[email protected] E-ISSN 2300-6250 the Electronic Version of Crossroads

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Cubans

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Cubans and the Caribbean South: Race, Labor, and Cuban Identity in Southern Florida, 1868-1928 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Andrew Gomez 2015 © Copyright by Andrew Gomez 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Cubans and the Caribbean South: Race, Labor, and Cuban Identity in Southern Florida, 1868- 1928 by Andrew Gomez Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Frank Tobias Higbie, Chair This dissertation looks at the Cuban cigar making communities of Key West and Ybor City (in present-day Tampa) from 1868 to 1928. During this period, both cities represented two of largest Cuban exile centers and played critical roles in the Cuban independence movement and the Clear Havana cigar industry. I am charting how these communities wrestled with race, labor politics, and their own Cuban identity. Broadly speaking, my project makes contributions to the literature on Cuban history, Latino history, and transnational studies. My narrative is broken into two chronological periods. The earlier period (1868-1898) looks at Southern Florida and Cuba as a permeable region where ideas, people, and goods flowed freely. I am showing how Southern Florida was constructed as an extension of Cuba and that workers were part of broader networks tied to Cuban nationalism and Caribbean radicalism. Borne out of Cuba’s independence struggles, both communities created a political and literary atmosphere that argued for an egalitarian view of a new republic. Concurrently, workers began to ii experiment with labor organizing. Cigar workers at first tried to reconcile the concepts of nationalism and working-class institutions, but there was considerable friction between the two ideas. -

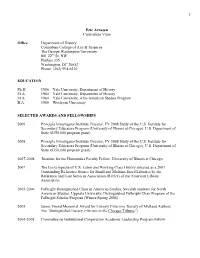

Arnesen CV GWU Website June 2009

1 Eric Arnesen Curriculum Vitae Office Department of History Columbian College of Arts & Sciences The George Washington University 801 22nd St. NW Phillips 335 Washington, DC 20052 Phone: (202) 994-6230 EDUCATION Ph.D. 1986 Yale University, Department of History M.A. 1984 Yale University, Department of History M.A. 1984 Yale University, Afro-American Studies Program B.A. 1980 Wesleyan University SELECTED AWARDS AND FELLOWSHIPS 2009 Principle Investigator/Institute Director, FY 2008 Study of the U.S. Institute for Secondary Educators Program (University of Illinois at Chicago), U.S. Department of State ($350,000 program grant) 2008 Principle Investigator/Institute Director, FY 2008 Study of the U.S. Institute for Secondary Educators Program (University of Illinois at Chicago), U.S. Department of State ($350,000 program grant) 2007-2008 Institute for the Humanities Faculty Fellow, University of Illinois at Chicago 2007 The Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working Class History selected as a 2007 Outstanding Reference Source for Small and Medium-Sized Libraries by the Reference and User Services Association (RUSA) of the American Library Association. 2005-2006 Fulbright Distinguished Chair in American Studies, Swedish Institute for North American Studies, Uppsala University, Distinguished Fulbright Chair Program of the Fulbright Scholar Program (Winter-Spring 2006) 2005 James Friend Memorial Award for Literary Criticism, Society of Midland Authors (for “distinguished literary criticism in the Chicago Tribune”) 2004-2005 Committee on Institutional -

Sesiune Speciala Intermediara De Repartitie - August 2018 DACIN SARA Aferenta Difuzarilor Din Perioada 01.04.2008 - 31.03.2009

Sesiune speciala intermediara de repartitie - August 2018 DACIN SARA aferenta difuzarilor din perioada 01.04.2008 - 31.03.2009 TITLU TITLU ORIGINAL AN TARA R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 R6 R7 R8 R9 S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 S9 S10 S11 S12 S13 S14 S15 A1 A2 3:00 a.m. 3 A.M. 2001 US Lee Davis Lee Davis 04:30 04:30 2005 SG Royston Tan Royston Tan Liam Yeo 11:14 11:14 2003 US/CA Greg Marcks Greg Marcks 1941 1941 1979 US Steven Bob Gale Robert Zemeckis (Trecut, prezent, viitor) (Past Present Future) Imperfect Imperfect 2004 GB Roger Thorp Guy de Beaujeu 007: Viitorul e in mainile lui - Roger Bruce Feirstein - 007 si Imperiul zilei de maine Tomorrow Never Dies 1997 GB/US Spottiswoode ALCS 10 produse sau mai putin 10 Items or Less 2006 US Brad Silberling Brad Silberling 10.5 pe scara Richter I - Cutremurul I 10.5 I 2004 US John Lafia Christopher Canaan John Lafia Ronnie Christensen 10.5 pe scara Richter II - Cutremurul II 10.5 II 2004 US John Lafia Christopher Canaan John Lafia Ronnie Christensen 100 milioane i.Hr / Jurassic in L.A. 100 Million BC 2008 US Griff Furst Paul Bales 101 Dalmatians - One Hamilton Luske - Hundred and One Hamilton S. Wolfgang Bill Peet - William 101 dalmatieni Dalmatians 1961 US Clyde Geronimi Luske Reitherman Peed EG/FR/ GB/IR/J Alejandro Claude Marie-Jose 11 povesti pentru 11 P/MX/ Gonzalez Amos Gitai - Lelouch - Danis Tanovic - Alejandro Gonzalez Amos Gitai - Claude Lelouch Danis Tanovic - Sanselme - Paul Laverty - Samira septembrie 11'09''01 - September 11 2002 US Inarritu Mira Nair SACD SACD SACD/ALCS Ken Loach Sean Penn - ALCS -

