Introduction of Domestic Reindeer Into Alaska

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alaska Peninsula and Aleutian Islands Management Area Herring Sac Roe and Food and Bait Fisheries Annual Management Report, 2002

ALASKA PENINSULA AND ALEUTIAN ISLANDS MANAGEMENT AREA HERRING SAC ROE AND FOOD AND BAIT FISHERIES ANNUAL MANAGEMENT REPORT, 2002 By Matthew T. Ford Charles Burkey Jr. and Robert L. Murphy Regional Information Report1 No. 4K03-11 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Commercial Fisheries 211 Mission Road Kodiak, Alaska 99615 March 2003 1 The Regional Information Report Series was established in 1987 to provide an information access system for all unpublished division reports. These reports frequently serve diverse ad hoc informational purposes or archive basic uninterpreted data. To accommodate timely reporting of recently collected information, reports in this series undergo only limited internal review and may contain preliminary data; this information may be subsequently finalized and published in the formal literature. Consequently, these reports should not be cited without prior approval of the author or the Division of Commercial Fisheries. AUTHORS Matthew T. Ford is the Alaska Peninsula and Aleutian Islands Management Area Assistant Herring Biologist and Alaska Peninsula-Southeastern District Salmon Assistant Management Biologist for Region IV, Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Commercial Fisheries, 211 Mission Road, Kodiak, Alaska, 99615. Charles Burkey Jr. is the Alaska Peninsula and Aleutian Islands Management Areas Herring Biologist and Alaska Peninsula-Southeastern District Salmon Management Biologist for Region IV, Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Commercial Fisheries, 211 Mission Road, Kodiak, Alaska, 99615. Robert L. Murphy is the North Alaska Peninsula Area Herring Biologist and North Alaska Peninsula Salmon Management Biologist for Region IV, Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Commercial Fisheries, 211 Mission Road, Kodiak, Alaska, 99615. -

Resource Utilization in Unalaska, Aleutian Islands, Alaska

RESOURCE UTILIZATION IN UNALASKA, ALEUTIAN ISLANDS, ALASKA Douglas W. Veltre, Ph. D. Mary J. Veltre, B.A. Technical Paper Number 58 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Subsistence October 23, 1982 Contract 824790 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report would not have been possible to produce without the generous support the authors received from many residents of Unalaska. Numerous individuals graciously shared their time and knowledge, and the Ounalashka Corporation,. in particular, deserves special thanks for assistance with housing and transportation. Thanks go too to Linda Ellanna, Deputy Director of the Division of Subsistence, who provided continuing support throughout this project, and to those individuals who offered valuable comments on an earlier draft of this report. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS. ii Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION . 1 Purpose ..................... 1 Research objectives ............... 4 Research methods 6 Discussion of rese~r~h'm~tho~oio~y' ........ ...... 8 Organization of the report ........... 10 2 BACKGROUNDON ALEUT RESOURCE UTILIZATION . 11 Introduction ............... 11 Aleut distribuiiin' ............... 11 Precontact resource is: ba;tgr;ls' . 12 The early postcontact period .......... 19 Conclusions ................... 19 3 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND. 23 Introduction ........................... 23 The precontact'plrioi . 23 The Russian period ............... 25 The American period ............... 30 Unalaska community profile. ........... 37 Conclusions ................... 38 4 THE NATURAL SETTING ............... -

