The Mcdonaldization of Multimedia Journalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethics for Digital Journalists

ETHICS FOR DIGITAL JOURNALISTS The rapid growth of online media has led to new complications in journalism ethics and practice. While traditional ethical principles may not fundamentally change when information is disseminated online, applying them across platforms has become more challenging as new kinds of interactions develop between jour- nalists and audiences. In Ethics for Digital Journalists , Lawrie Zion and David Craig draw together the international expertise and experience of journalists and scholars who have all been part of the process of shaping best practices in digital journalism. Drawing on contemporary events and controversies like the Boston Marathon bombing and the Arab Spring, the authors examine emerging best practices in everything from transparency and verifi cation to aggregation, collaboration, live blogging, tweet- ing, and the challenges of digital narratives. At a time when questions of ethics and practice are challenged and subject to intense debate, this book is designed to provide students and practitioners with the insights and skills to realize their potential as professionals. Lawrie Zion is an Associate Professor of Journalism at La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia, and editor-in-chief of the online magazine upstart. He has worked as a broadcaster with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and as a fi lm journalist for a range of print publications. He wrote and researched the 2007 documentary The Sounds of Aus , which tells the story of the Australian accent. David Craig is a Professor of Journalism and Associate Dean at the University of Oklahoma in the United States. A former newspaper copy editor, he is the author of Excellence in Online Journalism: Exploring Current Practices in an Evolving Environ- ment and The Ethics of the Story: Using Narrative Techniques Responsibly in Journalism . -

A Decade of the Knight News Challenge: Investing in Innovators to Advance News, Media, and Information

A DECADE OF THE KNIGHT NEWS CHALLENGE: INVESTING IN INNOVATORS TO ADVANCE NEWS, MEDIA, AND INFORMATION PRESENTED TO November 2017 1 / 31 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION AND MAJOR FINDINGS 3 OVERVIEW OF KNIGHT NEWS CHALLENGE WINNERS 6 KNIGHT NEWS CHALLENGE IMPACT ON WINNERS 16 FIELD IMPACT 21 CONCLUSION 26 APPENDIX A 28 SELECTED WINNER CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE FIELD APPENDIX B 30 METHODOLOGY INTRODUCTION AND MAJOR FINDINGS Over the last two decades, technology has transformed the way consumers interact with news and media, including how they create, consume, and share information. These advances have challenged traditional media organizations to adapt the way they deliver content to stay relevant to readers, fulfill their missions, and sustain their work. In 2006, the Knight Foundation launched the Knight News Challenge (KNC) to invest in new ideas and individuals to support innovation in news and information. Since its launch, the KNC has provided more than $48 million to fund 139 projects in the United States and around the world. 3 / 31 To better understand how the Challenge impacted winners1 , their projects, and the broader fields of news, media, and journalism, Arabella Advisors conducted a retrospective evaluation of the last 10 years of the KNC (2006– 2016)2. Through this research, we identified ways the Challenge has impacted the field and its winners, including: Enabling and Advancing Innovators in Journalism and the Media The KNC helped to support a group of individuals and organizations working at the nexus of technology and journalism and, in large part, has kept those individuals within the media field. Of all winners, 84 percent remain in the fields of journalism, technology and, media. -

