Composer of the Month Units for Fifth and Sixth Grade Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SEM Newsletter Ethnomusicology Volume 51, Number 3 Summer 2017

the society for SEM Newsletter ethnomusicology Volume 51, Number 3 Summer 2017 Music, Social Justice, and Resistance Jeffrey A. Summit, Research Professor, Tufts University Department of Music n 5-7 May 2017, a group of colleagues held a confer- this conference as a way to launch projects that would Oence entitled Music, Social Justice, and Resistance engage additional colleagues and work with established in Tiverton, RI. The conference, organized by Jeffrey A. initiatives and interest groups committed to the role of Summit (Tufts University) and sponsored by The Depart- music in social justice and advocacy. Funding and space ment of Music, Tufts University and The Tufts Jonathan constraints limited participation in this initial gathering and M. Tisch College of Civic Life, was hosted and funded by we welcome the future involvement of our colleagues who philanthropists and activists Dr. Michael and Karen Roth- are committed to these issues and already engaged in man. This meeting’s framing impactful projects, nation- question was “Taking into ally and globally. account the current politi- Coming out of this meet- cal direction in our country, ing, we see opportunities and rising authoritarian to expand and deepen tendencies globally, how can national and international we—as musicians, activists, engagement with music and scholars—leverage our and social justice by work- research, teaching, per- ing within the established formance, and activism to structures of academic develop and intensify social and professional organiza- justice initiatives with local tions. An important goal of and global impact?” our retreat was to begin This small gathering of discussing and develop- seventeen colleagues, musi- ing projects that could cians, and activists had am- have a significant national bitious goals. -

An Approach to the Pedagogy of Beginning Music Composition: Teaching Understanding and Realization of the First Steps in Composing Music

AN APPROACH TO THE PEDAGOGY OF BEGINNING MUSIC COMPOSITION: TEACHING UNDERSTANDING AND REALIZATION OF THE FIRST STEPS IN COMPOSING MUSIC DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Vera D. Stanojevic, Graduate Diploma, Tchaikovsky Conservatory ***** The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee: Approved By Professor Donald Harris, Adviser __________________________ Professor Patricia Flowers Adviser Professor Edward Adelson School of Music Copyright by Vera D. Stanojevic 2004 ABSTRACT Conducting a first course in music composition in a classroom setting is one of the most difficult tasks a composer/teacher faces. Such a course is much more effective when the basic elements of compositional technique are shown, as much as possible, to be universally applicable, regardless of style. When students begin to see these topics in a broader perspective and understand the roots, dynamic behaviors, and the general nature of the different elements and functions in music, they begin to treat them as open models for individual interpretation, and become much more free in dealing with them expressively. This document is not designed as a textbook, but rather as a resource for the teacher of a beginning college undergraduate course in composition. The Introduction offers some perspectives on teaching composition in the contemporary musical setting influenced by fast access to information, popular culture, and globalization. In terms of breadth, the text reflects the author’s general methodology in leading students from basic exercises in which they learn to think compositionally, to the writing of a first composition for solo instrument. -

