The Seven Last Words Project Cathedral of St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music Making Politics: Beyond Lyrics

Politik Nummer 1 | Årgang 23 | 2020 Music making politics: beyond lyrics M.I. Franklin, Professor of Global Media and Politics, Goldsmiths University of London In this article I argue that considering how any sort of music is made more closely - as sonic material, performance cultures, for whom and on whose terms, is integral to pro- jects exploring the music-politics nexus. The case in point is “My Way”, a seemingly apo- litical song, as it becomes repurposed: transformed through modes of performance, unu- sual musical arrangements, and performance contexts. The analysis reveals a deeper, underlying politics of music-making that still needs unpacking: the race, gender, and class dichotomies permeating macro- and micro-level explorations into the links between music, society, and politics. Incorporating a socio-musicological analytical framework that pays attention to how this song works musically, alongside how it can be reshaped through radical performance and production practices, shows how artists in diverging contexts can ‘re-music’ even the most hackneyed song into a form of political engage- ment. Introduction In 2016, Bob Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. In 2018 Kendrick Lamar became the first Rap artist to win the Pulitzer Prize for Music. Between these two medi- atized moments of public recognition, across the race and genre divides of contemporary culture lie many musico-political timelines, recording careers, playlists, and embodied musicalities. This article aims to show why, and how theory and research into the rela- tionship between (the study of) politics and music-making need to move beyond indica- tors of political relevance that are based on lyrics, an artist’s public persona, public profile or critical acclaim. -

4474134-09A1a4-Booklet-CD98.626

2.K ach intensiver Auseinandersetzung mit dem er „kritische Bericht“, dieser Inbegriff Symbole werden zu Akteuren eines unserer Nsinfonischen Werk Mozarts und Beethovens Dgeduldigsten Forscherfleißes, begegnet Imagination entspringenden Theaters und habe ich meine Liebe zu Haydns Musik zugege- abseits seines Fachbezirks vielfachem Unver- treten, vielleicht auch nur für ein paar Minu- benermaßen erst relativ spät entdeckt. Seither ist ständnis. All diese Hieroglyphen und Linea- ten, wieder ins Rampenlicht einstiger Pracht es mir ein Anliegen, „Papa Haydn“ den Zopf abzu- mente, die vom Schreiber X zur Quelle Y, & Herrlichkeit. Wer war denn wohl der Ko- schneiden, den ihm das 19. und 20. Jahrhundert von zweifelhaften Wasserzeichen zu unech- pist, wer waren die fleißigen Leute, die dem haben wachsen lassen. Die Gesamteinspielung der ten Tintensorten führen – diese kryptischen Hofkapellmeister des Fürsten Nikolaus von Haydn-Sinfonien ist für meine Musiker und mich Überlieferungsnachweise und Stammbäume, Eszterházy bei seiner unablässigen Produkti- eine höchst interessante Aufgabe und eine große fachlich korrekter als „Stemmata“ bezeich- on zur Hand gingen? Für wen notierte Herausforderung, bietet sich doch mit diesem ehr- net: Müssen wir uns wirklich jede noch so „Schreiber F“, wenn ihm noch ein paar geizigen Projekt die einmalige Chance, die Ent- hypothetische Frage stellen lassen, ehe uns Nachtstunden blieben, einen zweiten Stim- wicklung der klassischen Sinfonie hautnah nachzu- die Kontaktaufnahme mit dem eigentlichen mensatz? Wie viele Kreutzer mag er dafür erleben. In Zeiten musikalischen (und gesellschaft- Notentext gestattet wird? bekommen, wen davon möglicherweise er- DEUTSCH lichen) Wandels war Haydn Stürmer, Dränger, Das hängt von der eigenen Art der Be- nährt haben? War’s seine Fehlsichtigkeit, Sucher und Finder zugleich. -

