MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 324 June 2020 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MHA Newsletter March 2015

MHA Newsletter No. 2/2015 www.mha.org.au March 2015 Merħba! A warm welcome to all the members and Submerged Lowlands settled by early humans June 2014 friends of the Maltese Historical Association. much earlier than the present mainland. June 2014 Our February lecture on Maltese politics since 1947, by English scientists tested samples of sediment recovered Dr Albert Farrugia was well attended. As I do not by archaeologists from an underwater Mesolithic Stone usually have a great interest in politics, I did not think it Age site, off the coast of the Isle of Wight. They would be very interesting. I was pleased to be proved discovered DNA from einkorn, an early form of wheat. totally wrong: it was absolutely fascinating! A summary Archeologists also found evidence of woodworking, is contained in this newsletter. Our next lecture, on 17 cooking and flint tool manufacturing. Associated March, will be given by Professor Maurice Cauchi on the material, mainly wood fragments, was dated to history of Malta through its monuments. On 21 April, between 6010 BC and 5960 BC. These indicate just before the ANZAC day weekend, Mario Bonnici will Neolithic influence 400 years earlier than proximate discuss Malta’s involvement in the First World War. European sites and 2000 years earlier than that found on mainland Britain! In this newsletter you will also find an article about how an ancient site discovered off the coast of England may The nearest area known to have been producing change how prehistory is looked at; a number of einkorn by 6000 BC is southern Italy, followed by France interesting links; an introduction to Professor Cauchi’s and eastern Spain, who were producing it by at least lecture; coming events of interest; Nino Xerri’s popular 5900 BC. -

Politiker, Präsident Von Malta Biographie Barbara, Agatha (Zabbar

Report Title - p. 1 of 6 Report Title Adami, Edward Fenech (Birkirkara, Malta 1934-) : Politiker, Präsident von Malta Biographie 1994 Edward Fenech Adami besucht China. [ChiMal3] Barbara, Agatha (Zabbar, Malta 1923-2002 Zabbar) : Politikerin, Präsidentin von Malta Biographie 1985 Agatha Barbara besucht China. [ChiMal3] Borg, Joseph = Borg, Joe (Malta 1953-) : Politiker Biographie 2000 Joseph Borg besucht China. [ChiMal3] Chen, Zhimai (1908-1978) : Chinesischer Diplomat Biographie 1944 Chen Zhimai ist Counselor der chinesischen Botschaft in Washington, D.C. [ChiMal1] 1959-1966 Chen Zhimai ist Botschafter der chinesischen Botschaft in Canberra, Australien und in New Zealand. [ChiCan1,ChiAus2] 1969 Chen Zhimai ist Botschafter im Vatikan, Italien. [ChiMal1] 1971 Chen Zhimai ist Botschafter in Valletta, Malta. [ChiMal1] Cheng, Zhiping (um 1983) : Chinesischer Diplomat Biographie 1977-1983 Cheng Zhiping ist Botschafter der chinesischen Botschaft in Valletta, Malta. [ChiMal1] Falzon, Alfred J. (um 1982) : Maltesischer Diplomat Biographie 1981-1982 Alfred J. Falzon ist Botschafter der maltesischen Botschaft in Beijing. [ChiMal2] Forace, Joseph Lennard (Valletta, Malta 1925-2005) : Diplomat Biographie 1972-1978 Joseph Lennard ist Botschafter der maltesischen Botschaft in Beijing. [ChiMal2] Gonzi, Lawrence (Valletta 1953-) : Politiker, Premierminister von Malta Biographie 1996 Lawrence Gonzi besucht China. [ChiMal3] 2000 Lawrence Gonzi besucht China. [ChiMal3] Report Title - p. 2 of 6 Guo, Jiading (um 1993) : Chinesischer Diplomat Biographie 1983-1993 -

