Expansionism at the Frick Collection: the Historic Cycle of Build, Destroy, Rebuild

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smithsonian Institution Archives (SIA)

SMITHSONIAN OPPORTUNITIES FOR RESEARCH AND STUDY 2020 Office of Fellowships and Internships Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC The Smithsonian Opportunities for Research and Study Guide Can be Found Online at http://www.smithsonianofi.com/sors-introduction/ Version 2.0 (Updated January 2020) Copyright © 2020 by Smithsonian Institution Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 How to Use This Book .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Anacostia Community Museum (ACM) ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 Archives of American Art (AAA) ....................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Asian Pacific American Center (APAC) .......................................................................................................................................................... 6 Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage (CFCH) ...................................................................................................................................... 7 Cooper-Hewitt, -

Helen Frick and the True Blue Girls

Helen Frick and the True Blue Girls Jack E. Hauck Treasures of Wenham History, Helen Frick Pg. 441 Helen Frick and the True Blue Girls In Wenham, for forty-five years Helen Clay Frick devoted her time, her resources and her ideas for public good, focusing on improving the quality of life of young, working-class girls. Her style of philanthropy went beyond donating money: she participated in helping thousands of these girls. It all began in the spring of 1909, when twenty-year-old Helen Frick wrote letters to the South End Settlement House in Boston, and to the YMCAs and churches in Lowell, Lawrence and Lynn, requesting “ten promising needy Protestant girls to be selected for a free two-week stay ”in the countryside. s In June, she welcomed the first twenty-four young women, from Lawrence, to the Stillman Farm, in Beverly.2, 11 All told, sixty-two young women vacationed at Stillman Farm, that first summer, enjoying the fresh air, open spaces and companionship.2 Although Helen monitored every detail of the management and organization, she hired a Mrs. Stefert, a family friend from Pittsburgh, to cook meals and run the home.2 Afternoons were spent swimming on the ocean beach at her family’s summer house, Eagle Rock, taking tea in the gardens, or going to Hamilton to watch a horse show or polo game, at the Myopia Hunt Club.2 One can only imagine how awestruck these young women were upon visiting the Eagle Rock summer home. It was a huge stone mansion, with over a hundred rooms, expansive gardens and a broad view of the Atlantic Ocean. -

Reading Guide in Sunlight, in a Beautiful Garden

Reading Guide In Sunlight, in a Beautiful Garden By Kathleen Cambor ISBN: 9780060007577 Johnstown, Pennsylvania 1889 So deeply sheltered and surrounded was the site that it was as if nature's true intent had been to hide the place, to keep men from it, to let the mountains block the light and the trees grow as thick and gnarled as the thorn-dense vines that inundated Sleeping Beauty's castle. Perhaps, some would say, years later, that was central to all that happened. That it was a city that was never meant to be. IntroductionOn May 31, 1889, the unthinkable happened. The dam supporting an artificial lake at the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, playground to wealthy and powerful financiers Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, and Andrew Mellon, collapsed. It was one of the greatest disasters in post-Civil War America. Some 2,200 lives were lost in the Johnstown, Pennsylvania, flood. In the shadow of the Johnstown dam live Frank and Julia Fallon, devastated by the loss of two children; their surviving son, Daniel, a passionate opponent of industrial greed; Grace McIntyre, a newcomer with a secret; and Nora Talbot, a lawyer's daughter, who is both bound to and excluded from the club's society. As Frank and Julia, seemingly incapable of repairing their marriage, look to Grace for solace and friendship, Daniel finds himself inexplicably drawn to Nora, daughter of a wealthy family from Pittsburgh. James, Nora's father, struggles with his conscience after bending the law to file the club's charter and becomes increasingly concerned about the safety of the dam. -