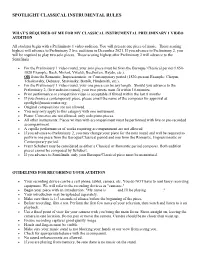

Spotlight Classical Instrumental Rules

SPOTLIGHT CLASSICAL INSTRUMENTAL RULES WHAT’S REQUIRED OF ME FOR MY CLASSICAL INSTRUMENTAL PRELIMINARY 1 VIDEO AUDITION All students begin with a Preliminary 1 video audition. You will present one piece of music. Those scoring highest will advance to Preliminary 2 live auditions in December 2021. If you advance to Preliminary 2, you will be required to play two solo pieces. Those scoring highest after Preliminary 2 will advance to the Semifinals • For the Preliminary 1 video round, your solo piece must be from the Baroque/ Classical period (1650- 1820 Example: Bach, Mozart, Vivaldi, Beethoven, Haydn, etc.). OR from the Romantic, Impressionistic, or Contemporary period (1820-present Example: Chopin, Tchaikovsky, Debussy, Stravinsky, Bartók, Hindemith, etc.). • For the Preliminary 1 video round, your one piece can be any length. Should you advance to the Preliminary 2, (live audition round), your two pieces must fit within 10-minutes. • Prior performance or competition video is acceptable if filmed within the last 8 months • If you choose a contemporary piece, please email the name of the composer for approval at [email protected]. • Original compositions are not allowed. • You may only apply to this category with one instrument. • Piano: Concertos are not allowed; only solo piano pieces. • All other instruments: Pieces written with accompaniment must be performed with live or pre-recorded accompaniment. • A capella performances of works requiring accompaniment are not allowed. • If you advance to Preliminary 2, you may change your piece for the next round and will be required to perform one piece from the Baroque/Classical period and one from the Romantic, Impressionistic or Contemporary period. -

The Fall of Satan in the Thought of St. Ephrem and John Milton

Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies, Vol. 3.1, 3–27 © 2000 [2010] by Beth Mardutho: The Syriac Institute and Gorgias Press THE FALL OF SATAN IN THE THOUGHT OF ST. EPHREM AND JOHN MILTON GARY A. ANDERSON HARVARD DIVINITY SCHOOL CAMBRIDGE, MA USA ABSTRACT In the Life of Adam and Eve, Satan “the first-born” refused to venerate Adam, the “latter-born.” Later writers had difficulty with the tale because it granted Adam honors that were proper to Christ (Philippians 2:10, “at the name of Jesus, every knee should bend.”) The tale of Satan’s fall was then altered to reflect this Christological sensibility. Milton created a story of Christ’s elevation prior to the creation of man. Ephrem, on the other hand, moved the story to Holy Saturday. In Hades, Death acknowledged Christ as the true first- born whereas Satan rejected any such acclamation. [1] For some time I have pondered the problem of Satan’s fall in early Jewish and Christian sources. My point of origin has been the justly famous account found in the Life of Adam and Eve (hereafter: Life).1 1 See G. Anderson, “The Exaltation of Adam and the Fall of Satan,” Journal of Jewish Thought and Philosophy, 6 (1997): 105–34. 3 4 Gary A. Anderson I say justly famous because the Life itself existed in six versions- Greek, Latin, Armenian, Georgian, Slavonic, and Coptic (now extant only in fragments)-yet the tradition that the Life drew on is present in numerous other documents from Late Antiquity.2 And one should mention its surprising prominence in Islam-the story was told and retold some seven times in the Koran and was subsequently subject to further elaboration among Muslim exegetes and storytellers.3 My purpose in this essay is to carry forward work I have already done on this text to the figures of St. -

Rncm Chamber Music Festival Songs Without Words Rncm Chamber Music Festival Songs Without Words

Friday 04 – Sunday 06 March 2016 RNCM CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL SONGS WITHOUT WORDS RNCM CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL SONGS WITHOUT WORDS WELCOME The RNCM Chamber Music Festival plays an enormous role in the story of the College and is a major event in our calendar. Chamber music is at the core at what we do - the RNCM has a proud tradition of chamber ensemble training and our alumni appear with high profile ensembles such as the Elias, Heath and Navarra String Quartets plus the Gould Piano Trio to name but a few. Every year, the Chamber Music Festival goes from strength to strength, presenting the opportunity to see our wonderful students, internationally renowned staff and special guests perform beautiful music across a jam-packed weekend. This year is no exception, as we explore German Romanticism in Songs Without Words. We focus particularly on the music of Mendelssohn and Schumann and our students will be involved in a major composition project, as they are asked to create responses to Mendelssohn’s Songs Without Words. So the Festival will include works from across the 19th century but will also dip into the 20th century with composers such as Richard Strauss. This year’s line-up features some of the finest musicians performing today including the Talich Quartet, Elias Quartet, Michelangelo Quartet, plus RNCM Junior Fellows the Solem Quartet and our International Artist chamber ensemble the Diverso String Quartet. We also welcome chamber groups from Chetham’s, St Mary’s, Junior RNCM, the Royal Irish Academy of Music and Sheffield Music Academy. So please join us and immerse yourself in this weekend of lush musical landscapes. -

