Nerik Mizzi: the Formative Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mill‑PARLAMENT

Nr 25 Diċembru 2020 December 2020 PARLAMENT TA’ MALTA mill‑PARLAMENT Perjodiku maħruġ mill‑Uffiċċju tal‑Ispeaker Periodical issued by the Office of the Speaker 1 mill-PARLAMENT - Diċembru 2020 Għotja demm... servizz soċjali mill-poplu għall-poplu Inħeġġuk biex nhar il-Ħamis, 6 ta’ Mejju 2021 bejn it-8:30am u s-1:00pm tiġi quddiem il-bini tal-Parlament biex tagħmel donazzjoni ta’ demm. Tinsiex iġġib miegħek il-karta tal-identità. Minħabba l-imxija tal-COVID-19, qed jittieħdu l-miżuri kollha meħtieġa biex tkun protett inti u l-professjonisti li se jkunu qed jassistuk. Jekk ħadt it-tilqima kontra l-COVID-19 ħalli 7 ijiem jgħaddu qabel tersaq biex tagħti d-demm. Din l-attività qed tittella’ miċ-Ċentru tal-Għoti tad-Demm b’kollaborazzjoni mas- Servizz Parlamentari u d-Dipartiment tas-Sigurtà Soċjali. Ħarġa Nru 25/Issue No. 25 3 Daħla Diċembru 2020/December 2020 Foreword 4 Attivitajiet tal-Parlament Parliamentary Activities Ippubblikat mill‑Uffiċċju tal‑Ispeaker Published by the Office of the Speaker 12 Il-Kumitat Permanenti Għall-Affarijiet ta’ Għawdex Bord Editorjali The Standing Committee on Gozo Affairs Editorial Board 14 Attivitajiet Internazzjonali Ray Scicluna International Activities Josanne Paris 16 Il-Kuxjenza u l-Membri Parlamentari Maltin Ancel Farrugia Migneco Conscience and the Maltese Members of Parliament Eleanor Scerri Eric Frendo 32 L-Elezzjonijiet F’Malta ta’ qabel l-Indipendenza 1836-1962 Elections in Pre-Independence Malta 1836-1962 Indirizz Postali Postal Address House of Representatives Freedom Square Valletta VLT 1115 -

Directorate for Quality and Standards in Education

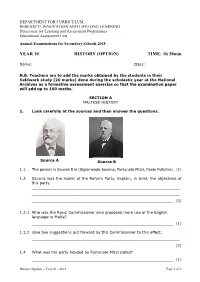

DEPARTMENT FOR CURRICULUM, RESEARCH, INNOVATION AND LIFELONG LEARNING Directorate for Learning and Assessment Programmes Educational Assessment Unit Annual Examinations for Secondary Schools 2018 YEAR 10 HISTORY (OPTION) TIME: 1h 30min Name: _____________________________________ Class: _______________ N.B. Teachers are to add the marks obtained by the students in their fieldwork study (20 marks) done during the scholastic year at the National Archives as a formative assessment exercise so that the examination paper will add up to 100 marks. SECTION A MALTESE HISTORY 1. Look carefully at the sources and then answer the questions. Source A Source B 1.1 The person in Source B is (Sigismondo Savona, Fortunato Mizzi, Paolo Pullicino). (1) 1.2 Savona was the leader of the Reform Party. Explain, in brief, the objectives of this party. _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________ (3) 1.3.1 Who was the Royal Commissioner who proposed more use of the English language in Malta? ____________________________________________________________ (1) 1.3.2 Give two suggestions put forward by this Commissioner to this effect. _______________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________ (2) 1.4 What was the party headed by Fortunato Mizzi called? ____________________________________________________________ (1) History (Option) – Year 10 – 2018 Page 1 of -

