Constitutions and Legislation in Malta 1914 - 1964

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MHA Newsletter March 2015

MHA Newsletter No. 2/2015 www.mha.org.au March 2015 Merħba! A warm welcome to all the members and Submerged Lowlands settled by early humans June 2014 friends of the Maltese Historical Association. much earlier than the present mainland. June 2014 Our February lecture on Maltese politics since 1947, by English scientists tested samples of sediment recovered Dr Albert Farrugia was well attended. As I do not by archaeologists from an underwater Mesolithic Stone usually have a great interest in politics, I did not think it Age site, off the coast of the Isle of Wight. They would be very interesting. I was pleased to be proved discovered DNA from einkorn, an early form of wheat. totally wrong: it was absolutely fascinating! A summary Archeologists also found evidence of woodworking, is contained in this newsletter. Our next lecture, on 17 cooking and flint tool manufacturing. Associated March, will be given by Professor Maurice Cauchi on the material, mainly wood fragments, was dated to history of Malta through its monuments. On 21 April, between 6010 BC and 5960 BC. These indicate just before the ANZAC day weekend, Mario Bonnici will Neolithic influence 400 years earlier than proximate discuss Malta’s involvement in the First World War. European sites and 2000 years earlier than that found on mainland Britain! In this newsletter you will also find an article about how an ancient site discovered off the coast of England may The nearest area known to have been producing change how prehistory is looked at; a number of einkorn by 6000 BC is southern Italy, followed by France interesting links; an introduction to Professor Cauchi’s and eastern Spain, who were producing it by at least lecture; coming events of interest; Nino Xerri’s popular 5900 BC. -

Politiker, Präsident Von Malta Biographie Barbara, Agatha (Zabbar

Report Title - p. 1 of 6 Report Title Adami, Edward Fenech (Birkirkara, Malta 1934-) : Politiker, Präsident von Malta Biographie 1994 Edward Fenech Adami besucht China. [ChiMal3] Barbara, Agatha (Zabbar, Malta 1923-2002 Zabbar) : Politikerin, Präsidentin von Malta Biographie 1985 Agatha Barbara besucht China. [ChiMal3] Borg, Joseph = Borg, Joe (Malta 1953-) : Politiker Biographie 2000 Joseph Borg besucht China. [ChiMal3] Chen, Zhimai (1908-1978) : Chinesischer Diplomat Biographie 1944 Chen Zhimai ist Counselor der chinesischen Botschaft in Washington, D.C. [ChiMal1] 1959-1966 Chen Zhimai ist Botschafter der chinesischen Botschaft in Canberra, Australien und in New Zealand. [ChiCan1,ChiAus2] 1969 Chen Zhimai ist Botschafter im Vatikan, Italien. [ChiMal1] 1971 Chen Zhimai ist Botschafter in Valletta, Malta. [ChiMal1] Cheng, Zhiping (um 1983) : Chinesischer Diplomat Biographie 1977-1983 Cheng Zhiping ist Botschafter der chinesischen Botschaft in Valletta, Malta. [ChiMal1] Falzon, Alfred J. (um 1982) : Maltesischer Diplomat Biographie 1981-1982 Alfred J. Falzon ist Botschafter der maltesischen Botschaft in Beijing. [ChiMal2] Forace, Joseph Lennard (Valletta, Malta 1925-2005) : Diplomat Biographie 1972-1978 Joseph Lennard ist Botschafter der maltesischen Botschaft in Beijing. [ChiMal2] Gonzi, Lawrence (Valletta 1953-) : Politiker, Premierminister von Malta Biographie 1996 Lawrence Gonzi besucht China. [ChiMal3] 2000 Lawrence Gonzi besucht China. [ChiMal3] Report Title - p. 2 of 6 Guo, Jiading (um 1993) : Chinesischer Diplomat Biographie 1983-1993 -

