22.05 Reactor Physics – Part One Course Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution of Intrinsic Nuclear Structure in Medium Mass Even-Even Xenon Isotopes from a Microscopic Perspective*

Chinese Physics C Vol. 44, No. 7 (2020) 074108 Evolution of intrinsic nuclear structure in medium mass even-even Xenon isotopes from a microscopic perspective* Surbhi Gupta1 Ridham Bakshi1 Suram Singh2 Arun Bharti1;1) G. H. Bhat3 J. A. Sheikh4 1Department of Physics, University of Jammu, Jammu- 180006, India 2Department of Physics and Astronomical Sciences, Central University of Jammu, Samba- 181143, India 3Department of Physics, SP College, Cluster University Srinagar- 190001, India 4Cluster University Srinagar - Jammu and Kashmir 190001, India Abstract: In this study, the multi-quasiparticle triaxial projected shell model (TPSM) is applied to investigate γ-vi- brational bands in transitional nuclei of 118−128Xe. We report that each triaxial intrinsic state has a γ-band built on it. The TPSM approach is evaluated by the comparison of TPSM results with available experimental data, which shows a satisfactory agreement. The energy ratios, B(E2) transition rates, and signature splitting of the γ-vibrational band are calculated. Keywords: triaxial projected shell model, triaxiality, yrast spectra, band diagram, back-bending, staggering, reduced transition probabilities DOI: 10.1088/1674-1137/44/7/074108 1 Introduction In the past few decades, the use of improved and sophisticated experimental techniques has made it pos- sible to provide sufficient data to describe the structure of The static and dynamic properties of a nucleus pre- nuclei in various mass regions of the nuclear chart. In dominantly dictate its shape or structure, and these prop- particular, the transitional nuclei around mass A ∼ 130 erties depend on the interactions among its constituents, have numerous interesting features, such as odd-even i.e, protons and neutrons. -

1 Phys:1200 Lecture 36 — Atomic and Nuclear Physics

1 PHYS:1200 LECTURE 36 — ATOMIC AND NUCLEAR PHYSICS (4) This last lecture of the course will focus on nuclear energy. There is an enormous reservoir of energy in the nucleus and it can be released either in a controlled manner in a nuclear reactor, or in an uncontrolled manner in a nuclear bomb. The energy released in a nuclear reactor can be used to produce electricity. The two processes in which nuclear energy is released – nuclear fission and nuclear fusion, will be discussed in this lecture. The biological effects of nuclear radiation will also be discussed. 36‐1. Biological Effects of Nuclear Radiation.—Radioactive nuclei emit alpha, beta, and gamma radiation. These radiations are harmful to humans because they are ionizing radiation that have the ability to remove electrons from atoms and molecules in human cells. This can lead to the death or alterations of cells. Alteration of the cell can transform a healthy cell into a cancer cell. The hazards of radiation can be minimized by limiting ones overall exposure to radiation. However, there is still some uncertainty in the medical community about the possibility the effect of a single radioactive particle on the bottom. In other words, are the effects cumulative, or can a single exposure lead to cancer in the body. Exposure to radiation can produce either short term effects appearing within minutes of exposure, or long term effects that may appear in years or decades or even in future generations due to changes in DNA. The effects of absorbing ionizing radiation is measured in a unit called the rem. -

Enrico Fermi

Fermi, Enrico Inventors and Inventions Enrico Fermi Italian American physicist Fermi helped develop Fermi-Dirac statistics, which liceo (secondary school) and, on the advice of Amidei, elucidate the group behavior of elementary particles. joined the Scuola Normale Superiore at Pisa. This elite He also developed the theory of beta decay and college, attached to the University of Pisa, admitted only discovered neutron-induced artificial radioactivity. forty of Italy’s top students, who were given free board Finally, he succeeded in producing the first sustained and lodging. Fermi performed exceedingly well in the nuclear chain reaction, which led to the discovery highly competitive entrance exam. He completed his of nuclear energy and the development of the university education after only four years of research and atomic bomb. studies, receiving his Ph.D. in physics from the Univer- sity of Pisa and his undergraduate diploma from the Born: September 29, 1901; Rome, Italy Scuola Normale Superiore in July, 1922. He became Died: November 28, 1954; Chicago, Illinois an expert theoretical physicist and a talented exper- Primary field: Physics imentalist. This rare combination provided a solid foun- Primary inventions: Controlled nuclear chain dation for all his subsequent inventions. reaction; Fermi-Dirac statistics; theory of beta decay Life’s Work After postdoctoral work at the University of Göttingen, Early Life in Germany (1922-1923), and the University of Leiden, Enrico Fermi (ehn-REE-koh FUR-mee) was the third in the Netherlands (fall, 1924), Fermi took an interim po- child of Alberto Fermi and Ida de Gattis. Enrico was very sition at the University of Florence in December, 1924. -

