Lewis and Clark's White Salmon Trout: Coho

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biological Assessment

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 1 2 BACKGROUND INFORMATION .................................................................................................................... 1 3 PROPOSED ACTION ................................................................................................................................. 2 3.1 Project Area ............................................................................................................................... 2 3.2 Proposed Action ........................................................................................................................ 4 3.2.1 Current Permit ....................................................................................................................... 4 3.2.2 Grazing System ..................................................................................................................... 4 3.2.3 Conservation Measures ........................................................................................................ 5 3.2.4 Changes From Existing Management ................................................................................... 5 3.2.5 Resource Objectives and Standards .................................................................................... 6 3.2.6 Annual Grazing Use indicators .............................................................................................. 7 -

George Drouillard and John Colter: Heroes of the American West Mitchell Edward Pike Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2012 George Drouillard and John Colter: Heroes of the American West Mitchell Edward Pike Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Pike, Mitchell Edward, "George Drouillard and John Colter: Heroes of the American West" (2012). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 444. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/444 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE GEORGE DROUILLARD AND JOHN COLTER: HEROES OF THE AMERICAN WEST SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR LILY GEISMER AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY MITCHELL EDWARD PIKE FOR SENIOR THESIS SPRING/2012 APRIL 23, 2012 Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………..4 Chapter One. George Drouillard, Interpreter and Hunter………………………………..11 Chapter Two. John Colter, Trailblazer of the Fur Trade………………………………...28 Chapter 3. Problems with Second and Firsthand Histories……………………………....44 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………….……55 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………..58 Introduction The United States underwent a dramatic territorial change during the early part of the nineteenth century, paving the way for rapid exploration and expansion of the American West. On April 30, 1803 France and the United States signed the Louisiana Purchase Treaty, causing the Louisiana Territory to transfer from French to United States control for the price of fifteen million dollars.1 The territorial acquisition was agreed upon by Napoleon Bonaparte, First Consul of the Republic of France, and Robert R. Livingston and James Monroe, both of whom were acting on behalf of the United States. Monroe and Livingston only negotiated for New Orleans and the mouth of the Mississippi, but Napoleon in regard to the territory said “I renounce Louisiana. -

Table of Contents (PDF)

DM - L & C 10/19/15 6:48 PM Page v Table of Contents Preface . ix How to Use This Book . xiii Research Topics for Defining Moments: The Lewis and Clark Expedition . xv NARRATIVE OVERVIEW Prologue . 3 Chapter 1: The Louisiana Purchase . 7 Chapter 2: The Corps of Discovery . 19 Chapter 3: Up the Missouri River, 1804 . 35 Chapter 4: Across the Continent to the Pacific, 1805 . 51 Chapter 5: The Return Journey, 1806 . 71 Chapter 6: Settlement of the West . 91 Chapter 7: Legacy of the Lewis and Clark Expedition . 105 BIOGRAPHIES Toussaint Charbonneau (c. 1760-1843) . 117 Fur Trader and Translator for the Lewis and Clark Expedition William Clark (1770-1838) . 121 Co-Captain and Primary Mapmaker of the Corps of Discovery John Colter (c. 1774-1813) . 125 Explorer, Trapper, and Member of the Corps of Discovery v DM - L & C 10/19/15 6:48 PM Page vi Defining Moments: The Lewis and Clark Expedition George Drouillard (c. 1774-1810) . 129 Interpreter and Hunter for the Lewis and Clark Expedition Patrick Gass (1771-1870) . 133 Sergeant, Carpenter, and Journal Keeper for the Corps of Discovery Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) . 137 President Who Organized the Lewis and Clark Expedition Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809) . 141 Explorer, Naturalist, and Co-Captain of the Corps of Discovery Sacagawea (c. 1788-1812) . 146 Interpreter and Guide for the Lewis and Clark Expedition York (c. 1770-c. 1822) . 150 Enslaved African-American Member of the Corps of Discovery PRIMARY SOURCES Alexander Mackenzie Inspires American Exploration . 157 President Thomas Jefferson Asks Congress to Fund an Expedition . -

