EDWARDIAN FASHION Daniel Milford-Cottam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evening Gown Sewing Supplies Embroidering on Lightweight Silk Satin

Evening Gown Sewing supplies Embroidering on lightweight silk satin The deLuxe Stitch System™ improves the correct balance • HUSQVARNA VIKING® DESIGNER DIAMOND between needle thread and bobbin thread. Thanks to the deLuxe™ sewing and embroidery machine deLuxe Stitch System™ you can now easily embroider • HUSQVARNA VIKING® HUSKYLOCK™ overlock with different kinds of threads in the same design. machine. • Use an Inspira® embroidery needle, size 75 • Pattern for your favourite strap dress. • Turquoise sand-washed silk satin. • Always test your embroidery on scraps of the actual fabric with the stabilizer and threads you will be using • Dark turquoise fabric for applique. before starting your project. • DESIGNER DIAMOND deLuxe™ sewing and • Hoop the fabric with tear-away stabilizer underneath embroidery machine Sampler Designs #1, 2, 3, 4, 5. and if the fabric needs more support use two layers of • HUSQVARNA VIKING® DESIGNER™ Royal Hoop tear-away stabilizer underneath the fabric. 360 x 200, #412 94 45-01 • Endless Embroidery Hoop 180 x 100, #920 051 096 Embroider and Sew • Inspira® Embroidery Needle, size 75 • To insure a good fit, first sew the dress in muslin or • Inspira® Tear-A-Way Stabilizer another similar fabric and make the changes before • Water-Soluble Stabilizer you start to cut and sew in the fashion fabric for the dress. • Various blue embroidery thread Rayon 40 wt • Sulky® Sliver thread • For the bodice front and back pieces you need to embroider the fabric before cutting the pieces. Trace • Metallic thread out the pattern pieces on the fabric so you will know how much area to fill with embroidery design #1. -

Evening Gown Quilt Mystique

Evening Gown FREE PROJECT SHEET • 888.768.8454 • 468 West Universal Circle Sandy, UT 84070 • www.rileyblakedesigns.com FINISHED QUILT SIZE 56” x 60” Border 1 Measurements include ¼” seam allowance. Cut 5 strips 5½” x WOF from black main Sew with right sides together unless otherwise stated. Border 2 Please check our website www.rileyblakedesigns.com for any Cut 6 strips 3½” x WOF from gray dot revisions before starting this project. This pattern requires a basic knowledge of quilting technique and terminology. QUILT ASSEMBLY Refer to quilt photo for placement of strips. FABRIC REQUIREMENTS 1 yard (90 cm) black main (C3080 Black) Evening Gown Strips ¼ yard (20 cm) white main (C3080 White) Cut each strip 40½” wide. Sew strips together in the following 1/8 yard (10 cm) gray damask (C3081 Gray) order: gray petal, white flower, white dot, white main, black ¼ yard (20 cm) gray flower (C3082 Gray) stripe, white petal, and gray flower. ¼ yard (20 cm) white flower (C3082 White) 1/2 yard (40 cm) gray petal (C3083 Gray) Flower Appliqué ¼ yard (20 cm) white petal (C3083 White) Use your favorite method of appliqué. Refer to quilt photo for 5/8 yard (50 cm) gray dot (C3084 Gray) placement of large, medium, and small flowers and centers. ¼ yard (20 cm) white dot (C3084 White) ¼ yard (20 cm) black stripe (C3085 Black) Borders 1/8 yard (10 cm) clean white solid (C100-01 Clean White) Seam allowances vary so measure through the center of the 1/2 yard (40 cm) slate shade (C200-10 Slate) quilt before cutting border pieces. -

The Apparel Industry, the Retail Trade, Fashion, and Prostitution in Late 19Th Century St Louis Jennifer Marie Schulle Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2005 Fashion and fallen women: the apparel industry, the retail trade, fashion, and prostitution in late 19th century St Louis Jennifer Marie Schulle Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the United States History Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Schulle, Jennifer Marie, "Fashion and fallen women: the apparel industry, the retail trade, fashion, and prostitution in late 19th century St Louis " (2005). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 1590. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/1590 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fashion and fallen women: The apparel industry, the retail trade, fashion, and prostitution in late 19th century St. Louis by Jennifer Marie Schulle A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Textiles and Clothing Program of Study Committee: Jane Farrell-Beck, Major Professor Mary Lynn Damhorst Kathy Hickok Barbara Mack Jean Parsons Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2005 Copyright © Jennifer Marie Schulle, 2005. All rights reserved. UMI Number: 3184648 Copyright 2005 by Schulle, Jennifer Marie All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

