IUPAC/IUPAP Provisional Report)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution and Understanding of the D-Block Elements in the Periodic Table Cite This: Dalton Trans., 2019, 48, 9408 Edwin C

Dalton Transactions View Article Online PERSPECTIVE View Journal | View Issue Evolution and understanding of the d-block elements in the periodic table Cite this: Dalton Trans., 2019, 48, 9408 Edwin C. Constable Received 20th February 2019, The d-block elements have played an essential role in the development of our present understanding of Accepted 6th March 2019 chemistry and in the evolution of the periodic table. On the occasion of the sesquicentenniel of the dis- DOI: 10.1039/c9dt00765b covery of the periodic table by Mendeleev, it is appropriate to look at how these metals have influenced rsc.li/dalton our understanding of periodicity and the relationships between elements. Introduction and periodic tables concerning objects as diverse as fruit, veg- etables, beer, cartoon characters, and superheroes abound in In the year 2019 we celebrate the sesquicentennial of the publi- our connected world.7 Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported Licence. cation of the first modern form of the periodic table by In the commonly encountered medium or long forms of Mendeleev (alternatively transliterated as Mendelejew, the periodic table, the central portion is occupied by the Mendelejeff, Mendeléeff, and Mendeléyev from the Cyrillic d-block elements, commonly known as the transition elements ).1 The periodic table lies at the core of our under- or transition metals. These elements have played a critical rôle standing of the properties of, and the relationships between, in our understanding of modern chemistry and have proved to the 118 elements currently known (Fig. 1).2 A chemist can look be the touchstones for many theories of valence and bonding. -

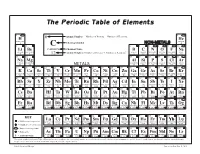

The Periodic Table of Elements

The Periodic Table of Elements 1 2 6 Atomic Number = Number of Protons = Number of Electrons HYDROGENH HELIUMHe 1 Chemical Symbol NON-METALS 4 3 4 C 5 6 7 8 9 10 Li Be CARBON Chemical Name B C N O F Ne LITHIUM BERYLLIUM = Number of Protons + Number of Neutrons* BORON CARBON NITROGEN OXYGEN FLUORINE NEON 7 9 12 Atomic Weight 11 12 14 16 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 SODIUMNa MAGNESIUMMg ALUMINUMAl SILICONSi PHOSPHORUSP SULFURS CHLORINECl ARGONAr 23 24 METALS 27 28 31 32 35 40 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 POTASSIUMK CALCIUMCa SCANDIUMSc TITANIUMTi VANADIUMV CHROMIUMCr MANGANESEMn FeIRON COBALTCo NICKELNi CuCOPPER ZnZINC GALLIUMGa GERMANIUMGe ARSENICAs SELENIUMSe BROMINEBr KRYPTONKr 39 40 45 48 51 52 55 56 59 59 64 65 70 73 75 79 80 84 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 RUBIDIUMRb STRONTIUMSr YTTRIUMY ZIRCONIUMZr NIOBIUMNb MOLYBDENUMMo TECHNETIUMTc RUTHENIUMRu RHODIUMRh PALLADIUMPd AgSILVER CADMIUMCd INDIUMIn SnTIN ANTIMONYSb TELLURIUMTe IODINEI XeXENON 85 88 89 91 93 96 98 101 103 106 108 112 115 119 122 128 127 131 55 56 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 CESIUMCs BARIUMBa HAFNIUMHf TANTALUMTa TUNGSTENW RHENIUMRe OSMIUMOs IRIDIUMIr PLATINUMPt AuGOLD MERCURYHg THALLIUMTl PbLEAD BISMUTHBi POLONIUMPo ASTATINEAt RnRADON 133 137 178 181 184 186 190 192 195 197 201 204 207 209 209 210 222 87 88 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 FRANCIUMFr RADIUMRa RUTHERFORDIUMRf DUBNIUMDb SEABORGIUMSg BOHRIUMBh HASSIUMHs MEITNERIUMMt DARMSTADTIUMDs ROENTGENIUMRg COPERNICIUMCn NIHONIUMNh -