San Francisco Chronicle Jan. 1997 DEAL on ICE by Les Standiford

San Francisco Chronicle Jan. 1997 DEAL ON ICE By Les Standiford HarperCollins; 256 pp. A swelling number of readers insist that in the steamy literary sleazeworld of South Florida that's home to Elmore Leonard, Paul Levine, James Hall, Edna Buchanan and Carl Hiaasen there's no smoother nor more substantial crime novelist than Miami's Les Standiford. In the fourth and most sophisticated of his Deal thrillers, Standiford once again packs maximum mayhem per page into what should be the happy life of John Deal, successful building contractor and accidental sleuth. When we first see Deal this time, he's waking in the wee hours to find a Pat Boone lookalike interviewing a stylish gray-haired man on t.v. "We're moving toward the One World government," says right-wing televangelist James Ray Willis, "the rise of the Global Plantation." Preaching to the marginalized multitudes, Willis cajoles them to his flock by insisting the enemy "international media” makes them feel like failures. To clear his soul, Deal heads to the quality independent bookstore of his old friend Arch Dolan, where years earlier he'd heard Isaac Bashevis Singer and James Baldwin, because "no matter what was wrong with the momentary world, he could walk into Arch's, start wandering the rooms, in a couple of minutes he'd start to relax. But this is Miami, where there's more crime than sunshine and corruption is as common as white shoes. So, quickly, Dolan turns up murdered. The police assume Dolan had resisted a crackhead robbery. Janice, Deal's estranged wife who worked for Dolan, suspects something more sinister. -

Expansionism at the Frick Collection: the Historic Cycle of Build, Destroy, Rebuild

Expansionism at The Frick Collection: The Historic Cycle of Build, Destroy, Rebuild by Jacquelyn M. Walsh A thesis submitted to the Graduate School – New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Art History Written under the direction of Michael J. Mills, FAIA And approved by __________________________ __________________________ __________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2016 © 2016 Jacquelyn M. Walsh ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Expansionism at The Frick Collection: The Historic Cycle of Build, Destroy, Rebuild by JACQUELYN WALSH Thesis Director: Michael Mills, FAIA This thesis contends that if landscape architecture is not accorded status equal to that of architecture, then it becomes difficult, if not impossible, to convey significance and secure protective preservation measures. The sensibilities and protections of historic landscape preservation designations, particularly with respect to urban landmarked sites, played a critical role in the recent debate surrounding The Frick Collection in New York City. In June 2014, The Frick Collection announced plans to expand its footprint on the Upper East Side. Controversy set in almost immediately, presenting the opportunity to discuss in this thesis the evolution of an historic institution’s growth in which a cycle of build, destroy and rebuild had emerged. The thesis discusses the evolving status of landscape preservation within urban centers, citing the Frick Collection example of historic landscape in direct opposition to architectural construction. Archival and scholarly materials, media reports, landmark decisions, and advocacy statements illustrate the immediacy and applicability of historic persons, architecture, decisions and designations to the present day. -

An Evening with Les Standiford

April 6, 2018 Dear Friends of Prologue, On behalf of our Board, I am very happy to announce that, before we bring this spectacular 25th season of The Prologue Society to a close, one more special event has been added to the lineup! On Friday, May 11, we will be hosting a cocktail event at Riviera Country Club from 6:30-8:30pm, where our featured guest speakers will be local author Les Standiford, in conversation with South Florida mover-and-shaker Stuart Blumberg, about Les' brand new book about The Adrienne Arsht Center, Center of Dreams: Building a World-Class Performing Arts Complex in Miami. We hope that you will immediately register for this event, as it is sure to be well-attended, and we have every intention of opening registration to friends of Brickell Avenue Literary Society and the Arsht Center. It’s best to call me if you plan to mail in or bring your event fee, so that you’re sure to have a seat at the event! (Please leave me a voice mail message, if I miss your call.) Best, Debbie Hirshson Program Coordinator 786-529-0990 Enclosures An evening with Les Standiford (Center of Dreams) in conversation with Stuart Blumberg Riviera Country Club | 1155 Blue Road, Coral Gables Friday, May 11, 2018 from 6:30-8:30pm Center of Dreams: Building a World-Class Performing Arts Complex in Miami Discover how one spectacular building project revolutionized Miami, how one man's moxie helped turn a fractious tropical city into a cultural capital of the Americas. -