Codebook Indiveu – Party Preferences

Codebook InDivEU – party preferences European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies December 2020 Introduction The “InDivEU – party preferences” dataset provides data on the positions of more than 400 parties from 28 countries1 on questions of (differentiated) European integration. The dataset comprises a selection of party positions taken from two existing datasets: (1) The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File contains party positions for three rounds of European Parliament elections (2009, 2014, and 2019). Party positions were determined in an iterative process of party self-placement and expert judgement. For more information: https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/65944 (2) The Chapel Hill Expert Survey The Chapel Hill Expert Survey contains party positions for the national elections most closely corresponding the European Parliament elections of 2009, 2014, 2019. Party positions were determined by expert judgement. For more information: https://www.chesdata.eu/ Three additional party positions, related to DI-specific questions, are included in the dataset. These positions were determined by experts involved in the 2019 edition of euandi after the elections took place. The inclusion of party positions in the “InDivEU – party preferences” is limited to the following issues: - General questions about the EU - Questions about EU policy - Questions about differentiated integration - Questions about party ideology 1 This includes all 27 member states of the European Union in 2020, plus the United Kingdom. How to Cite When using the ‘InDivEU – Party Preferences’ dataset, please cite all of the following three articles: 1. Reiljan, Andres, Frederico Ferreira da Silva, Lorenzo Cicchi, Diego Garzia, Alexander H. -

Mill‑PARLAMENT

Nr 25 Diċembru 2020 December 2020 PARLAMENT TA’ MALTA mill‑PARLAMENT Perjodiku maħruġ mill‑Uffiċċju tal‑Ispeaker Periodical issued by the Office of the Speaker 1 mill-PARLAMENT - Diċembru 2020 Għotja demm... servizz soċjali mill-poplu għall-poplu Inħeġġuk biex nhar il-Ħamis, 6 ta’ Mejju 2021 bejn it-8:30am u s-1:00pm tiġi quddiem il-bini tal-Parlament biex tagħmel donazzjoni ta’ demm. Tinsiex iġġib miegħek il-karta tal-identità. Minħabba l-imxija tal-COVID-19, qed jittieħdu l-miżuri kollha meħtieġa biex tkun protett inti u l-professjonisti li se jkunu qed jassistuk. Jekk ħadt it-tilqima kontra l-COVID-19 ħalli 7 ijiem jgħaddu qabel tersaq biex tagħti d-demm. Din l-attività qed tittella’ miċ-Ċentru tal-Għoti tad-Demm b’kollaborazzjoni mas- Servizz Parlamentari u d-Dipartiment tas-Sigurtà Soċjali. Ħarġa Nru 25/Issue No. 25 3 Daħla Diċembru 2020/December 2020 Foreword 4 Attivitajiet tal-Parlament Parliamentary Activities Ippubblikat mill‑Uffiċċju tal‑Ispeaker Published by the Office of the Speaker 12 Il-Kumitat Permanenti Għall-Affarijiet ta’ Għawdex Bord Editorjali The Standing Committee on Gozo Affairs Editorial Board 14 Attivitajiet Internazzjonali Ray Scicluna International Activities Josanne Paris 16 Il-Kuxjenza u l-Membri Parlamentari Maltin Ancel Farrugia Migneco Conscience and the Maltese Members of Parliament Eleanor Scerri Eric Frendo 32 L-Elezzjonijiet F’Malta ta’ qabel l-Indipendenza 1836-1962 Elections in Pre-Independence Malta 1836-1962 Indirizz Postali Postal Address House of Representatives Freedom Square Valletta VLT 1115 -

