Download=True

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gulf Crisis: the Impasse Between Mogadishu and the Regions 4

ei September-October 2017 Volume 29 Issue 5 The Gulf Engulfing the Horn of Africa? Contents 1. Editor's Note 2. Entre le GCC et l'IGAD, les relations bilatérales priment sur l'aspect régional 3. The Gulf Crisis: The Impasse between Mogadishu and the regions 4. Turkish and UAE Engagement in Horn of Africa and Changing Geo-Politics of the Region 1 Editorial information This publication is produced by the Life & Peace Institute (LPI) with support from the Bread for the World, Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) and Church of Sweden International Department. The donors are not involved in the production and are not responsible for the contents of the publication. Editorial principles The Horn of Africa Bulletin is a regional policy periodical, monitoring and analysing key peace and security issues in the Horn with a view to inform and provide alternative analysis on on-going debates and generate policy dialogue around matters of conflict transformation and peacebuilding. The material published in HAB represents a variety of sources and does not necessarily express the views of the LPI. Comment policy All comments posted are moderated before publication. Feedback and subscriptions For subscription matters, feedback and suggestions contact LPI’s Horn of Africa Regional Programme at [email protected]. For more LPI publications and resources, please visit: www.life-peace.org/resources/ Life & Peace Institute Kungsängsgatan 17 753 22 Uppsala, Sweden ISSN 2002-1666 About Life & Peace Institute Since its formation, LPI has carried out programmes for conflict transformation in a variety of countries, conducted research, and produced numerous publications on nonviolent conflict transformation and the role of religion in conflict and peacebuilding. -

Somalia Terror Threat

THECHRISTOPHER TERROR February 12, THREAT FROM THE TERROR THREAT FROM SOMALIA THE INTERNATIONALIZATION OF AL SHABAAB CHRISTOPHER HARNISCH APPENDICES AND MAPS BY KATHERINE ZIMMERMAN FEBRUARY 12, 2010 A REPORT BY THE CRITICAL THREATS PROJECT OF THE AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE THE TERROR THREAT FROM SOMALIA CHRISTOPHER HARNISCH February 12, 2010 Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 IMPORTANT GROUPS AND ORGANIZATIONS IN SOMALIA 3 NOTABLE INDIVIDUALS 4 INTRODUCTION 8 ORIGINS OF AL SHABAAB 10 GAINING CONTROL, GOVERNING, AND MAINTAINING CONTROL 14 AL SHABAAB’S RELATIONSHIP WITH AL QAEDA, THE GLOBAL JIHAD MOVEMENT, AND ITS GLOBAL IDEOLOGY 19 INTERNATIONAL RECRUITING AND ITS IMPACT 29 AL SHABAAB’S INTERNATIONAL THREATS 33 THREAT ASSESSMENT AND CONCLUSION 35 APPENDIX A: TIMELINE OF MAJOR SECURITY EVENTS IN SOMALIA 37 APPENDIX B: MAJOR SUICIDE ATTACKS AND ASSASSINATIONS CLAIMED BY OR ATTRIBUTED TO AL SHABAAB 47 NOTES 51 Maps MAP OF THE HORN OF AFRICA AND MIDDLE EAST 5 POLITICAL MAP OF SOMALIA 6 MAP OF ISLAMIST-CONTROLLED AND INFLUENCED AREAS IN SOMALIA 7 www.criticalthreats.org THE TERROR THREAT FROM SOMALIA CHRISTOPHER HARNISCH February 12, 2010 Executive Summary hree hundred people nearly died in the skies of and assassinations. Al Shabaab’s primary objectives at TMichigan on Christmas Day, 2009 when a Niger- the time of the Ethiopian invasion appeared to be ian terrorist attempted to blow up a plane destined geographically limited to Somalia, and perhaps the for Detroit. The terrorist was an operative of an al Horn of Africa. The group’s rhetoric and behavior, Qaeda franchise based in Yemen called al Qaeda in however, have shifted over the past two years reflect- the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). -

AFRICA Al-Shabaab Down but Not Out

AFRICA Al-Shabaab Down But Not Out OE Watch Commentary: The fight against al-Shabaab in Somalia has been going on for several years, and there have been reports that the terrorist group has been losing strength and territory. Nevertheless, it is still able to mount significant operations against the Somali National Army, the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), and members of the Somali government. As the accompanying excerpted article from The East African reports, not only does the group extort money from businesses in rural areas, but it also operates in the capital city, Mogadishu (from where it was forced out in 2011). Since President Farmaajo assumed office two years ago, AMISOM has reportedly not liberated any new territory. One reason for this might be that the nations contributing troops to that mission frequently pursue different strategies and interests, thus presenting less than a unified Although al Shabaab has been weakened by AMISOM forces and the Somali National Army, it is still able to launch devastating attacks in the country. front. Still another reason might be, with 2020 elections Source: Skilla1st via Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Djiboutian_forces_artillery_ready_to_fire_on_Al-Shabaab_militants_near_the_town_of_ Buula_Burde,_Somalia.jpg, CC BY-SA 4.0 approaching, Farmaajo’s government is distracted. Additionally, Farmaajo has poor relations with the leaders of three regional states, possibly compounding the central government’s diificulties in combating the terrorists. While Somali domestic politics play out, and AMISOM shows its fractures, al-Shabaab has taken advantage of the situation to infiltrate government agencies. The killing of Mogadishu’s mayor by one of his staff members who turned out to be a suicide bomber bears testament to that. -

