ESTER NINSHABA-SOSS.Pdf (2.327Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Towards Sustainable Peace in Uganda?

TOWARDS SUSTAINABLE PEACE IN UGANDA? - a study of peacebuilding in northern Uganda and the involvement of the civil society during the LRA/ government of Uganda peace process of 2006-2007 Anna Svenson Spring term of 2007 Master thesis Political Sciences, POM 556 Supervisor: Emil Uddhammar TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................................. 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..................................................................................................... 7 PART I – INTRODUCTION OF THE PROJECT AND METHODOLOGICAL DISCUSSION ........................................................................................................................... 8 1. INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................ 9 1.1 Background ...................................................................................................................... 9 1.2 Purpose and research questions...................................................................................... 10 1.3 Limitations ..................................................................................................................... 11 1.4 Disposition ..................................................................................................................... 11 2. METHODOLOGICAL DISCUSSION ............................................................................ 13 2.1 The project – choice and -

The Gulf Crisis: the Impasse Between Mogadishu and the Regions 4

ei September-October 2017 Volume 29 Issue 5 The Gulf Engulfing the Horn of Africa? Contents 1. Editor's Note 2. Entre le GCC et l'IGAD, les relations bilatérales priment sur l'aspect régional 3. The Gulf Crisis: The Impasse between Mogadishu and the regions 4. Turkish and UAE Engagement in Horn of Africa and Changing Geo-Politics of the Region 1 Editorial information This publication is produced by the Life & Peace Institute (LPI) with support from the Bread for the World, Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) and Church of Sweden International Department. The donors are not involved in the production and are not responsible for the contents of the publication. Editorial principles The Horn of Africa Bulletin is a regional policy periodical, monitoring and analysing key peace and security issues in the Horn with a view to inform and provide alternative analysis on on-going debates and generate policy dialogue around matters of conflict transformation and peacebuilding. The material published in HAB represents a variety of sources and does not necessarily express the views of the LPI. Comment policy All comments posted are moderated before publication. Feedback and subscriptions For subscription matters, feedback and suggestions contact LPI’s Horn of Africa Regional Programme at [email protected]. For more LPI publications and resources, please visit: www.life-peace.org/resources/ Life & Peace Institute Kungsängsgatan 17 753 22 Uppsala, Sweden ISSN 2002-1666 About Life & Peace Institute Since its formation, LPI has carried out programmes for conflict transformation in a variety of countries, conducted research, and produced numerous publications on nonviolent conflict transformation and the role of religion in conflict and peacebuilding. -

Special Report No

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 490 | FEBRUARY 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE w w w .usip.org North Korea in Africa: Historical Solidarity, China’s Role, and Sanctions Evasion By Benjamin R. Young Contents Introduction ...................................3 Historical Solidarity ......................4 The Role of China in North Korea’s Africa Policy .........7 Mutually Beneficial Relations and Shared Anti-Imperialism..... 10 Policy Recommendations .......... 13 The Unknown Soldier statue, constructed by North Korea, at the Heroes’ Acre memorial near Windhoek, Namibia. (Photo by Oliver Gerhard/Shutterstock) Summary • North Korea’s Africa policy is based African arms trade, construction of owing to African governments’ lax on historical linkages and mutually munitions factories, and illicit traf- sanctions enforcement and the beneficial relationships with African ficking of rhino horns and ivory. Kim family regime’s need for hard countries. Historical solidarity re- • China has been complicit in North currency. volving around anticolonialism and Korea’s illicit activities in Africa, es- • To curtail North Korea’s illicit activ- national self-reliance is an under- pecially in the construction and de- ity in Africa, Western governments emphasized facet of North Korea– velopment of Uganda’s largest arms should take into account the histor- Africa partnerships. manufacturer and in allowing the il- ical solidarity between North Korea • As a result, many African countries legal trade of ivory and rhino horns and Africa, work closely with the Af- continue to have close ties with to pass through Chinese networks. rican Union, seek cooperation with Pyongyang despite United Nations • For its part, North Korea looks to China, and undercut North Korean sanctions on North Korea. -