Directorate for Quality and Standards in Education

DEPARTMENT FOR CURRICULUM, RESEARCH, INNOVATION AND LIFELONG LEARNING Directorate for Learning and Assessment Programmes Educational Assessment Unit Annual Examinations for Secondary Schools 2018 YEAR 10 HISTORY (OPTION) TIME: 1h 30min Name: _____________________________________ Class: _______________ N.B. Teachers are to add the marks obtained by the students in their fieldwork study (20 marks) done during the scholastic year at the National Archives as a formative assessment exercise so that the examination paper will add up to 100 marks. SECTION A MALTESE HISTORY 1. Look carefully at the sources and then answer the questions. Source A Source B 1.1 The person in Source B is (Sigismondo Savona, Fortunato Mizzi, Paolo Pullicino). (1) 1.2 Savona was the leader of the Reform Party. Explain, in brief, the objectives of this party. _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________ (3) 1.3.1 Who was the Royal Commissioner who proposed more use of the English language in Malta? ____________________________________________________________ (1) 1.3.2 Give two suggestions put forward by this Commissioner to this effect. _______________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________ (2) 1.4 What was the party headed by Fortunato Mizzi called? ____________________________________________________________ (1) History (Option) – Year 10 – 2018 Page 1 of -

Politics, Religion and Education in Nineteenth Century Malta

Vol:1 No.1 2003 96-118 www.educ.um.edu.mt/jmer Politics, Religion and Education in Nineteenth Century Malta George Cassar [email protected] George Cassar holds the post of lecturer with the University of Malta. He is Area Co- ordinator for the Humanities at the Junior College where he is also Subject Co-ordinator in- charge of the Department of Sociology. He holds degrees from the University of Malta, obtaining his Ph.D. with a thesis entitled Prelude to the Emergence of an Organised Teaching Corps. Dr. Cassar is author of a number of articles and chapters, including ‘A glimpse at private education in Malta 1800-1919’ (Melita Historica, The Malta Historical Society, 2000), ‘Glimpses from a people’s heritage’ (Annual Report and Financial Statement 2000, First International Merchant Bank Ltd., 2001) and ‘A village school in Malta: Mosta Primary School 1840-1940’ (Yesterday’s Schools: Readings in Maltese Educational History, PEG, 2001). Cassar also published a number of books, namely, Il-Mużew Marittimu Il-Birgu - Żjara edukattiva għall-iskejjel (co-author, 1997); Għaxar Fuljetti Simulati għall-użu fit- tagħlim ta’ l-Istorja (1999); Aspetti mill-Istorja ta’ Malta fi Żmien l-ingliżi: Ktieb ta’ Riżorsi (2000) (all Għaqda ta’ l-Għalliema ta’ l-Istorja publications); Ġrajja ta’ Skola: L-Iskola Primarja tal-Mosta fis-Sekli Dsatax u Għoxrin (1999) and Kun Af il-Mosta Aħjar: Ġabra ta’ Tagħlim u Taħriġ (2000) (both Mosta Local Council publications). He is also researcher and compiler of the website of the Mosta Local Council launched in 2001. Cassar is editor of the journal Sacra Militia published by the Sacra Militia Foundation and member on The Victoria Lines Action Committee in charge of the educational aspects. -

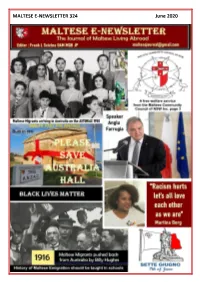

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 324 June 2020 1

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 324 June 2020 1 MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 324 June 2020 The Black Menace - When the Maltese Migrants were pushed back from Australia by Billy Hughes In 1916, Malta was a poor island, heavily caught up in WWI. It was “the nurse of the Mediterranean”, taking care of 80,000 wounded soldiers, a lot of them Australian. They were shipped in from Gallipoli and other European fronts, where Maltese men were fighting on the side of the British Empire themselves. For a small place, with only a little over 210,000 inhabitants, Malta went above and beyond, and many Australian returned soldiers were grateful. But that didn’t help the Maltese in 1916. When the Gange arrived in WA, Australia was in the grip of a referendum on conscription. Labor Prime Minister Billy Hughes, whose enthusiasm for the war had earned him the moniker “the little digger”, had become worried when the zeal to enlist had dropped off after alarming news of tens of thousands of deaths had been published. His solution was to try and see if he could force men to join the military, but for that he needed the permission of the Australian people. On the 28th of October 1916, there was to be a referendum that asked if they were okay with that. In the lead-up, the country had been split down the middle. Scared of conscription were the unions, who feared that with their members away at the front, their jobs would be taken over by women, or even worse, coloured people. -