C H R I S T Y &

C h r i s t y & C ooC Since 1773 History and Legacy by Irra K With special thanks to The Stockport library and hat museum FamilyFamily Six reigns of Royals, and Eight generations of the Christy family have forged the brand of Christys London since it’s foundation by Miller Christy in 1773, 237 years ago Following his apprenticeship to a Hatter in Edinburgh, Miller Christy created a company that would survive for generations, outliving thousands of hat makers across the former British Empire: by 1864 for example there were 53 hatting firms in Stockport alone. Throughout hundreds of years, the factory was still managed by direct descendants of the founder of the Firm ValuesValues 1919 Christys readily registered their own The Christy Collection in Stockport is appreciation testament to the influence the company of workers’ had. At its height, it employed 3000 excellent local people leaving a valuable legacy service < - During World War II, hats were not rationed in order to boost morale, and Christys supported the effort within their family-run company, effectively running it like an extended family Celebrating Victory as well as mourning the fallen at the -> end of World War I Trade MarksTrade Marks The Stockport Collection With business of Christy Papers includes a expanding to 500 page booklet detailing foreign lands, trade marks registered safeguarding around the world at the the insignia in height of the British Empire. all it’s forms These involve registering the full name, letters 'C', it’s became vital – insignia, shape, and colours as we shall see In the early days, < - several variations - > of company marks and insignia were circulated, later consolidating into the Christy crown and heraldry which is now recognised the world over Trade Marks iiiiTrade In many territories, Trade Marks were either disputed or had to be re-registered. -

How Fashion Invades the Concert Stage

MPA 0014 HOW FASHION INVADES THE CONCERT STAGE by MAUD POWELL Published in Musical America December 26, 1908 The amateur who dreams of a life of fame in music, has one of two ideas about her future work. If she has talent and personality, she fancies that her playing alone will bring the desired recognition; if artistic and fond of dress, she has visions of beautiful gowns trailing behind her on the concert platform, producing a picture of harmony and elegance. Both pictures have other sides, however. For dress plays almost as important a part in the concert as the talent itself and becomes, as the season progresses, a veritable “Old Man of the Sea.” The professional woman owes it to her public to dress fashionably, for the simple gowns of former years have passed into obscurity and with the increased importance of dress in everyday life, it has spread into all professions, until the carelessly dressed woman or one whose clothes are hopelessly old fashioned has no place in the scheme of things. The business woman receives much help from the fashion periodicals; the mother of a large family is also reached and it is possible for many persons to procure ready-made clothing, thus obviating the necessity of shopping and fitting. Valuable as these two are in the acquiring of an up-to-date wardrobe, they help the musician but little. It is absolutely essential that she have a certain style and individuality in the selection of her gowns, particularly those which must be worn before a critical audience. -

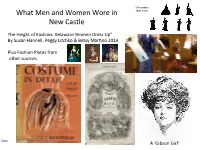

9 What People Wore.Pdf

Silhouees: What Men and Women Wore in 1860-1920 New Castle The Height of Fashion: Delaware Women Dress Up” By Susan Hannell, Peggy Litchko & Betsy Marno 2014 Plus Fashion Plates from other sources. Video A ‘Gibson Girl’ Comparison of clothing men’s clothing worn in New Castle with that worn in Victorian England In England, according to Ruth Goodman: • Hats were rarely removed in public • Waistcoats & jackets were both to be worn at all mes • Shirts not to be seen except in very informal situaons. • Pants became straight legged similar to modern ones • Underpants & undershirt or ‘union suit’ were worn Men’s and boys clothing in New Castle c1878, late Victorian mes. EVERY ONE of the people was wearing a hat, almost all were wearing a jacket and many were wearing a waistcoat (“vest”). Neckwear in portraits of men from New Castle was a cravat or ruffle unl about 1830. Coats were single or double breasted and full cut except for two seamen with youthful figures. [Cutaway jackets emphasize one’s midriff] 1759 d1798 c1804 <1811 c1830? 1785 c1805 1830 1840-1850? In 1815, Mrs. James McCullough (builder of 30 the Strand) sent her husband a package including cravats and yellow coon pants, and comments that he needs new ruffles on his shirts. (He parcularly liked “a handsomely plaited ruffle”) Nankeen trousers: (yellow coon) c1759, Anna Dorothea Finney Amstel House, 2 E 4th, by John Hesselius Lace trimmed san dress Panniers under skirt, or dome-shaped hoops, One piece; not separate bodice and skirt Bodice closed with hook & loop No stomacher Worn over a -