Young Americans to Emotional Rescue: Selected Meetings

YOUNG AMERICANS TO EMOTIONAL RESCUE: SELECTING MEETINGS BETWEEN DISCO AND ROCK, 1975-1980 Daniel Kavka A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2010 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Katherine Meizel © 2010 Daniel Kavka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Disco-rock, composed of disco-influenced recordings by rock artists, was a sub-genre of both disco and rock in the 1970s. Seminal recordings included: David Bowie’s Young Americans; The Rolling Stones’ “Hot Stuff,” “Miss You,” “Dance Pt.1,” and “Emotional Rescue”; KISS’s “Strutter ’78,” and “I Was Made For Lovin’ You”; Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy“; and Elton John’s Thom Bell Sessions and Victim of Love. Though disco-rock was a great commercial success during the disco era, it has received limited acknowledgement in post-disco scholarship. This thesis addresses the lack of existing scholarship pertaining to disco-rock. It examines both disco and disco-rock as products of cultural shifts during the 1970s. Disco was linked to the emergence of underground dance clubs in New York City, while disco-rock resulted from the increased mainstream visibility of disco culture during the mid seventies, as well as rock musicians’ exposure to disco music. My thesis argues for the study of a genre (disco-rock) that has been dismissed as inauthentic and commercial, a trend common to popular music discourse, and one that is linked to previous debates regarding the social value of pop music. -

THE NATURE and POWER of SATAN Theorizing About the Nature

CHAPTER THREE THE NATURE AND POWER OF SATAN Theorizing about the nature, origin, and cosmological status of Satan occurs among the selected writings, especially among the later ones. However, there is an obvious lack of "speculative" interest in the sense of seeking to work out a complete cosmology of evil. Concepts as to the origin, abode, and ultimate future of Satan are often very diverse, and there are only a small number of referen ces. An analysis and interpretation of the nature of Satan as conceiv ed by the early Christian tradition will be therefore necessarily less comprehensive than a discussion of his activities. There are some basic understandings as to the nature and power of Satan common to most of the selected writers, however, and they are best summarized by the New Testament phrases: Satan, the "prince of the power of the air," "ruler of demons," "ruler of the world," and "god of this age." A. SATAN: PRINCE OF THE POWER OF THE AIR 1. Origin of Satan For the most part, the New Testament writers make no theoreti cal assertions as to the origin of Satan. However, a number of passages by choice of words and phraseology seem to reflect the idea of Satan as a fallen angel who is chief among a class of fallen angels, an idea which appears frequently in apocalyptic literature.1 II Peter 2 :4, for example, refers to the angels that sinned and were cast into hell. Jude 6 mentions "the angels that did not keep their own position but left their proper dwelling .. -

What Handel Taught the Viennese About the Trombone

291 What Handel Taught the Viennese about the Trombone David M. Guion Vienna became the musical capital of the world in the late eighteenth century, largely because its composers so successfully adapted and blended the best of the various national styles: German, Italian, French, and, yes, English. Handel’s oratorios were well known to the Viennese and very influential.1 His influence extended even to the way most of the greatest of them wrote trombone parts. It is well known that Viennese composers used the trombone extensively at a time when it was little used elsewhere in the world. While Fux, Caldara, and their contemporaries were using the trombone not only routinely to double the chorus in their liturgical music and sacred dramas, but also frequently as a solo instrument, composers elsewhere used it sparingly if at all. The trombone was virtually unknown in France. It had disappeared from German courts and was no longer automatically used by composers working in German towns. J.S. Bach used the trombone in only fifteen of his more than 200 extant cantatas. Trombonists were on the payroll of San Petronio in Bologna as late as 1729, apparently longer than in most major Italian churches, and in the town band (Concerto Palatino) until 1779. But they were available in England only between about 1738 and 1741. Handel called for them in Saul and Israel in Egypt. It is my contention that the influence of these two oratorios on Gluck and Haydn changed the way Viennese composers wrote trombone parts. Fux, Caldara, and the generations that followed used trombones only in church music and oratorios. -