The Mcdonaldization of Medicine

Opinion VIEWPOINT The McDonaldization of Medicine E. Ray Dorsey, MD, AsputforthinTheMcDonaldizationofSociety,“theprin- length of patient visits can result in equal care that does MBA ciples of the fast-food restaurant are coming to domi- not address individual needs. Department of nate more and more sectors of American society,”1 The final dimension of McDonaldization is control Neurology, University including medicine (Table). While designed to produce of humans by nonhuman technology,1 which is increas- of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, a rational system, the 4 basic principles of McDonaldiza- ingly applied to both physicians and patients. In fast- New York. tion—efficiency,calculability,predictability,and control— food restaurants, machines, not workers, control cook- often lead to adverse consequences. Without mea- ing. In medicine, resident physicians now spend far more George Ritzer, PhD, sures to counter McDonaldization, medicine’s most time with computers (40%) than with patients (12%).4 MBA cherished and defining values including care for the Billing codes and policies, which specify the length and Department of Sociology, University of individual and meaningful patient-physician relation- content of visits, dictate the care that patients receive, Maryland, College Park. ships will be threatened. influence clinicians, lead to unnecessary procedures, and McDonaldization’sfirstdimensionisefficiency,orthe can adversely affect patient health. The electronic medi- effort to find the optimal means to any end. While cal record controls interactions between physicians and efficiency is “generally a good thing,”1 irrationalities patients by specifying what questions must be asked and develop in the march toward ever-increasing efficiency. what tasks must be completed, thereby substituting the For example, while the drive-through window is effi- judgment of a computer for that of a physician. -

The State of Multimedia Newsrooms in Europe

MIT 2002 The State of Multimedia Newsrooms in Europe Martha Stone, Jan Bierhoff Introduction The media landscape worldwide is changing rapidly. In the 1980s, the “traditional” mass media players were in control: TV, newspapers and radio. Newspaper readers consumed the paper at a specified time of the day, in the morning, over breakfast or after work. Radio was listened to on the way to and from work. Television news was watched in the morning mid-day and/or evening. Fast forward to 2002, and the media landscape is fragmented. The consumption of news has changed dramatically. News information is all around, on mobile phones, newspapers, PDAs, TV, Interactive TV, cable, Internet, teletext, kiosks, radio, video screens in hotel elevators, video programming for airlines and much more. Meanwhile, also the concept of news has changed to be more personalised, more service-oriented and less institutional. The sweeping market changes have forced media companies to adapt. This new challenge explains why Dow Jones Company, owner of the Wall Street Journal, now considers itself “a news provider of any news, all the time, everywhere.” In the frame of the MUDIA project (see annex 1), an international team of researchers has taken stock of the present situation concerning media and newsroom convergence in Europe. The various routes taken to this ideal have been mapped in a number of case studies. In total 24 leading European media (newspapers, broadcasters, netnative newscasters) were approached with a comprehensive questionnaire and later visited to interview key representatives of the editorial and commercial departments (see annex 2). The study zoomed in on four countries: the United Kingdom, Spain, France and Sweden; viewpoints from other media elsewhere in Europe were added on the basis of existing literature, and throughout the study a comparison with the USA is made where possible and relevant. -

Spring 2019 Umass Journalism Courses Confirm Classes, Time and Location on SPIRE

Spring 2019 UMass Journalism Courses Confirm classes, time and location on SPIRE. This is a guide, and courses may change. Journal 201: Introduction to Journalism (4 cr.) Cap. 100 Open to first-year and sophomores of any major. Gen Ed: SB DU TTH 8:30 a.m. - 9:45 a.m. Sibii ILC S140 Introduction to Journalism is a survey class that covers the basic principles and practices of contemporary journalism. By studying fundamentals like truth telling, fact checking, the First Amendment, diversity, being a watchdog to the powerful and public engagement, students will explore the best of what journalists do in a democratic society. Students will also assess changes in the production, distribution, and consumption of journalism as new technologies are introduced to newsrooms. Toward the end of the semester, students look at case studies across the media and learn how different audiences, mediums, and perspectives affect the news. Journal 250: News Literacy (4 cr.) Cap. 40 Open to any major. Gen Ed: SB TTh 10:00 a.m. - 11:15 a.m. Fox ILC N255 What is fact? What is fiction? Can we even tell the difference anymore? Today’s 24-hour news environment is saturated with a wide array of sources ranging from real-time citizen journalism reports, government propaganda and corporate spin to real-time blogging, photos, and videos from around the world, as well as reports from the mainstream media. In this class, students will become more discerning consumers of news. Students will use critical-thinking skills to develop the tools needed to determine what news sources are reliable in the digital world. -