CROWNS and CLONES in CRISIS Christ's College, Cambridge, 19

DRAFT CROWNS AND CLONES IN CRISIS The case of Malta (and Gibraltar) Christ's College, Cambridge, 19th July 2017 Henry Frendo, University of Malta Much water has passed under the bridge since Malta became an independent and sovereign state on 21st September 1964, but its essentially Westminster-style Constitution has survived with often minor amendments and changes to respond to certain circumstances as these arose. Such amendments have been largely the result of electoral quirks which needed a remedy, but some have also been political and seminal. When Malta's independence was being negotiated in the early 1960s the government of the day, the Nationalist Party led by Dr Borg Olivier, which had 26 out of the 50 parliamentary seats, sought as smooth a transition as possible from colonialism to independence. By contrast, the largest party in Opposition, led by Dominic Mintoff, wanted radical changes. Three smaller parties were opposed to Independence fearing that Malta would not survive and thrive. One bone of contention was whether Malta should remain a member of the Commonwealth or not. Another was whether Malta should be a constitutional monarchy or not. In both these cases the Borg Olivier view prevailed. Moreover the draft Constitution was approved in a referendum held in May 1964. The vision was that there would be a transition from dependence on employment with the British services, given that Malta had long been regarded and served as a strategic fortress colony in the Central Mediterranean, to a more home-grown 1 and self-sufficient outfit based on industry, tourism and agriculture. -

Censu Tabone.Pdf

• CENSU Tabone THE MAN AND HIS CENTURY Published by %ltese Studies P.O.Box 22, Valletta VLT, Malta 2000 Henry Frendo 268058 © Henry Frendo 2000 [email protected] . All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. ISBN: 99932-0-094-8 (hard-back) ISBN: 99932-0-095-6 (paper-back) Published by ~ltese Studies P.O.Box 22, Valletta VLT, Malta 2000 Set in Times New Roman by Standard Publications Ltd., St Julian's, Malta http://www.independent.com.mt Printed at Interprint Ltd., Marsa, Malta TABLE OF CONTENTS Many Faces: A FULL LIFE 9 2 First Sight: A CHILDHOOD IN GOZO 17 3 The Jesuit Formation: A BORDER AT ST ALOYSIUS 34 4 Long Trousers: STUDENT LIFE IN THE 1930s 43 5 Doctor-Soldier: A SURGEON CAPTAIN IN WARTIME 61 6 Post-Graduate Training: THE EYE DOCTOR 76 7 Marsalforn Sweetheart: LIFE WITH MARIA 87 8 Curing Trachoma: IN GOZO AND IN ASIA 94 9 A First Strike: LEADING THE DOCTORS AGAINST MINTOFF 112 10 Constituency Care: 1962 AND ALL THAT 126 11 The Party Man: ORGANISING A SECRETARIA T 144 12 Minister Tabone: JOBS, STRIKES AND SINS 164 13 In Opposition: RESISTING MINTOFF, REPLACING BORG OLIVIER 195 14 Second Thoughts: FOREIGN POLICY AND THE STALLED E.U. APPLICATION 249 15 President-Ambassador: A FATHER TO THE NATION 273 16 Two Lives: WHAT FUTURE? 297 17 The Sources: A BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE 310 18 A General Index: NAMES AND SUBJECTS 313 'Irridu naslu biex meta nghidu "ahna", ebda persuna ma thossha eskluza minn taht il-kappa ta' dik il-kelma.' Censu Tabone, Diskors fl-Okkaijoni tal-Ftuh tas-Seba' Parlament, 4 April 1992 1 Many faces A FULL LIFE CENSU Tabone is a household name in Malta. -