Lewis & Clark Meet the Plains Bison

Museum of the American Indian -- Lisette's Fate -- Sacagawea & Susan B. Anthony Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation I www.lewisandclark.org February 2005 Volume 31, No. 1 LEWIS & CLARK MEET THE PLAINS BISON PLUS: CAPE GIRARDEAU • "SERGEANT" wARFINGTON Contents Letters: Lisette's fa te; Cape Disappointment; John Pernier 2 President's Message: National Museum of the American Indian 4 Bicentennial Council: Where did the L&C Expedition begin? 6 The Corps of Discovery's Forgotten "Sergeant" 10 Lewis and Clark entrusted Richard Warfington with responsibilities far beyond his corporal's rank By Trent Strickland Cape Girardeau and the Corps of Discovery 14 Newly discovered documents detail the post-expedition lives of four veterans of the Lewis and Clark Expedition By Jane Randol Jackson Warfington, p. 11 Great Gangues of Buffalow 22 Lewis and Clark's encounters with the plains bison By Kenneth C. Walcheck Reviews 32 Scenes of Visionary Enchantment; The L ewis and Clark Expedition; An Artist with the Corps of Discovery; Sacajawea's People; The Story of the Bitterroot; "Most Perfect Harmony" L&C Roundup: Lewis and Clark in other journals 39 Trail Notes: Stewardship initiatives 40 From the Library: L&C on the World Wide Web 43 Soundings 44 Cape Girardeau, p. 15 Sacagawea and Susan B. Anthony By Bill Smith On the cover Titled Red Shirt, artist Michael H aynes's painting shows Sergeant John Ordway surprised by a buffalo bull on a rainy September 11, 1804, while the Corps of Discovery was making its way up the Missouri River in today's South Dakota. -

Lemhi County, Idaho

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, DIRECTOR BUIJLETIN 528 GEOLOGY AND ORE DEPOSITS 1 OF LEMHI COUNTY, IDAHO BY JOSEPH B. UMPLEBY WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1913 CONTENTS. Page. Outline of report.......................................................... 11 Introduction.............................................................. 15 Scope of report......................................................... 15 Field work and acknowledgments...................................... 15 Early work............................................................ 16 Geography. .........> ....................................................... 17 Situation and access.........................--.-----------.-..--...-.. 17 Climate, vegetation, and animal life....................----.-----.....- 19 Mining................................................................ 20 General conditions.......... 1..................................... 20 History..............................-..............-..........:... 20 Production.................................,.........'.............. 21 Physiography.............................................................. 22 Existing topography.................................................... 22 Physiographic development............................................. 23 General features...............................................'.... 23 Erosion surface.................................................... 25 Correlation............. 1.......................................... -

Idaho: Lewis Clark Byway Guide.Pdf

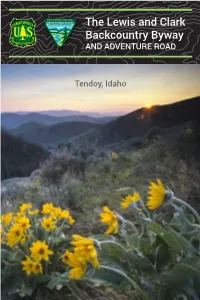

The Lewis and Clark Backcountry Byway AND ADVENTURE ROAD Tendoy, Idaho Meriwether Lewis’s journal entry on August 18, 1805 —American Philosophical Society The Lewis and Clark Back Country Byway AND ADVENTURE ROAD Tendoy, Idaho The Lewis and Clark Back Country Byway and Adventure Road is a 36 mile loop drive through a beautiful and historic landscape on the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail and the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail. The mountains, evergreen forests, high desert canyons, and grassy foothills look much the same today as when the Lewis and Clark Expedition passed through in 1805. THE PUBLIC LANDS CENTER Salmon-Challis National Forest and BLM Salmon Field Office 1206 S. Challis Street / Salmon, ID 83467 / (208)756-5400 BLM/ID/GI-15/006+1220 Getting There The portal to the Byway is Tendoy, Idaho, which is nineteen miles south of Salmon on Idaho Highway 28. From Montana, exit from I-15 at Clark Canyon Reservoir south of Dillon onto Montana Highway 324. Drive west past Grant to an intersection at the Shoshone Ridge Overlook. If you’re pulling a trailer or driving an RV with a passenger vehicle in tow, it would be a good idea to leave your trailer or RV at the overlook, which has plenty of parking, a vault toilet, and interpretive signs. Travel road 3909 west 12 miles to Lemhi Pass. Please respect private property along the road and obey posted speed signs. Salmon, Idaho, and Dillon, Montana, are full- service communities. Limited services are available in Tendoy, Lemhi, and Leadore, Idaho and Grant, Montana. -