Short Version

Wynton Marsalis Wynton assembled his own band in 1981 and hit the road, performing over 120 concerts every year for 15 consecutive years. With the power of his superior musicianship, the infectious sound of his swinging bands and an exhaustive series of performances and music workshops, Marsalis rekindled widespread interest in jazz throughout the world. Students of Marsalis’ workshops include: James Carter, Christian McBride, Roy Hargrove, Harry Connick Jr., Nicholas Payton, Eric Reed and Eric Lewis, to name a few. Classical Career At the age of 20, Wynton recorded the Haydn, Hummel and Leopold Mozart trumpet concertos. His debut recording received glorious reviews and won the Grammy Award® for “Best Classical Soloist with an Orchestra.” Marsalis went on to record 10 additional classical records, all to critical acclaim. Wynton performed with leading orchestras including the New York Philharmonic, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Boston Pops, The Cleveland Orchestra, Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra, ynton Marsalis is an internationally acclaimed English Chamber Orchestra, Toronto Symphony Orchestra and musician, composer, bandleader, educator and a London’s Royal Philharmonic, working with an eminent group of Wleading advocate of American culture. He is the conductors including: Leppard, Dutoit, Maazel, Slatkin, Salonen world’s first jazz artist to perform and compose across the full and Tilson-Thomas. Famed classical trumpeter Maurice André jazz spectrum from its New Orleans roots to bebop to modern praised Wynton as “potentially the greatest trumpeter of all jazz. By creating and performing an expansive range of brilliant time.” new music for quartets to big bands, chamber music ensembles to symphony orchestras, tap dance to ballet, Wynton has The Composer expanded the vocabulary for jazz and created a vital body of To date Wynton has produced over 70 records which have work that places him among the world’s finest musicians and sold over seven million copies worldwide including three Gold composers. -

Woodrow Wilson Fellows-Pulitzer Prize Winners

Woodrow Wilson Fellows—Pulitzer Prize Winners last updated January 2014 Visit http://woodrow.org/about/fellows/ to learn more about our Fellows. David W. Del Tredici Recipient of the 1980 Pulitzer Prize for Music In Memory of a Summer Day Distinguished Professor of Music • The City College of New York 1959 Woodrow Wilson Fellow Caroline M. Elkins Recipient of the 2006 Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction Imperial Reckoning: The Untold Story of Britain's Gulag in Kenya (Henry Holt) Professor of History • Harvard University 1994 Mellon Fellow Joseph J. Ellis, III Recipient of the 2001Pulitzer Prize for History Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation (Alfred A. Knopf) Professor Emeritus of History • Mount Holyoke College 1965 Woodrow Wilson Fellow Eric Foner Recipient of the 2011Pulitzer Prize for History The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (W.W. Norton) DeWitt Clinton Professor of History • Columbia University 1963 Woodrow Wilson Fellow (Hon.) Doris Kearns Goodwin Recipient of the 1995 Pulitzer Prize for History No Ordinary Time: Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II (Simon & Schuster) Historian 1964 Woodrow Wilson Fellow Stephen Greenblatt Recipient of the 2012 Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction The Swerve: How the World Became Modern (W.W. Norton) Cogan University Professor of the Humanities • Harvard University 1964 Woodrow Wilson Fellow (Hon.) Robert Hass Recipient of one of two 2008 Pulitzer Prizes for Poetry Time and Materials (Ecco/HarperCollins) Distinguished Professor in Poetry and Poetics • The University of California at Berkeley 1963 Woodrow Wilson Fellow Michael Kammen (deceased) Recipient of the 1973 Pulitzer Prize for History People of Paradox: An Inquiry Concerning the Origins of American Civilization (Alfred A. -

American Composers Orchestra Presents Next Composer to Composer Talks in January

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Contact: Christina Jensen, Jensen Artists 646.536.7864 x1 [email protected] American Composers Orchestra Presents Next Composer to Composer Talks in January William Bolcom & Gabriela Lena Frank Wednesday, January 13, 2021 at 5pm ET – Online Registration & Information: http://bit.ly/ComposerToComposerBolcom John Corigliano & Mason Bates Wednesday, January 27, 2021 at 5pm ET – Online Registration & Information: http://bit.ly/ComposerToComposerCorigliano Free, registration recommended. New York, NY – American Composers Orchestra (ACO) presents its next Composer to Composer Talks online in January, with composers William Bolcom and Gabriela Lena Frank on Wednesday, January 13, 2021 at 5pm ET, and John Corigliano and Mason Bates on Wednesday, January 27, 2021 at 5pm ET. The talks will be live-streamed and available for on-demand viewing for seven days. Tickets are free; registration is highly encouraged. Registrants will receive links to recordings of featured works in advance of the event. ACO’s Composer to Composer series features major American composers in conversation with each other about their work and leading a creative life. The intergenerational discussions begin by exploring a single orchestral piece, with one composer interviewing the other. Attendees will gain insight into the work’s genesis, sound, influence on the American orchestral canon, and will be invited to ask questions of the artists. On January 13, Gabriela Lena Frank talks with William Bolcom about his Symphony No. 9, from 2012, of which Bolcom writes, “Today our greatest enemy is our inability to listen to each other, which seems to worsen with time. All we hear now is shouting, and nobody is listening because the din is so great. -