An Octad for Darmstadtium and Excitement for Copernicium

SYNOPSIS An Octad for Darmstadtium and Excitement for Copernicium The discovery that copernicium can decay into a new isotope of darmstadtium and the observation of a previously unseen excited state of copernicium provide clues to the location of the “island of stability.” By Katherine Wright holy grail of nuclear physics is to understand the stability uncover its position. of the periodic table’s heaviest elements. The problem Ais, these elements only exist in the lab and are hard to The team made their discoveries while studying the decay of make. In an experiment at the GSI Helmholtz Center for Heavy isotopes of flerovium, which they created by hitting a plutonium Ion Research in Germany, researchers have now observed a target with calcium ions. In their experiments, flerovium-288 previously unseen isotope of the heavy element darmstadtium (Z = 114, N = 174) decayed first into copernicium-284 and measured the decay of an excited state of an isotope of (Z = 112, N = 172) and then into darmstadtium-280 (Z = 110, another heavy element, copernicium [1]. The results could N = 170), a previously unseen isotope. They also measured an provide “anchor points” for theories that predict the stability of excited state of copernicium-282, another isotope of these heavy elements, says Anton Såmark-Roth, of Lund copernicium. Copernicium-282 is interesting because it University in Sweden, who helped conduct the experiments. contains an even number of protons and neutrons, and researchers had not previously measured an excited state of a A nuclide’s stability depends on how many protons (Z) and superheavy even-even nucleus, Såmark-Roth says. -

The Oganesson Odyssey Kit Chapman Explores the Voyage to the Discovery of Element 118, the Pioneer Chemist It Is Named After, and False Claims Made Along the Way

in your element The oganesson odyssey Kit Chapman explores the voyage to the discovery of element 118, the pioneer chemist it is named after, and false claims made along the way. aving an element named after you Ninov had been dismissed from Berkeley for is incredibly rare. In fact, to be scientific misconduct in May5, and had filed Hhonoured in this manner during a grievance procedure6. your lifetime has only happened to Today, the discovery of the last element two scientists — Glenn Seaborg and of the periodic table as we know it is Yuri Oganessian. Yet, on meeting Oganessian undisputed, but its structure and properties it seems fitting. A colleague of his once remain a mystery. No chemistry has been told me that when he first arrived in the performed on this radioactive giant: 294Og halls of Oganessian’s programme at the has a half-life of less than a millisecond Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR) before it succumbs to α -decay. in Dubna, Russia, it was unlike anything Theoretical models however suggest it he’d ever experienced. Forget the 2,000 ton may not conform to the periodic trends. As magnets, the beam lines and the brand new a noble gas, you would expect oganesson cyclotron being installed designed to hunt to have closed valence shells, ending with for elements 119 and 120, the difference a filled 7s27p6 configuration. But in 2017, a was Oganessian: “When you come to work US–New Zealand collaboration predicted for Yuri, it’s not like a lab,” he explained. that isn’t the case7. -

IUPAC Wire See Also

News and information on IUPAC, its fellows, and member organizations. IUPAC Wire See also www.iupac.org Flerovium and Livermorium Join the Future Earth: Research for Global Periodic Table Sustainability n 30 May 2012, IUPAC officially approved he International Council for Science (ICSU), of the name flerovium, with symbol Fl, for the which IUPAC is a member, announced a new Oelement of atomic number 114 and the name T10-year initiative named Future Earth to unify livermorium, with symbol Lv, for the element of atomic and scale up ICSU-sponsored global environmental- number 116. The names and symbols were proposed change research. by the collaborating team of the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (Dubna, Russia) and the Lawrence Operational in 2013, this new ICSU initiative will Livermore National Laboratory (Livermore, California, provide a cutting-edge platform to coordinate scien- USA) to whom the priority for the discovery of these tific research to respond to the most critical social and elements was assigned last year. The IUPAC recom- environmental challenges of the 21st century at global mendations presenting these names is to appear in and regional levels. “This initiative will link global envi- the July 2012 issue of Pure and Applied Chemistry. ronmental change and fundamental human develop- ment questions,” said Diana Liverman, co-director of The name flerovium, with symbol Fl, lies within the Institute of the Environment at the University of tradition and honors the Flerov Laboratory of Nuclear Arizona and co-chair of the team Reactions in Dubna, Russia, where the element of that is designing Future Earth. -

