UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Cubans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Areas and Periods of Culture in the Greater Antilles Irving Rouse

AREAS AND PERIODS OF CULTURE IN THE GREATER ANTILLES IRVING ROUSE IN PREHISTORIC TIME, the Greater Antilles were culturally distinct, differingnot only from Florida to the north and Yucatan to the west but also, less markedly,from the Lesser Antilles to the east and south (Fig. 1).1 Within this major provinceof culture,it has been customaryto treat each island or group FIG.1. Map of the Caribbeanarea. of islands as a separatearchaeological area, on the assumptionthat each contains its own variant of the Greater Antillean pattern of culture. J. Walter Fewkes proposedsuch an approachin 19152 and worked it out seven years later.3 It has since been adopted, in the case of specific islands, by Harrington,4Rainey,5 and the writer.6 1 Fewkes, 1922, p. 59. 2 Fewkes, 1915, pp. 442-443. 3 Fewkes, 1922, pp. 166-258. 4 Harrington, 1921. 5 Rainey, 1940. 6 Rouse, 1939, 1941. 248 VOL. 7, 1951 CULTURE IN THE GREATERANTILLES 249 Recent work in connectionwith the CaribbeanAnthropological Program of Yale University indicates that this approach is too limited. As the distinction between the two major groups of Indians in the Greater Antilles-the Ciboney and Arawak-has sharpened, it has become apparent that the areas of their respectivecultures differ fundamentally,with only the Ciboney areas correspond- ing to Fewkes'conception of distributionby islands.The Arawak areascut across the islands instead of enclosing them and, moreover,are sharply distinct during only the second of the three periods of Arawak occupation.It is the purpose of the presentarticle to illustratethese points and to suggest explanationsfor them. -

Artist's Work Lets Cubans Speak out in Havana for Freedom

Artist's work lets Cubans speak out in Havana for freedom By FABIOLA SANTIAGO A packed performance art show at the 10th Havana Biennial, a prestigious international festival, turned into a clamor of ''Libertad!'' as Cubans and others took to a podium to protest the lack of freedom of expression on the island. The provocative performance Sunday night, recorded and posted Monday on YouTube, was staged by acclaimed Cuban artist Tania Bruguera, a frequent visitor to Art Basel Miami Beach who lives in Havana. Bruguera set up a podium with a microphone in front of a red curtain at the Wifredo Lam Center, an official art exhibition space and biennial venue. Two actors clad in the military fatigue uniforms of the Ministry of the Interior, the agency charged with spying on Cubans' activities, flanked the podium and carried a white dove. Bruguera let people from the standing-room only audience come to the microphone for no more than one minute. As people spoke, the white dove was placed on their shoulders by the actors. ''Let's stop waiting for permission to use the Internet,'' urged Yoani Sánchez, who has written a controversial award-winning ''Generación Y'' blog chronicling Cuban life under constant threats from the government. ''Libertad! Libertad!'' shouted one man. ''Too many years of covering the sun with one finger,'' said another. To every call for freedom, the audience responded with shouts of ``Bravo!'' The performance appeared to mock a historic Jan. 8, 1959, victory speech by Fidel Castro at which a white dove landed on his shoulder, viewed by many as a sign of divine recognition. -

Latino Louisiana Laź Aro Lima University of Richmond, [email protected]

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Latin American, Latino and Iberian Studies Faculty Latin American, Latino and Iberian Studies Publications 2008 Latino Louisiana Laź aro Lima University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/lalis-faculty-publications Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the Latin American Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Lima, Lazá ro. "Latino Louisiana." In Latino America: A State-by-State Encyclopedia, Volume 1: Alabama-Missouri, edited by Mark Overmyer-Velázquez, 347-61. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, LLC., 2008. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Latin American, Latino and Iberian Studies at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Latin American, Latino and Iberian Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 19 LOUISIANA Lazaro Lima CHRONOLOGY 1814 After the British invade Louisiana, residents of the state from the Canary Islands, called Islenos, organize and establish three regiments. The Is/enos had very few weapons, and some served unarmed as the state provided no firearms. By the time the British were defeated, the Islenos had sustained the brunt of life and property loss resulting from the British invasion of Louisiana. 1838 The first. Mardi Gras parade takes place in New Orleans on Shrove Tuesday with the help and participation of native-born Latin Americans and Islenos. 1840s The Spanish-language press in New Orleans supersedes the state's French-language press in reach and distribution. 1846-1848 Louisiana-born Eusebio Juan Gomez, editor of the eminent Spanish language press newspaper La Patria, is nominated as General Winfield Scott's field interpreter during the Mexican-American War. -