Archbishop Michael Gonzi, Dom Mintoff, and the End of Empire in Malta

1 PRIESTS AND POLITICIANS: ARCHBISHOP MICHAEL GONZI, DOM MINTOFF, AND THE END OF EMPIRE IN MALTA SIMON C. SMITH University of Hull The political contest in Malta at the end of empire involved not merely the British colonial authorities and emerging nationalists, but also the powerful Catholic Church. Under Archbishop Gonzi’s leadership, the Church took an overtly political stance over the leading issues of the day including integration with the United Kingdom, the declaration of an emergency in 1958, and Malta’s progress towards independence. Invariably, Gonzi and the Church found themselves at loggerheads with the Dom Mintoff and his Malta Labour Party. Despite his uncompromising image, Gonzi in fact demonstrated a flexible turn of mind, not least on the central issue of Maltese independence. Rather than seeking to stand in the way of Malta’s move towards constitutional separation from Britain, the Archbishop set about co-operating with the Nationalist Party of Giorgio Borg Olivier in the interests of securing the position of the Church within an independent Malta. For their part, the British came to accept by the early 1960s the desirability of Maltese self-determination and did not try to use the Church to impede progress towards independence. In the short-term, Gonzi succeeded in protecting the Church during the period of decolonization, but in the longer-term the papacy’s softening of its line on socialism, coupled with the return to power of Mintoff in 1971, saw a sharp decline in the fortunes of the Church and Archbishop Gonzi. Although less overt than the Orthodox Church in Cyprus, the power and influence of the Catholic Church in Malta was an inescapable factor in Maltese life at the end of empire. -

Information Guide Euroscepticism

Information Guide Euroscepticism A guide to information sources on Euroscepticism, with hyperlinks to further sources of information within European Sources Online and on external websites Contents Introduction .................................................................................................. 2 Brief Historical Overview................................................................................. 2 Euro Crisis 2008 ............................................................................................ 3 European Elections 2014 ................................................................................ 5 Euroscepticism in Europe ................................................................................ 8 Eurosceptic organisations ......................................................................... 10 Eurosceptic thinktanks ............................................................................. 10 Transnational Eurosceptic parties and political groups .................................. 11 Eurocritical media ................................................................................... 12 EU Reaction ................................................................................................. 13 Information sources in the ESO database ........................................................ 14 Further information sources on the internet ..................................................... 14 Copyright © 2016 Cardiff EDC. All rights reserved. 1 Cardiff EDC is part of the University Library -

Maltese Immigrants in Detroit and Toronto, 1919-1960

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Britishers in Two Worlds: Maltese Immigrants in Detroit and Toronto, 1919-1960 Marc Anthony Sanko Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Sanko, Marc Anthony, "Britishers in Two Worlds: Maltese Immigrants in Detroit and Toronto, 1919-1960" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6565. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6565 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Britishers in Two Worlds: Maltese Immigrants in Detroit and Toronto, 1919-1960 Marc Anthony Sanko Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Kenneth Fones-Wolf, Ph.D., Chair James Siekmeier, Ph.D. Joseph Hodge, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Mary Durfee, Ph.D. Department of History Morgantown, West Virginia 2018 Keywords: Immigration History, U.S. -