The History of the Louisiana State University School of Music

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1968 The iH story of the Louisiana State University School of Music. Charlie Walton Roberts Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Roberts, Charlie Walton Jr, "The iH story of the Louisiana State University School of Music." (1968). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1458. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1458 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 68-16,326 ROBERTS, Jr., Charlie Walton, 1935- THE HISTORY OF THE LOUISIANA STATE UNIVER SITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC. Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ed.D., 1968 Music University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE HISTORY OF THE LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education i n The Department of Education by Charlie Walton Roberts, Jr. B.Mu.Ed., Louisiana State University, 1957 M.A., Louisiana Polytechnic Institute, 1964 May, 1968 ACKNOWLEDGMENT The author acknowledges with gratitude the assistance of Dr. William M. Smith, his major professor, for his guidance throughout this study and his graduate program at Louisiana State University. -

4474134-09A1a4-Booklet-CD98.626

2.K ach intensiver Auseinandersetzung mit dem er „kritische Bericht“, dieser Inbegriff Symbole werden zu Akteuren eines unserer Nsinfonischen Werk Mozarts und Beethovens Dgeduldigsten Forscherfleißes, begegnet Imagination entspringenden Theaters und habe ich meine Liebe zu Haydns Musik zugege- abseits seines Fachbezirks vielfachem Unver- treten, vielleicht auch nur für ein paar Minu- benermaßen erst relativ spät entdeckt. Seither ist ständnis. All diese Hieroglyphen und Linea- ten, wieder ins Rampenlicht einstiger Pracht es mir ein Anliegen, „Papa Haydn“ den Zopf abzu- mente, die vom Schreiber X zur Quelle Y, & Herrlichkeit. Wer war denn wohl der Ko- schneiden, den ihm das 19. und 20. Jahrhundert von zweifelhaften Wasserzeichen zu unech- pist, wer waren die fleißigen Leute, die dem haben wachsen lassen. Die Gesamteinspielung der ten Tintensorten führen – diese kryptischen Hofkapellmeister des Fürsten Nikolaus von Haydn-Sinfonien ist für meine Musiker und mich Überlieferungsnachweise und Stammbäume, Eszterházy bei seiner unablässigen Produkti- eine höchst interessante Aufgabe und eine große fachlich korrekter als „Stemmata“ bezeich- on zur Hand gingen? Für wen notierte Herausforderung, bietet sich doch mit diesem ehr- net: Müssen wir uns wirklich jede noch so „Schreiber F“, wenn ihm noch ein paar geizigen Projekt die einmalige Chance, die Ent- hypothetische Frage stellen lassen, ehe uns Nachtstunden blieben, einen zweiten Stim- wicklung der klassischen Sinfonie hautnah nachzu- die Kontaktaufnahme mit dem eigentlichen mensatz? Wie viele Kreutzer mag er dafür erleben. In Zeiten musikalischen (und gesellschaft- Notentext gestattet wird? bekommen, wen davon möglicherweise er- DEUTSCH lichen) Wandels war Haydn Stürmer, Dränger, Das hängt von der eigenen Art der Be- nährt haben? War’s seine Fehlsichtigkeit, Sucher und Finder zugleich. -