Politics, Religion and Education in Nineteenth Century Malta

Vol:1 No.1 2003 96-118 www.educ.um.edu.mt/jmer Politics, Religion and Education in Nineteenth Century Malta George Cassar [email protected] George Cassar holds the post of lecturer with the University of Malta. He is Area Co- ordinator for the Humanities at the Junior College where he is also Subject Co-ordinator in- charge of the Department of Sociology. He holds degrees from the University of Malta, obtaining his Ph.D. with a thesis entitled Prelude to the Emergence of an Organised Teaching Corps. Dr. Cassar is author of a number of articles and chapters, including ‘A glimpse at private education in Malta 1800-1919’ (Melita Historica, The Malta Historical Society, 2000), ‘Glimpses from a people’s heritage’ (Annual Report and Financial Statement 2000, First International Merchant Bank Ltd., 2001) and ‘A village school in Malta: Mosta Primary School 1840-1940’ (Yesterday’s Schools: Readings in Maltese Educational History, PEG, 2001). Cassar also published a number of books, namely, Il-Mużew Marittimu Il-Birgu - Żjara edukattiva għall-iskejjel (co-author, 1997); Għaxar Fuljetti Simulati għall-użu fit- tagħlim ta’ l-Istorja (1999); Aspetti mill-Istorja ta’ Malta fi Żmien l-ingliżi: Ktieb ta’ Riżorsi (2000) (all Għaqda ta’ l-Għalliema ta’ l-Istorja publications); Ġrajja ta’ Skola: L-Iskola Primarja tal-Mosta fis-Sekli Dsatax u Għoxrin (1999) and Kun Af il-Mosta Aħjar: Ġabra ta’ Tagħlim u Taħriġ (2000) (both Mosta Local Council publications). He is also researcher and compiler of the website of the Mosta Local Council launched in 2001. Cassar is editor of the journal Sacra Militia published by the Sacra Militia Foundation and member on The Victoria Lines Action Committee in charge of the educational aspects. -

Maltese Immigrants in Detroit and Toronto, 1919-1960

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Britishers in Two Worlds: Maltese Immigrants in Detroit and Toronto, 1919-1960 Marc Anthony Sanko Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Sanko, Marc Anthony, "Britishers in Two Worlds: Maltese Immigrants in Detroit and Toronto, 1919-1960" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6565. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6565 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Britishers in Two Worlds: Maltese Immigrants in Detroit and Toronto, 1919-1960 Marc Anthony Sanko Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Kenneth Fones-Wolf, Ph.D., Chair James Siekmeier, Ph.D. Joseph Hodge, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Mary Durfee, Ph.D. Department of History Morgantown, West Virginia 2018 Keywords: Immigration History, U.S. -

Parlament Ta' Malta

Nr 8 Marzu 2015 March 2015 PARLAMENT TA’ MALTA mill‑PARLAMENT Perjodiku maħruġ mill‑Uffiċċju tal‑Ispeaker Periodical issued by the Office of the Speaker mill-PARLAMENT - Marzu 2015 Kors ta’ tifi tan-nar mill-Protezzjoni Ċivili lill-istaff The staff of the Maltese Parliament during a fire tal-Parlament bi tħejjija għad-dħul fil-bini il-ġdid extinguishing course given by the Civil Protection, in tal-Parlament. preparation for the entry into Parliament’s new building. Ħarġa Nru 8/Issue No. 3 Daħla Marzu 2015/March 2015 Foreword Ippubblikat mill‑Uffiċċju tal‑Ispeaker 4 L-Onorarju tal-Membri Eletti: Għadma ta’ tilwim minn Published by the Office of the Speaker Għanqudu The Honorarium of the Elected Members: A Veritable Bone of Bord Editorjali Contention from the Womb Editorial Board Ray Scicluna Josanne Paris 8 Attivitajiet tal-Parlament Ancel Farrugia Migneco Activities in Parliament Eleanor Scerri Sarah Gauci Eric Frendo 12 Ħarsa ġenerali lejn l-iżvilupp tal-partiti politiċi f’Malta kolonjali (1800-1964) Indirizz Postali An overview of the political parties in colonial Malta (1800-1964) Postal Address House of Representatives 18 Attivitajiet Internazzjonali Republic Street International Activities Valletta VLT 1115 Malta +356 2559 6000 Qoxra: Veduta tal-bitħa tal-Palazz www.parlament.mt Cover: Bird’s eye view of the Palace courtyard [email protected] Ritratti/Photos: ISSN 2308‑538X Parlament ta’ Malta/DOI ISSN (online) 2308‑6637 2 Marzu 2015 mill-PARLAMENT - Daħla Foreword Dawn l-aħħar tliet xhur, bejn Jannar u l-aħħar ta’ Marzu These last three months, between January and the end ta’ din is-sena, kienu xhur impenjattivi ħafna għal dan of March of this year, were very demanding months il-Parlament. -