Program Notes

Program Notes for kids Romeo & Juliet Saturday, October 8, 2016 8:00 p.m. Michigan Theater Brahms Tragic Overture Haydn Sinfonia Concertante, Op. 84 Intermission Prokofiev Romeo & Juliet Tragic Overture by Johannes Brahms What kind of piece is this? This piece is a concert overture, similar to the overture of an opera. An opera overture is the opening instrumental movement that signals to the audience that the perfor- mance is about to begin. Similarily, a concert overture is a short and lively introduction to an instrumental con- cert. When was it written? Brahms wrote this piece in the summer of 1880 while on vacation. Brahms at the Piano What is it about? Brahms was a quiet and sad person, and really wanted to compose a piece about a tragedy. With no particular tragedy in mind, he created this overture as a contrast to his much happier Academic Festival Overture, which he completed in the same summer. When describing the two overtures to a friend, Brahms said “One of them weeps, the other laughs.” About the Composer Fun Facts Johannes Brahms | Born May 7, 1833 in Hamburg, Ger- Brahms never really grew up. He didn’t many | Died April 3, 1897 in Vienna, Austria care much about how he looked, he left his clothes lying all over the floor Family & Carfeer of his house, he loved merry-go-rounds and circus sideshows, and he continued Brahms’ father, Johann Jakob Brahms, was a bierfiedler: playing with his childhood toys until he literally, a “beer fiddler” who played in small bands at was almost 30 years old. -

Program Notes

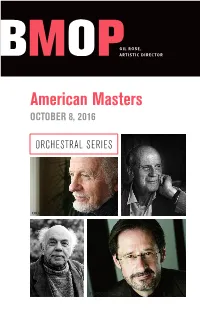

GIL ROSE, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR ORCHESTRAL SERIES COLGRASS KUBIK SHAPERO STUCKY BMOP2016 | 2017 JORDAN HALL AT NEW ENGLAND CONSERVATORY coming up next: The Picture of Dorian Gray friday, november 18 — 8pm IN COLLABORATION WITH ODYSSEY OPERA American Masters “Pleasures secret and subtle, wild joys and wilder sins…” SATURDAY OCTOBER 8, 2016 8:00 BMOP and Odyssey Opera bring to life Lowell Liebermann’s operatic version of Oscar Wilde’s classic horror novel in a semi-staged production. Glass Works saturday, february 18 — 8pm CELEBRATING THE ARTISTRY OF PHILIP GLASS BMOP salutes the influential minimalist pioneer with a performance of his Symphony No. 2 and other works, plus the winner of the annual BMOP-NEC Composition Competition. Boston Accent friday, march 31 — 8pm sunday, april 2 — 3pm [amherst college] Four distinctive composers, Bostonians and ex-Bostonians, represent the richness of our city’s musical life. Featuring David Sanford’s Black Noise; John Harbison’s Double Concerto for violin, cello, and orchestra; Eric Sawyer’s Fantasy Concerto: Concord Conversations, and Ronald Perera’s The Saints. As the Spirit Moves saturday, april 22 — 8pm [sanders theatre] FEATURING THE HARVARD CHORUSES, ANDREW CLARK, DIRECTOR Two profound works from either side of the ocean share common themes of struggle and transcendence: Trevor Weston’s Griot Legacies and Michael Tippett’s A Child of Our Time. BOSTON MODERN ORCHESTRA PROJECT | 781.324.0396 | BMOP.org American Masters SATURDAY OCTOBER 8, 2016 8:00 JORDAN HALL AT NEW ENGLAND CONSERVATORY Pre-concert talk by Robert Kirzinger at 7:00 MICHAEL COLGRASS The Schubert Birds (1989) GAIL KUBIK Symphony Concertante (1952) I. -

