled. I began researching this poet and fell in love with his work but continued to puzzle over the fact he was unknown in English during my own era and not represented in the major anthologies of Latin American poetry. -

Los Dioses Hechiceros / Armando Barona Mesa

Armando Barona Mesa Armando Barona Mesa varios libros de ensayos histó- El autor de esta obra, Arman- ricos: Momentos y personajes do Barona Mesa, es un abogado de la historia (tres tomos), La colombiano nacido en el Va- separación de Panamá, al igual lle del Cauca, con un dilatado que otro volumen de variadas “... los dioses sirven a las necesidades de los hom- ejercicio profesional, especial- prosas, Notas del caminante, El bres, sus creadores, porque los hombres son sus mente en el campo del dere- Magnicidio de Sucre, un tema criaturas. Desde ese ángulo válido de observación, cho penal. Hombre de estudio, aún sensible, doloroso y en es preciso decir que los dioses sí existen y el hombre también ha transitado por el cierta manera urticante, y tres no puede vivir sin ellos, como que los dioses acuden terreno de la política, habiendo HECHICEROS LosLos libros más de poemas, en todos a su llamado para salvarlo de los grandes y peque- desempeñado todos los cargos los cuales muestra una escritura ños males que asedian la vida. Y porque además, que otorga la democracia en elegante, fi na y muy bien ela- son mágicos. Hechiceros, para ser más exactos”. las corporaciones públicas. De borada. Es un escritor versátil, paso ha ejercido la diplomacia erudito y severo. como embajador de su país en varias oportunidades. DIOSES DIOSESDIOSES ISBN:978-958-98247-6-4 Consagrado a la historia HECHICEROSHECHICEROS como una pasión, es autor de Los Continúa en la segunda solapa varios libros de ensayos histó- El autor de esta obra, Arman- ricos: Momentos y personajes do Barona Mesa, es un abogado de la historia (tres tomos), La colombiano nacido en el Va- separación de Panamá, al igual lle del Cauca, con un dilatado que otro volumen de variadas “..