First Draft Written by and for the Guppies, a Chapter of Sisters in Crime

November 1, 2017 Vol. 21, No. 6 First Draft Written by and for the Guppies, a chapter of Sisters in Crime www.sinc-guppies.org Inside this issue: The President’s Message by Debra H. Goldstein he President’s column usually stresses live in an Ozzie and Harriett or Leave it to Editor’s Note 2 Welcome New Guppies T the good things and good people that Beaver world. Then again, I never did. I grew make the Guppies what it is. This month, I up with protests, Vietnam, and the history of Upcoming Classes 3 intended to congratulate us, as the largest Kent State, but I also grew up feeling safe Sisters in Crime chapter, for exceeding the wandering the streets of London at sunrise to Boas and Kick Lines 7 700-member mark. I thought I might remind see if char ladies really exist, running down a you no matter whether you are street in Boston, hearing a con- Guppy Anthology 8 starting out or already an estab- cert in Las Vegas, dancing at a lished writer, volunteering for club in Florida, flying in and out Agent Insight 9 tasks (we need two new Agent of Paris, and kissing my chil- Social Media 11 Quest monitors), taking classes, dren good-bye as they went off or participating in critique groups to spend school years abroad. Dorothy Cannell Guppy 12 or on the Listserv is an excellent History teaches us the sins of Scholarship means to learn and network. hatred and violence accomplish Diverse Voices 13 Networking, even though an nothing except decimating hu- The Editor’s POV 14 internet connection, brings us manity, so why are they repeat- closer together as a community. -

Responses to M*A*S*H, Catch 22 and Kelly's Heroes

Responses to M*A*S*H, Catch 22 and Kelly’s Heroes: Developing a Method of Investigating Changes in Discourse Timothy Simon Whittlesea Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of East Anglia School of Art, Media & American Studies June 2017 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. 2 Abstract The war-comedy films M*A*S*H and Catch 22 are frequently discussed in academia as related to the anti-Vietnam War movement and the counterculture movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Kelly’s Heroes, also a war-comedy film released in 1970, and thematically similar to M*A*S*H and Catch 22, is rarely discussed as such. This research suggests that the relationship these films have with the Vietnam War may be overstated, misrepresented or more complicated than previously thought. In examining this relationship the research presented here explores a methodology which seeks to trace changes within the critical and academic discourses which surround the three films. Rather than assessing and attempting to understand the film texts in isolation, this thesis assesses the (often changing) meanings that have been associated with them since they were released, to provide a more holistic expansive understanding of their perceived position in North American culture. To do this a method was developed that sought to contextualise and analyse the reviews, marketing material and newspaper articles related to the films. -

Press of Florida • April 2018

Tells the definitive and important story of how the Adrienne Arsht Center came to be the crown jewel of the performing arts in the great, “diverse city of Miami, setting the bar for all cultural art venues that have followed in its path.” —Emilio Estefan “An important story of selfless human spirit overcoming the conflicting obstacles of political, private, and market conditions.” —Stephen Placido, ASTC, vice president, TSG Design Solutions, Inc. “In a class by itself. A compelling saga that will make everyone feel part of the journey from concept to completion.” —Arva Moore Parks, author of George Merrick, Son of the South Wind: Visionary Creator of Coral Gables “Navigates the political and practical realities of priorities among architects, acousticians, theater consultants, fund-raising specialists and local producers. Reads like a well-crafted mystery with several twists and turns built into the plot.” HAT PEOPLE ARE SAYING ARE PEOPLE HAT —Michael Blachly, senior advisor, Arts Consulting Group W Center of Dreams Building a World-Class Performing Arts Complex in Miami LES STANDIFORD 978-0-8130-5672-2 • Hardcover $24.95 • 256 pages, 6 x 9 UNIVERSITY PRESS OF FLORIDA • APRIL 2018 For more information, contact the UPF Marketing Department: (352) 392-1351 x 232 | [email protected] Available for purchase from booksellers worldwide. To order direct from the publisher, call the University Press of Florida: 1 (800) 226-3822. Credit: Garry Kravit Credit: LES STANDIFORD is the author of twenty previous books and novels, including Last Train to Paradise: Henry Flagler and the Amazing Rise and Fall of the Railroad that Crossed an Ocean as well as eight novels in the John Deal mystery se- ries. -