The Pulitzer Prize for Music It’S Time to Alter and Affirm

The Pulitzer Prize for Music It’s Time to Alter and Affirm A statement by the Pulitzer Prize Board, June 1, 2004 The variety, vitality and creativity of high-quality American music today make the Pulitzer Prize for Music more important than ever. After more than a year of studying the Prize, now in its 61st year, the Pulitzer Prize Board declares its strong desire to consider and honor the full range of distinguished American musical compositions – from the contemporary classical symphony to jazz, opera, choral, musical theater, movie scores and other forms of musical excellence. The Board also notes that many composers move among those various forms and that the Music Prize competition should reflect that artistic richness. Accordingly, without seeking to favor any particular form of music, the Board announces the following changes in the Music Prize, effective with the 2005 competition: First, the definition of the Prize will be revised to encourage greater diversity in entries while assuring even-handed evaluation of compositions. Currently, the definition reads: “For distinguished musical composition of significant dimension by an American that has had its first performance in the United States during the year.” The new definition reads: “For a distinguished musical composition by an American that has had its first performance or recording in the United States during the year.” The revised definition adopts a broad view of serious music. Thus, the definition drops the words “significant dimension” in relation to a composition because the words might have limited entries by applicants or limited the evaluations by jurors. The definition also accepts the public release of a recording as the equivalent of a public performance, which will widen the prize’s reach. -

Scott Davie (How Kendrick Lamar's Pulitzer Prize Win...)

URL: https://theconversation.com/how-kendrick-lamars-pulitzer-win-blurs-lines-between- classical-music-and-pop-95213 How Kendrick Lamar’s Pulitzer win blurs lines between classical music and pop April 24, 2018 6.09am AEST Author 1. Scott Davie Piano tutor and Lecturer, Sydney Conservatorium Music, University of Sydney Disclosure statement Scott Davie does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment. Partners The awarding of the 2018 Pulitzer Music Prize to Kendrick Lamar for his album DAMN. has attracted considerable controversy. The American rapper edged out the young Michael Gilbertson, who wrote a string quartet in a traditional format, and Ted Hearne, who created a modernist setting of a contemporary text for voices, electric guitars and percussion. Some have read the decision as a sign of low art (music designed for popular consumption, often with an eye on financial reward) vanquishing high art (esoteric music of transcendent purpose.) Yet to argue this is to prejudice Lamar on the basis of the style of his music. Like Lamar’s previous albums, the music of DAMN. is effortlessly creative, with constant attention to shadings of mood and beat. There are many contributors, in the fields of production, vocals and sampling, and the timing throughout is both artful and innovative. As a personally-lived document of life for black Americans today, DAMN. is unique. Yet to some critics, the decision elevates a form of music that has no place among the esteemed offerings of past recipients (which historically has included some of America’s pre-eminent composers in the European art- music tradition). -

Aaron Jay Kernis.” – Forbes

“In the 20th century there were giants in the land. Charles Ives, Duke Ellington, George Gershwin, Aaron Copland, and Leonard Bernstein. But who is filling those shoes now? Heading many lists is Aaron Jay Kernis.” – Forbes Winner of the coveted 2002 Grawemeyer Award for Music Composition and one of the youngest composers ever to be awarded the Pulitzer Prize, AARON JAY KERNIS is among the most esteemed musical figures of his generation. With "fearless originality [and] powerful voice" (The New York Times), each new Kernis work is eagerly awaited by audiences and musicians alike, and he is one of today's most frequently performed composers. His music, full of variety and dynamic energy, is rich in lyric beauty, poetic imagery, and brilliant instrumental color. His works figure prominently on orchestral, chamber, and recital programs world-wide and have been commissioned by many of America‘s foremost performers, including sopranos Renee Fleming and Dawn Upshaw, violinists Joshua Bell, Pamela Frank, Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg and James Ehnes (for the BBC Proms), pianist Christopher O'Riley and guitarist Sharon Isbin, and such musical institutions as the New York Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra (for the inauguration of its new home at the Kimmel Center), Walt Disney Company, Rose Center for Earth and Space at New York’s American Museum of Natural History, Ravinia Festival (for James Conlon’s inaugural season), San Francisco and Singapore Symphonies, Minnesota Orchestra, Lincoln Center Great Performers Series, American Public Radio; Los Angeles and Saint Paul Chamber Orchestras, and Aspen Music Festival and programs from Philadelphia to Amsterdam (Concertgebouw, Amsterdam Sinfonietta), Santa Barbara to France (Orchestra National De France) throughout Europe and beyond. -