National Museums in Malta Romina Delia

Building National Museums in Europe 1750-2010. Conference proceedings from EuNaMus, European National Museums: Identity Politics, the Uses of the Past and the European Citizen, Bologna 28-30 April 2011. Peter Aronsson & Gabriella Elgenius (eds) EuNaMus Report No 1. Published by Linköping University Electronic Press: http://www.ep.liu.se/ecp_home/index.en.aspx?issue=064 © The Author. National Museums in Malta Romina Delia Summary In 1903, the British Governor of Malta appointed a committee with the purpose of establishing a National Museum in the capital. The first National Museum, called the Valletta Museum, was inaugurated on the 24th of May 1905. Malta gained independence from the British in 1964 and became a Republic in 1974. The urge to display the island’s history, identity and its wealth of material cultural heritage was strongly felt and from the 1970s onwards several other Museums opened their doors to the public. This paper goes through the history of National Museums in Malta, from the earliest known collections open to the public in the seventeenth century, up until today. Various personalities over the years contributed to the setting up of National Museums and these will be highlighted later on in this paper. Their enlightened curatorship contributed significantly towards the island’s search for its identity. Different landmarks in Malta’s historical timeline, especially the turbulent and confrontational political history that has marked Malta’s colonial experience, have also been highlighted. The suppression of all forms of civil government after 1811 had led to a gradual growth of two opposing political factions, involving a Nationalist and an Imperialist party. -

SAN ĠORĠ FL-ISTAMPA 1961 Sa

BAŻILIKA SAN ĠORĠ MARTRI SAN ĠORĠ FL-ISTAMPA 1961 Sa Artikli mill-Gazzetti, Rivisti, Websajts u Kotba f’Ordni Kronoloġika miġbura mill-arkivist Toni Farrugia bil-kollaborazzjoni ta' Francesco Pio Attard 0 Article by “P.M.C.” about the liturgical feast of Il-Berqa 20/04/1961 p 7 St. George. Article by Alfred Grech about changes in the Il-Berqa 08/05/1961 p 3 liturgical calender made by the Church on a number of saints, including St. George. Article by Anton C. Haber and a peom by Ġorġ Il-Berqa 12/05/1961 p 4 Pisani about St. George. Articles about the feast of St. George and about Il-Berqa 12/07/1961 p 7 trophies to be presented for winners of horse- races held on the occasion of the feast of st. George. Photo of the La Stella Band Club in 1946 Article by “Georgette” about the feast of St. George in 1901. Historical article by John Bezzina about Rabat Il-Berqa 14/07/1961 p 3-5 during the rule of Ancient Rome. “San Ġorġ fl-Arti Nisranija”: an article by Rev. J. Għawdex 01/07/1962 p 1,3 Grech Cremona. The feast of St. George. Għawdex 01/07/1962 p 4 Il-Berqa 12/07/1962 p 7 Il-Berqa 13/07/1962 p 2 Article about the titular statue of St. George. Il-Berqa 10/07/1962 p 3 Historical article by John Bezzina abour Rabat Il-Berqa 13/07/1962 p 4, 11 before and during Arab rule. Historical article by John Bezina about Rabat Il-Berqa 14/07/1962 p 7 during Ancient Greece era. -

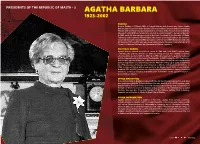

Agatha Barbara 1923-2002

PRESIDENTS OF THE REPUBLIC OF MALTA - 3 AGATHA BARBARA 1923-2002 PROFILE Born in Żabbar on 11 March 1923 to Joseph Barbara and Antonia née Agius, Agatha Barbara was the second of nine children. She received her education at the Government Primary and Grammar schools and worked as a teacher at the Flores College in Valletta. She was the first Maltese female to be elected in parliament and to become a Minister. In 1982, aged 58, she was appointed as the third President of the Republic of Malta. Following a short stint by Albert Hyzler who served as Acting President, Ms Barbara’s tenure started on 15 February 1982 and ended on 15 February 1987. She died on Monday 4 February 2002, aged 78, and was given a state funeral. Requiem mass was held at St John’s Co-Cathedral followed by internment at Żabbar Cemetery. POLITICAL CAREER Agatha Barbara started her political career in 1946 with Paul Boffa’s Labour Party, contesting the general elections of 1947 and being elected. Successfully contesting all consecutive elections with the MLP up to 1981, she retained the parliamentary seat until her appointment as President of the Republic in 1982. During the 1955 Legislature, Barbara was appointed Minister of Education and Culture, making her the first Maltese woman responsible of a ministerial portfolio. With the setting up of Cabinet following the 1972 general elections, she was reinstated as Minister of Education and Culture. In 1974, she was entrusted with a new portfolio for Works, Social Services and Culture. Between 1971 and 1981, Barbara also served as Acting Prime Minister during a few brief instances, as well as member of the Executive Committee of the Labour Party for a good number of years. -