Improving the Protective Environment and Access to Child

Sep 25, 2021, 1:22:53 PM Call for Expression of Interest Improving the Protective Environment and access to child protection services for children affected by conflict and other emergencies in selected districts of Middle Shabelle regions of Hirshabelle State in Somalia. CEF/SOM/2021/008 1 Timeline Posted Mar 13, 2021 Clarification Request Deadline Mar 17, 2021 Application Deadline Mar 23, 2021 Notification of Results Apr 15, 2021 Start Date May 15, 2021 End Date Apr 15, 2024 2 Locations A Somalia a Middle Shebelle b Middle Shebelle c Middle Shebelle d Hiran 3 Sector(s) and area(s) of specialization A Protection a Child protection 4 Issuing Agency UNICEF 5 Project Background UNICEF’s principle partner is the Federal Government of Somalia (and the Federal Member states) which has ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 2015. Ratification of the CRC, however, is the first step in a long process to ensure that Somali children are protected in accordance with the rights and articles outlined in the CRC. Implementation of the CRC requires normative changes in how communities and their representatives (traditional, religious, political, men, women, youth) perceive childhood (age of the child, elimination of FGM, child marriage, corporal punishment) as well as ensuring that there are services available for children whose rights have been violated or those who lack appropriate care and protection from adults. The Somali government is making strong headway in strengthening the protective environment for women and children and UNICEF is a committed partner providing both technical and financial resources to achieving these goals. -

2020 Somalia Humanitarian Needs Overview

HUMANITARIAN HUMANITARIAN PROGRAMME CYCLE 2020 NEEDS OVERVIEW ISSUED DECEMBER 2019 SOMALIA 1 HUMANITARIAN NEEDS OVERVIEW 2020 About Get the latest updates This document is consolidated by OCHA on behalf of the Humanitarian Country OCHA coordinates humanitarian action to ensure Team and partners. It provides a shared understanding of the crisis, including the crisis-affected people receive the assistance and protection they need. It works to overcome obstacles most pressing humanitarian need and the estimated number of people who need that impede humanitarian assistance from reaching assistance. It represents a consolidated evidence base and helps inform joint people affected by crises, and provides leadership in strategic response planning. mobilizing assistance and resources on behalf of the The designations employed and the presentation of material in the report do not humanitarian system. imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the www.unocha.org/somalia United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of twitter.com/OCHA_SOM its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. PHOTO ON COVER Photo: WHO/Fozia Bahati Humanitarian Response aims to be the central website for Information Management tools and services, enabling information exchange between clusters and IASC members operating within a protracted or sudden onset crisis. www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/ operations/somalia Humanitarian InSight supports decision-makers by giving them access to key humanitarian data. It provides the latest verified information on needs and delivery of the humanitarian response as well as financial contributions. www.hum-insight.info/plan/667 The Financial Tracking Service (FTS) is the primary provider of continuously updated data on global humanitarian funding, and is a major contributor to strategic decision making by highlighting gaps and priorities, thus contributing to effective, efficient and principled humanitarian assistance. -

Lifesaving Response and Preparedness to Flood-Prone Areas in Hiran and Middle Shabelle

Final Version 2: 18 October 2018 SHF Funded: Lifesaving Response and Preparedness to Flood-Prone Areas in Hiran and Middle Shabelle Introduction This document lays out the approach to allocating funds from the Somalia Humanitarian Fund (SHF) reserve allocation to respond to the highest and immediate needs (shelter and NFIs) of communities that are affected by heavy rains in flood prone regions of Hiran and Middle Shabelle. A total of US$1.3 million will be made available to distribute and preposition emergency shelter kits/NFIs to most vulnerable communities. Situation analysis The Deyr rainy season (September- December) begun in some parts of Somalia and is expected to continue spreading over the coming weeks. A recent forecast issued by the Greater Horn of Africa Climate Outlook Forum indicates a 40 per cent change of above-average rainfall in most parts of Somalia except north-western areas of Somalia. Though the rains are expected to further improve food production, average to above average rainfall will likely lead to increased risk of flooding along the Juba and Shabelle River. Riverine communities in flood prone Hiran and Middle Shabelle regions often bear the brunt of floods. The heavy rains in June 2018 affected nearly 306,000 people in Hirshabelle State and displaced approximately 186,000 people with population in Beletweyne being the worst affected. Current projections from the Shelter cluster shows that about 150,000 people in Hirshabelle will be affected by the heavy rains and imminent floods. While the needs of flood affected communities are numerous, provision of basic non-food items and emergency shelter always remains a priority in terms of immediate life-saving response. -

