Haydn's Call for Peace: the Agnus Dei Movements of Missa in Tempore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Missa Brevis Harmoniemesse

HAYDN Missa brevis (1749) Harmoniemesse Trinity Choir • REBEL Baroque Orchestra J. Owen Burdick • Jane Glover 8.572126 Haydn masses-Missa brevis 1749 booklet.indd 1 23/09/2010 13:54 Joseph HAYDN (1732–1809) Missa brevis 11:41 in F major (Hob.XXII:1; 1749) 1 Kyrie 1:03 2 Gloria 1:34 3 Credo 2:39 4 Sanctus 0:59 5 Benedictus 2:55 6 Agnus Dei 1:27 7 Dona nobis pacem 1:04 Ann Hoyt, soprano 1 • Julie Liston, soprano 2 Richard Lippold, bass Trinity Choir Rebel Baroque Orchestra Jörg Michael Schwarz, leader J. Owen Burdick 8.572126 2 8.572126 Haydn masses-Missa brevis 1749 booklet.indd 2 23/09/2010 13:54 Joseph HAYDN (1732–1809) Missa brevis 11:41 Missa, ‘Harmoniemesse’ 40:30 in F major in B flat major (Hob.XXII:1; 1749) (Hob.XXII:14; 1802) 1 Kyrie 1:03 8 Kyrie 7:09 2 Gloria 1:34 9 Gloria 1:59 3 Credo 2:39 0 Gratias agimus tibi 5:16 4 Sanctus 0:59 ! Quoniam tu solus sanctus 3:17 5 Benedictus 2:55 @ Credo 2:44 6 Agnus Dei 1:27 # Et incarnatus est 3:04 7 Dona nobis pacem 1:04 $ Et resurrexit 2:44 % Et vitam venturi 1 2 1:45 Ann Hoyt, soprano 1 • Julie Liston, soprano 2 ^ Sanctus 2:45 Richard Lippold, bass & Benedictus 4:08 Trinity Choir * Agnus Dei 2:37 Rebel Baroque Orchestra ( Dona nobis pacem 3:02 Jörg Michael Schwarz, leader J. Owen Burdick Nacole Palmer, soprano • Nina Faia, soprano 1 Kirsten Sollek, alto • Daniel Mutlu, tenor Matthew Hensrud, tenor 2 • Andrew Nolen, bass Trinity Choir Rebel Baroque Orchestra Jörg Michael Schwarz, leader Jane Glover 3 8.572126 8.572126 Haydn masses-Missa brevis 1749 booklet.indd 3 23/09/2010 13:54 Haydn’s Masses The ‘father of the symphony’ and master of for composing in sixteen parts before I understood two- conversational wit in the string quartet, [Franz] Joseph part setting.’3 Reutter’s instruction was predominantly Haydn is viewed today principally in the light of his practical in nature; although Haydn remembered only instrumental music. -