The Spanish- American War

346-351-Chapter 10 10/21/02 5:10 PM Page 346 The Spanish- American War MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW Terms & Names In 1898, the United States U.S. involvement in Latin •José Martí •George Dewey went to war to help Cuba win America and Asia increased •Valeriano Weyler •Rough Riders its independence from Spain. greatly as a result of the war •yellow journalism •San Juan Hill and continues today. •U.S.S. Maine •Treaty of Paris One American's Story Early in 1896, James Creelman traveled to Cuba as a New York World reporter, covering the second Cuban war for independ- ence from Spain. While in Havana, he wrote columns about his observations of the war. His descriptions of Spanish atrocities aroused American sympathy for Cubans. A PERSONAL VOICE JAMES CREELMAN “ No man’s life, no man’s property is safe [in Cuba]. American citizens are imprisoned or slain without cause. American prop- erty is destroyed on all sides. Wounded soldiers can be found begging in the streets of Havana. The horrors of a barbarous struggle for the extermination of the native popula- tion are witnessed in all parts of the country. Blood on the roadsides, blood in the fields, blood on the doorsteps, blood, blood, blood! . Is there no nation wise enough, brave enough to aid this blood-smitten land?” —New York World, May 17, 1896 Newspapers during that period often exaggerated stories like Creelman’s to boost their sales as well as to provoke American intervention in Cuba. M Cuban rebels burn the town of Jaruco Cubans Rebel Against Spain in March 1896. -

African-Americans and Cuba in the Time(S) of Race Lisa Brock Art Institute of Chicago

Contributions in Black Studies A Journal of African and Afro-American Studies Volume 12 Ethnicity, Gender, Culture, & Cuba Article 3 (Special Section) 1994 Back to the Future: African-Americans and Cuba in the Time(s) of Race Lisa Brock Art Institute of Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cibs Recommended Citation Brock, Lisa (1994) "Back to the Future: African-Americans and Cuba in the Time(s) of Race," Contributions in Black Studies: Vol. 12 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cibs/vol12/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Afro-American Studies at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Contributions in Black Studies by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Brock: Back to the Future Lisa Brock BACK TO THE FUTURE: AFRICAN AMERICANS AND CUBA IN THE TIME(S) OF RACE* UBA HAS, AT LEAST SINCE the American revolution, occupied the imagination of North Americans. For nineteenth-century capital, Cuba's close proximity, its C Black slaves, and its warm but diverse climate invited economic penetration. By 1900, capital desired in Cuba "a docile working class, a passive peasantry, a compliant bourgeoisie, and a subservient political elite.'" Not surprisingly, Cuba's African heritage stirred an opposite imagination amongBlacksto the North. The island's rebellious captives, its anti-colonial struggle, and its resistance to U.S. hegemony beckoned solidarity. Like Haiti, Ethiopia, and South Africa, Cuba occupied a special place in the hearts and minds of African-Americans. -

The Cuban Refugee Program by WILLIAM 1

The Cuban Refugee Program by WILLIAM 1. MITCHELL* FOR the first time in its hist,ory t,he United the President.‘s Contingency Fund under the Sbates has become a country of first asylum for Mutual Security Act a.nd partly, at first, from large numbers of displaced persons as thousands private funds. In his fin,al report,, Mr. Voorhe.es of Cuban refugees have found political refuge reported that the refugee problem had assumed here. For the first t,ime, also, the United States proportions requiring national attention and made Government. has found it necessary to develop a several recommendations aimed at its solution. program to help refugees from another nation in this hemisphere. The principal port of entry for these refugees ESTABLISHING THE PROGRAM has been, and is, Miami, and most of them remain Secretary Ribicoff’s report t,o President Ken- in t.he Miami area. Many of t,he refugees quickly nedy reemphasized the need for a comprehensive exhaust any personal resources they may have. program of aid, and on February 3 the President The economic and social problems that they face directed the Secretary to take the following a.nd that they pose for Miami and for all of actions : southern Florida are obvious. State and local 1. Provide all possible assistance to voluntary official and volunt,ary welfare agencies in the area relief agencies in providing d&y necessities for have struggled valiantly with these problems- many of the refugees, for resettling as many of problems of shelter, of food, of employment, of them as possible, and for securing jobs for them. -