A Psycho-Social Exploration of Trans-Racial Adoptive Subjectivity

A Psycho-social Exploration of Trans-racial Adoptive Subjectivity Cecilia Love This thesis is submitted to Cardiff University in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Social Work Doctorate Cardiff University Abstract The aim of this thesis is to convey a psycho-social and experiential understanding of the lived experience of trans-racial adoption. As a woman that was adopted as a baby from Malaysia by Caucasian parents during the 1970s, the personal experience of the phenomenon of trans-racial adoption has been integral to the theoretical foundations and overall research approach of this study. The primary aim of this study has been one that has sought to deepen understanding of the affective dimensions involved in being a trans-racially adoptive family member from both the perspective of the adoptive mother and the adoptee. The concept of trans-racial adoptive subjectivity is informed by phenomenological and psychoanalytic thinking and assumes an embodied subject that is embedded in a relational and material world. The analytical focus therefore prioritises understanding the historical, social and political processes that engage the body in particular ways that we can understand as being trans-racially adopted. The research framework assumes a psycho-social methodological framework that has prioritised depth of understanding experience. Six sets of trans-racially adopted adults and their adoptive mothers were engaged where each family members was interviewed over a period of six months, four times each. Influenced by the relational psychoanalytic tradition, the notion of inter-subjectivity was central to the methodological process. The research interview encounters therefore assumed a two person psychology where the feelings I experienced as the researcher were considered as important forms of research data. -

CHAPTER 18: the RETURN 257 with the Body of Martha Newell Was Lifted Aboard for Its Journey Home

Chapter 18 The Return he most dramatic account of the voyage back to the islands appears in a letter Marion V. Benedict wrote.1 She was a “special assistant” assigned to T Akutan; that is, she was the village school-teacher. Just as the Branch was about to sail on April 15, George Dushkin approached her and her husband and requested a telegram be sent to the administrator of the church in Sitka, Archimandrite John Zlobin, to pray for them while they traveled.2 Benedict was impressed by this request. “Did I ever tell you,” she wrote, “these are the nicest people we have ever worked with? They had burned their altar from the church at Ward Lake and were taking the ashes with them to be buried under the church in their own village.” As a matter of fact, Zlobin had written to Anfesia Shapsnikoff at Burnett Inlet on April 9. “Also I calling on you and your children,” he wrote in halting English, “Bless of God befor you move from Burnett Inlet and during you move from Burnett all way till you come to Unalaska, let God and Mother of God help you and save you....”3 In a postscript he sent a blessing to the church committee and to the entire congregation. Despite the illness of Chief Mark Petikoff, joy pervaded the ship as it pulled away from Ketchikan. Children flooded the decks and explored every cabin and corner, to the alarm of the captain who soon arranged to have certain areas made off limits. Unanga{ assisted preparing and serving meals and helping with other chores. -

Aleuts: an Outline of the Ethnic History

i Aleuts: An Outline of the Ethnic History Roza G. Lyapunova Translated by Richard L. Bland ii As the nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has re- sponsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural and cultural resources. This includes fostering the wisest use of our land and water resources, protecting our fish and wildlife, preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places, and providing for enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The Shared Beringian Heritage Program at the National Park Service is an international program that rec- ognizes and celebrates the natural resources and cultural heritage shared by the United States and Russia on both sides of the Bering Strait. The program seeks local, national, and international participation in the preservation and understanding of natural resources and protected lands and works to sustain and protect the cultural traditions and subsistence lifestyle of the Native peoples of the Beringia region. Aleuts: An Outline of the Ethnic History Author: Roza G. Lyapunova English translation by Richard L. Bland 2017 ISBN-13: 978-0-9965837-1-8 This book’s publication and translations were funded by the National Park Service, Shared Beringian Heritage Program. The book is provided without charge by the National Park Service. To order additional copies, please contact the Shared Beringian Heritage Program ([email protected]). National Park Service Shared Beringian Heritage Program © The Russian text of Aleuts: An Outline of the Ethnic History by Roza G. Lyapunova (Leningrad: Izdatel’stvo “Nauka” leningradskoe otdelenie, 1987), was translated into English by Richard L. -

Festivals and Ceremonies of the Alaskan Eskimos: Historical and Ethnographic Sources, 1814-1940