Nuclear Weapons Technology 101 for Policy Wonks Bruce T

NUCLEAR WEAPONS TECHNOLOGY FOR POLICY WONKS NUCLEAR WEAPONS TECHNOLOGY 101 FOR POLICY WONKS BRUCE T. GOODWIN BRUCE T. GOODWIN BRUCE T. Center for Global Security Research Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory August 2021 NUCLEAR WEAPONS TECHNOLOGY 101 FOR POLICY WONKS BRUCE T. GOODWIN Center for Global Security Research Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory August 2021 NUCLEAR WEAPONS TECHNOLOGY 101 FOR POLICY WONKS | 1 This work was performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in part under Contract W-7405-Eng-48 and in part under Contract DE-AC52-07NA27344. The views and opinions of the author expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States government or Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC. ISBN-978-1-952565-11-3 LCCN-2021907474 LLNL-MI-823628 TID-61681 2 | BRUCE T. GOODWIN Table of Contents About the Author. 2 Introduction . .3 The Revolution in Physics That Led to the Bomb . 4 The Nuclear Arms Race Begins. 6 Fission and Fusion are "Natural" Processes . 7 The Basics of the Operation of Nuclear Explosives. 8 The Atom . .9 Isotopes . .9 Half-life . 10 Fission . 10 Chain Reaction . 11 Critical Mass . 11 Fusion . 14 Types of Nuclear Weapons . 16 Finally, How Nuclear Weapons Work . 19 Fission Explosives . 19 Fusion Explosives . 22 Staged Thermonuclear Explosives: the H-bomb . 23 The Modern, Miniature Hydrogen Bomb . 25 Intrinsically Safe Nuclear Weapons . 32 Underground Testing . 35 The End of Nuclear Testing and the Advent of Science-Based Stockpile Stewardship . 39 Stockpile Stewardship Today . 41 Appendix 1: The Nuclear Weapons Complex . -

Quest for Superheavy Nuclei Began in the 1940S with the Syn Time It Takes for Half of the Sample to Decay

FEATURES Quest for superheavy nuclei 2 P.H. Heenen l and W Nazarewicz -4 IService de Physique Nucleaire Theorique, U.L.B.-C.P.229, B-1050 Brussels, Belgium 2Department ofPhysics, University ofTennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996 3Physics Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, Tennessee 37831 4Institute ofTheoretical Physics, University ofWarsaw, ul. Ho\.za 69, PL-OO-681 Warsaw, Poland he discovery of new superheavy nuclei has brought much The superheavy elements mark the limit of nuclear mass and T excitement to the atomic and nuclear physics communities. charge; they inhabit the upper right corner of the nuclear land Hopes of finding regions of long-lived superheavy nuclei, pre scape, but the borderlines of their territory are unknown. The dicted in the early 1960s, have reemerged. Why is this search so stability ofthe superheavy elements has been a longstanding fun important and what newknowledge can it bring? damental question in nuclear science. How can they survive the Not every combination ofneutrons and protons makes a sta huge electrostatic repulsion? What are their properties? How ble nucleus. Our Earth is home to 81 stable elements, including large is the region of superheavy elements? We do not know yet slightly fewer than 300 stable nuclei. Other nuclei found in all the answers to these questions. This short article presents the nature, although bound to the emission ofprotons and neutrons, current status ofresearch in this field. are radioactive. That is, they eventually capture or emit electrons and positrons, alpha particles, or undergo spontaneous fission. Historical Background Each unstable isotope is characterized by its half-life (T1/2) - the The quest for superheavy nuclei began in the 1940s with the syn time it takes for half of the sample to decay. -

Memorandum to Participants JASON 1994 Summer Study

Hydronnclear Testing and the Comprehensive Test Ban: Memorandum to Participants JASON 1994 Summer Study Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. 1350 New York Avenue, NW, Suite 300 Washington, D.C. 20005 Tel (main): (202) 783-7800 Cochran (direct dial): (202) 624-9329 Paine (direct dial): (202) 624-9350 Fax: (202) 783-5917 INTERNET: [email protected] Although no commonly accepted defInition exists, a "hydronuclear test" may be generally described as a nuclear weapons test, or high-explosive driven criticality experiment, characterized by a nuclear energy release that is insuffIcient to heat the core material to the plasma temperatures that would cause it to explode "like a bomb." In such a test, the TNT equivalent energy release from fission would therefore not exceed the amount released by the chemical high explosive used to compress the fIssile material, and could be considerably ,less. Nuclear-weapon states, and possibly other states, also perform high-explosive driven implosion experiments using fusjon material, although" these' are not nonnally characterized as "hydronuclear tests". Hydronuclear tests can serve a useful role in the development of the full spectrum of unboosted fIssion weapons, including'first generation nuclear weapons of the implosion type with yields in the 5 to 30 kiloton range, more sophisticated designs with yields up to about a megaton, and advanced micro-nuclear weapons with yields of 5 to 500 tons. For pure fIssion weapons hydronuclear tests can be used to:' * optimize the timing of initiation of the -