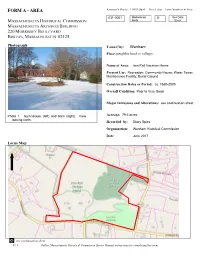

FORM a - AREA Assessor’S Sheets USGS Quad Area Letter Form Numbers in Area

FORM A - AREA Assessor’s Sheets USGS Quad Area Letter Form Numbers in Area 031-0001 Marblehead G See Data MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL COMMISSION North Sheet ASSACHUSETTS RCHIVES UILDING M A B 220 MORRISSEY BOULEVARD BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02125 Photograph Town/City: Wenham Place (neighborhood or village): Name of Area: Iron Rail Vacation Home Present Use: Recreation; Community House; Water Tower; Maintenance Facility; Burial Ground Construction Dates or Period: ca. 1880-2009 Overall Condition: Poor to Very Good Major Intrusions and Alterations: see continuation sheet Photo 1. Gymnasium (left) and barn (right). View Acreage: 79.6 acres looking north. Recorded by: Stacy Spies Organization: Wenham Historical Commission Date: June 2017 Locus Map see continuation sheet 4 /1 1 Follow Massachusetts Historical Commission Survey Manual instructions for completing this form. INVENTORY FORM A CONTINUATION SHEET WENHAM IRON RAIL VACATION HOME MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL COMMISSION Area Letter Form Nos. 220 MORRISSEY BOULEVARD, BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02125 G See Data Sheet Recommended for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. If checked, you must attach a completed National Register Criteria Statement form. Use as much space as necessary to complete the following entries, allowing text to flow onto additional continuation sheets. ARCHITECTURAL DESCRIPTION Describe architectural, structural and landscape features and evaluate in terms of other areas within the community. The Iron Rail Vacation Home property at 91 Grapevine Road is comprised of buildings and landscape features dating from the multiple owners and uses of the property over the 150 years. The extensive property contains shallow rises surrounded by wetlands. Woodlands are located at the north half of the property and wetlands are located at the northwest and central portions of the property. -

American Folk Art from the Volkersz Collection the Fine Arts Center Is an Accredited Member of the American Alliance of Museums

Strange and Wonderful American Folk Art from the Volkersz Collection The Fine Arts Center is an accredited member of the American Alliance of Museums. We are proud to be in the company of the most prestigious institutions in the country carrying this important designation and to have been among the first group of 16 museums The Fine Arts Center is an accredited member of the American Alliance of Museums. We are proud to be in the company of the most accredited by the AAM in 1971. prestigious institutions in the country carrying this important designation and to have been among the first group of 16 museums accredited by the AAM in 1971. Copyright© 2013 Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center Copyright © 2013 Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Strange and Wonderful: American Folk Art from the Volkersz Collection. Authors: Steve Glueckert; Tom Patterson Charles Bunnell: Rocky Mountain Modern. Authors: Cori Sherman North and Blake Milteer. Editor: Amberle Sherman. ISBN 978-0-916537-16-6 Published on the occasion of the exhibition Strange and Wonderful: American Folk Art from the Volkersz Collection at the Missoula Art 978-0-916537-15-9 Museum, September 22 – December 22, 2013 and the Colorado Spring Fine Arts Center, February 8 - May 18, 2014 Published on the occasion of the exhibition Charles Bunnell: Rocky Mountain Modern at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, Printed by My Favorite Printer June 8 – Sept. 15, 2013 Projected Directed and Curated by Sam Gappmayer Printed by My Favorite Printer Photography for all plates by Tom Ferris. -

Nyc-Cation” in All Five Boroughs August 28–30

***MEDIA ADVISORY*** THIS WEEKEND IN NYC: TAKE A “NYC-CATION” IN ALL FIVE BOROUGHS AUGUST 28–30 NYC & Company, the official destination marketing organization and convention and visitors bureau for the five boroughs of New York City, is encouraging locals and regional visitors to take a “NYC-cation” this weekend, August 28–30, by heading to a museum in Manhattan, the New York Aquarium in Brooklyn or grabbing lunch and swimming in Queens. CONTACTS Chris Heywood/ This week, museums and cultural institutions begin to reopen in NYC, offering Alyssa Schmid locals and regional visitors even more places to explore and reinvigorating the NYC & Company destination as an arts and culture capital. 212-484-1270 [email protected] Visitors to the five boroughs are encouraged to wear masks, practice social Mike Stouber Rubenstein distancing and frequently wash/sanitize hands, as indicated in NYC & 732-259-9006 Company’s Stay Well NYC Pledge. [email protected] DATE Below is a brief selection of what’s open this weekend, including museums August 27, 2020 and places to visit on the water: The Bronx: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage. This weekend, take a trip to Woodlawn Cemetery to honor a few of the women who helped shape this country today, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who was also buried there. Other notable figures interred in the 400-acre cemetery include artists and writers, business moguls, civic leaders, entertainers, jazz musicians, and more, with names including Miles Davis, Robert Moses, Nellie Bly, Duke Ellington, Herman Melville and more. -