IT-TLETTAX-IL LEĠIŻLATURA P.L. 4462 Raymond Scicluna Skrivan Tal-Kamra

IT-TLETTAX-IL LEĠIŻLATURA P.L. 4462 Dokument imqiegħed fuq il-Mejda tal-Kamra tad-Deputati fis-Seduta Numru 299 tas-17 ta’ Frar 2020 mill-Ministru fl-Uffiċċju tal-Prim Ministru, f’isem il-Ministru għall-Wirt Nazzjonali, l-Arti u Gvern Lokali. ___________________________ Raymond Scicluna Skrivan tal-Kamra BERĠA TA' KASTILJA - INVENTARJU TAL-OPRI TAL-ARTI 12717. L-ONOR. JASON AZZOPARDI staqsa lill-Ministru għall-Wirt Nazzjonali, l-Arti u l-Gvern Lokali: Jista' l-Ministru jwieġeb il-mistoqsija parlamentari 8597 u jgħid jekk hemmx u jekk hemm, jista’ jqiegħed fuq il-Mejda tal-Kamra l-Inventarju tal-Opri tal-Arti li hemm fil- Berġa ta’ Kastilja? Jista’ jgħid liema minnhom huma proprjetà tal-privat (fejn hu l-każ) u liema le? 29/01/2020 ONOR. JOSÈ HERRERA: Ninforma lill-Onor. Interpellant li l-ebda Opra tal-Arti li tagħmel parti mill-Kollezjoni Nazzjonali ġewwa l-Berġa ta’ Kastilja m’hi proprjetà tal-privat. għaldaqstant qed inpoġġi fuq il-Mejda tal-Kamra l-Inventarju tal-Opri tal-Arti kif mitlub mill- Onor. Interpellant. Seduta 299 17/02/2020 PQ 12717 -Tabella Berga ta' Kastilja - lnventarju tai-Opri tai-Arti INVENTORY LIST AT PM'S SEC Title Medium Painting- Madonna & Child with young StJohn The Baptist Painting- Portraits of Jean Du Hamel Painting- Rene Jacob De Tigne Textiles- banners with various coats-of-arms of Grandmasters Sculpture- Smiling Girl (Sciortino) Sculpture- Fondeur Figure of a lady (bronze statue) Painting- Dr. Lawrence Gonzi PM Painting- Francesco Buhagiar (Prime Minister 1923-1924) Painting- Sir Paul Boffa (Prime Minister 1947-1950) Painting- Joseph Howard (Prime Minister 1921-1923) Painting- Sir Ugo Mifsud (Prime Minister 1924-1927, 1932-1933) Painting- Karmenu Mifsud Bonnici (Prime Minister 1984-1987) Painting- Dom Mintoff (Prime Minister 1965-1958, 1971-1984) Painting- Lord Gerald Strickland (Prime Minister 1927-1932) Painting- Dr. -

Juridical Interest in Constitutional Proceedings

Għ.S.L Online Law Journal 2017 JURIDICAL INTEREST IN CONSTITUTIONAL PROCEEDINGS Tonio Borg1 In Maltese procedural law, the juridical interest notion is engrained in our legal system, at least in civil law. In our system, to initiate proceedings and open a case before a court of law, plaintiff or applicant must prove juridical interest which is personal in the subject matter of the litigation. He cannot start proceedings in order to obtain an opinion, or for mere personal satisfaction. There must be a tangible benefit to him in consequence of a breached legal right . In Emilio Persiano vs. Commissioner of Police2 the First Hall of the Civil Court explained the doctrine as follows: For several years our Courts have defined the elements constituting the interest of plaintiff in a cause as being three: that is to say , the interest must be juridical, it must be direct and personal, and also actual. By the first element one understands that the interest must at least contain the seed of the existence of a right and the need to safeguard such right from any attempts by others to infringe it; This interest need not be in money or economic in nature (see for instance Court of Appeal, Falzon Sant Manduca vs. Weale, decided on 9th January 1959 Kollezz. Vol. XLIII.i.1); apart from these elements, it has been stated that for a person to have interest in opening a case, that interest or better still the motive of the claim has to be concrete and existing vis a vis the person against whom the claim is made( see for instance a judgment of this court (First Hall JSP) delivered on 13th march 1992 in the case Francis Tonna vs.