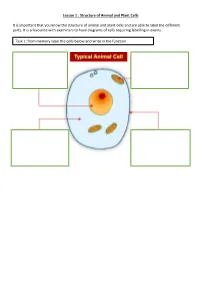

Lesson 1 : Structure of Animal and Plant Cells

Lesson 1 : Structure of Animal and Plant Cells It is important that you know the structure of animal and plant cells and are able to label the different parts. It is a favourite with examiners to have diagrams of cells requiring labelling in exams. Task 1: from memory label the cells below and write in the function Check your answers: There are many similarities and differences between animal and plant cells. Make sure you know these. Similarities Differences 1. Have a nucleus 1. Plant cells have a cellulose cell wall 2. Have a cytoplasm 2. Plant cells have a vacuole containing cell sap 3. Have a cell 3. Plant cells have chloroplast membrane 4. Contain 4. Many plant cells have a box-like shape whilst animal cell shape varies mitochondria 5. Plant cells have the nucleus to the side of the cell, animal cells have a nucleus in 5. Contain ribosomes the middle Task 2: Complete the sentences by filling in the gaps. Both plant and animal cells contain a nucleus. This holds genetic information. Both animal and plant cells have a cell membrane. This controls what enters and leaves the cell. Only a plant cell contains chloroplasts. This is where photosynthesis happens. Both cells contain mitochondria. This is where respiration occurs. Check your answers: Both plant and animal cells contain a nucleus. This holds genetic information. Both animal and plant cells have a cell membrane. This controls what enters and leaves the cell. Only a plant cell contains chloroplasts. This is where photosynthesis happens. Both cells contain mitochondria. This is where respiration occurs. -

Physics of Superheavy Elements Kouichi Hagino

Frontiers in Science II 2013.11.6 Physics of superheavy elements Kouichi Hagino Nuclear Theory Group, Department of Physics, Tohoku University What is nuclear physics? What are superheavy elements? How to create superheavy elements? What are chemical properties of superheavy elements? Introduction: atoms and atomic nuclei What would you see if you magnified the dog? ~ 50 cm Introduction: atoms and atomic nuclei cells ~ 50 cm ~ m = 10-6 m Introduction: atoms and atomic nuclei DNA cells -8 ~ 50 cm ~ m = 10-6 m ~ 10 m atom All things are made of atoms. ~ 10-10 m All things are made of atoms. • Thales, Democritus (ancient Greek) • Dalton (chemist, 19th century) • Boltzmann(19th century) • Einstein (1905) ~ 10-10 m STM image (surface physics group, Tohoku university) Introduction: atoms and atomic nuclei DNA cells -8 ~ 50 cm ~ 10 m atom atomic nucleus ~ 10-15 m ~ 10-10 m proton (+e) neutron (no charge) electron cloud (-e) Neutral atoms: # of protons = # of electrons Chemical properties of atoms # of electrons Mp ~ Mn ~ 2000 Me the mass of atom ~ the mass of nucleus Periodic table of chemical elements tabular arrangement of chemical elements based on the atomic numbers (= # of electrons = # of protons) What are we made of ? oxygen 43 kg cerium 40 mg gallium 0.7 mg carbon 16 kg barium 22 mg tellurium 0.7 mg hydrogen 7 kg iodine 20 mg yttrium 0.6 mg nitrogen 1.8 kg tin 20 mg bismuth 0.5 mg calcium 1.0 kg titanium 20 mg thallium 0.5 mg phosphorus 780 g boron 18 mg indium 0.4 mg potassium 140 g nickel 15 mg gold 0.2 mg sulphur 140 g selenium -

Cm Element of the Day Curium (Kewreeәm) Is a Transuranic Radioactive Chemical Element with the Symbol Cm and Atomic Number 96