Leadership and Women: the Space Between Us

The University of Sheffield Leadership and Women: the Space between Us. Narrating ‘my-self’ and telling the stories of senior female educational leaders in Malta. Robert Vella A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education. The University of Sheffield Faculty of Social Sciences School of Education October, 2020 ii Life is a journey and it’s about growing and changing and coming to terms with who and what you are and loving who and what you are. Kelly McGillis iii Acknowledgements Thank you for what you did; You didn’t have to do it. I’m glad someone like you Could help me to get through it. I’ll always think of you With a glad and grateful heart; You are very special; I knew it from the start! These few lines by Joanna Fuchs gather my gratitude to many persons who in some way walked with me through this journey. As the phrase goes, “no man is an island”, and surely, I would not have managed without the tremendous help and support of these mentioned below. A special thanks goes to my supervisor Emeritus Professor Pat Sikes. I am tremendous grateful for her sincere guidance, incredible patience, and her full support throughout this journey. I am very grateful for her availability and for her encouragement to explore various paths to inquire into my project. For me Pat was not just a supervisor, she was my mentor, a leader, advisor, and above all a dear friend. Mention must be made also to Professor Cathy Nutbrown and Dr David Hyatt who both offered their advice and help through these years, mostly during the study schools. -

Dati Ta' Ġieħ Għas-Soċjetà Filarmonika “Sliema”

STORJA P. ĠUŻEPP VELLA OFM • DATI TA' GIEĦ GĦAS-SOĊJETÀ FILARMONIKA "SLIEMA" ŻJARAT MINN AWTORITAJIET EKKLESJASTIĊI 4 Is-Soċjetà Filarmonika "Sliema", 1934-1936. B'tifkira ta' din iż-żjara tat-Translazzjoni , il-Banda laqgħetu minn kemm ilha mwaqqfa, kellha għadna naraw il-Kallotta tiegħu fil fix-Xatt u ġie mtella' bid-daqq tal diversi ZJarat minn persuni vetrin a tar-rigali. marċi f ' karozza mikxufa. Wara l prominenti kemm ta' Awtorità Meta fl-1948, is-Soċjetà fakkret i 1- funzjoni fil-knisja, nhar il-5 ta' Lulju, Ekklesjastika u kemm dik Ċivili. 25 sena mit-twaqqif tagħha u tal kien mistieden għal riċeviment. Il F'dan l-artiklu se nagħtu ħarsa lejn Banda, kien ġie mistieden il-Vigarju President Dr Giovanni Felice LL.D., dawk il-persuni ta' ċerta awtorità Ġenerali Mons. Isqof Emmanuele għamel diskors ta' l-okkażjoni . Wara ekklesjastika jew reliġjuża li għamlu Galea. Fis-17 ta' Ottubru 1948 bierek offrielu kallotta ġ dida u huwa ta l żjara l is-sede tas-Soċjetà. il-lapida ta' tifkira li tqieglidet fl kallotta li kellu biex tkun ta' tifkira L-ewwel persuna ekklesjastika li intrata tal-każin . 5 Waqt riċeviment li tiegħu . Mons. Perantoni għamel 9 żaret il-każin tagħna kien l-Isqof kien sar ġiet offruta kallotta ġdida u diskors ta' ringrazzjament. Ta' min Franġiskan Mons. Onorato Calcaterra huwa ħalla tiegħu bħala tifkira lis jgħid ukoll li għal dan ir-riċeviment O.F.M. li kien Vigarju Apostoliku ta' Soċjetà. 6 kien preżenti wkoll l-Arċisqof Tripli u Isqof titulari ta' Ipso. Fl-1929 Fl-24 ta' Ottubru 1948 kien ġie l Gonzi .10 Huwa wkoll ingħata kallotta Mons. -