Festivals and Ceremonies of the Alaskan Eskimos: Historical and Ethnographic Sources, 1814-1940 Jesús SALIUS GUMÀ Department of Prehistory, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona AGREST Research Group [email protected] Recibido: 15 de octubre de 2012 Aceptado: 16 de enero de 2013 ABSTRACT The main objective of this article is to shed light on the festive and ceremonial events of some of the Eskimo cultures of Alaska through a review of the ethnohistorical documents at our disposal. The study centers on the ancient societies of the Alutiiq, Yup’ik and a part of the Inupiat, communities that share a series of com- mon features, and sees their festive and ceremonial activities as components of the strategies implemented to maintain control over social reproduction. This review of the historical and ethnographic sources identifies the authors and the studies that provide the most pertinent data on the subject. Key words: Ethnohistory, social reproduction, musical behaviors, Alaska Eskimo. Festivales y ceremonias de los esquimales de Alaska: fuentes históricas y etnográficas, 1814-1940 RESUMEN El objeto de este artículo es arrojar luz sobre las fiestas y ceremonias de algunas culturas esquimales de Alaska a través de la revisión de documentos etnohistóricos a nuestra disposición. La investigación se centra sobre las antiguas sociedades de los alutiiq, yup’ik y parte de los inupiat, comunidades que tienen una serie de rasgos comunes y contemplan sus actividades festivas y ceremoniales como parte de estrategias para mantener el control sobre la reproducción social. Esta revisión de fuentes históricas y etnográficas identifica a los autores y a los estudios que proporcionan los datos más significativos sobre el tema. -

Walking Tour

Visit Historic Main Street in Jackson The Heart of the Gold Country on Scenic Highways 88 & 49 FEATURING ANTIQUES • ART • BOOKS CRAFTS • FINE WINES GOURMET FOODS HISTORIC HOTEL & SALOON RESTAURANTS • 1 Amador County Museum 24 Wells Fargo Bank SERVICES • UNIQUE SHOPS 2 Jewish Synagogue Monument 25 Footbridge 3 The A. Fantozzi Marble Headstone Works 26 National Hotel 4 Jackson Protestant or Community Cemetery 27 12 Water Street 5 Historic Jewish Cemetery 28 Masonic Hall 6 Jackson Catholic Cemetery 29 Oddfellows’ Hall 7 St. Sava Serbian Orthodox Church 30 Add Art PLUS 8 The Hamilton Tract Victorian Subdivision 31 Rosebud’s Cafe 9 First Catholic Church Site 32 Celtic Knot 10 Early Town Rock Walls 33 Mother Lode Market 11 Fletcher Alley 34 Trassare Jewelry Store 12 Cafe DeCoco 35 Stecklers Building ANNUAL EVENTS 13 Globe Hotel Building 36 Old Jail Site 14 Jackson Cleaners Building 37 Native Son’s Hall COUNTY MUSEUM 15 Native Daughters’...Birthplace 38 Constitution Saloon KENNEDY GOLD MINE TOURS 16 Sidewalk Plaque 39 Toma & Associates 17 The Bottle Shop 40 Old Amador County Court House TAILING WHEELS PARK 18 41 Main Street 41 The Law Office & 19 Gold Mine Jewelers 42 St. Patrick’s Catholic Church & Rectory 20 35 Main Street 43 215 Court Street FRIENDLY PEOPLE 21 29-33 Main Street 44 The Jackson United Methodist Church 22 The Central Hotel 45 Parsonage, United Methodist Church 23 Trader Stan Bottileas, Jackson’s Creek Walking Tour Jackson – that city which gold, girls, gambling, When Amador was organized as a new county gastronomic delights and government has kept in 1854, Jackson eked out a win over Volcano to of lively for over 150 years – was born in the gold become the new county’s county seat. -

An Investigation Into British Neutrality During the American Civil War 1861-65

AN INVESTIGATION INTO BRITISH NEUTRALITY DURING THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR 1861-65 BY REBECCA CHRISTINE ROBERTS-GAWEN A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MA by Research Department of History University of Birmingham November 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis sought to investigate why the British retained their policy of neutrality throughout the American Civil War, 1861-65, and whether the lack of intervention suggested British apathy towards the conflict. It discovered that British intervention was possible in a number of instances, such as the Trent Affair of 1861, but deliberately obstructed Federal diplomacy, such as the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863. This thesis suggests that the British public lacked substantial and sustained support for intervention. Some studies have suggested that the Union Blockade of Southern ports may have tempted British intervention. This thesis demonstrates how the British sought and implemented replacement cotton to support the British textile industry. This study also demonstrates that, by the outbreak of the Civil War, British society lacked substantial support for foreign abolitionists’’ campaigns, thus making American slavery a poorly supported reason for intervention. -