News Release

news release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PRESS CONTACT: Maggie Stapleton, Jensen Artists September 25, 2019 646.536.7864 x2; [email protected] American Composers Orchestra Announces 2019-2020 Season Derek Bermel, Artistic Director & George Manahan, Music Director Two Concerts presented by Carnegie Hall New England Echoes on November 13, 2019 & The Natural Order on April 2, 2020 at Zankel Hall Premieres by Mark Adamo, John Luther Adams, Matthew Aucoin, Hilary Purrington, & Nina C. Young Featuring soloists Jamie Barton, mezzo-soprano; JIJI, guitar; David Tinervia, baritone & Jeffrey Zeigler, cello The 29th Annual Underwood New Music Readings March 12 & 13, 2020 at Aaron Davis Hall at The City College of New York ACO’s annual roundup of the country’s brightest young and emerging composers EarShot Readings January 28 & 29, 2020 with Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra May 5 & 6, 2020 with Houston Symphony Third Annual Commission Club with composer Mark Adamo to support the creation of Last Year ACO Gala 2020 honoring Anthony Roth Constanzo, Jesse Rosen, & Yolanda Wyns March 4, 2020 at Bryant Park Grill www.americancomposers.org New York, NY – American Composers Orchestra (ACO) announces its full 2019-2020 season of performances and engagements, under the leadership of Artistic Director Derek Bermel, Music Director George Manahan, and President Edward Yim. ACO continues its commitment to the creation, performance, preservation, and promotion of music by 1 American Composers Orchestra – 2019-2020 Season Overview American composers with programming that sparks curiosity and reflects geographic, stylistic, racial and gender diversity. ACO’s concerts at Carnegie Hall on November 13, 2019 and April 2, 2020 include major premieres by 2015 Rome Prize winner Mark Adamo, 2014 Pulitzer Prize winner John Luther Adams, 2018 MacArthur Fellow Matthew Aucoin, 2017 ACO Underwood Commission winner Hilary Purrington, and 2013 ACO Underwood Audience Choice Award winner Nina C. -

2020/21 Season Join Music Director Jaap Van Zweden and Your Orchestra for the 2020/21 Season

2020/21 SEASON JOIN MUSIC DIRECTOR JAAP VAN ZWEDEN AND YOUR ORCHESTRA FOR THE 2020/21 SEASON. 04 08 10 14 16 18 20 21 22 23 Season Special Curated Curated Curated Curated Matinees Young Membership Subscribe Highlights Events Weekday Thursday Friday Saturday People’s Sampler Series Evening Series Evening Series Evening Series Concerts® GYÖRGY KURTÁG | SAMUEL BECKETT FIN DE PARTIE “Nothing is funnier than unhappiness.” In the dystopian world of Beckett’s Fin de partie (Endgame), we see a blind man, his helpless parents, and his hapless servant bumble and bicker as they wait for an end to their suffering — like four final pieces on a chessboard, waiting for the game to end. Kurtág’s music provides the timeless continuum for the eternal question, one that concerns us in the 21st century now more than ever: how will this universal game play out? The New York Philharmonic presents the US Premiere of Kurtág’s opera based on Beckett’s SEASON TWO tragicomedy in a fully staged production directed by Claire van Kampen (Farinelli and the King) PROJECT 19 and conducted by Jaap van Zweden. 19 Commissions To Celebrate the Centennial of the 19th Amendment nyphil.org/findepartie American women gained the right to vote with the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920. The New York Philharmonic is marking the centennial with Project 19, a multi-season initiative to commission and premiere 19 new works by ARTIST-IN-RESIDENCE women, launched last season. The single largest women-only commissioning initiative in history, Project 19 continues in 2020–21. CHICK COREA TAKEOVER Like Mozart, Chick Corea improvises the Unsuk Chin Ellen Reid cadenzas whenever he plays a Mozart piano Mary Kouyoumdjian Maria Schneider ROOMFUL OF TEETH concerto.