SCIENCE and the MEDIA AMERICAN ACADEMY of ARTS & SCIENCES Science and the Media

SCIENCE AND THE MEDIA AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ARTS & SCIENCES SCIENCE AND THE MEDIA AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ARTS Science and the Media Edited by Donald Kennedy and Geneva Overholser AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ARTS & SCIENCES AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ARTS & SCIENCES Science and the Media Please direct inquiries to: American Academy of Arts and Sciences 136 Irving Street Cambridge, MA 02138-1996 Telephone: 617-576-5000 Fax: 617-576-5050 Email: [email protected] Web: www.amacad.org Science and the Media Edited by Donald Kennedy and Geneva Overholser © 2010 by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences All rights reserved. ISBN#: 0-87724-087-6 The American Academy of Arts and Sciences is grateful to the Annenberg Foundation Trust at Sunnylands for supporting The Media in Society project. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Annenberg Foundation Trust at Sunnylands or the Officers and Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Contents vi Acknowledgments vii Preface 1 Chapter 1 Science and the Media Donald Kennedy 10 Chapter 2 In Your Own Voice Alan Alda 13 Chapter 3 Covering Controversial Science: Improving Reporting on Science and Public Policy Cristine Russell 44 Chapter 4 Civic Scientific Literacy: The Role of the Media in the Electronic Era Jon D. Miller 64 Chapter 5 Managing the Trust Portfolio: Science Public Relations and Social Responsibility Rick E. Borchelt, Lynne T. Friedmann, and Earle Holland 71 Chapter 6 Response to Borchelt, Friedmann, and Holland on Managing the Trust Portfolio: Science Public Relations and Social Responsibility Robert Bazell 74 Chapter 7 The Scientist as Citizen Cornelia Dean 80 Chapter 8 Revitalizing Science Journalism for a Digital Age Alfred Hermida 88 Chapter 9 Responsible Reporting in a Technological Democracy William A. -

An Introduction to Mcdonaldization

Ritzer-ch01.qxd 1/22/02 11:05 AM Page 7 1 An Introduction to McDonaldization George Ritzer cDonald’s is the basis of one of the most influential developments in Mcontemporary society. Its reverberations extend far beyond its point of origin in the United States and in the fast-food business. It has influenced a wide range of undertakings, indeed the way of life, of a significant portion of the world. And that impact is likely to expand at an accelerating rate. However, this is not . about McDonald’s, or even about the fast-food business. Rather, McDonald’s serves here as the major example, the paradigm, of a wide-ranging process I call McDonaldization—that is, the process by which the principles of the fast-food restaurant are coming to dominate more and more sectors of American society as well as of the rest of the world. As you will see, McDonaldization affects not only the restaurant business but also . virtually every other aspect of society. McDonaldization has shown every sign of being an inexorable process, sweeping through seem- ingly impervious institutions and regions of the world. Editor’s Note: Excerpts from “An Introduction to McDonaldization,” pp. 1–19 in The McDonaldization of Society, 3rd ed., by George Ritzer. Copyright © 2000, Pine Forge Press, Thousand Oaks, CA. Used with permission. 7 Ritzer-ch01.qxd 1/22/02 11:05 AM Page 8 8 Basics, Studies, Applications, and Extensions The success of McDonald’s itself is apparent. “There are McDonald’s everywhere. There’s one near you, and there’s one being built right now even nearer to you. -