4474134-09A1a4-Booklet-CD98.626

2.K ach intensiver Auseinandersetzung mit dem er „kritische Bericht“, dieser Inbegriff Symbole werden zu Akteuren eines unserer Nsinfonischen Werk Mozarts und Beethovens Dgeduldigsten Forscherfleißes, begegnet Imagination entspringenden Theaters und habe ich meine Liebe zu Haydns Musik zugege- abseits seines Fachbezirks vielfachem Unver- treten, vielleicht auch nur für ein paar Minu- benermaßen erst relativ spät entdeckt. Seither ist ständnis. All diese Hieroglyphen und Linea- ten, wieder ins Rampenlicht einstiger Pracht es mir ein Anliegen, „Papa Haydn“ den Zopf abzu- mente, die vom Schreiber X zur Quelle Y, & Herrlichkeit. Wer war denn wohl der Ko- schneiden, den ihm das 19. und 20. Jahrhundert von zweifelhaften Wasserzeichen zu unech- pist, wer waren die fleißigen Leute, die dem haben wachsen lassen. Die Gesamteinspielung der ten Tintensorten führen – diese kryptischen Hofkapellmeister des Fürsten Nikolaus von Haydn-Sinfonien ist für meine Musiker und mich Überlieferungsnachweise und Stammbäume, Eszterházy bei seiner unablässigen Produkti- eine höchst interessante Aufgabe und eine große fachlich korrekter als „Stemmata“ bezeich- on zur Hand gingen? Für wen notierte Herausforderung, bietet sich doch mit diesem ehr- net: Müssen wir uns wirklich jede noch so „Schreiber F“, wenn ihm noch ein paar geizigen Projekt die einmalige Chance, die Ent- hypothetische Frage stellen lassen, ehe uns Nachtstunden blieben, einen zweiten Stim- wicklung der klassischen Sinfonie hautnah nachzu- die Kontaktaufnahme mit dem eigentlichen mensatz? Wie viele Kreutzer mag er dafür erleben. In Zeiten musikalischen (und gesellschaft- Notentext gestattet wird? bekommen, wen davon möglicherweise er- DEUTSCH lichen) Wandels war Haydn Stürmer, Dränger, Das hängt von der eigenen Art der Be- nährt haben? War’s seine Fehlsichtigkeit, Sucher und Finder zugleich. -

Joseph Haydn (1732–1809) Missa in Angustiis – Nelsonmesse (Hob

Joseph Haydn (1732–1809) Missa in Angustiis – Nelsonmesse (Hob. XXII:11) Kirchenmusikalische Kompositionen für liturgische Zwecke, insbesondere zur Ausgestaltung der römisch-katholischen Messe, erscheinen in allen Schaffensphasen von Joseph Haydn: Die Missa brevis in F (Hob. XXII:1) schrieb der junge Haydn um 1749 – das Jahr, in dem er infolge des Stimmbruchs Abschied als Chorknabe am Wiener Stephansdom nehmen musste und in dem für ihn eine beschwerliche Phase als freischaffender Musiker begann. Am Ende dieser Reihe steht die Harmoniemesse (Hob. XXII:14), die erstmals 1802 in der Eisenstädter Bergkirche erklang. Danach war es dem mittlerweile 70-jährigen Haydn körperlich nicht mehr möglich, zu komponieren oder öffentlich aufzutreten. Auffällig sind zwei Lücken (zwischen 1750 und 1766 sowie zwischen 1782 und 1796), in denen kein größeres geistliches Werk entstand. Die zweite Lücke war eine Folge der kirchlichen Reformen von Kaiser Joseph II., die nicht nur zur Auflösung der meisten Klöster in den Ländern der Habsburgermonarchie führten, sondern die Liturgie auch von als überflüssig empfundenen Prunk befreiten. Es wurden zahlreiche Verordnungen erlassen, die unter anderem den Einsatz von orchestraler Musik im Gottesdienst regelten und im Ergebnis einschränkten. Aufträge für solche Kompositionen gingen daher erheblich zurück. Erst als Franz II. 1792 die österreichische Regentschaft übernommen hatte, lockerten sich die Vorschriften wieder. In diese Phase fällt die Entstehung von Haydns sechs späten Messen (die sogenannten Hochämter), darunter die der Nelsonmesse. Sie gehören zu den letzten Werken des Komponisten. Die erwähnte kirchenmusikalische Pause, in die auch die beiden Londoner Aufenthalte fielen, hatte Haydn indes zur Erprobung neuer kompositorischer Techniken in Sinfonien und Kammermusik genutzt. Dies zeigte sich nun beispielsweise in „souveräner Beherrschung der Formgestaltung‟, der Hinwendung zur liedhaften Thematik, der „Verfeinerung des Orchestersatzes‟ sowie im „Trend zu einer deutlichen Individualisierung des Einzelwerks‟. -