Topics in Modern Architecture in Southern California

TOPICS IN MODERN ARCHITECTURE IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA ARCH 404: 3 units, Spring 2019 Watt 212: Tuesdays 3 to 5:50 Instructor: Ken Breisch: [email protected] Office Hours: Watt 326, Tuesdays: 1:30-2:30; or to be arranged There are few regions in the world where it is more exciting to explore the scope of twentieth-century architecture than in Southern California. It is here that European and Asian influences combined with the local environment, culture, politics and vernacular traditions to create an entirely new vocabulary of regional architecture and urban form. Lecture topics range from the stylistic influences of the Arts and Crafts Movement and European Modernism to the impact on architecture and planning of the automobile, World War II, or the USC School of Architecture during the 1950s. REQUIRED READING: Thomas S., Hines, Architecture of the Sun: Los Angeles Modernism, 1900-1970, Rizzoli: New York, 2010. You can buy this on-line at a considerable discount. Readings in Blackboard and online. Weekly reading assignments are listed in the lecture schedule in this syllabus. These readings should be completed before the lecture under which they are listed. RECOMMENDED OPTIONAL READING: Reyner Banham, Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies, 1971, reprint ed., Berkeley; University of California Press, 2001. Barbara Goldstein, ed., Arts and Architecture: The Entenza Years, with an essay by Esther McCoy, 1990, reprint ed., Santa Monica, Hennessey and Ingalls, 1998. Esther McCoy, Five California Architects, 1960, reprint ed., New York: -

Eighteen Major New York Area Museums Participate in Instagram Swap

EIGHTEEN MAJOR NEW YORK AREA MUSEUMS PARTICIPATE IN INSTAGRAM SWAP THE FRICK COLLECTION PAIRS WITH NEW-YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY In a first-of-its-kind collaboration, eighteen major New York City area institutions have joined forces to celebrate their unique collections and spaces on Instagram. All day today, February 2, the museums will post photos from this exciting project. Each participating museum paired with a sister institution, then set out to take photographs at that institution, capturing objects and moments that resonated with their own collections, exhibitions, and themes. As anticipated, each organization’s unique focus offers a new perspective on their partner museum. Throughout the day, the Frick will showcase its recent visit to the New-York Historical Society on its Instagram feed using the hashtag #MuseumInstaSwap. Posts will emphasize the connections between the two museums and libraries, both cultural landmarks in New York and both beloved for highlighting the city’s rich history. The public is encouraged to follow and interact to discover what each museum’s Instagram staffer discovered in the other’s space. A complete list of participating museums follows: American Museum of Natural History @AMNH The Museum of Modern Art @themuseumofmodernart Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum @intrepidmuseum Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum @cooperhewitt Museum of the City of New York @MuseumofCityNY New Museum @newmuseum 1 The Museum of Arts and Design @madmuseum Whitney Museum of American Art @whitneymuseum The Frick Collection -

CATALOG NO. 1 Artists’ Ephemera, Exhibition Documents and Rare and Out-Of-Print Books on Art, Architecture, Counter-Culture and Design 1

CATALOG NO. 1 Artists’ Ephemera, Exhibition Documents and Rare and Out-of-Print Books on Art, Architecture, Counter-Culture and Design 1. IMAGE BANK PENCILS Vancouver Canada Circa 1970. Embossed Pencils, one red and one blue. 7.5 x .25” diameter (19 x 6.4 cm). Fine, unused and unsharpened. $200 Influenced by their correspondence with Ray Johnson, Michael Morris and Vincent Trasov co- founded Image Bank in 1969 in Vancouver, Canada. Paralleling the rise of mail art, Image Bank was a collaborative, postal-based exchange system between artists; activities included requests lists that were published in FILE Magazine, along with publications and documents which directed the exchange of images, information, and ideas. The aim of Image Bank was an inherently anti- capitalistic collective for creative conscious. 2. AUGUSTO DE CAMPOS: CIDADE=CITY=CITÉ Edinburgh Scotland 1963/1964. Concrete Poem, letterpressed. 20 x 8” (50.8 x 20.3 cm) when unfolded. Very Good, folded as issued, some toning at edges, very slight soft creasing at folds and edges. $225. An early concrete poetry work by Augusto de Campos and published by Ian Hamilton Finlay’s Wild Hawthorn Press. Campos is credited as a co-founder (along with his brother Haroldo) of the concrete poetry movement in Brazil. His work with the poem Cidade=City=Cité spanned many years, and included various manifestations: in print (1960s), plurivocal readings and performances (1980s-1990s), and sculpture (1987, São Paulo Biennial). The poem contains only prefixes in the languages of Portuguese, English and French which are each added to the suxes of cidade, city and cité to form trios of words with the same meaning in each language. -