Selections from the State Librarian with Comments Fall 2003 Through Summer 2008

Selections from the State Librarian With comments Fall 2003 through Summer 2008 Each season for the past five years Jan Walsh, Washington State Librarian, has chosen a theme and then selected at least one adult, one young adult, and one children‟s book to fit her topic. The following list is a compilation of her choices with her comments. The season in which each title was selected is listed in parentheses following its citation. Her themes were: Artists of Washington—spring 2004 Beach Reads—summer 2008 The Columbia River through Washington History—fall 2004 Courage—summer 2005 Disasters—fall 2007 Diversity—winter 2006 Exploring Washington—spring 2008 Geology of Washington State—fall 2005 Hidden People—spring 2007 Lewis, Clark, and Seaman—winter 2004 Life in Washington Territory—fall 2003 Mount St. Helens—spring 2005 Mysteries of Washington—fall 2006 Of Beaches and the Sea—winter 2008 The Olympic Peninsula—winter 2007 The Oregon Trail—spring 2006 Spokane and the Inland Empire—summer 2007 Tastes of Washington—summer 2006 Washington through the Photographer‟s Lens—summer 2004 Washington‟s Native People—winter 2005 NW prefixed books are available for check out and interlibrary loan. RARE, R (Reference), and GWA (Governor‟s Writers Award) prefixed books are available to be viewed only at the State Library. All books were in print at the time of Ms. Walsh‟s selection. January 23, 2009 1 Washington Reads 5 year compilation with Jan‟s comments Adult selections Alexie, Sherman. Reservation Blues. Grove Press, 1995. 306 p. (Summer 2007) NW 813.54 ALEXIE 1995; R 813.54 ALEXIE 1995 “The novel, which won the American Book Award in 1996, is a poignant look at the rise and fall of an Indian rock band, Coyote Springs, and the people and spirits that surround it. -

OLD Toby'' Losr? REVISITING the BITTERROOT CROSSING

The L&C Journal's 10 most-used words --- Prince Maxmilian's journals reissued ...___ Lewis_ and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation I www.lewisandclark.org August2011 Volume 37, No. 3 W As ''OLD ToBY'' Losr? REVISITING THE BITTERROOT CROSSING How Blacksmiths Fed the L&C Expedition Prince Madoc, the Welsh, and the Mandan Indians Contents Letters: 10 most popular words in the L&C Journals 2 President's Message: Proceeding on from a challenging spring 4 Was Toby Lost? s Did the Shoshone guide take "a wrong road" over the Bitterroot Mountains, as Captain William Clark contended, or was Toby following a lesser-known Indian trail? By John Puckett Forging for Food 10 How blacksmiths of the Lewis and Clark Expedition saved the Corps from starvation during the winter of 1804-1805 at Fort Mandan By Shaina Robbins Was Toby Lost? p. 5 Prince Madoc and the Welsh Indians 16 When Lewis and Clark arrived at Fort Mandan President Jefferson suggested they look for a connection between the twelfth-century Welsh prince and the Mandan Indians. Did one exist? By Aaron Cobia Review Round-up ' 21 The first two volumes of newly edited and translated North American Journals of Prince Maximilian of Wjed; the story of Captain John McClallen, the fi~st _U f..S. officer to follow the expedition west in By Honor arid Right: How One Man Boldly Defined the D estiny of a Natio~ . Endnotes: The Stories Left Behind 24 The difficult task of picking the stories to tell and the stories to leave behind in the Montana's new history textbook Forging for Food, p. -

American Philosophical Society

THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE LEWIS & CLARK TRAIL HERITAGE FOUNDATION, INC. VOL. 8 NO. 2 MAY 1982 American Philosophical Society - Philadelphia Foundation Director and Chairman colonies is pretty well over," wrote role in the cultural life of the Repub for the Foundation's 14th Annual Benjamin Franklin in 1743, "and lic for more than two centuries. Meeting, Hal Billian, Paoli, Penn there are many in every province in sylvania, has written the editor on circumstances that set them at ease, Following the Society's organiza tion in 1743, regular meetings were numerous occasions recounting the and afford leisure to cultivate the fine cooperation he has received finer art, and improve the common suspended. There were fewer men of from the principals of the various stock of knowledge." The scientific education and leisure in the colo institutions, societies, and govern and literary society for which nies than Franklin imagined. It ment agencies involved with our Franklin appealed was established was in 1769 that the Society achieved a permanent organiza August 8-11, 1982 meeting in Phila that same year. The American delphia. Foundation President Philosophical Society, held at Phila tion. From that time to the present Strode Hinds has echoed these delphia, for Promoting Useful Knowl day it has met regularly, except statements in his "President's Mes edge - to give its full title - is the when the British occupied Phila sage" on page two of this issue of oldest learned society in the United delphia during the American Revo lution. We Proceeded On. States. It has played an important Doctors, lawyers, clergymen and All the locations that annual meet journals, maps, miscellaneous papers and merchants, joined learned artisans ing registrants visit will have sig notebooks, with the Historical Committee of and tradesmen like Franklin, and the American Philosophical Society. -