Haji Yusuf Iman Guled

Haji Yusuf Iman Guled Justice and Welfare Party of Somaliland ( UCID ) ⢠Haji Yusuf Iman Guled , former Defense Minister of Somalia and a Business Magnate Premierzy Somalii. 14 lutego 2009 ) ⢠premier - elekt Mohamed Mohamud Guled ( 16 grudnia - 24 grudnia 2008 ) ⢠Omar Abdirashid Circonscription d'Est Gashamo. Zone Degehabur . Son représentant actuel est Abdulkerim Ahmed Guled . Voir aussi ⢠Circonscriptions législatives ( Éthiopie )⢠Conseil Hasan Guled Aptidon. Guled Aptidon Z Wikipedia Hasan Guled Aptidon , Hassan Hasan Guled Aptidon Z Wikipedia Hasan Guled Aptidon , Has Saida Ismail is the daughter of Haji Bashir Ismail Yusuf, the first President of the Somali National Assembly during Somalia's early civilian administration. Her brother, Abdullahi Haji Bashir Ismail, is a Deputy Director-General of Somali Immigration & Naturalization, One of the high rank Senior Somali Administration Officers, as well as a writer of Politics and History. Ismail later also entered politics, serving as Vice-Minister of Finance in the Transitional National Government (TNG) between 2000 and 2004. Haji Yusuf Iman Guled (Somali: Xaaji Yuusuf Imaan Guleed, Arabic: Øاجي يوس٠إيمان جوليد) was a Somali politician. Biography. Guled was raised in Somalia. He served as the newly independent country's Minister of Defence during the 1960s, and was a key figure in the nation's early civilian administration.[1] [2]. See also. Haji Bashir Ismail Yusuf. Osman Haji. References. Europa Publications Limited, The Middle East: a survey and directory of the countries of the Middle East, (Europa Publications., 1967). Haji Yusuf Iman Guled was a Somali politician. -

Following the Oil Road a Case Study Assessing the Vulnerability of Women Under the Impact of Development-Induced Migration in Western Uganda

Following the Oil Road A case study assessing the vulnerability of women under the impact of development-induced migration in Western Uganda M.Sc Thesis International Development Studies Catharina Nickel Wageningen University Student number 851018-599-080 July 2016 Following the Oil Road A case study assessing the vulnerability of women under the impact of development-induced migration in Western Uganda Catharina Nickel July 2016 M.Sc. Thesis International Development Studies Communication, Philosophy and Technology Group WAGENINGEN UNIVERSITY Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Han van Dijk Examiner: Dr. Gemma van der Haar Copyright 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without the prior consent of the author. Abstract The objective of this M.Sc. thesis is to assess the vulnerability of women under the impact of the development-induced migration that is currently taking place in the Lake Albert basin in Western Uganda. It provides a “snapshot” of the current situation in Hoima and Buliisa and intends to support the wider documentation of the social implications connected to the envisioned oil drilling activities in Western Uganda. This information will better enable scientists and practitioners to reconstruct the advent of certain social structures, even at a later stage in the process. The research presented builds on well-known studies regarding the relationship between natural resources and conflict. Moreover, it uses common approaches in the field of disaster risk reduction theory to determine the vulnerability of households and individuals. Designed as an exploratory case study, theories are used as a starting point and followed by closer examination of real-life cases, enabling the development of a deeper understanding. -

Download=True

“WE LIVE IN PERPETUAL FEAR” VIOLATIONS AND ABUSES OF FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION IN SOMALIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Somali journalists denied access to photograph an Al-Shabaab attack site in (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. Mogadishu in January 2020. © Private https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AFR 52/1442/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 2. METHODOLOGY 9 3. BACKGROUND 11 3.1 CONFLICT AND CIVILIAN SUFFERING 11 3.2 MEDIA AND SOCIAL MEDIA USE 12 3.3 TREATMENT OF MEDIA AND JOURNALISTS 12 3.4 HEIGHTENED POLITICAL TENSION IN 2018 AND 2019 13 4. INTERNATIONAL AND REGIONAL LEGAL FRAMEWORK 15 4.1 NATIONAL LEGAL FRAMEWORK 17 5. -