The Henry Darger Study Center at the American Folk Art Museum a Collections Policy Recommendation Report

The Henry Darger Study Center at the American Folk Art Museum A Collections Policy Recommendation Report by Shannon Robinson Spring 2010 I. Overview page 3 II. Mission and Goals page 5 III. Service Community and Programs page 7 IV. The Collection and Future Acquisition page 8 V. Library Selection page 11 VI. Responsibilities page 12 VII. Complaints and Censorship page 13 VIII. Evaluation page 13 IX. Bibliography page 15 X. Additional Materials References page 16 I. Overview The American Folk Art Museum in New York City is largely focused on the collection and preservation of the artwork of self-taught artists in the United States and abroad. The Museum began in 1961 as the Museum of Early American Folk Arts; at that time, the idea of appreciating folk art alongside contemporary art was a consequence of modernism (The American Folk Art Museum, 2010c). The collection’s pieces date to as early as the eighteenth century and in it’s earlier days was largely comprised of sculpture. The Museum approached collecting and exhibiting much like a contemporary art gallery. This was in support of its mission promoting the “aesthetic appreciation” and “creative expressions” of folk artists as parallel in content and quality to more mainstream, trained artists. (The American Folk Art Museum, 2010b). Within ten years of opening, however, and though the collection continued to grow, a financial strain hindered a bright future for the Museum. In 1977, the Museum’s Board of Trustees appointed Robert Bishop director (The American Folk Art Museum, 2010c). While Bishop was largely focused on financial and facility issues, he encouraged gift acquisitions, and increasing the collection in general, by promising many artworks from his personal collection. -

Youth Guide to the Department of Youth and Community Development Will Be Updating This Guide Regularly

NYC2015 Youth Guide to The Department of Youth and Community Development will be updating this guide regularly. Please check back with us to see the latest additions. Have a safe and fun Summer! For additional information please call Youth Connect at 1.800.246.4646 T H E C I T Y O F N EW Y O RK O FFI CE O F T H E M AYOR N EW Y O RK , NY 10007 Summer 2015 Dear Friends: I am delighted to share with you the 2015 edition of the New York City Youth Guide to Summer Fun. There is no season quite like summer in the City! Across the five boroughs, there are endless opportunities for creation, relaxation and learning, and thanks to the efforts of the Department of Youth and Community Development and its partners, this guide will help neighbors and visitors from all walks of life savor the full flavor of the city and plan their family’s fun in the sun. Whether hitting the beach or watching an outdoor movie, dancing under the stars or enjoying a puppet show, exploring the zoo or sketching the skyline, attending library read-alouds or playing chess, New Yorkers are sure to make lasting memories this July and August as they discover a newfound appreciation for their diverse and vibrant home. My administration is committed to ensuring that all 8.5 million New Yorkers can enjoy and contribute to the creative energy of our city. This terrific resource not only helps us achieve that important goal, but also sustains our status as a hub of culture and entertainment. -

The Frick Collection

THE FRICK COLLECTION Building Upgrade and Expansion Fact Sheet Project Description: Honoring the architectural legacy and unique character of the Frick, the design for the upgrade and expansion by Selldorf Architects provides unprecedented access to the original 1914 home of Henry Clay Frick, preserves the intimate visitor experience and beloved galleries for which the Frick is known, and revitalizes the 70th Street Garden. Conceived to address pressing institutional and programmatic needs, the new plan creates new resources for permanent collection display and special exhibitions, conservation, and education and public programs, while upgrading visitor amenities and overall accessibility. The project marks the first comprehensive upgrade to the Frick’s buildings since the institution opened to the public eighty-two years ago in 1935. Groundbreaking: 2020 Location: 1 East 70th Street, New York, NY 10021 Square Footage: Current: 179,000 square feet Future: 197,000 square feet (10% increase) * *Note that this figure takes into consideration new construction as well as the loss of existing space resulting from the elimination of mezzanine levels in the library. Project Breakdown: Repurposed Space: 60,000 square feet New Construction: 27,000 square feet* **Given that 9,000 square feet of library stack space is removed through repurposing, the construction nets a total additional space of 18,000 square feet. Building Features & New Amenities: • 30% more gallery space for the collection and special exhibitions: o a series of approximately twelve