Evolution of Intrinsic Nuclear Structure in Medium Mass Even-Even Xenon Isotopes from a Microscopic Perspective*

Chinese Physics C Vol. 44, No. 7 (2020) 074108 Evolution of intrinsic nuclear structure in medium mass even-even Xenon isotopes from a microscopic perspective* Surbhi Gupta1 Ridham Bakshi1 Suram Singh2 Arun Bharti1;1) G. H. Bhat3 J. A. Sheikh4 1Department of Physics, University of Jammu, Jammu- 180006, India 2Department of Physics and Astronomical Sciences, Central University of Jammu, Samba- 181143, India 3Department of Physics, SP College, Cluster University Srinagar- 190001, India 4Cluster University Srinagar - Jammu and Kashmir 190001, India Abstract: In this study, the multi-quasiparticle triaxial projected shell model (TPSM) is applied to investigate γ-vi- brational bands in transitional nuclei of 118−128Xe. We report that each triaxial intrinsic state has a γ-band built on it. The TPSM approach is evaluated by the comparison of TPSM results with available experimental data, which shows a satisfactory agreement. The energy ratios, B(E2) transition rates, and signature splitting of the γ-vibrational band are calculated. Keywords: triaxial projected shell model, triaxiality, yrast spectra, band diagram, back-bending, staggering, reduced transition probabilities DOI: 10.1088/1674-1137/44/7/074108 1 Introduction In the past few decades, the use of improved and sophisticated experimental techniques has made it pos- sible to provide sufficient data to describe the structure of The static and dynamic properties of a nucleus pre- nuclei in various mass regions of the nuclear chart. In dominantly dictate its shape or structure, and these prop- particular, the transitional nuclei around mass A ∼ 130 erties depend on the interactions among its constituents, have numerous interesting features, such as odd-even i.e, protons and neutrons. -

Gas-Phase Chemistry of Element 114, Flerovium

EPJ Web of Conferences 131, 07003 (2016) DOI: 10.1051/epjconf/201613107003 Nobel Symposium NS160 – Chemistry and Physics of Heavy and Superheavy Elements Gas-phase chemistry of element 114, flerovium Alexander Yakushev1,2,a and Robert Eichler3,4 1 GSI Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung GmbH, 64291 Darmstadt, Germany 2 Helmholtz-Institut Mainz, 55099 Mainz, Germany 3 Paul Scherrer Institut, 5232 Villigen PSI, Switzerland 4 University of Bern, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, 3012 Bern, Switzerland Abstract. Element 114 was discovered in 2000 by the Dubna-Livermore collaboration, and in 2012 it was named flerovium. It belongs to the group 14 of the periodic table of elements. A strong relativistic stabilisation of 2 2 the valence shell 7s 7p1/2 is expected due to the orbital splitting and the 2 2 contraction not only of the 7s but also of the spherical 7p1/2 closed subshell, resulting in the enhanced volatility and inertness. Flerovium was studied chemically by gas-solid chromatography upon its adsorption on a gold surface. Two experimental results on Fl chemistry have been published so far. Based on observation of three atoms, a weak interaction of flerovium with gold was suggested in the first study. Authors of the second study concluded on the metallic character after the observation of two Fl atoms deposited on gold at room temperature. 1. Introduction Man-made superheavy elements (SHE, atomic number Z ≥ 104) are unique in two aspects. Their nuclei exist only due to nuclear shell effects, and their electron structure is influenced by increasingly important relativistic effects [1–3]. Recently the synthesis of elements 113, 115, 117 and 118 has been approved, thus, the discovery of all elements of the 7th row in the periodic table of elements with proton number Z up to 118 has been acknowledged [4]. -