AFRICA Al-Shabaab Down but Not Out

AFRICA Al-Shabaab Down But Not Out OE Watch Commentary: The fight against al-Shabaab in Somalia has been going on for several years, and there have been reports that the terrorist group has been losing strength and territory. Nevertheless, it is still able to mount significant operations against the Somali National Army, the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), and members of the Somali government. As the accompanying excerpted article from The East African reports, not only does the group extort money from businesses in rural areas, but it also operates in the capital city, Mogadishu (from where it was forced out in 2011). Since President Farmaajo assumed office two years ago, AMISOM has reportedly not liberated any new territory. One reason for this might be that the nations contributing troops to that mission frequently pursue different strategies and interests, thus presenting less than a unified Although al Shabaab has been weakened by AMISOM forces and the Somali National Army, it is still able to launch devastating attacks in the country. front. Still another reason might be, with 2020 elections Source: Skilla1st via Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Djiboutian_forces_artillery_ready_to_fire_on_Al-Shabaab_militants_near_the_town_of_ Buula_Burde,_Somalia.jpg, CC BY-SA 4.0 approaching, Farmaajo’s government is distracted. Additionally, Farmaajo has poor relations with the leaders of three regional states, possibly compounding the central government’s diificulties in combating the terrorists. While Somali domestic politics play out, and AMISOM shows its fractures, al-Shabaab has taken advantage of the situation to infiltrate government agencies. The killing of Mogadishu’s mayor by one of his staff members who turned out to be a suicide bomber bears testament to that. -

A Foreign Policy Determined by Sitting Presidents: a Case

T.C. ANKARA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A FOREIGN POLICY DETERMINED BY SITTING PRESIDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF UGANDA FROM INDEPENDENCE TO DATE PhD Thesis MIRIAM KYOMUHANGI ANKARA, 2019 T.C. ANKARA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A FOREIGN POLICY DETERMINED BY SITTING PRESIDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF UGANDA FROM INDEPENDENCE TO DATE PhD Thesis MIRIAM KYOMUHANGI SUPERVISOR Prof. Dr. Çınar ÖZEN ANKARA, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................ i ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................... iv FIGURES ................................................................................................................... vi PHOTOS ................................................................................................................... vii INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER ONE UGANDA’S JOURNEY TO AUTONOMY AND CONSTITUTIONAL SYSTEM I. A COLONIAL BACKGROUND OF UGANDA ............................................... 23 A. Colonial-Background of Uganda ...................................................................... 23 B. British Colonial Interests .................................................................................. 32 a. British Economic Interests ......................................................................... -

Militarization in East Africa 2017

Adams Annotated Bibliography on Militarization in East African 1 SSHRC Partnership: Conjugal Slavery in Wartime Masculinities and Femininities Thematic Group Annotated Bibliography on Militarization of East Africa Aislinn Adams, Research Assistant Adams Annotated Bibliography on Militarization in East African 2 Table of Contents Statistics and Military Expenditure ...................................................................................... 7 World Bank. “Military Expenditure (% of GDP).” 1988-2015. ..................................................... 7 Military Budget. “Military Budget in Uganda.” 2001-2012. ........................................................... 7 World Bank. “Expenditure on education as % of total government expenditure (%).” 1999-2012. ........................................................................................................................................................ 7 World Bank. “Health expenditure, public (% of GDP).” 1995-2014. ............................................. 7 World Health Organization. “Uganda.” ......................................................................................... 7 - Total expenditure on health as % if GDP (2014): 7.2% ......................................................... 7 United Nations Development Programme. “Expenditure on health, total (% of GDP).” 2000- 2011. ................................................................................................................................................ 7 UN Data. “Country Profile: Uganda.” -