Maltese Colonial Identity: Latin Mediterranean Or British Empire?

The British Colonial Experience 1800-1964 The Impact on Maltese Society Edited by Victor Mallia-Milanes 2?79G ~reva Publications Published under the auspices of The Free University: Institute of Cultural Anthropology! Sociology of Development Amsterdam 10 HENRY FRENDO Maltese Colonial Identity: Latin Mediterranean or British Empire? Influenced by history as much as by geography, identity changes, or develops, both as a cultural phenomenon and in relation to economic factors. Behaviouristic traits, of which one may not be conscious, assume a different reality in cross-cultural interaction and with the passing of time. The Maltese identity became, and is, more pronounced than that of other Mediterranean islanders from the Balearic to the Aegean. These latter spoke varieties of Spanish and Greek in much the same way as the inhabitants of the smaller islands of Pantalleria, Lampedusa, or Elba spoke Italian dialects and were absorbed by the neighbouring larger mainlands. The inhabitants of modern Malta, however, spoke a language derived from Arabic at the same time as they practised the Roman Catholic faith and were exposed, indeed subjected, to European iDfluences for six or seven centuries, without becoming integrated with their closest terra firma, Italy.l This was largely because of Malta's strategic location between southern Europe and North Mrica. An identifiable Maltese nationality was thus moulded by history, geography, and ethnic admixture - the Arabic of the Moors, corsairs, and slaves, together with accretions from several northern and southern European races - from Normans to Aragonese. Malta then passed under the Knights of St John, the French, and much more importantly, the British. -

IT-TLETTAX-IL LEĠIŻLATURA P.L. 4462 Raymond Scicluna Skrivan Tal-Kamra

IT-TLETTAX-IL LEĠIŻLATURA P.L. 4462 Dokument imqiegħed fuq il-Mejda tal-Kamra tad-Deputati fis-Seduta Numru 299 tas-17 ta’ Frar 2020 mill-Ministru fl-Uffiċċju tal-Prim Ministru, f’isem il-Ministru għall-Wirt Nazzjonali, l-Arti u Gvern Lokali. ___________________________ Raymond Scicluna Skrivan tal-Kamra BERĠA TA' KASTILJA - INVENTARJU TAL-OPRI TAL-ARTI 12717. L-ONOR. JASON AZZOPARDI staqsa lill-Ministru għall-Wirt Nazzjonali, l-Arti u l-Gvern Lokali: Jista' l-Ministru jwieġeb il-mistoqsija parlamentari 8597 u jgħid jekk hemmx u jekk hemm, jista’ jqiegħed fuq il-Mejda tal-Kamra l-Inventarju tal-Opri tal-Arti li hemm fil- Berġa ta’ Kastilja? Jista’ jgħid liema minnhom huma proprjetà tal-privat (fejn hu l-każ) u liema le? 29/01/2020 ONOR. JOSÈ HERRERA: Ninforma lill-Onor. Interpellant li l-ebda Opra tal-Arti li tagħmel parti mill-Kollezjoni Nazzjonali ġewwa l-Berġa ta’ Kastilja m’hi proprjetà tal-privat. għaldaqstant qed inpoġġi fuq il-Mejda tal-Kamra l-Inventarju tal-Opri tal-Arti kif mitlub mill- Onor. Interpellant. Seduta 299 17/02/2020 PQ 12717 -Tabella Berga ta' Kastilja - lnventarju tai-Opri tai-Arti INVENTORY LIST AT PM'S SEC Title Medium Painting- Madonna & Child with young StJohn The Baptist Painting- Portraits of Jean Du Hamel Painting- Rene Jacob De Tigne Textiles- banners with various coats-of-arms of Grandmasters Sculpture- Smiling Girl (Sciortino) Sculpture- Fondeur Figure of a lady (bronze statue) Painting- Dr. Lawrence Gonzi PM Painting- Francesco Buhagiar (Prime Minister 1923-1924) Painting- Sir Paul Boffa (Prime Minister 1947-1950) Painting- Joseph Howard (Prime Minister 1921-1923) Painting- Sir Ugo Mifsud (Prime Minister 1924-1927, 1932-1933) Painting- Karmenu Mifsud Bonnici (Prime Minister 1984-1987) Painting- Dom Mintoff (Prime Minister 1965-1958, 1971-1984) Painting- Lord Gerald Strickland (Prime Minister 1927-1932) Painting- Dr. -