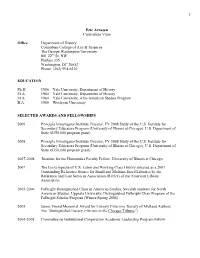

Arnesen CV GWU Website June 2009

1 Eric Arnesen Curriculum Vitae Office Department of History Columbian College of Arts & Sciences The George Washington University 801 22nd St. NW Phillips 335 Washington, DC 20052 Phone: (202) 994-6230 EDUCATION Ph.D. 1986 Yale University, Department of History M.A. 1984 Yale University, Department of History M.A. 1984 Yale University, Afro-American Studies Program B.A. 1980 Wesleyan University SELECTED AWARDS AND FELLOWSHIPS 2009 Principle Investigator/Institute Director, FY 2008 Study of the U.S. Institute for Secondary Educators Program (University of Illinois at Chicago), U.S. Department of State ($350,000 program grant) 2008 Principle Investigator/Institute Director, FY 2008 Study of the U.S. Institute for Secondary Educators Program (University of Illinois at Chicago), U.S. Department of State ($350,000 program grant) 2007-2008 Institute for the Humanities Faculty Fellow, University of Illinois at Chicago 2007 The Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working Class History selected as a 2007 Outstanding Reference Source for Small and Medium-Sized Libraries by the Reference and User Services Association (RUSA) of the American Library Association. 2005-2006 Fulbright Distinguished Chair in American Studies, Swedish Institute for North American Studies, Uppsala University, Distinguished Fulbright Chair Program of the Fulbright Scholar Program (Winter-Spring 2006) 2005 James Friend Memorial Award for Literary Criticism, Society of Midland Authors (for “distinguished literary criticism in the Chicago Tribune”) 2004-2005 Committee on Institutional -

Ever Faithful

Ever Faithful Ever Faithful Race, Loyalty, and the Ends of Empire in Spanish Cuba David Sartorius Duke University Press • Durham and London • 2013 © 2013 Duke University Press. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ∞ Tyeset in Minion Pro by Westchester Publishing Services. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Sartorius, David A. Ever faithful : race, loyalty, and the ends of empire in Spanish Cuba / David Sartorius. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 8223- 5579- 3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978- 0- 8223- 5593- 9 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Blacks— Race identity— Cuba—History—19th century. 2. Cuba— Race relations— History—19th century. 3. Spain— Colonies—America— Administration—History—19th century. I. Title. F1789.N3S27 2013 305.80097291—dc23 2013025534 contents Preface • vii A c k n o w l e d g m e n t s • xv Introduction A Faithful Account of Colonial Racial Politics • 1 one Belonging to an Empire • 21 Race and Rights two Suspicious Affi nities • 52 Loyal Subjectivity and the Paternalist Public three Th e Will to Freedom • 94 Spanish Allegiances in the Ten Years’ War four Publicizing Loyalty • 128 Race and the Post- Zanjón Public Sphere five “Long Live Spain! Death to Autonomy!” • 158 Liberalism and Slave Emancipation six Th e Price of Integrity • 187 Limited Loyalties in Revolution Conclusion Subject Citizens and the Tragedy of Loyalty • 217 Notes • 227 Bibliography • 271 Index • 305 preface To visit the Palace of the Captain General on Havana’s Plaza de Armas today is to witness the most prominent stone- and mortar monument to the endur- ing history of Spanish colonial rule in Cuba. -

[email protected] E-ISSN 2300-6250 the Electronic Version of Crossroads

ISSUE 25 2/2019 An electronic journal published by The University of Bialystok ISSUE 25 2/2019 An electronic journal published by The University of Bialystok .................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Publisher: The University of Bialystok The Faculty of Philology Department of English ul. Liniarskiego 3 15-420 Białystok, Poland tel. 0048 85 7457516 [email protected] www.crossroads.uwb.edu.pl e-ISSN 2300-6250 The electronic version of Crossroads. A Journal of English Studies is its primary (referential) version. Editor-in-chief: Agata Rozumko Literary editor: Grzegorz Moroz Editorial Board: Sylwia Borowska-Szerszun, Jerzy Kamionowski, Daniel Karczewski, Weronika Łaszkiewicz, Jacek Partyka, Daniela Francesca Virdis, Beata Piecychna, Tomasz Sawczuk Editorial Assistant: Ewelina Feldman-Kołodziejuk Language editors: Kirk Palmer, Peter Foulds Advisory Board: Pirjo Ahokas (University of Turku), Lucyna Aleksandrowicz-Pędich (SWPS: University of Social Sciences and Humanities), Ali Almanna (Sohar University), Isabella Buniyatova (Borys Ginchenko Kyiev University), Xinren Chen (Nanjing University), Marianna Chodorowska-Pilch (University of Southern California), Zinaida Charytończyk (Minsk State Linguistic University), Gasparyan Gayane (Yerevan State Linguistic University “Bryusov”), -

Sesiune Speciala Intermediara De Repartitie - August 2018 DACIN SARA Aferenta Difuzarilor Din Perioada 01.04.2008 - 31.03.2009