Sacred Music, 136.4, Winter 2009

SACRED MUSIC Winter 2009 Volume 136, Number 4 EDITORIAL Viennese Classical Masses? | William Mahrt 3 ARTICLES Between Tradition and Innovation: Sacred Intersections and the Symphonic Impulse in Haydn’s Late Masses | Eftychia Papanikolaou 6 “Requiem per me”: Antonio Salieri’s Plans for His Funeral | Jane Schatkin Hettrick 17 Haydn’s “Nelson” Mass in Recorded Performance: Text and Context | Nancy November 26 Sunday Vespers in the Parish Church | Fr. Eric M. Andersen 33 REPERTORY The Masses of William Byrd | William Mahrt 42 COMMENTARY Seeking the Living: Why Composers Have a Responsibility to be Accessible to the World | Mark Nowakowski 49 The Role of Beauty in the Liturgy | Fr. Franklyn M. McAfee, D.D. 51 Singing in Unison? Selling Chant to the Reluctant Choir | Mary Jane Ballou 54 ARCHIVE The Lost Collection of Chant Cylinders | Fr. Jerome F. Weber 57 The Ageless Story | Jennifer Gregory Miller 62 REVIEWS A Gift to Priests | Rosalind Mohnsen 66 A Collection of Wisdom and Delight | William Tortolano 68 The Fire Burned Hot | Jeffrey Tucker 70 NEWS The Chant Pilgrimage: A Report 74 THE LAST WORD Musical Instruments and the Mass | Kurt Poterack 76 POSTSCRIPT Gregorian Chant: Invention or Restoration? | William Mahrt SACRED MUSIC Formed as a continuation of Caecilia, published by the Society of St. Caecilia since 1874, and The Catholic Choirmaster, published by the Society of St. Gre- gory of America since 1915. Published quarterly by the Church Music Associ- ation of America. Office of Publication: 12421 New Point Drive, Harbour Cove, Richmond, VA 23233. E-mail: [email protected]; Website: www.musicasacra.com Editor: William Mahrt Managing Editor: Jeffrey Tucker Editor-at-Large: Kurt Poterack Editorial Assistance: Janet Gorbitz and David Sullivan. -

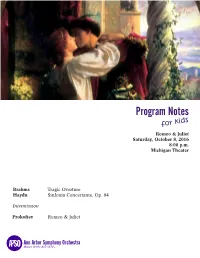

Program Notes

Program Notes for kids Romeo & Juliet Saturday, October 8, 2016 8:00 p.m. Michigan Theater Brahms Tragic Overture Haydn Sinfonia Concertante, Op. 84 Intermission Prokofiev Romeo & Juliet Tragic Overture by Johannes Brahms What kind of piece is this? This piece is a concert overture, similar to the overture of an opera. An opera overture is the opening instrumental movement that signals to the audience that the perfor- mance is about to begin. Similarily, a concert overture is a short and lively introduction to an instrumental con- cert. When was it written? Brahms wrote this piece in the summer of 1880 while on vacation. Brahms at the Piano What is it about? Brahms was a quiet and sad person, and really wanted to compose a piece about a tragedy. With no particular tragedy in mind, he created this overture as a contrast to his much happier Academic Festival Overture, which he completed in the same summer. When describing the two overtures to a friend, Brahms said “One of them weeps, the other laughs.” About the Composer Fun Facts Johannes Brahms | Born May 7, 1833 in Hamburg, Ger- Brahms never really grew up. He didn’t many | Died April 3, 1897 in Vienna, Austria care much about how he looked, he left his clothes lying all over the floor Family & Carfeer of his house, he loved merry-go-rounds and circus sideshows, and he continued Brahms’ father, Johann Jakob Brahms, was a bierfiedler: playing with his childhood toys until he literally, a “beer fiddler” who played in small bands at was almost 30 years old. -

