Pennies Are Protons Teacher Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Confinement and Exotic Meson Spectroscopy at 12Gev JLAB

174 Brazilian Journal of Physics, vol. 33, no. 2, June, 2003 Confinement and Exotic Meson Spectroscopy at 12GeV JLAB Adam Szczepaniak Physics Department, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405, USA Received on 30 October, 2002 Phenomenology of gluonic excitations and possibilities for searches of exotic mesons at JLab are discussed. I Introduction O(104) number. For technical reasons dynamical evolu- tion is studied by replacing the Minkowski by the Euclidean Quantum chromodynamics (QCD) represents part of the metric thereby converting to a statistical systems and using Standard Model which describes the strong interactions. Monte Carlo methods to evaluate the partition function. The fundamental degrees of freedom are quarks – the mat- In parallel many analytical many-body techniques have ter fields, and gluons – the mediators of the strong force. been employed to identify effective degrees of freedom and Quarks and gluons are permanently confined into hadrons, numerous approximation schemes have been advanced to e.g. protons, neutrons and pions, to within distance scales describe the soft structure and interactions of hadrons, e.g. of the order of 1fm = 10¡15m. Hadrons are bound by the constituent quark model, bag and topological soliton residual strong forces to form atomic nuclei. Thus QCD models, QCD sum rules, chiral lagrangians, etc. determines not only the quark-gluon dynamics at the sub- In this talk I will focus on the physics of soft gluonic ex- subatomic scale but also the interactions between nuclei at citations and their role in quark confinement. Gluons carry the subatomic scale and even the nuclear dynamics at a the strong force, and since on a hadronic scale the light u and macroscopic level, e.g. -

Evolution of Intrinsic Nuclear Structure in Medium Mass Even-Even Xenon Isotopes from a Microscopic Perspective*

Chinese Physics C Vol. 44, No. 7 (2020) 074108 Evolution of intrinsic nuclear structure in medium mass even-even Xenon isotopes from a microscopic perspective* Surbhi Gupta1 Ridham Bakshi1 Suram Singh2 Arun Bharti1;1) G. H. Bhat3 J. A. Sheikh4 1Department of Physics, University of Jammu, Jammu- 180006, India 2Department of Physics and Astronomical Sciences, Central University of Jammu, Samba- 181143, India 3Department of Physics, SP College, Cluster University Srinagar- 190001, India 4Cluster University Srinagar - Jammu and Kashmir 190001, India Abstract: In this study, the multi-quasiparticle triaxial projected shell model (TPSM) is applied to investigate γ-vi- brational bands in transitional nuclei of 118−128Xe. We report that each triaxial intrinsic state has a γ-band built on it. The TPSM approach is evaluated by the comparison of TPSM results with available experimental data, which shows a satisfactory agreement. The energy ratios, B(E2) transition rates, and signature splitting of the γ-vibrational band are calculated. Keywords: triaxial projected shell model, triaxiality, yrast spectra, band diagram, back-bending, staggering, reduced transition probabilities DOI: 10.1088/1674-1137/44/7/074108 1 Introduction In the past few decades, the use of improved and sophisticated experimental techniques has made it pos- sible to provide sufficient data to describe the structure of The static and dynamic properties of a nucleus pre- nuclei in various mass regions of the nuclear chart. In dominantly dictate its shape or structure, and these prop- particular, the transitional nuclei around mass A ∼ 130 erties depend on the interactions among its constituents, have numerous interesting features, such as odd-even i.e, protons and neutrons. -

Interactions and Forces

background sheet The Standard Model 2: Interactions and forces Force Interactions The Australian Curriculum refers to fundamental In any closed system a number of properties are forces, force-carrying particles and reactions between conserved. These include energy, momentum and particles. However in this resource we have chosen charge. Although the totals of each property are to use a terminology used by contemporary particle conserved, their distribution amongst components physicists, that of interactions. of a system can change. Whenever energy (or momentum, charge or any other conserved property) The difference between ‘force’ and ‘interaction’ is is redistributed amongst components of a system subtle, but significant. Understanding it helps make then an interaction has taken place. In other words, sense of this complex study area. interactions lead to redistribution of energy, Students were probably introduced to the topic momentum and charge. of force through ‘pushes and pulls’. They learnt In Figure 1 two particles change their motion as they that changes to an object’s motion didn’t happen approach. There has been an exchange of energy and spontaneously, but were the result of some external momentum between them, so an interaction has taken action: a push or a pull. place. In this case the interaction is a consequence Later on these ideas were codified in Newton’s laws of these particles having charge, so the interaction is of motion. Together with Newton’s universal law described as electromagnetic. of gravitation, and Coulomb’s law of electrostatic Physicists recognise four fundamental interactions: interaction, changes in motion of objects could be seen as a consequence of force-pairs (action and reaction) • gravitational interaction acting between two objects. -