External Interventions in Somalia's Civil War. Security Promotion And

External intervention in Somalia’s civil war Mikael Eriksson (Editor) Eriksson Mikael war civil Somalia’s intervention in External The present study examines external intervention in Somalia’s civil war. The focus is on Ethiopia’s, Kenya’s and Uganda’s military engagement in Somalia. The study also analyses the political and military interests of the intervening parties and how their respective interventions might affect each country’s security posture and outlook. The aim of the study is to contribute to a more refined under- standing of Somalia’s conflict and its implications for the security landscape in the Horn of Africa. The study contains both theoretical chapters and three empirically grounded cases studies. The main finding of the report is that Somalia’s neighbours are gradually entering into a more tense political relationship with the government of Somalia. This development is character- ized by a tension between Somalia’s quest for sovereignty and neighbouring states’ visions of a decentralized Somali state- system capable of maintaining security across the country. External Intervention in Somalia’s civil war Security promotion and national interests? Mikael Eriksson (Editor) FOI-R--3718--SE ISSN1650-1942 www.foi.se November 2013 FOI-R--3718--SE Mikael Eriksson (Editor) External Intervention in Somalia’s civil war Security promotion and national interests? Cover: Scanpix (Photo: TT, CORBIS) 1 FOI-R--3718--SE Titel Extern intervention i Somalias inbördeskrig: Främjande av säkerhet och nationella intressen? Title External intervention in Somalia’s civil war: security promotion and national Interests? Rapportnr/Report no FOI-R--3718--SE Månad/Month November Utgivningsår/Year 2013 Antal sidor/Pages 137 ISSN 1650-1942 Kund/Customer Försvarsdepartementet/Ministry of Defence Projektnr/Project no A11306 Godkänd av/Approved by Maria Lignell Jakobsson Ansvarig avdelning Försvarsanalys/Defence Analysis Detta verk är skyddat enligt lagen (1960:729) om upphovsrätt till litterära och konstnärliga verk. -

Improving the Protective Environment and Access to Child

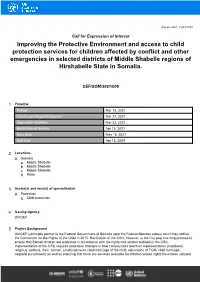

Sep 25, 2021, 1:22:53 PM Call for Expression of Interest Improving the Protective Environment and access to child protection services for children affected by conflict and other emergencies in selected districts of Middle Shabelle regions of Hirshabelle State in Somalia. CEF/SOM/2021/008 1 Timeline Posted Mar 13, 2021 Clarification Request Deadline Mar 17, 2021 Application Deadline Mar 23, 2021 Notification of Results Apr 15, 2021 Start Date May 15, 2021 End Date Apr 15, 2024 2 Locations A Somalia a Middle Shebelle b Middle Shebelle c Middle Shebelle d Hiran 3 Sector(s) and area(s) of specialization A Protection a Child protection 4 Issuing Agency UNICEF 5 Project Background UNICEF’s principle partner is the Federal Government of Somalia (and the Federal Member states) which has ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 2015. Ratification of the CRC, however, is the first step in a long process to ensure that Somali children are protected in accordance with the rights and articles outlined in the CRC. Implementation of the CRC requires normative changes in how communities and their representatives (traditional, religious, political, men, women, youth) perceive childhood (age of the child, elimination of FGM, child marriage, corporal punishment) as well as ensuring that there are services available for children whose rights have been violated or those who lack appropriate care and protection from adults. The Somali government is making strong headway in strengthening the protective environment for women and children and UNICEF is a committed partner providing both technical and financial resources to achieving these goals. -

2020 Somalia Humanitarian Needs Overview

HUMANITARIAN HUMANITARIAN PROGRAMME CYCLE 2020 NEEDS OVERVIEW ISSUED DECEMBER 2019 SOMALIA 1 HUMANITARIAN NEEDS OVERVIEW 2020 About Get the latest updates This document is consolidated by OCHA on behalf of the Humanitarian Country OCHA coordinates humanitarian action to ensure Team and partners. It provides a shared understanding of the crisis, including the crisis-affected people receive the assistance and protection they need. It works to overcome obstacles most pressing humanitarian need and the estimated number of people who need that impede humanitarian assistance from reaching assistance. It represents a consolidated evidence base and helps inform joint people affected by crises, and provides leadership in strategic response planning. mobilizing assistance and resources on behalf of the The designations employed and the presentation of material in the report do not humanitarian system. imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the www.unocha.org/somalia United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of twitter.com/OCHA_SOM its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. PHOTO ON COVER Photo: WHO/Fozia Bahati Humanitarian Response aims to be the central website for Information Management tools and services, enabling information exchange between clusters and IASC members operating within a protracted or sudden onset crisis. www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/ operations/somalia Humanitarian InSight supports decision-makers by giving them access to key humanitarian data. It provides the latest verified information on needs and delivery of the humanitarian response as well as financial contributions. www.hum-insight.info/plan/667 The Financial Tracking Service (FTS) is the primary provider of continuously updated data on global humanitarian funding, and is a major contributor to strategic decision making by highlighting gaps and priorities, thus contributing to effective, efficient and principled humanitarian assistance.