Read Michael Driscoll's Progam Notes

FROM THE MUSIC DIRECTOR The idea for this program began with Haydn’s Missa in angustiis, which roughly translates as “Mass for Troubled Times.” The exact reasons why Haydn titled this Mass as being for “troubled times” are not known for sure, but scholars have suggested several possible reasons for this particular title. One is that Haydn, by then in his mid‐ 60s, had recently been quite ill. Another is that he had to compose the Mass in a short six‐week period. A third possibility is that the usual orchestral forces available to him were restricted because his patron, Nikolaus II, was experiencing financial troubles as a result of political and financial instability in Europe. Related to that, Napoleon and the French were threatening Austria yet again. Perhaps it was a combination of all of these factors that prompted Haydn to label the work “in angustiis.” (The work later also became popularly known as the “Lord Nelson Mass,” though the reason for this association is not entirely clear.) Once I settled on the Haydn Mass, I began thinking about other works which might complement it. I eventually discovered David Conte’s September Sun, a work written in memory of those who perished on September 11, 2001. September Sun depicts the chaos of that dreadful day before concluding on an elegiac tone. Given the conflict inherent in both the Haydn and Conte works, I wanted to end the concert on a more optimistic note, and so I added Mack Wilberg’s arrangement of the African‐American spiritual Peace Like a River. -

A Form-Functional Approach to Haydn's Theresienmesse

HAYDN: The Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America Volume 10 Number 1 Spring 2020 Article 2 March 2020 The Kyrie as Sonata Form: A Form-Functional Approach to Haydn's Theresienmesse Halvor K. Hosar Follow this and additional works at: https://remix.berklee.edu/haydn-journal Recommended Citation Hosar, Halvor K. (2020) "The Kyrie as Sonata Form: A Form-Functional Approach to Haydn's Theresienmesse," HAYDN: The Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America: Vol. 10 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://remix.berklee.edu/haydn-journal/vol10/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Research Media and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in HAYDN: The Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America by an authorized editor of Research Media and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Hosar, Halvor K. “The Kyrie as Sonata Form: A Form-Functional Approach to Haydn’s Theresienmesse.” HAYDN: Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America 10.1 (Spring 2020), http://haydnjournal.org. © RIT Press and Haydn Society of North America, 2020. Duplication without the express permission of the author, RIT Press, and/or the Haydn Society of North America is prohibited. The Kyrie as Sonata Form: A Form-Functional Approach to Haydn’s Theresienmesse1 By Halvor K. Hosar I. Introduction The theories of William Caplin, James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy have done much to revitalize the dormant Formenlehre tradition, by devising new analytical -

Mariazellermesse Paukenmesse

HAYDN Mariazellermesse Missa Cellensis Paukenmesse Missa in tempore belli (‘Mass in Time of War’) Trinity Choir • REBEL Baroque Orchestra J. Owen Burdick 8.572124 Haydn masses-Mariazellermesse booklet.indd 1 15/2/10 15:57:27 Joseph HAYDN (1732–1809) Missa Cellensis, ‘Mariazellermesse’ 34:03 in C major (Hob.XXII:8; 1782) 1 Kyrie 1 4:24 2 Gloria 1:44 3 Gratias agimus tibi 2 5:14 4 Quoniam tu solus sanctus 1:53 5 Credo 1:35 6 Et incarnatus est 4:29 7 Et resurrexit 0:57 8 Et vitam venturi 1:20 9 Sanctus 2:29 0 Benedictus 1 5:15 ! Agnus Dei 2:28 @ Dona nobis pacem 2:15 Ann Hoyt, soprano 1 • Sharla Nafziger, soprano 2 Kirsten Sollek, alto • Nathan Davis, tenor Richard Lippold, bass Trinity Choir Rebel Baroque Orchestra Jörg Michael Schwarz, leader J. Owen Burdick 8.572124 2 8.572124 Haydn masses-Mariazellermesse booklet.indd 2 15/2/10 15:57:28 Joseph HAYDN (1732–1809) Missa Cellensis, ‘Mariazellermesse’ 34:03 Missa in tempore belli, ‘Paukenmesse’ 37:34 in C major in C major (Hob.XXII:8; 1782) (Hob.XXII:9; 1796) 1 1 Kyrie 4:24 # Kyrie 4:29 2 $ Gloria 1:44 Gloria 2:49 2 3 Gratias agimus tibi 5:14 % Qui tollis peccata mundi 4:46 4 Quoniam tu solus sanctus 1:53 ^ Quoniam tu solus sanctus 2:26 5 Credo 1:35 & Credo 1:13 6 Et incarnatus est 4:29 * Et incarnatus est 3:31 7 Et resurrexit 0:57 ( Et resurrexit 2:04 8 Et vitam venturi 1:20 ) Et vitam venturi 2:25 9 ¡ Sanctus 2:29 Sanctus 2:05 1 0 Benedictus 5:15 ™ Benedictus 5:56 ! Agnus Dei 2:28 £ Agnus Dei 2:47 @ Dona nobis pacem 2:15 ¢ Dona nobis pacem 3:03 Ann Hoyt, soprano 1 • Sharla Nafziger, soprano 2 Ann Hoyt, soprano • Kirsten Sollek, alto Kirsten Sollek, alto • Nathan Davis, tenor Daniel Neer, tenor • Richard Lippold, bass Richard Lippold, bass Trinity Choir Trinity Choir Rebel Baroque Orchestra Rebel Baroque Orchestra Jörg Michael Schwarz, leader Jörg Michael Schwarz, leader J. -