Annual Report Noaa Ocseap Ecological Studies Of

ANNUAL REPORT NOAA OCSEAP Contract No. 03-6-022-35210 Research Unit No. 460 ECOLOGICAL STUDIES OF COLONIAL SEABIRDS AT CAPE THOMPSON AND CAPE LISBURNE, ALASKA Principal Investigators Alan M. Springer David G. Roseneau Renewable Resources Consulting Services, Ltd. 3529 College Road Fairbanks, Alaska 99701 839 i CONTENTS I. Summary of objectives, conclusions and implications with respect to OCS oil and gas development 1 II. Introduction -> A. General nature and scope of study 3 B. Specific objectives 3 c. Relevance to problems of petroleum development 3 III. Current state of knowledge 9 Iv. Study area 9 v. Sources, methods and rationale of data collection A. Census 16 B. Phenology of breedirrgacttvities 18 c. Food habits 18 VI. Results A. Murres 19 B. Black-legged Kittiwakes 66 c. Horned Puffins 84 D. Glaucous Gulls 89 E. Pelagic Cormorants 94 F. Tufted Puffins 94 G. Guillemots 96 H. Raptors and Ravens 98 I. Cape Lewis 99 J. Other areas utilized by seabirds 101 K. Other observations 104 840 ii VII and VIII. Discussion and Conclusions 105 Ix. Summary of 4th quarter operations 111 x. Acknowledgements 113 XI. Literature cited 114 841 LIST OF TABLES TABLE PAGE 1. Murre census summary, Cape Thompson. 19 2. Murre census, Colony 1; Cape Thompson, 1977. 20 3. Murre census, Colony 2; Cape Thompson, 1977. 21 4. Murre census, Colony 3; Cape Thompson, 1977, 22 5. Murre census, Colony 4; Cape Thompson, 1977. 23 6. Murre census, Colony 5; Cape Thompson, 1977. 24 7. Score totals, Colonies 1-4. 25 8. Compensation counts of murres; Cape Thompson, 1977. -

Val Emmich ‘Slows It Down’ Upcoming Musician Is Emo’S Latest Voice of Rock Page 5 January 3, 2 0 0 5What’S Inside

MUSIC: ‘The Game’ revives west coast hip-hop MOVIE: Extreme DVD Full proves pain is universal FASHION: What to wear when you can’t find a thing in your closet EFFECTTitan Entertainment Guide The Hives shake things up at the House of Blues Val Emmich ‘slows it down’ Upcoming musician is emo’s latest voice of rock Page 5 January 3, 2 0 0 5What’S Inside Dave Muscato, an Apple fan, has opened www.freefi ona.com in an Contents attempt to make Sony release the album … 50 Cent has dropped the 02 News Briefs “Saint Valentineʼs Day” from his Calendar album title and is simply calling his sophomore effort “The Mas- 03 Movies- Are We There Yet sacre.” A video for the albumʼs Slammed second single “Candy Shop” will Flashback favorite-After be hitting the airwaves this week and the album will drop in March. School Specials Fans of System of a Down have 04 Music- The Hives two reasons to be thankful in 2005. The band will release “Hypno- Lassie Foundation tize,” featuring the single “Ciga- 05 The Game ro,” in late April and a second disc Columbia Pictures called “Mesmerize” in the sum- Val Emmich mer…Alex Garland who penned 06 Food-Brooklyn Pizza Works News Briefs of “How to Dismantle an Atomic “28 Days Later” has been tapped Book- He’s not that into you Bomb. to write “Saw 2” which will make 07 Fashion- Style Scout Head of The Inc., Irv Gotti Trent Reznor of Nine Inch itʼs way to theaters in late Octo- and his brother Chris, have been Nails announced that the bandʼs ber…Peter Jacksonʼs remake of charged with laundering more long awaited album, “With Teeth”, “King Kong,” which starts Naomi than $1 million in drug money which features drumming from Watts and Jack Black, has resumed through the record label. -