Efficiency and Calculability

3 Efficiency and Calculability Consumers 1 distribute or hapter 2 dealt largely with the organizations and systems that have been C the precursors of the process of McDonaldization. As we saw, they include bureaucracies, concentration camps, industrial organizations, suburban communities, shopping centers, and, of course, fast-food restaurants. Needless to say, people exist in these settings.post, It is the norm to distinguish between two types of people in these settings: consumers (or customers, clients) and produc- ers (or workers). We will adhere to that norm in the next four chapters. This chapter and the next will deal with consumers, while Chapters 5 and 6 will be devoted to producers. However, more and more scholars are rejecting the binary distinction betweencopy, producers and consumers and thinking more in terms of “prosumers,” or those who both produce and consume.1 We will have more to say about prosumers at several points in this book, but for the time being we will set that concept aside and deal separately with consumers and producers.not This chapter deals with consumers in terms of two of the four basic dimen- sions of McDonaldization: efficiency and calculability. Chapter 4 does the same withDo the other two dimensions of McDonaldization: predictability and control. While the focus is on the consumer, workers—the producers—will inevitably be touched on in these chapters and discussions. We will deal with a wide array of consumers in the next two chapters includ- ing tourists, students, campers, diners, patients, parents, mothers-to-be, shop- pers (including cybershoppers), dieters, exercisers, and those looking for dates (or for only sex). -

Graduate Journalism Course Descriptions

Graduate Journalism Course Description Handbook Table of Contents JOUR 500 Introduction to Newswriting and English-Language Reporting 3 JOUR 503 Visual Literacy and Introduction to Documentary Storytelling 3 JOUR 504 Introduction to Emerging Technology 3 JOUR 505 The Practice: Journalism’s Evolution as a Profession 4 JOUR 508 Introduction to Video Reporting 4 JOUR 510 Special Assignment Reporting 4 JOUR 511 Introduction to Narrative Non-Fiction 4 JOUR 512 Advanced Interpretive Writing 4 JOUR 515 Introduction to Audio Storytelling 4 JOUR 517 Advanced Investigative Reporting 5 JOUR 519 Advanced Writing and Reporting for Magazine and the Web 5 JOUR 521 Documentary Pre-Production 5 JOUR 522 Video Documentary Production 6 JOUR 523 Public Radio Reporting 6 JOUR 524 Advanced Broadcast Reporting 6 JOUR 525 This California Life: Storytelling for Radio and Podcasting 6 JOUR 526 Advanced Broadcast News Production 6 JOUR 527 Advanced Disruption: Innovation with Emerging Technology 6 JOUR 528 Summer Digital News Immersion 6 JOUR 531 Fall Digital News Immersion 7 JOUR 533 Web Journalism and Editorial Site Management 7 JOUR 539 Introduction to Investigative Reporting 7 JOUR 540 International Journalism Seminar I 7 JOUR 542 Foreign Affairs Reporting 7 JOUR 545 International Internships in the Media 7 JOUR 546 News, Numbers and Introduction to Data Journalism 7 JOUR 547 Navigating the Media Marketplace 8 JOUR 552 Television Reporting and Production 8 JOUR 553 Coding and Programming for Storytelling 8 JOUR 554 Reporting with Data 8 JOUR 555 Advanced Coding -

The Mcdonaldization of Academic Libraries?

248 College & Research Libraries May 2000 The McDonaldization of Academic Libraries? Brian Quinn George Ritzer, a sociologist at the University of Maryland, has proposed an influential thesis that suggests that many aspects of the fast food industry are making their way into other areas of society. This article explores whether his thesis, known as the McDonaldization thesis, is applicable to academic libraries. Specifically, it seeks to determine to what extent academic libraries may be considered McDonaldized, and if so, what effect McDonaldization may be having on them. It also investi gates some possible alternatives to McDonaldization, and their implica tions for academic libraries. n 1993, George Ritzer, a soci chy of functionaries performing nar ologist at the University of rowly defined roles according to pre Maryland, wrote a book titled scribed rules.3 Weber was careful to point The McDonaldization of Society.1 out that although rationalized social in It caused considerable controversy in the stitutions such as bureaucracies had the field of sociology and in academia gener advantage of being efficient, if carried to ally, sold many copies, and inspired sev extremes, they could lead to their own eral articles and even a book to be writ form of irrationality, which he termed an ten about the subject.2 In his book, Ritzer “iron cage.” The iron cage metaphor re argued that the principles of the fast-food ferred to Weber’s belief that extremely industry had gradually come to pervade rationalized institutions could be dehu other areas of society. manizing and stultifying to both those In The McDonaldization of Society, who work in them and those they serve. -