JEFFREY THOMAS Music Director

support materials for our recording of JOSEPH HAYDN (732-809): MASSES Tamara Matthews soprano - Zoila Muñoz alto Benjamin Butterfield tenor - David Arnold bass AMERICAN BACH SOLOISTS AMERICAN BACH CHOIR • PACIFIC MOZART ENSEMBLE Jeffrey Thomas, conductor JEFFREY THOMAS music director Missa in Angustiis — “Lord Nelson Mass” soprano soloist’s petition “Suscipe” (“Receive”) is followed by the unison choral response “deprecationem nostram” (“our Following the extraordinary success of his two so- prayer”). journs in London, Haydn returned in 1795 to his work as Kapellmeister for Prince Nikolas Esterházy the younger. The Even in the traditionally upbeat sections of the liturgy, Prince wanted Haydn to re-establish the Esterházy orchestra, the frequent turns to minor harmonies invoke the upheaval disbanded by his unmusical father, Prince Anton. Haydn’s re- wrought by war and disallow a sense of emotional—and au- turn to active duty for the Esterházy family did not, however, ditory—complacency. After the optimistic D-major opening signify a return to the isolated and static atmosphere of the of the Gloria, for example, the music slips into E minor at the relatively remote Esterházy palace, which had been given up words “et in terra pax hominibus” (“and peace to His people after the elder Prince Nikolas’s death in 1790. Haydn was now on earth”); throughout the section, D-minor inflections cloud able to work at the Prince’s residence in Vienna for most of the laudatory mood of the first theme and the text in general. the year, retiring to the courtly lodgings at Eisenstadt during The Benedictus is even more startling. -

Accepted Faculty of Graduate Studies

ACCEPTED FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES JOSEPH HAYDN AND THE DRAMMA GIOCOSO by Patricia Anne Debly Mus.Bac., University of Western Ontario, 1978 M.Mus., Catholic University of America, 1980 M.A., University of Victoria, 1985 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the School of Music We accept this dissertation as conforming to the required standard I^an G. Lazarevich, Supervisor (Faculty of Graduate Studies) Dr. E. Schwandt, Departmental Member (School of Music] Dr. A. Q^fghes, Outside Member (Theatre Department) Dr. J. ..ujiey-r-Outside (History Department) Dr. M. Tér^-Smith, External Examiner (Music Department, Western Washington University) © PATRICIA ANNE DEBLY, 1993 University of Victoria All rights reserved. Dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopying or other means, without the permission of the author. 11 Supervisor; Dean Gordana Lazarevich ABSTRACT Haydn's thirteen extant Esterhdzy operas, composed from 1762-85, represent a microcosm of the various trends in Italian opera during the eighteenth century'. His early operas illustrate his understanding and mastery of the opera seria, the intermezzo and the opera buffa traditions which he would utilize in his later draimi giocosi. In addition to his role as Kapellmeister Haydn adcpted and conducted over eighty-one operas by the leading Italian composers of his day, resulting in over 1,026 operatic performances for the period between 1780-90 alone and furthering his knowledge of the latest styles in Italian opera. This dissertation examines the five draimi giocosi which Haydn wrote, beginning with Le pescatrici {1769) through to La fedelta preiniata (1780), within the context of the draima giocoso tradition. -