Fort Atkinson at Council Bluffs

Fort Atkinson at Council Bluffs (Article begins on page 2 below.) This article is copyrighted by History Nebraska (formerly the Nebraska State Historical Society). You may download it for your personal use. For permission to re-use materials, or for photo ordering information, see: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/re-use-nshs-materials Learn more about Nebraska History (and search articles) here: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/nebraska-history-magazine History Nebraska members receive four issues of Nebraska History annually: https://history.nebraska.gov/get-involved/membership Full Citation: Sally A Johnson, “Fort Atkinson at Council Bluffs,” Nebraska History 38 (1957): 229-236 Article Summary: The author presents the history of Fort Atkinson and questions still surrounding its origins. New interest in the site of the post arose during the summer of 1956 when a Nebraska State Historical Society field party, under the direction of Marvin F Kivett, did some archeological work there. There was a bill before Congress to make the site a national monument at that time. Cataloging Information: Names: Marvin F Kivett, Lewis and Clark, John Ordway, John Colter, George Drouillard, John Potts, Peter Wiser, Manuel Lisa, Patrick Gass, S H Long, J R Bell, Henry Atkinson, John C Calhoun, T S Jessup Keywords: Missouri Trading Company, St Louis; Engineer Cantonment; Fort Lisa; Cantonment Council Bluffs; Omaha Indians; Ninth Military Department; Water Witch (lead boat in the move to Jefferson Barracks); Yellowstone Expedition Photographs / Images: Meeting of Lewis and Clark with Oto and Missouri Indians at Council Bluffs, 1804 (painting reconstructed by Herbert Thomas, staff artist, Nebraska State Historical Society) FORT ATKINSON AT COUNCIL BLUFFS BY SALLY A. -

BPA Partners with Idaho to Secure More Than 4600 Acres to Benefit Fish

BONNEVILLE POWER ADMINISTRATION Fact Sheet July 2015 BPA partners with Idaho to secure more than 4,600 acres to benefit fish Habitat conservation – PURPOSE: The Bonneville Power Administration is partially funding the purchase of a conservation public notice easement that would permanently protect nearly DATE: July 2015 10 miles of in-stream and riparian habitat near the town of Leadore in Lemhi County, Idaho. LOCATION: Leadore, Lemhi County, Idaho (see map on page 4) This acquisition will partially mitigate the impacts to salmon and steelhead from the construction, ACRES: 4,682 (nearly 10 miles of in-stream and inundation and continued operation of federal riparian habitat along the mainstem of the Lemhi River) hydroelectric dams in the Columbia River and Snake © ILONA MCCARTY OPEN VIEW PHOTOGRAPHY the elimination of a ditch on the Lemhi River and participation in a 72-hour high flow event during which water withdrawals will be curtailed to mimic or enhance channel forming and maintaining events. When combined with similar efforts on neighboring conservation easements on the Lemhi River, these actions will result in 100 cubic feet per second flowing through more than 25 miles of main river and tributary habitat. These flushing flows will help increase egg and smolt survival over time as gravels are consistently washed clean for successive brood years. SPECIES BENEFITED: Snake River spring/summer Headwaters of the Lemhi River at the confluence of Texas and chinook, steelhead Eighteen Mile creeks. Leadore Land Partners Ranch, 2012 TYPES OF LAND: In-stream and riparian River basins. The conservation of habitat is one TYPE OF ACTION: BPA is working with the Idaho component of a broader, comprehensive strategy to Office of Species Conservation and the Lemhi Regional improve conditions for fish at all stages of their life in Land Trust to negotiate a conservation easement on the river. -

Telling the Story: Changing Perceptions of the Lewis and Clark Journals

TELLING THE STORY: CHANGING PERCEPTIONS OF THE LEWIS AND CLARK JOURNALS by Deborah Malony Dukes A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Humboldt State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Social Science Emphasis: Teaching American History May 2006 TELLING THE STORY: CHANGING PERCEPTIONS OF THE LEWIS AND CLARK JOURNALS by Deborah Malony Dukes Approved by the Master’s Thesis Committee: Delores McBroome, Major Professor Date Gayle Olson-Raymer, Committee Member Date Rodney Sievers, Committee Member Date Delores McBroome, Graduate Coordinator Date Donna E. Schafer, Dean for Research and Graduate Studies Date ABSTRACT The collective journals of the Lewis and Clark expedition have been objects of fascination and interpretation ever since the Corps of Discovery’s homecoming in 1806. Despite President Thomas Jefferson’s direction that Meriwether Lewis prepare the journals for publication, Lewis’ untimely death in 1809 left the editing of the expedition’s records – and much of the storytelling – to a series of writers and editors of varying interests, abilities and degrees of integrity. Understandably the several major editions and many other versions of the story have reflected the lives and times of the editors. For instance, ornithologist Elliott Coues was the first – 89 years after the fact – to acknowledge the expedition’s many scientific and ethnological observations. For their own purposes, successive generations of activists have appropriated iconic expedition members, emphasized or even invented anecdotes, and supposed discoveries. Scholarly and public interest in the journals has peaked during this bicentennial period, as often happens around the times of major anniversaries of the expedition.