Quest for Superheavy Nuclei Began in the 1940S with the Syn Time It Takes for Half of the Sample to Decay

FEATURES Quest for superheavy nuclei 2 P.H. Heenen l and W Nazarewicz -4 IService de Physique Nucleaire Theorique, U.L.B.-C.P.229, B-1050 Brussels, Belgium 2Department ofPhysics, University ofTennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996 3Physics Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, Tennessee 37831 4Institute ofTheoretical Physics, University ofWarsaw, ul. Ho\.za 69, PL-OO-681 Warsaw, Poland he discovery of new superheavy nuclei has brought much The superheavy elements mark the limit of nuclear mass and T excitement to the atomic and nuclear physics communities. charge; they inhabit the upper right corner of the nuclear land Hopes of finding regions of long-lived superheavy nuclei, pre scape, but the borderlines of their territory are unknown. The dicted in the early 1960s, have reemerged. Why is this search so stability ofthe superheavy elements has been a longstanding fun important and what newknowledge can it bring? damental question in nuclear science. How can they survive the Not every combination ofneutrons and protons makes a sta huge electrostatic repulsion? What are their properties? How ble nucleus. Our Earth is home to 81 stable elements, including large is the region of superheavy elements? We do not know yet slightly fewer than 300 stable nuclei. Other nuclei found in all the answers to these questions. This short article presents the nature, although bound to the emission ofprotons and neutrons, current status ofresearch in this field. are radioactive. That is, they eventually capture or emit electrons and positrons, alpha particles, or undergo spontaneous fission. Historical Background Each unstable isotope is characterized by its half-life (T1/2) - the The quest for superheavy nuclei began in the 1940s with the syn time it takes for half of the sample to decay. -

22.05 Reactor Physics – Part One Course Introduction

22.05 Reactor Physics – Part One Course Introduction 1. Instructor: John A. Bernard 2. Organization: Homework (20%) Four Exams (20% each; lowest grade is dropped) Final Exam (3.0 hours) (20%) 3. Text: The text book for this course is: Introduction to Nuclear Engineering, 3rd Edition, by John Lamarsh. This covers basic reactor physics as part of a complete survey of nuclear engineering. Readings may also be assigned from certain of the books listed below: Nuclear Reactor Analysis by A. F. Henry Introduction to Nuclear Power by G. Hewitt and J. Collier Fundamentals of Nuclear Science and Engineering by J. Shultis and R. Faw Atoms, Radiation, and Radiation Protection by J. Turner Nuclear Criticality Safety by R. Kneif Radiation Detection and Measurement by G. Knoll 4. Course Objective: To quote the late Professor Allan Henry: “The central problem of reactor physics can be stated quite simply. It is to compute, for any time t, the characteristics of the free-neutron population throughout an extended region of space containing an arbitrary, but known, mixture of materials. Specifically we wish to know the number of neutrons in any infinitesimal volume dV that have kinetic energies between E and E + ∆E and are traveling in directions within an infinitesimal angle of a fixed direction specified by the unit vector Ω. If this number is known, we can use the basic data obtained experimentally and theoretically from low-energy neutron physics to predict the rates at which all possible nuclear reactions, including fission, will take place throughout the region. Thus we can 1 predict how much nuclear power will be generated at any given time at any location in the region.” There are several reasons for needing this information: Physical understanding of reactor safety so that both design and operation is done intelligently. -