Sesiune speciala intermediara de repartitie - August 2018 DACIN SARA aferenta difuzarilor din perioada 01.04.2008 - 31.03.2009 TITLU TITLU ORIGINAL AN TARA R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 R6 R7 R8 R9 S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 S9 S10 S11 S12 S13 S14 S15 A1 A2 3:00 a.m. 3 A.M. 2001 US Lee Davis Lee Davis 04:30 04:30 2005 SG Royston Tan Royston Tan Liam Yeo 11:14 11:14 2003 US/CA Greg Marcks Greg Marcks 1941 1941 1979 US Steven Bob Gale Robert Zemeckis (Trecut, prezent, viitor) (Past Present Future) Imperfect Imperfect 2004 GB Roger Thorp Guy de Beaujeu 007: Viitorul e in mainile lui - Roger Bruce Feirstein - 007 si Imperiul zilei de maine Tomorrow Never Dies 1997 GB/US Spottiswoode ALCS 10 produse sau mai putin 10 Items or Less 2006 US Brad Silberling Brad Silberling 10.5 pe scara Richter I - Cutremurul I 10.5 I 2004 US John Lafia Christopher Canaan John Lafia Ronnie Christensen 10.5 pe scara Richter II - Cutremurul II 10.5 II 2004 US John Lafia Christopher Canaan John Lafia Ronnie Christensen 100 milioane i.Hr / Jurassic in L.A. 100 Million BC 2008 US Griff Furst Paul Bales 101 Dalmatians - One Hamilton Luske - Hundred and One Hamilton S. Wolfgang Bill Peet - William 101 dalmatieni Dalmatians 1961 US Clyde Geronimi Luske Reitherman Peed EG/FR/ GB/IR/J Alejandro Claude Marie-Jose 11 povesti pentru 11 P/MX/ Gonzalez Amos Gitai - Lelouch - Danis Tanovic - Alejandro Gonzalez Amos Gitai - Claude Lelouch Danis Tanovic - Sanselme - Paul Laverty - Samira septembrie 11'09''01 - September 11 2002 US Inarritu Mira Nair SACD SACD SACD/ALCS Ken Loach Sean Penn - ALCS -

Race, Nation, and Popular Culture in Cuban New York City and Miami, 1940-1960

Authentic Assertions, Commercial Concessions: Race, Nation, and Popular Culture in Cuban New York City and Miami, 1940-1960 by Christina D. Abreu A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (American Culture) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof Associate Professor Richard Turits Associate Professor Yeidy Rivero Associate Professor Anthony P. Mora © Christina D. Abreu 2012 For my parents. ii Acknowledgments Not a single word of this dissertation would have made it to paper without the support of an incredible community of teachers, mentors, colleagues, and friends at the University of Michigan. I am forever grateful to my dissertation committee: Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof, Richard Turits, Yeidy Rivero, and Anthony Mora. Jesse, your careful and critical reading of my chapters challenged me to think more critically and to write with more precision and clarity. From very early on, you treated me as a peer and have always helped put things – from preliminary exams and research plans to the ups and downs of the job market – in perspective. Your advice and example has made me a better writer and a better historian, and for that I thank you. Richard, your confidence in my work has been a constant source of encouragement. Thank you for helping me to realize that I had something important to say. Yeidy, your willingness to join my dissertation committee before you even arrived on campus says a great deal about your intellectual generosity. ¡Mil Gracias! Anthony, watching you in the classroom and interact with students offered me an opportunity to see a great teacher in action. -

San Francisco Chronicle Jan. 1997 DEAL on ICE by Les Standiford

San Francisco Chronicle Jan. 1997 DEAL ON ICE By Les Standiford HarperCollins; 256 pp. A swelling number of readers insist that in the steamy literary sleazeworld of South Florida that's home to Elmore Leonard, Paul Levine, James Hall, Edna Buchanan and Carl Hiaasen there's no smoother nor more substantial crime novelist than Miami's Les Standiford. In the fourth and most sophisticated of his Deal thrillers, Standiford once again packs maximum mayhem per page into what should be the happy life of John Deal, successful building contractor and accidental sleuth. When we first see Deal this time, he's waking in the wee hours to find a Pat Boone lookalike interviewing a stylish gray-haired man on t.v. "We're moving toward the One World government," says right-wing televangelist James Ray Willis, "the rise of the Global Plantation." Preaching to the marginalized multitudes, Willis cajoles them to his flock by insisting the enemy "international media” makes them feel like failures. To clear his soul, Deal heads to the quality independent bookstore of his old friend Arch Dolan, where years earlier he'd heard Isaac Bashevis Singer and James Baldwin, because "no matter what was wrong with the momentary world, he could walk into Arch's, start wandering the rooms, in a couple of minutes he'd start to relax. But this is Miami, where there's more crime than sunshine and corruption is as common as white shoes. So, quickly, Dolan turns up murdered. The police assume Dolan had resisted a crackhead robbery. Janice, Deal's estranged wife who worked for Dolan, suspects something more sinister.