Of the Central Region of Malta a TASTE of the HISTORY, CULTURE and ENVIRONMENT

A TASTE OF THE HISTORY, CULTURE AND ENVIRONMENT of the Central Region of Malta A TASTE OF THE HISTORY, CULTURE AND ENVIRONMENT of the Central Region of Malta Design and layout by Kite Group www.kitegroup.com.mt [email protected] George Cassar First published in Malta in 2019 Publication Copyright © Kite Group Literary Copyright © George Cassar Photography Joseph Galea Printed by Print It, Malta No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the author and the publisher. ISBN: 978-99957-50-67-1 (hardback) 978-99957-50-68-8 (paperback) THE CENTRAL REGION The Central Region is one of five administrative regions in the Maltese Islands. It includes thirteen localities – Ħ’Attard, Ħal Balzan Birkirkara, il-Gżira, l-Iklin, Ħal Lija, l-Imsida, Tal- Pietà, San Ġwann, Tas-Sliema, San Ġiljan, Santa Venera, and Ta’ Xbiex. The Region has an area of about 25km2 and a populations of about 130,574 (2017) which constitutes 28.36 percent of the population of the country. This population occupies about 8 percent of the whole area of the Maltese Islands which means that the density is of around 6,635 persons per km2. The coat-of-arms of the Central Region was granted in 2014 (L.N. 364 of 2014). The shield has a blue field signifying the Mediterranean Sea in which there are thirteen bezants or golden disks representing the thirteen municipalities forming the Region. The blazon is Azure thirteen bezants 3, 3, 3, 3 and 1, all ensigned by a mural coronet of five eschaugettes and a sally port Or. -

Monumenti U Busti Fil-Gżejjer Maltin

monumenti u busti fil-gżejjer Maltin ANTON CAMILLERI WERREJ Abbrevjazzjonijiet 24 Ħajr 25 Daħla 27 Kelmet l-awtur 29 Introduzzjoni 31 MALTA 35 Ħ’Attard 36 Monument lill-vittmi tat-Tieni Gwerra Dinjija 36 Monument lill-Papa San Ġwanni Pawlu II 37 Monument b’tifkira tal-Union Maltija tal-Infermiera u l-Qwiebel 38 Monument lin-nanniet 39 Bust lil Pierre Muscat 40 Bust lill-Mastru Karm Debono 41 Busti lir-Re Ġorġ V u r-Re Ġorġ VI 41 Bust lill-Prinċep Ġorġ – Duka ta’ Kent 42 Bust lil San Ġorġ Preca 43 Bust lil Madre Tereża 43 Busti lill-Presidenti tar-Repubblika 44 Il-Balluta 46 Bust lill-Papa San Ġwanni Pawlu II 46 Bust lill-Madonna tal-Karmnu 47 Ħal Balzan 48 Bust lil Dun Ġwann Zammit Hammet 48 Bust lil Gabriel Caruana 49 Il-Birgu 50 Monument lill-vittmi tat-Tieni Gwerra Dinjija 50 Monument tad-900 sena mit-twaqqif tal-knisja ta’ San Lawrenz parroċċa 51 Monument tal-1750 sena mill-martirju ta’ San Lawrenz 52 Monument tal-Assedju l-Kbir tal-1565 53 Monument b’tifkira ta’ Jum il-Ħelsien 54 Monument LILl-Papa San Ġwanni Pawlu II 55 Bust lil Sir Paul Boffa 56 Bust lil Nestu Laiviera 57 Bust lill-Gran Mastru Fra Nicola Cotoner 58 Bust lil Mons. Dun Ġużepp Caruana 59 7 Birkirkara 61 Monument lill-vittmi tat-Tieni Gwerra Dinjija 61 Monument tal-mitt sena mill-inkurunazzjoni tal-kwadru tal-Madonna tal-Ħerba 62 Monument lil Sir Anthony Mamo 63 Monument lill-vittmi Karkariżi tal-logħob tan-nar 64 Bust lill-Kavallier Ċensu Borg ‘Brared’ 65 Busti lill-Papa Urbanu VIII u l-Papa Piju XII 65 Busti lil Ġużeppi Briffa u Carmelo Brincat 67 Bust lil Karin Grech 68 Bust lill-Maġġur Anthony Aquilina 69 Bust lill-Mro Kavallier Ġużeppi Busuttil 70 Bust lit-Tabib Robert Farrugia Randon 71 Bust lis-Surmast Raffaele Ricci 71 Bust lis-Surmast Tommaso Galea 72 Bust lil John A. -