Replica Styles from 1795–1929

Replica Styles from 1795–1929 AVENDERS L REEN GHistoric Clothing $2.00 AVENDERS L REEN GHistoric Clothing Replica Styles from 1795–1929 Published by Lavender’s Green © 2010 Lavender’s Green January 2010 About Our Historic Clothing To our customers ... Lavender’s Green makes clothing for people who reenact the past. You will meet the public with confidence, knowing that you present an ac- curate picture of your historic era. If you volunteer at historic sites or participate in festivals, home tours, or other historic-based activities, you’ll find that the right clothing—comfortable, well made, and accu- rate in details—will add so much to the event. Use this catalog as a guide in planning your period clothing. For most time periods, we show a work dress, or “house dress.” These would have been worn for everyday by servants, shop girls, and farm wives across America. We also show at least one Sunday gown or “best” dress, which a middle-class woman would save for church, weddings, parties, photos, and special events. Throughout the catalog you will see drawings of hats and bonnets. Each one is individually designed and hand-made; please ask for a bid on a hat to wear with your new clothing. Although we do not show children’s clothing on most of these pages, we can design and make authentic clothing for your young people for any of these time periods. Generally, these prices will be 40% less than the similar adult styles. The prices given are for a semi-custom garment with a dressmaker- quality finish. -

Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018

The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Front Cover Image: Textile Detail of an Evening Dress, circa 1950s, Maker Unknown, Middlesex University Fashion Collection, London, England, F2021AB. The Middlesex University Fashion Collection comprises approximately 450 garments for women and men, textiles, accessories including hats, shoes, gloves, and more, plus hundreds of haberdashery items including buttons and trimmings, from the nineteenth century to the present day. Browse the Middlesex University Fashion Collection at https://tinyurl.com/middlesex-fashion. The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Editor–in–Chief Jennifer Daley Editor Scott Hughes Myerly Proofreader Georgina Chappell Published by The Association of Dress Historians [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org Copyright © 2018 The Association of Dress Historians ISSN 2515–0995 Online Computer Library Centre (OCLC) accession #988749854 The Journal of Dress History is the academic publication of The Association of Dress Historians through which scholars can articulate original research in a constructive, interdisciplinary, and peer reviewed environment. The Association of Dress Historians supports and promotes the advancement of public knowledge and education in the history of dress and textiles. The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) is Registered Charity #1014876 of The Charity Commission for England and Wales. The Journal of Dress History is copyrighted by the publisher, The Association of Dress Historians, while each published author within the journal holds the copyright to their individual article. The Journal of Dress History is circulated solely for educational purposes, completely free of charge, and not for sale or profit. -

Results and Discussion 83 RESULTS and DISCUSSION the Interest That Indian Women Showed in Ornamentation and Aesthetic Expression

Results and Discussion RESULTS AND DISCUSSION The interest that Indian women showed in ornamentation and aesthetic expression through their costumes has been documented well. It is pertinent to understand the messages that they conveyed through their sartorial preferences which is documented in various forms sculptures, scriptures, literature, paintings, costume archives, cinema, media –advertisements and magazines etcetera. Each community and ethnic group maintained unique characteristics, which become symbols of recognition and identification and served to establish their cultural affiliation. Central to this was the Indian woman who was the symbol of patriarchal society. She combined both the functions of being the nurturer and protector of her household and cultural ethos of the society. The woman was as important part as the man; of the Indian society, which embraced both the indoor and outdoor roles within the social- cultural paradigms of the community. The span of evolution of Indian women’s costume, especially the draped version, the sari has undergone immense changes, however to interpret the semiology of the era bygone is rather complex; as one can attempt to understand and decode the tacit meaning through the lens of current observation only. Since the people who shared the ancient set of rules or code for contextual reading that enables us to connect the signifier with the signified are not present, this will prove to be delimiting. The Indian fashion scene began receiving its due credibility and attention from 1980’s onwards and gained the industry recognition in 21st century: hence this research focuses on new millennium to understand the Indian Fashion System. -