Scramble for the Horn of Africa – Al-Shabaab Vs. Islamic State

DOI: 10.32576/nb.2019.4.3 Nation and Security 2019. Issue 4. | 14–29. Viktor Marsai Scramble for the Horn of Africa – Al-Shabaab vs. Islamic State Over the past three years, the so-called Islamic State (IS) has made significant pro- gress in building an international network of Jihadist groups that pledged allegiance to the organisation. The affiliates of IS are both new-born movements like the Islamic State in Libya, and older groups like Boko Haram in Nigeria. The latter are much more valuable for the ‘Caliphate’ because they have broad experience and capacities that allow them to operate independently of IS. In its global Jihad, therefore, the Islamic State tried to gain the support of the members of former al-Qaeda franchises, shifting their alliances from Ayman al-Zawahiri to Abu Bakr al-Bagdadi. The paper offers an overview of such IS efforts in the Horn of Africa and an evaluation of how successful this quest had been until 2017. Keywords: Somalia, Libya, terrorism, extremism, Africa, Islamic State, al-Shabaab Al-Shabaab in Somalia (full name: Harakat al-Shabaab al-Mujahideen, or ‘Movement of Striving Youth’) is distinct from other Jihadist organisations. Al-Shabaab established and extended territorial control in Somalia over at least 250,000 square kilometres in 2008–2009 – five years prior to IS.1 It created effective administrative and judiciary systems and launched military, political and ideological attacks against the Transitional Federal Government of Somalia and its foreign supporters. In 2011–2012, offensives of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) and the Somali National Army (SNA) inflicted serious setbacks on the movement, and it had to vacate the capital, Mogadishu. -

Reporthrvelectoralprocessaug

Table of Contents LIST OF ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................................ 3 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Methodology ..................................................................................................................................... 7 II. Context .............................................................................................................................................. 8 Overall Human Rights Situation ............................................................................................................... 8 The 2016 Electoral Process ....................................................................................................................... 9 III. Legal Framework ............................................................................................................................ 12 IV. Violations of Human Rights in the Context of the Electoral Processes .......................................... 13 The Rights to Life and Physical Integrity ................................................................................................... 14 The Rights to Liberty and Security and Freedom from torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.... 16 The Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression .................................................................................... -

Transition Initiatives for Stabilization Plus (Tis+) Program Year Three – Annual Work Plan

TRANSITION INITIATIVES FOR STABILIZATION PLUS (TIS+) PROGRAM YEAR THREE – ANNUAL WORK PLAN (OCTOBER 1, 2017 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2018) Revised November 2017 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by AECOM. Annual Work plan | Transition Initiatives for Stabilization Plus (TIS+) Program i TRANSITION INITIATIVES FOR STABILIZATION PLUS (TIS+) PROGRAM YEAR THREE – ANNUAL WORK PLAN (OCTOBER 1, 2017 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2018) Contract No: AID-623-C-15-00001 Submitted to: USAID | Somalia Prepared by: AECOM International Development DISCLAIMER: The authors’ views expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Year Three - Annual Work Plan | Transition Initiatives for Stabilization Plus (TIS+) Program i TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................................ ii Acronym List .............................................................................................................................................. iii Stabilization Context .................................................................................................................................. 5 Goals and Objectives of USAID and TIS+ ............................................................................................... 6 Methodology ........................................................................................................................................ -

Grass-Roots Dialogue in Hirshabelle State

Berghof Practice Report: Grass-Roots Dialogue in Hirshabelle State Grass-Roots Dialogue in Hirshabelle State Recommendations for Locally-Informed Federalism in Somalia Janel B. Galvanek Project Report May 2017 Executive Summary This project report with recommendations has been informed by a project that the Berghof Foundation carried out in 2015-2016 in Hirshabelle State in Somalia entitled “Building Federalism through Local Government Dialogue”. One component of this project entailed the implementation of six separate Somali dialogue assemblies – Shirarka – all taking place over six days with approximately 60 participants. This report is a brief summary of the pertinent issues that were discussed at these six assemblies in relation to the federalization process, the role of local government in a federal system, and the urgent need for conflict resolution and reconciliation in Hirshabelle State. The report begins with a brief explanation of the current status of and concerns about the ongoing federalization process in the country and then lays out five specific recommendations for national and international policy makers, based on the opinions and views of the citizens of Hirshabelle State that were collected during the Shirarka. These recommendations are 1) to support an inclusive and participatory system of federalism in the country, 2) to limit the top-down nature of the federalization process, 3) to encourage more Somali ownership, 4) to ensure the fair distribution of wealth, and 5) to address the need for reconciliation among the people of Somalia. Content 1 Introduction 3 2 Supporting an inclusive and participatory system of federalism 5 3 Limiting the top-down nature of the federalization process 6 4 Encouraging more Somali ownership 7 5 Ensuring the fair distribution of wealth 8 6 Addressing the need for reconciliation 10 7 Conclusion 11 8 Recommendations for international and national policy makers 12 © Berghof Foundation Operations GmbH 2017. -