Probing the Quantum Universe )

July06-final.qxd 9/20/2006 9:29 PM Page 185 ARTICLE DE FOND ( PROBING THE QUANTUM UNIVERSE ) PROBING THE QUANTUM UNIVERSE by Alain Bellerive This article summarizes the activities encompassed by the the composition of our Universe, and the understanding of Particle Physics Division (PPD) at the 2006 Canadian elementary particle properties. The on-going Canadian par- Association of Physicists (CAP) annual congress that took ticipation in CLEO-c, ZEUS, D0 and CDF projects are paving place at Brock University. The summary is targeted toward the road for understanding the physics awaiting our commu- the general readership of Physics in Canada as it is meant to nity at the LHC. The knowledge gained by the future ILC be a review for non-experts in the experiments and the upcoming LHC form of a comprehensive overview of experiments is complementary since the physics research at the subatomic both facilities are needed to develop a scale. In a way the ultimate goal of A comprehensive summary more complete theory of fundamental particle physics is to establish the link of the research topics in particles and interactions. The study between our Quantum Universe and of particle properties and the probable Cosmology, and the research innova- subatomic physics and a discovery of the constituents of dark tions proposed by the PPD are critical look at the future challenges matter at accelerator complexes is for advancing this mission. The con- tightly coupled to direct investigation nection between research in particle of the Particle Physics of weakly interacting particles with physics and cosmology has never Division (PPD). -

Quest for Superheavy Nuclei Began in the 1940S with the Syn Time It Takes for Half of the Sample to Decay

FEATURES Quest for superheavy nuclei 2 P.H. Heenen l and W Nazarewicz -4 IService de Physique Nucleaire Theorique, U.L.B.-C.P.229, B-1050 Brussels, Belgium 2Department ofPhysics, University ofTennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996 3Physics Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, Tennessee 37831 4Institute ofTheoretical Physics, University ofWarsaw, ul. Ho\.za 69, PL-OO-681 Warsaw, Poland he discovery of new superheavy nuclei has brought much The superheavy elements mark the limit of nuclear mass and T excitement to the atomic and nuclear physics communities. charge; they inhabit the upper right corner of the nuclear land Hopes of finding regions of long-lived superheavy nuclei, pre scape, but the borderlines of their territory are unknown. The dicted in the early 1960s, have reemerged. Why is this search so stability ofthe superheavy elements has been a longstanding fun important and what newknowledge can it bring? damental question in nuclear science. How can they survive the Not every combination ofneutrons and protons makes a sta huge electrostatic repulsion? What are their properties? How ble nucleus. Our Earth is home to 81 stable elements, including large is the region of superheavy elements? We do not know yet slightly fewer than 300 stable nuclei. Other nuclei found in all the answers to these questions. This short article presents the nature, although bound to the emission ofprotons and neutrons, current status ofresearch in this field. are radioactive. That is, they eventually capture or emit electrons and positrons, alpha particles, or undergo spontaneous fission. Historical Background Each unstable isotope is characterized by its half-life (T1/2) - the The quest for superheavy nuclei began in the 1940s with the syn time it takes for half of the sample to decay. -

22.05 Reactor Physics – Part One Course Introduction

22.05 Reactor Physics – Part One Course Introduction 1. Instructor: John A. Bernard 2. Organization: Homework (20%) Four Exams (20% each; lowest grade is dropped) Final Exam (3.0 hours) (20%) 3. Text: The text book for this course is: Introduction to Nuclear Engineering, 3rd Edition, by John Lamarsh. This covers basic reactor physics as part of a complete survey of nuclear engineering. Readings may also be assigned from certain of the books listed below: Nuclear Reactor Analysis by A. F. Henry Introduction to Nuclear Power by G. Hewitt and J. Collier Fundamentals of Nuclear Science and Engineering by J. Shultis and R. Faw Atoms, Radiation, and Radiation Protection by J. Turner Nuclear Criticality Safety by R. Kneif Radiation Detection and Measurement by G. Knoll 4. Course Objective: To quote the late Professor Allan Henry: “The central problem of reactor physics can be stated quite simply. It is to compute, for any time t, the characteristics of the free-neutron population throughout an extended region of space containing an arbitrary, but known, mixture of materials. Specifically we wish to know the number of neutrons in any infinitesimal volume dV that have kinetic energies between E and E + ∆E and are traveling in directions within an infinitesimal angle of a fixed direction specified by the unit vector Ω. If this number is known, we can use the basic data obtained experimentally and theoretically from low-energy neutron physics to predict the rates at which all possible nuclear reactions, including fission, will take place throughout the region. Thus we can 1 predict how much nuclear power will be generated at any given time at any location in the region.” There are several reasons for needing this information: Physical understanding of reactor safety so that both design and operation is done intelligently. -