Book Passage Cruise Through New Releases by Local Authors

Book Passage Cruise through new releases by local authors By Tina Koenig With gas prices over $4 a gallon, there’s certainly motivation to give your tires a rest. But that’s no excuse for intellectual idling. What more economical way to escape than between the pages of a good book? We’re serving up fresh ink by local writers. Whether you prefer reading with your elbows buried in the sand, feet propped up on a cooler, or listening at home while snuggled to your favorite electronic device, there’s reading covering myriad interests. Fiction readers who appreciate intelligent writing will enjoy unraveling what is and what isn’t in John Dufresne’s fictionalized version of his childhood. Summer thrills and sleuthing are courtesy Barbara Parker, Neil Plakcy and Elaine Viets. Nonfiction choices include more high jinks from Carl Hiaasen, the collected works of a love pollster, and several books on local and U.S. history. And because poetry gets scant attention except in April, we hope you’ll consider (modifying a phrase from Milton) “how your light is spent” and read one or two. Fiction Carl Hiaasen riffs on golf as only he can in The Downhill Lie: A Hacker's Return to a Ruinous Sport, one of the summer reading-ready books by local authors Requiem, Mass.: A Novel By John Dufresne Book a flight this summer toRequiem, Mass. (W.W. Norton; $24.95), but be forewarned, not a lot of good things happen to the residents there. Johnny’s mom, Frances, thinks her kids are aliens posing as her real children. -

Summer 2009 Three Rivers Press Catalog

you better believe it: true stories, truly great reads three rivers press summer 2009 ALL eBOOK PRICING MATCHES THE HARDCOVER/ PAPERBACK COUNTERPART ctaoblenotf ents FRONT LIST 4 AGENTS 70 FOREIGN REPS 71 AUTHOR/TITLE INDEX 72 ORDERING INFORMATION 74 “A deeply satisfying novel…Bohjalian spins a suspenseful tale in which the plot triumphs over any single sorrow.” —Washington Post Book World “Harrowing…ingenious…compelling. That Bohjalian can extract greater truths about faith, hope, and compassion from something as mundane as a diary is testament not only to his skill as a writer but also to the enduring abil - ity of well-written war fiction to stir our deepest emotions.” —los angeles times “[Bohjalian’s] sense of character and place, his skillful plotting, and his clear grasp of this confusing period of history make for a deeply satisfying novel.” —Boston gloBe “While creating suspense, Bohjalian agilely balances the moral ambiguities of war.” — Usa today “A bittersweet story of romance, war, and death, inspired in part by a real diary…Strongly dramatic and full of the heartbreaking horror of war, this novel is Bohjalian at his imaginative best.” —hartford CoUrant Skeletons at the Feast Chris Bohjalian THREE RIVERS PRESS • FEBRUARY A neW york times BESTSELLER A PUBlishers Weekly BESTSELLER A Booksense SELECTION FOREIGN RIGHTS SOLD ACROSS EUROPE AN NBC today SHOW TOP TEN SUMMER READ National Publicity Bestselling author Chris Bohjalian returns 21-City Author Tour with a tale of love and war that multiple Ann Arbor Milwaukee Austin Minneapolis critics have hailed as “harrowing,” “poignant,” Boston New Hampshire Boulder Portland, ME and “nail-biting”—and compared to both The Denver Raleigh Houston San Diego Kite Runner and The Diary of Anne Frank. -

Regional Aspects of Miami Crime Fiction Heidi Lee Alvarez Florida International University

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 2-19-1999 Regional aspects of Miami crime fiction Heidi Lee Alvarez Florida International University DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI14031604 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Alvarez, Heidi Lee, "Regional aspects of Miami crime fiction" (1999). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1263. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/1263 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida REGIONAL ASPECTS OF MIAMI CRIME FICTION A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in ENGLISH by Heidi Lee Alvarez 1999 To: Dean Arthur W. Herriott College of Arts and Sciences This thesis, written by Heidi Lee Alvarez, and entitled Regional Aspects of Miami Crime Fiction, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. Mary ne Ek's Gregory Bowe Kenneth Johnson. Major Professor Date of Defense: March 19, 1999 The thesis of Heidi Lee Alvarez is approved. Dean Arthur W. Herriott College pf Arts and Spjences Dean Richard L. Camp ell Division of Graduate Studies Florida International University, 1999 ii © Copyright 1999 by Heidi Lee Alvarez All rights reserved.