Past Recipients of Honours Or Awards

PAST RECIPIENTS OF MALTESE HONOURS AND AWARDS AND DATE OF CONFERMENT THE NATIONAL ORDER OF MERIT Companions of Honour 06.04.90 HE Dr Vincent Tabone KUOM 06.04.90 The Hon Eddie Fenech Adami KUOM 06.04.90 Prof Sir Anthony Mamo KUOM 06.04.90 Ms Agatha Barbara KUOM 06.04.90 The Hon Dom Mintoff KUOM 06.04.90 The Hon Karmenu Mifsud Bonnici KUOM 04.04.94 HE Dr Ugo Mifsud Bonnici KUOM 28.10.96 The Hon Dr Alfred Sant KUOM 04.04.99 HE Prof Guido de Marco KUOM 23.03.04 The Hon Lawrence Gonzi KUOM 04.04.09 HE Dr George Abela KUOM 11.03.13 The Hon Joseph Muscat KUOM 13.12.13 Mr Paul Xuereb KUOM (posthumously) 04.04.14 HE Ms Marie-Louise Coleiro Preca KUOM XIRKA ĠIEH IR-REPUBBLIKA 13.12.92 Prof Sir Anthony Mamo SĠ 13.12.95 His Grace Mgr Joseph Mercieca SĠ 13.12.05 His Lordship Nicholas J Cauchi SĠ THE NATIONAL ORDER OF MERIT Companions 13.12.92 Dr Arvid Pardo KOM 13.12.93 Dr Emanuel Bonnici KOM 13.12.93 Dr Joseph Cassar KOM 13.12.94 Chief Justice Emeritus Prof John J Cremona KOM 13.12.94 The Hon Prof Guido de Marco KOM 13.12.95 The Hon George Bonello du Puis KOM 13.12.95 Rev Prof Peter Serracino Inglott KOM 13.12.96 Mr Kalċidon Agius KOM 13.12.96 Not Dr Joseph Spiteri KOM 13.12.97 Mr Wistin Abela KOM 13.12.97 Chev Dr Jimmy Farrugia KOM 13.12.98 Chief Justice Emeritus Prof Giuseppe Mifsud Bonnici KOM 13.12.99 Dr George J Hyzler KOM 13.12.99 Rev Fr Maximilian Mizzi KOM 13.12.01 Prof John Rizzo Naudi KOM 13.12.06 Dr Giovanni Bonello KOM 13.12.06 Mr Richard Cachia Caruana KOM 13.12.07 Dr Michael Refalo KOM 13.12.08 Mr Lino Spiteri KOM 13.12.08 Mr Anton Tabone KOM 13.12.10 Prof Josef Bonnici KOM 13.12.11 Rev Prospero Grech KOM 13.12.13 Dr Michael Frendo KOM 13.12.13 Prof Edwin S Grech KOM 13.12.16 Archbishop Emeritus Paul Cremona KOM Officers 13.12.92 Dr Joseph Abela UOM 13.12.92 Dr Alexander Cachia Zammit UOM 13.12.92 Mro Carmelo Pace UOM 13.12.93 Judge Maurice Caruana Curran UOM 13.12.93 Prof Richard England UOM 13.12.94 Prof Mro.