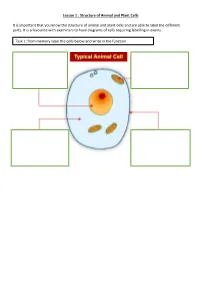

Lesson 1 : Structure of Animal and Plant Cells

Lesson 1 : Structure of Animal and Plant Cells It is important that you know the structure of animal and plant cells and are able to label the different parts. It is a favourite with examiners to have diagrams of cells requiring labelling in exams. Task 1: from memory label the cells below and write in the function Check your answers: There are many similarities and differences between animal and plant cells. Make sure you know these. Similarities Differences 1. Have a nucleus 1. Plant cells have a cellulose cell wall 2. Have a cytoplasm 2. Plant cells have a vacuole containing cell sap 3. Have a cell 3. Plant cells have chloroplast membrane 4. Contain 4. Many plant cells have a box-like shape whilst animal cell shape varies mitochondria 5. Plant cells have the nucleus to the side of the cell, animal cells have a nucleus in 5. Contain ribosomes the middle Task 2: Complete the sentences by filling in the gaps. Both plant and animal cells contain a nucleus. This holds genetic information. Both animal and plant cells have a cell membrane. This controls what enters and leaves the cell. Only a plant cell contains chloroplasts. This is where photosynthesis happens. Both cells contain mitochondria. This is where respiration occurs. Check your answers: Both plant and animal cells contain a nucleus. This holds genetic information. Both animal and plant cells have a cell membrane. This controls what enters and leaves the cell. Only a plant cell contains chloroplasts. This is where photosynthesis happens. Both cells contain mitochondria. This is where respiration occurs. -

Physics of Superheavy Elements Kouichi Hagino

Frontiers in Science II 2013.11.6 Physics of superheavy elements Kouichi Hagino Nuclear Theory Group, Department of Physics, Tohoku University What is nuclear physics? What are superheavy elements? How to create superheavy elements? What are chemical properties of superheavy elements? Introduction: atoms and atomic nuclei What would you see if you magnified the dog? ~ 50 cm Introduction: atoms and atomic nuclei cells ~ 50 cm ~ m = 10-6 m Introduction: atoms and atomic nuclei DNA cells -8 ~ 50 cm ~ m = 10-6 m ~ 10 m atom All things are made of atoms. ~ 10-10 m All things are made of atoms. • Thales, Democritus (ancient Greek) • Dalton (chemist, 19th century) • Boltzmann(19th century) • Einstein (1905) ~ 10-10 m STM image (surface physics group, Tohoku university) Introduction: atoms and atomic nuclei DNA cells -8 ~ 50 cm ~ 10 m atom atomic nucleus ~ 10-15 m ~ 10-10 m proton (+e) neutron (no charge) electron cloud (-e) Neutral atoms: # of protons = # of electrons Chemical properties of atoms # of electrons Mp ~ Mn ~ 2000 Me the mass of atom ~ the mass of nucleus Periodic table of chemical elements tabular arrangement of chemical elements based on the atomic numbers (= # of electrons = # of protons) What are we made of ? oxygen 43 kg cerium 40 mg gallium 0.7 mg carbon 16 kg barium 22 mg tellurium 0.7 mg hydrogen 7 kg iodine 20 mg yttrium 0.6 mg nitrogen 1.8 kg tin 20 mg bismuth 0.5 mg calcium 1.0 kg titanium 20 mg thallium 0.5 mg phosphorus 780 g boron 18 mg indium 0.4 mg potassium 140 g nickel 15 mg gold 0.2 mg sulphur 140 g selenium -

Section 29-4: the Chart of the Nuclides

29-4 The Chart of the Nuclides A nuclide is an atom that is characterized by what is in its nucleus. In other words, it is characterized by the number of protons it has, and by the number of neutrons it has. Figure 29.2 shows the chart of the nuclides, which plots, for stable and radioactive nuclides, the value of Z (the atomic number), on the vertical axis, and the value of N (the number of neutrons) on the horizontal axis. If you look at a horizontal line through the chart, you will find nuclides that all have the same number of protons, but a different number of neutrons. These are all nuclides of the same element, and are known as isotopes (equal proton number, different neutron number). On a vertical line through the chart, the nuclides all have the same number of neutrons, but a different number of protons. These nuclides are known as isotones (equal neutron number, different proton number). It is interesting to think about how the various decay processes play a role in the chart of the nuclides. Only the nuclides shown in black are stable. The stable nuclides give the chart a line of stability that goes from the bottom left toward the upper right, curving down and away from the Z = N line as you move toward higher N values. There are many more nuclides that are shown on the chart but which are not stable - these nuclides decay by means of a radioactive decay process. In general, the dominant decay process for a particular nuclide is the process that produces a nucleus closer to the line of stability than where it started. -