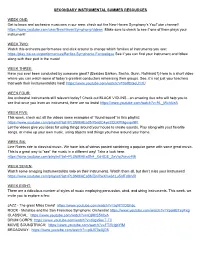

Secondary Instrumental Summer Resources Week

SECONDARY INSTRUMENTAL SUMMER RESOURCES WEEK ONE: Get to know real orchestra musicians in our area: check out the New Haven Symphony’s YouTube channel! https://www.youtube.com/user/NewHavenSymphony/videos Make sure to check to see if one of them plays your instrument! WEEK TWO: Watch this orchestra performance and click around to change which families of instruments you see: https://play.lso.co.uk/performances/Berlioz-Symphonie-Fantastique See if you can find your instrument and follow along with their part in the music! WEEK THREE: Have you ever been conducted by someone great? (Besides Barkon, Socha, Gunn, Rothbard?) Here is a short video where you can watch some of today’s greatest conductors rehearsing their groups. See, it’s not just your teachers that work their instrumentalists hard! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0otfQGoU13U WEEK FOUR: Are orchestral instruments still relevant today? Check out BLACK VIOLINS - an amazing duo who will help you to see that once you learn an instrument, there are no limits! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9I-_jWchUeA WEEK FIVE: This week, check out all the videos some examples of “found sound” in this playlist: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL3Nl9lAEaSN7baBC4yeSQLKPMgvxpr9Pi. Let the videos give you ideas for using things around your house to create sounds. Play along with your favorite songs, or make up your own music, using objects and things you have around your home. WEEK SIX: Line Riders ride to classical music. We have lots of videos posted combining a popular game with some great music. This is a great way to “see” the music in a different way! Take a look here: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL3Nl9lAEaSN4_Xd-0DE_ZeViotAwcu4Mi WEEK SEVEN: Watch some amazing instrumentalists solo on their instruments. -

Vivaldi's Four Seasons

Vivaldi's Four Seasons Paul Dyer AO Artistic Director 2019 Australian Brandenburg Orchestra SYDNEY PROGRAM City Recital Hall Telemann Concerto for 4 Violins in G major, TWV 40:201 Friday 1 November 7:00PM Directed by Matthew Bruce, Baroque violin Saturday 2 November 2:00PM Telemann Ouverture-Suite in C major, Water Music, TWV 55:C3 (Matinee) Directed by Ben Dollman, Baroque violin Saturday 2 November 7:00PM i Ouverture Wednesday 6 November 7:00PM ii Sarabande. Die schlafende Thetis (The sleeping Thetis) Wednesday 13 November 7:00PM iii Bourée. Die erwachende Thetis (Thetis awakening) Friday 15 November 7:00PM iv Loure. Der verliebte Neptunus (Neptune in love) Parramatta (Riverside Theatres) v Gavotte. Die spielenden Najaden (Playing Naiads) Monday 4 November 7:00pm vi Harlequinade. Der scherzenden Tritonen (The joking Triton) vii Der stürmende Aeolus (The stormy Aeolus) MELBOURNE viii Menuet. Der angenehme Zephir (The pleasant Zephir) Melbourne Recital Centre ix Gigue. Ebbe und Fluth (Ebb and Flow) Saturday 9 November 7:00PM x Canarie. Die lustigen Bots Leute (The merry Boat People) Sunday 10 November 5:00PM Interval Vivaldi Le Quattro Stagioni (The Four Seasons), Op. 8 No. 1-4 Solo Baroque violin, Shaun Lee-Chen Concerto No. 1 La primavera (Spring), RV 269 i Allegro ii Largo iii Allegro Concerto No. 2 L’estate (Summer), RV 315 i Allegro non molto–Allegro ii Adagio–Presto–Adagio iii Presto Concerto No. 3 L’autunno (Autumn), RV 293 i Allegro ii Adagio molto iii Allegro Concerto No. 4 L’inverno (Winter), RV 297 i Allegro non molto ii Largo iii Allegro CHAIRMAN’S 11 Proudly supporting our guest artists.