Cm Element of the Day Curium (kewreeәm) is a transuranic radioactive chemical element with the symbol Cm and atomic number 96. This element of the actinide series was named after Marie Curie and her husband Pierre Curie both were known for their research on radioactivity. Most curium is produced by bombarding uranium or plutonium with neutrons in nuclear reactors – one ton of spent nuclear fuel contains about 20 grams of curium. Curium is a hard, dense, silvery metal with a relatively high melting point and boiling point for an actinide. Curium readily oxidizes, and its oxides are a dominant form of this element. When introduced into the human body, curium accumulates in the bones, lungs and liver, where it promotes cancer. All known isotopes of curium are radioactive and have a small critical mass for a sustained nuclear chain reaction. Curium is used in production of heavier actinides and of the 238Pu radionuclide for power sources in artificial pacemakers. It served as the α source in the alpha particle Xray spectrometers used to analyze rock composition. Curium's outer electrons have a principal quantum level of four. How many electrons may fit into this orbital? 1 Chemistry 1. WarmUp 5 2. Review Book Homework 10 3. Notes 20 4. Complete POGIL Activity 30 5. Test Review 20 Announcements Due Today: Mole Airlines Extra Credit Due Today: Read pages 317 to 331 and answer questions 1 9 odd, 15, 17, 19 and 25. Begin work on Study Guide! Will be available after school today. Semester Review Session Thursday at 3:00 pm 2 Homework Review 3 POGIL Activity with Modeling Kits! Turn in 4 Review/Notes 5 Quantum Numbers Review Questions 1. -

Highly Enriched Uranium: Striking a Balance

OFFICIAL USE ONLY - DRAFT GLOSSARY OF TERMS APPENDIX F GLOSSARY OF TERMS Accountability: That part of the safeguards and security program that encompasses the measurement and inventory verification systems, records, and reports to account for nuclear materials. Assay: Measurement that establishes the total quantity of the isotope of an element and the total quantity of that element. Atom: The basic component of all matter. Atoms are the smallest part of an element that have all of the chemical properties of that element. Atoms consist of a nucleus of protons and neutrons surrounded by electrons. Atomic energy: All forms of energy released in the course of nuclear fission or nuclear transformation. Atomic weapon: Any device utilizing atomic energy, exclusive of the means for transportation or propelling the device (where such means is a separable and divisible part of the device), the principal purpose of which is for use as, or for development of, a weapon, a weapon prototype, or a weapon test device. Blending: The intentional mixing of two different assays of the same material in order to achieve a desired third assay. Book inventory: The quantity of nuclear material present at a given time as reflected by accounting records. Burnup: A measure of consumption of fissionable material in reactor fuel. Burnup can be expressed as (a) the percentage of fissionable atoms that have undergone fission or capture, or (b) the amount of energy produced per unit weight of fuel in the reactor. Chain reaction: A self-sustaining series of nuclear fission reactions. Neutrons produced by fission cause more fission. Chain reactions are essential to the functioning of nuclear reactors and weapons. -

Section 29-4: the Chart of the Nuclides

29-4 The Chart of the Nuclides A nuclide is an atom that is characterized by what is in its nucleus. In other words, it is characterized by the number of protons it has, and by the number of neutrons it has. Figure 29.2 shows the chart of the nuclides, which plots, for stable and radioactive nuclides, the value of Z (the atomic number), on the vertical axis, and the value of N (the number of neutrons) on the horizontal axis. If you look at a horizontal line through the chart, you will find nuclides that all have the same number of protons, but a different number of neutrons. These are all nuclides of the same element, and are known as isotopes (equal proton number, different neutron number). On a vertical line through the chart, the nuclides all have the same number of neutrons, but a different number of protons. These nuclides are known as isotones (equal neutron number, different proton number). It is interesting to think about how the various decay processes play a role in the chart of the nuclides. Only the nuclides shown in black are stable. The stable nuclides give the chart a line of stability that goes from the bottom left toward the upper right, curving down and away from the Z = N line as you move toward higher N values. There are many more nuclides that are shown on the chart but which are not stable - these nuclides decay by means of a radioactive decay process. In general, the dominant decay process for a particular nuclide is the process that produces a nucleus closer to the line of stability than where it started. -

Nuclear Power

MORE CHAPTER 11, #6 Nuclear Power Nuclear Fission Reactors The discovery that several neutrons are emitted in the fission process led to specula- tion concerning the possibility of using these neutrons to initiate other fissions, thereby producing a chain reaction. On December 2, 1942, less than four years after Hahn and Strassmann’s discovery of fission, a group led by Enrico Fermi produced the first self-sustaining chain reaction in a nuclear reactor that they had constructed at the University of Chicago.24 To sustain a chain reaction in a fission reactor, one of the neutrons (on the average) emitted in the fission of 235U must be captured by another 235U nucleus and cause it to fission. The reproduction factor k of a reactor is defined as the average number of neutrons from each fission that cause a subsequent fission. In the case of 235U the maximum possible value of k is about 2.4, but it is normally less than this for two important reasons: (1) some of the neutrons may escape from the region contain- ing fissionable nuclei, and (2) some of the neutrons may be captured by nonfissioning nuclei in the reactor. If k is exactly 1, the reaction will be self-sustaining. If it is less than 1, the reaction will die out. If k is significantly greater than 1, the reaction rate will increase rapidly and “run away.” In the design of nuclear bombs, such a runaway reaction is necessary. In power reactors, the value of k must be kept very nearly equal to 1 (see Figure 11-50).