Unalaska Hazard Mitigation Plan 2018

Unalaska, Alaska Multi-Jurisdictional Hazard Mitigation Plan Update April 2018 Prepared for: City of Unalaska and Qawalangin Tribe of Unalaska City of Unalaska Hazard Mitigation Plan THIS PAGE LEFT BLANK INTENTIONALLY ii City of Unalaska Hazard Mitigation Plan Table of Contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Hazard Mitigation Planning ..................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Grant Programs with Mitigation Plan Requirements ............................... 1-1 1.2.1 HMA Unified Programs ............................................................... 1-2 2. Community Description ....................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 Location, Geography, and History ........................................................... 2-1 2.2 Demographics .......................................................................................... 2-3 2.3 Economy .................................................................................................. 2-4 3. Planning Process .................................................................................................. 3-1 3.1 Planning Process Overview ..................................................................... 3-1 3.2 Hazard Mitigation Planning Team ........................................................... 3-3 3.3 Public Involvement & Opportunities for Interested Parties to participate ................................................................................................ -

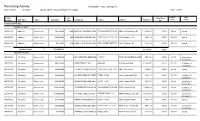

Permitting Activity 01/01/2018 Thru 10/14/2018 Date of Report: 10/15/2018 L-BUILD ONLY - Grouped by Type Then Subtype Page 1 of 295

Permitting Activity 01/01/2018 Thru 10/14/2018 Date of Report: 10/15/2018 L-BUILD ONLY - Grouped by Type then Subtype Page 1 of 295 Issued App. Permit Sq- Total Fees Date Status Number Sub Type Type Valuation Feet Contractor Owner Address Total Fees Due Commercial Permits: Addition Permits: LB1701130 Addition Commercial $92,900.00 1300 HAGGAI CONSTRUCTION &ST DEVELOPMENT PAULS BAPTIST INC CHURCH8002 Old Bainbridge Rd $1,803.31 $0.00 1/3/18 Issued LB1800208 Addition Commercial $20,000.00 400 GARRISON DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION,GARRISON DESIGN INC. & CONTRUCTION5186 Woodlane Cir $481.13 $0.00 5/22/18 Issued LB1801519 Addition Commercial $5,500.00 240 TONY E. COLVIN INC DBA SOUTHERNNEW JOURNEY FIXIN'S BAPTIST CHURCH4527 N Monroe St $135.40 $0.00 10/4/18 Issued Addition Totals: 3 $118,400.00 $2,419.84 $0.00 Alteration Permits: LB1602042 Alteration Commercial $22,000.00 SBA NETWORK SERVICES LLCT-MOBILE 5585 CRAWFORDVILLE RD $603.86 $0.00 2/2/18 Certificate of Completion LB1700443 Alteration Commercial $56,000.00 SIMPLERBUILT, INC. SABL LLC 5205 Mcneill Blvd $1,868.57 $0.00 3/12/18 Certificate of Completion LB1701599 Alteration Commercial $20,000.00 ATLANTIC TOWER SERVICES,LANG INC MARY ALMA TRUST 6017 Roberts Rd $648.41 $0.00 4/5/18 Issued LB1701639 Alteration Commercial $20,000.00 ASCEND WIRELESS NETWORKS,TYRE JANICE INC. L 5585 Crawfordville Rd $481.73 $0.00 1/18/18 Certificate of Completion LB1701744 Alteration Commercial $20,000.00 ASCEND WIRELESS NETWORKS,MOOSE INC. LODGE 1484 Capital Cir NW $621.56 $0.00 4/3/18 Certificate of Completion LB1701795 Alteration Commercial $228,920.00 LEDFORD DESIGN & CONSTRUCTION,FLEA MARKET LLC.