Malta Post Garibaldi.Pdf

HENRY FRENDO MALTA POST-GARIBALDI Istituto Italiano di Cultura, Valletta, 23 November 2007 GARIBALDI E IL RISORGIMENTO Bicentenario della nascita di Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807 -2007) Offprint from: MELITA HISTORICA VOL. XIV no. 4 (2007) Melita Historica, 2007 ISSN 1021-6952 Vol. XIV, no. 4: 439-445 MA~TA POST-GARIBALDI Istituto Italiano di Cultura, Valletta, 23 November 2007 GARIBALDI E IL RISORGIMENTO Bicentenario della nascita di Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807-2007) Henry Frendo Like Mazzini, a kindred spirit and mentor, Garibaldi is not just a personality: he is a symbol, a movement, an inspiration, an identity tag. In commemoration of the bicentenary of his birth, the Istituto Italiano di Cultura and the University of Malta jointly hosted a fitting conference (which I had the honour to chair and address) entitled Garibaldi e it Risorgimento. Garibaldi's contribution to Italian unification has to be seen on an international no less thl;ln a 'national' canvas, especially in Europe from the' Austrian borders . to the Eastern Mediterranean and beyond, as Professor Sergio La Salvia showed.l There were also inter.nal differences within the Risorgimento movement itself; moderates and democrats, monarchists and republicans, clericals and anticlericals, with Garibaldi falling in between two stools as he eventually 'converted', for pragmatic purposes; from republican to monarchist. There were countless variables in diplomacy and war, the onetime 'liberal' Pio Nono and the Papacy, the shifting role of France, Austria and Naples, the various states and principalities, and pmticularly Britain, a constitutional monarchy which suppOlted the movement partly for its own ends, but which was also a country whose social and political institutions - parliament, suffrage, education - were much admired by the rebels. -

A SOCIOLOGICAL STUDY of the MOVEMENT for INDEPENDENCE MALTA's BITTER STRUGGLE by TITO C

A SOCIOLOGICAL STUDY OF THE MOVEMENT FOR INDEPENDENCE MALTA'S BITTER STRUGGLE by TITO C. SAMMUT, B.A., M.A. A THESIS IN SOCIOLOGY Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved Accepted (y Dean ot tntnf^e Graclua//Graduatfee School December, 1972 r3 I 972 TABLE OF CONTENTS lntToa(k.dn^. 1 Chapter One THE LONG ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE 7 Chapter Two LEADERSHIP AND THE MALTESE CHARACTER ^^ Chapter Three BIRTH OF REBELS 47 Chapter Four THE LAST FEW BITTER MILES TO INDEPENDENCE 61 Conclusion 97 Bibliography 101 11 INTRODUCTION As far back in Maltese history as one can go, men are found eager to establish a religion which would furnish some sort of security to the nation. No records have been left about the religious practices of the very first settlers that occupied Malta; yet they left so many Neolithic monu ments behind them that one can visualize the strength and the power of these first Maltese. Celia Topp, in her Pre- Historic Malta, wrote, "You will leap the centuries and visit the world- famous Neolithic Temples of Tarxien, Mnajdra, Hagiar-Qim. Still in the Same period you will descend the spiral stairway of the wonderful under ground temple and necropolis, the Hypogeum. All the time you have been wandering in the twilight realm of prehistory, where you can let your fancy freely roam,..Close your eyes in these temples and imagine you are praying to the gods they worshipped, those gods might vouchsafe you a vision that would be infinitely superior to all guesses,"! When the Apostle Paul was shipwrecked on the shores of Malta, he found a religious people, but a people whose mind was pregnant with religious superstitions. -