The Morgue File 2010

the morgue file 2010 DONE BY: ASSIL DIAB 1850 1900 1850 to 1900 was known as the Victorian Era. Early 1850 bodices had a Basque opening over a che- misette, the bodice continued to be very close fitting, the waist sharp and the shoulder less slanted, during the 1850s to 1866. During the 1850s the dresses were cut without a waist seam and during the 1860s the round waist was raised to some extent. The decade of the 1870s is one of the most intricate era of women’s fashion. The style of the early 1870s relied on the renewal of the polonaise, strained on the back, gath- ered and puffed up into an detailed arrangement at the rear, above a sustaining bustle, to somewhat broaden at the wrist. The underskirt, trimmed with pleated fragments, inserting ribbon bands. An abundance of puffs, borders, rib- bons, drapes, and an outlandish mixture of fabric and colors besieged the past proposal for minimalism and looseness. women’s daywear Victorian women received their first corset at the age of 3. A typical Victorian Silhouette consisted of a two piece dress with bodice & skirt, a high neckline, armholes cut under high arm, full sleeves, small waist (17 inch waist), full skirt with petticoats and crinoline, and a floor length skirt. 1894/1896 Walking Suit the essential “tailor suit” for the active and energetic Victorian woman, The jacket and bodice are one piece, but provide the look of two separate pieces. 1859 zouave jacket Zouave jacket is a collarless, waist length braid trimmed bolero style jacket with three quarter length sleeves. -

My Father's Fortune

You loved your last book...but what are you going to read next? Using our unique guidance tools, Lovereading will help you find new books to keep you inspired and entertained. Opening Extract from… My Father’s Fortune A Life Written by Michael Frayn Published by Faber & Faber All text is copyright © of the author This Opening Extract is exclusive to Lovereading. Please print off and read at your leisure. michael frayn My Father’s Fortune A Life First published in 2010 by Faber and Faber Ltd Bloomsbury House 74–77 Great Russell Street London wc1b 3da Typeset by Faber and Faber Ltd Printed in England by CPI Mackays, Chatham All rights reserved Michael Frayn, 2010 The right of Michael Frayn to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 978–0–571–27058–3 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 Contents Homburg 1 part one 1 Smart Lad 9 2 House of Straw 19 3 Duckmore 38 4 Furniture and Fittings 55 5 Quick / Slow 74 6 Fire Resistance 91 7 A Glass of Sherry 104 part two 1 Childcare 129 2 Top to Bottom 148 3 Skylark 169 4 Chez Nous 186 5 Black Dog 203 6 Closer 222 7 Legatees 236 List of Photographs 255 Homburg The handle of my study door softly turns. I look up from my typewriter, startled. The two older children are at school, my wife’s out with the baby, the house is empty. -

Dress and Fabrics of the Mughals

Chapter IV Dress and Fabrics of the Mughals- The great Mughal emperor Akbar was not only a great ruler, an administrator and a lover of art and architecture but also a true admirer and entrepreneur of different patterns and designs of clothing. The changes and development brought by him from Ottoman origin to its Indian orientation based on the land‟s culture, custom and climatic conditions. This is apparent in the use of the fabric, the length of the dresses or their ornamentation. Since very little that is truly contemporary with the period of Babur and Humayun has survived in paintings, it is not easy to determine exactly what the various dresses look like other than what has been observed by the painters themselves. But we catch a glimpse of the foreign style of these dresses even in the paintings from Akbar‟s period which make references, as in illustrations of history or chronicles of the earlier times like the Babar-Namah or the Humayun-Namah.1 With the coming of Mughals in India we find the Iranian and Central Asian fashion in their dresses and a different concept in clothing.2 (Plate no. 1) Dress items of the Mughals: Akbar paid much attention to the establishment and working of the various karkhanas. Though articles were imported from Iran, Europe and Mongolia but effort were also made to produce various stuffs indigenously. Skilful master and workmen were invited and patronised to settle in this country to teach people and improve system of manufacture.2 Imperial workshops Karkhanas) were established in the towns of Lahore, Agra, Fatehpur Sikri and Ahmedabad.