Lesson 1 : Structure of Animal and Plant Cells

Lesson 1 : Structure of Animal and Plant Cells It is important that you know the structure of animal and plant cells and are able to label the different parts. It is a favourite with examiners to have diagrams of cells requiring labelling in exams. Task 1: from memory label the cells below and write in the function Check your answers: There are many similarities and differences between animal and plant cells. Make sure you know these. Similarities Differences 1. Have a nucleus 1. Plant cells have a cellulose cell wall 2. Have a cytoplasm 2. Plant cells have a vacuole containing cell sap 3. Have a cell 3. Plant cells have chloroplast membrane 4. Contain 4. Many plant cells have a box-like shape whilst animal cell shape varies mitochondria 5. Plant cells have the nucleus to the side of the cell, animal cells have a nucleus in 5. Contain ribosomes the middle Task 2: Complete the sentences by filling in the gaps. Both plant and animal cells contain a nucleus. This holds genetic information. Both animal and plant cells have a cell membrane. This controls what enters and leaves the cell. Only a plant cell contains chloroplasts. This is where photosynthesis happens. Both cells contain mitochondria. This is where respiration occurs. Check your answers: Both plant and animal cells contain a nucleus. This holds genetic information. Both animal and plant cells have a cell membrane. This controls what enters and leaves the cell. Only a plant cell contains chloroplasts. This is where photosynthesis happens. Both cells contain mitochondria. This is where respiration occurs. -

No. It's Livermorium!

in your element Uuh? No. It’s livermorium! Alpha decay into flerovium? It must be Lv, saysKat Day, as she tells us how little we know about element 116. t the end of last year, the International behaviour in polonium, which we’d expect to Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry have very similar chemistry. The most stable A(IUPAC) announced the verification class of polonium compounds are polonides, of the discoveries of four new chemical for example Na2Po (ref. 8), so in theory elements, 113, 115, 117 and 118, thus Na2Lv and its analogues should be attainable, completing period 7 of the periodic table1. though they are yet to be synthesized. Though now named2 (no doubt after having Experiments carried out in 2011 showed 3 213 212m read the Sceptical Chymist blog post ), that the hydrides BiH3 and PoH2 were 9 we shall wait until the public consultation surprisingly thermally stable . LvH2 would period is over before In Your Element visits be expected to be less stable than the much these ephemeral entities. lighter polonium hydride, but its chemical In the meantime, what do we know of investigation might be possible in the gas their close neighbour, element 116? Well, after phase, if a sufficiently stable isotope can a false start4, the element was first legitimately be found. reported in 2000 by a collaborative team Despite the considerable challenges posed following experiments at the Joint Institute for by the short-lived nature of livermorium, EMMA SOFIA KARLSSON, STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN STOCKHOLM, KARLSSON, EMMA SOFIA Nuclear Research (JINR) in Dubna, Russia. -

Periodic Table 1 Periodic Table

Periodic table 1 Periodic table This article is about the table used in chemistry. For other uses, see Periodic table (disambiguation). The periodic table is a tabular arrangement of the chemical elements, organized on the basis of their atomic numbers (numbers of protons in the nucleus), electron configurations , and recurring chemical properties. Elements are presented in order of increasing atomic number, which is typically listed with the chemical symbol in each box. The standard form of the table consists of a grid of elements laid out in 18 columns and 7 Standard 18-column form of the periodic table. For the color legend, see section Layout, rows, with a double row of elements under the larger table. below that. The table can also be deconstructed into four rectangular blocks: the s-block to the left, the p-block to the right, the d-block in the middle, and the f-block below that. The rows of the table are called periods; the columns are called groups, with some of these having names such as halogens or noble gases. Since, by definition, a periodic table incorporates recurring trends, any such table can be used to derive relationships between the properties of the elements and predict the properties of new, yet to be discovered or synthesized, elements. As a result, a periodic table—whether in the standard form or some other variant—provides a useful framework for analyzing chemical behavior, and such tables are widely used in chemistry and other sciences. Although precursors exist, Dmitri Mendeleev is generally credited with the publication, in 1869, of the first widely recognized periodic table.