Joseph Haydn, Op 76 No 5 in D Major Transcript

Joseph Haydn, Op 76 No 5 in D major Transcript Date: Thursday, 18 March 2010 - 12:00AM Location: Museum of London Haydn: Quartet Op. 76 No. 5 Professor Roger Parker 18/3/2010 Today's lecture is about Haydn's Op. 76 No. 5, and with it we come to the last of our three Haydn string quartets, all of them from the Op. 76 collection. In the last lecture, on Op. 76 No. 2, I mentioned something about how Haydn had fared in the two centuries since he wrote these marvellous quartets: how writers and listeners had, during those two centuries, tried to come to terms with him and his music; and also how that coming-to-terms changed with the changing times. For the nineteenth century, that great age of biography, the efforts were hampered by difficulties over what we might (anachronistically) call Haydn's "personality", an area that proved hard to grasp for Romantic sensibilities. While it was easy to paint seductive pictures of bewigged Mozart as the eternal child-genius, and of bad-hair-day Beethoven as titanic and sublime, Haydn seemed, in this period at least, close to being a Man Without Qualities. It was already well known, after all, that for most of his life he had been little more than a loyal servant in an aristocratic household (that of the fabulously wealthy Esterhazy family). When public fame came in the 1790s of Paris and London, he was elderly by the standards of the day...almost a relic from another age. And so the figure emerged of "Papa" Haydn: not a stern patriarch, but something much more homely: the composer of repertoire choral works and a few symphonies and quartets; the man who made the eternal Mozart and the sublime Beethoven possible, but who in the process seemed to fade into the shadows. -

Sacred Music Volume 109 Number 4

SACRED MUSIC Volume 109, Number 4, 1982 Eisenstadt Palace, garden front. SACRED MUSIC Volume 109, Number 4, 1982 FROM THE EDITORS Haydn in Vienna: the Late Years (1795-1809) Archbishop Weakland Cardinal Bernadin Music in our Church Schools WHY HAYDN WROTE HIS CHURCH MUSIC Otto Biba A LATIN HIGH MASS IN UPPER MICHIGAN Milton Olsson 11 Charles Nelson A CHRONICLE OF THE REFORM Part IV: Musicam sacrum 15 Monsignor Richard ). Schuler REVIEWS 22 NEWS 25 EDITORIAL NOTES 26 CONTRIBUTORS 27 INDEX TO VOLUME 109 28 SACRED MUSIC Continuation of Caecilia, published by the Society of St. Caecilia since 1874, and The Catholic Choirmaster, published by the Society of St. Gregory of America since 1915. Published quarterly by the Church Music Association of America. Office of publications: 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103. Editorial Board: Rev. Msgr. Richard J. Schuler, Editor Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O. Cist. Rev. John Buchanan Harold Hughesdon William P. Mahrt Virginia A. Schubert Cal Stepan Rev. Richard M. Hogan Mary Ellen Strapp Judy Labon News: Rev. Msgr. Richard J. Schuler 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103 Music for Review: Paul Salamunovich, 10828 Valley Spring Lane, N. Hollywood, Calif. 91602 Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O. Cist., Eintrachstrasse 166, D-5000 Koln 1, West Germany Paul Manz, 7204 Schey Drive, Edina, Minnesota 55435 Membership, Circulation and Advertising: 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103 CHURCH MUSIC ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Officers and Board of Directors President Monsignor Richard J. Schuler Vice-President Gerhard Track General Secretary Virginia A. Schubert Treasurer Earl D. Hogan Directors Mrs.