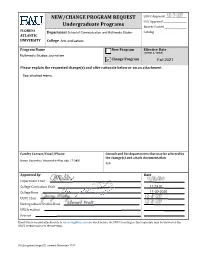

NEW/CHANGE PROGRAM REQUEST Undergraduate Programs

NEW/CHANGE PROGRAM REQUEST UUPC Approval _________________ UFS Approval ___________________ Undergraduate Programs Banner Posted __________________ FLORIDA Department School of Communication and Multimedia Studies Catalog __________________________ ATLANTIC UNIVERSITY College Arts and Letters Program Name New Program Effective Date (TERM & YEAR) Multimedia Studies Journalism ✔ Change Program Fall 2021 Please explain the requested change(s) and offer rationale below or on an attachment See attached memo. Faculty Contact/Email/Phone Consult and list departments that may be affected by the change(s) and attach documentation Aaron Veenstra / [email protected] / 7-3851 N/A Approved by Date Department Chair College Curriculum Chair 11.23.20 College Dean 11-30-2020 UUPC Chair Undergraduate Studies Dean UFS President Provost Email this form and attachments to [email protected] one week before the UUPC meeting so that materials may be viewed on the UUPC website prior to the meeting. FAUprogramchangeUG, created December 2017 Memo for Multimedia Journalism Program Changes: 1. In an effort the streamline the curriculum, decrease time to degree, and maintain curricular rigor, the MMSJ program proposes several changes. We will reduce the required number of credits from 50 credits to a minimum of 38 (can be more depending on focus courses selected). 2. We are also dividing the MMSJ Curriculum into three parallel streams: Core (13 required credits), Production (13 required credits), Focus (12 required credits minimum). This entails renaming: a. the “Disciplinary Core” into “Core,” b. renaming the “Performance and Production” category to “Production” and, c. remove/collapse all remaining current sections, Focus, Theory/History/Criticism, and Performance and Production Emphasis”, to “Focus” resulting the categories as listed below: Core The following courses are required (13 credits): MMC 1540 Introduction to Multimedia Studies (3 credits) JOU 4004 U.S. -

University of Calicut Board of Studies (Ug) In

[Type text] UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT BOARD OF STUDIES (UG) IN JOURNALISM Restructured Curriculum and Syllabi as per CBCSSUG Regulations 2019 (2019 Admission Onwards) PART I B.A. Journalism and Mass Communication PART II Complementary Courses in 1. Journalism, 2. Electronic Media 3. Mass Communication (for BA West Asian Studies) 4. Complementary Courses in Media Practices for B.A LRP Programmes in Visual Communication, Multimedia, and Film and Television for Non-Journalism UG Programmes [Type text] GENERAL SCHEME OF THE PROGRAMME Sl No Course No of Courses Credits 1 Common Courses (English) 6 22 2 Common Courses (Additional Language) 4 16 3 Core Courses 15 61 4 Project (Linked to Core Courses) 1 2 5 Complementary Courses 2 16 6 Open Courses 1 3 Total 120 Audit course 4 16 Extra Credit Course 1 4 Total 140 [Type text] PART I B.A. JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION Distribution of Courses A - Common Courses B - Core Courses C - Complementary Courses D - Open Courses Ability Enhancement Course/Audit Course Extra Credit Activities [Type text] A. Common Courses Sl. No. Code Title Semester 1 A01 Common English Course I I 2 A02 Common English Course II I 3 A03 Common English Course III II 4 A04 Common English Course IV II 5 A05 Common English Course V III 6 A06 Common English Course VI IV 7 A07 Additional language Course I I 8 A08 Additional language Course II II 9 A09 Additional language Course III III 10 A10 Additional language Course IV IV Total Credit 38 [Type text] B. Core Courses Sl. No. Code Title Contact hrs Credit Semester 11 JOU1B01 Fundamentals