Module01 Nuclear Physics and Reactor Theory

Module I Nuclear physics and reactor theory International Atomic Energy Agency, May 2015 v1.0 Background In 1991, the General Conference (GC) in its resolution RES/552 requested the Director General to prepare 'a comprehensive proposal for education and training in both radiation protection and in nuclear safety' for consideration by the following GC in 1992. In 1992, the proposal was made by the Secretariat and after considering this proposal the General Conference requested the Director General to prepare a report on a possible programme of activities on education and training in radiological protection and nuclear safety in its resolution RES1584. In response to this request and as a first step, the Secretariat prepared a Standard Syllabus for the Post- graduate Educational Course in Radiation Protection. Subsequently, planning of specialised training courses and workshops in different areas of Standard Syllabus were also made. A similar approach was taken to develop basic professional training in nuclear safety. In January 1997, Programme Performance Assessment System (PPAS) recommended the preparation of a standard syllabus for nuclear safety based on Agency Safely Standard Series Documents and any other internationally accepted practices. A draft Standard Syllabus for Basic Professional Training Course in Nuclear Safety (BPTC) was prepared by a group of consultants in November 1997 and the syllabus was finalised in July 1998 in the second consultants meeting. The Basic Professional Training Course on Nuclear Safety was offered for the first time at the end of 1999, in English, in Saclay, France, in cooperation with Institut National des Sciences et Techniques Nucleaires/Commissariat a l'Energie Atomique (INSTN/CEA). -

IUPAC/IUPAP Provisional Report)

Pure Appl. Chem. 2018; 90(11): 1773–1832 Provisional Report Sigurd Hofmanna,*, Sergey N. Dmitrieva, Claes Fahlanderb, Jacklyn M. Gatesb, James B. Robertoa and Hideyuki Sakaib On the discovery of new elements (IUPAC/IUPAP Provisional Report) Provisional Report of the 2017 Joint Working Group of IUPAC and IUPAP https://doi.org/10.1515/pac-2018-0918 Received August 24, 2018; accepted September 24, 2018 Abstract: Almost thirty years ago the criteria that are currently used to verify claims for the discovery of a new element were set down by the comprehensive work of a Transfermium Working Group, TWG, jointly established by IUPAC and IUPAP. The recent completion of the naming of the 118 elements in the first seven periods of the Periodic Table of the Elements was considered as an opportunity for a review of these criteria in the light of the experimental and theoretical advances in the field. In late 2016 the Unions decided to estab- lish a new Joint Working Group, JWG, consisting of six members determined by the Unions. A first meeting of the JWG was in May 2017. One year later this report was finished. In a first part the works and conclusions of the TWG and the Joint Working Parties, JWP, deciding on the discovery of the now named elements are summarized. Possible experimental developments for production and identification of new elements beyond the presently known ones are estimated. Criteria and guidelines for establishing priority of discovery of these potential new elements are presented. Special emphasis is given to a description for the application of the criteria and the limits for their applicability. -

Isotonic and Isotopic Dependence of the Radiative Neutron Capture Cross-Section on the Neutron Excess

ISOTONIC AND ISOTOPIC DEPENDENCE OF THE RADIATIVE NEUTRON CAPTURE CROSS-SECTION ON THE NEUTRON EXCESS Yu. N. Trofimov V.G. Khlopin Radium Institute, Leningrad Abstract The radiative neutron capture cross-section of nuclei has been derived as a function of neutron excess on the basis of the exponential dependence of the cross-section on the reaction energy. It is shown that unknown cross-sections of stable and radioactive nuclei may be evaluated by using the isotonic and isotopic dependence together with available reference cross-section measurements. Data on fast neutron radiative capture (P3) cross-sections for medium and heavy mass nuclei are at the present time fragmentary and in some cases highly contradictory. This is particularly true of naU [1] where the error of the evaluated cross-section is 50%. The present study is a sequel to the work initiated earlier [2] on the systematic dependence of the P3 neutron cross-section on the isotope mass number, an,r(A). On the basis of the systematics of the P3 neutron cross-sections it is possible: - to reject contradictory or questionable data, and - to predict cross-section values of nuclei which are difficult to measure, including those nuclei which are radioactive. On the basis of the evaluation of P3 neutron cross-sections for nuclei of given parity (three parity groups are taken into consideration here: N and Z even-even, even-odd and odd-even nuclei), the isotopic and isotonic dependence of the cross- section can be represented by o. =K1exp(-K2 a) (1) where a - is the P3 neutron cross-section, or-(N-Z)/A - is the relative neutron excess parameter, ki,2 - are constants whose values are different for the isotopic and isotonic dependencies, and A,Z,N - are the number of protons and neutron in the nucleus.