1 Rev. 6 Project Name Support to Building

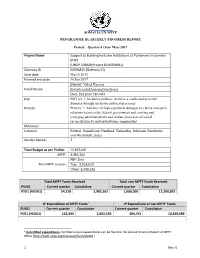

SOMALIA UN MPTF PROGRAMME QUARTERLY PROGRESS REPORT Period: Quarter-1 (Jan- Mar) 2017 Project Name Support to Building Inclusive Institutions of Parliament in Somalia (PSP) (UNDP SOM10 Project ID 00094911) Gateway ID 00096825 (Gateway ID) Start date March 2013 Planned end date 30 Jun 2017 (Name): Nahid Hussein Focal Person (Email): [email protected] (Tel): 252 (0)612863045 PSG PSG (s): 1: Inclusive politics: Achieve a stable and peaceful Somalia through inclusive political processes Priority Priority 1: Advance inclusive political dialogue to clarify and settle relations between the federal government and existing and emerging administrations and initiate processes of social reconciliation to restore between communities. Milestone Location Federal; Somaliland; Puntland, Galmudug, Jubaland, Southwest, and Hirshabelle states Gender Marker 2 Total Budget as per ProDoc 15,827,041 MPTF: 2,982,362 PBF: Zero Non MPTF sources: Trac: 3,918,619 Other: 8,290,236 Total MPTF Funds Received Total non-MPTF Funds Received PUNO Current quarter Cumulative Current quarter Cumulative PSG1 (4SOU1) 54,218 2,982,362 1,000,000 12,208,855 JP Expenditure of MPTF Funds1 JP Expenditure of non-MPTF Funds PUNO Current quarter Cumulative Current quarter Cumulative PSG1 (4SOU1) 132,344 2,603,130 284,755 10,818,888 1 Uncertified expenditures. Certified annual expenditures can be found in the Annual Financial Report of MPTF Office (http://mptf.undp.org/factsheet/fund/4SO00 ) 1 Rev. 6 SOMALIA UN MPTF PUNO Report approved by: Position/Title Signature 1. UNDP David Akopyan UNDP-Somalia Signed Copy on File (available Country Director (ai) upon request) QUARTER HIGHLIGHTS The impact of the UNDP Parliamentary Support Project (PSP) in terms of capacity development of Parliaments of Somalia has produced results as the new MPs 55 (M:53, W:2) of HirShabelle State Assembly were capacitated with necessary knowledge and information on parliamentary practices and businesses such as legislative process and oversight of the executive. -

S 2019 858 E.Pdf

United Nations S/2019/858* Security Council Distr.: General 1 November 2019 Original: English Letter dated 1 November 2019 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolution 751 (1992) concerning Somalia addressed to the President of the Security Council On behalf of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolution 751 (1992) concerning Somalia, and in accordance with paragraph 54 of Security Council resolution 2444 (2018), I have the honour to transmit herewith the final report of the Panel of Experts on Somalia. In this connection, the Committee would appreciate it if the present letter and the report were brought to the attention of the members of the Security Council and issued as a document of the Council. (Signed) Marc Pecsteen de Buytswerve Chair Security Council Committee pursuant to resolution 751 (1992) concerning Somalia * Reissued for technical reasons on 14 November 2019. 19-16960* (E) 141119 *1916960* S/2019/858 Letter dated 27 September 2019 from the Panel of Experts on Somalia addressed to the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolution 751 (1992) concerning Somalia In accordance with paragraph 54 of Security Council resolution 2444 (2018), we have the honour to transmit herewith the final report of the Panel of Experts on Somalia. (Signed) Jay Bahadur Coordinator Panel of Experts on Somalia (Signed) Mohamed Abdelsalam Babiker Humanitarian expert (Signed) Nazanine Moshiri Armed groups expert (Signed) Brian O’Sullivan Armed groups/natural resources expert (Signed) Matthew Rosbottom Finance expert (Signed) Richard Zabot Arms expert 2/161 19-16960 S/2019/858 Summary During the first reporting period of the Panel of Experts on Somalia, the use by Al-Shabaab of improvised explosive devices reached its greatest extent in Somali history, with a year-on-year increase of approximately one third.