History for Year 10

HISTORY FOR YEAR 10 English Version History Department, Curriculum Centre Annexe 2021 Edition List of Units Unit 1. LO 5. Socio-Economic Development in Malta: 1800-2004 p. 1 Unit 2. LO 9. Politics in Malta under the British p. 15 Unit 3. LO 11. Malta’s built heritage under the British p. 22 Unit 4. LO 12. Malta and Europe under the British p. 28 Forward This booklet is intended to provide English-speaking students with the necessary historical background of the topics covered in the New History General Curriculum for Year 10 which will come into effect in September 2021. Raymond Spiteri, Education Officer, History For the History Department within the Directorate of Learning and Assessment Programmes (MEDE) September 2020 LO 5. Socio-Economic Development in Malta: 1800-2004 Growth of towns and villages Learning Outcome 5 I can investigate and discuss political, social and economic changes, landmarks, developments and contrasts in Maltese society from 1800 to 2004. Assessment Criteria Assessment Criteria (MQF 1) Assessment Criteria (MQF 2) Assessment Criteria (MQF 3) 5.3f Discuss reasons for changes 5.2f Describe changes in Malta’s and developments in Maltese settlement patterns during the settlement patterns from the early British period. British period to the present-day. The increase in population was reflected in changes in the number, size and form of the towns and the villages. In 1800 the settlement pattern consisted of two basic structures: the large, compact villages in the countryside and the group of towns and suburbs founded during the Order around the Grand Harbour. -

Migrated Archives): Cyprus

Colonial administration records (migrated archives): Cyprus Formerly part of the Ottoman Empire, Cyprus was handed over to Britain Constitutional and government by Turkey for administrative purposes in 1878, though not formally ceded. Responsibility for Cypriot affairs was transferred from the Foreign Office to the FCO 141/4204-4205: Lord Radcliffe’s Constitutional proposals 1956-58 Colonial Office on 6 December 1880. Following the outbreak of the First World War, and the decision of the Ottoman Empire to join the war on the side of the FCO 141/4245: negotiations relating to the Treaty of Establishment of the Central Powers, Cyprus was annexed to the British crown. The annexation was Republic of Cyprus, 16 August 1959 recognised by both Turkey and Greece under the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne and in 1925 Cyprus became a British Crown Colony. Cyprus became an independent FCO 141/4209: partition proposals 1957-59 republic on 16 August 1960 and a member of the Commonwealth on 13 March 1961. Policing, intelligence, security and emergency This tranche of files relating to the administration of Cyprus covers the years FCO 141/2451: censorship of newspapers 1931-35 1931 – 1960, but the bulk of the material dates from the 1950s. Topics covered include politics in the later 1950s, detention law and the establishment of FCO 141/2447: arson attack on Government House, including legal action British sovereign base areas. Below is a selection of files grouped according against perpetrator 1931-32 to some major themes to assist research. Please note that this guide is not a full list of the files included in this release and should therefore be used in FCO 141/2449: civil disturbances; correspondence with Leontios, Bishop of conjunction with the full list as it appears in Discovery, our online catalogue. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses An investigation into the evolution of Maltese geopolitical thought: its heritage, renaissance and rejuvenation Baggett, Ian Robert How to cite: Baggett, Ian Robert (1998) An investigation into the evolution of Maltese geopolitical thought: its heritage, renaissance and rejuvenation, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4739/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE EVOLUTION OF MALTESE GEOPOLITICAL THOUGHT: Its heritage, renaissance and rejuvenation ? The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without the written consent of the author and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Jan Robert Baggett Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Geography University of Durham December