Malta Post Garibaldi.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directorate for Quality and Standards in Education

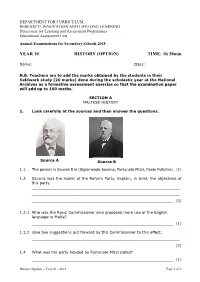

DEPARTMENT FOR CURRICULUM, RESEARCH, INNOVATION AND LIFELONG LEARNING Directorate for Learning and Assessment Programmes Educational Assessment Unit Annual Examinations for Secondary Schools 2018 YEAR 10 HISTORY (OPTION) TIME: 1h 30min Name: _____________________________________ Class: _______________ N.B. Teachers are to add the marks obtained by the students in their fieldwork study (20 marks) done during the scholastic year at the National Archives as a formative assessment exercise so that the examination paper will add up to 100 marks. SECTION A MALTESE HISTORY 1. Look carefully at the sources and then answer the questions. Source A Source B 1.1 The person in Source B is (Sigismondo Savona, Fortunato Mizzi, Paolo Pullicino). (1) 1.2 Savona was the leader of the Reform Party. Explain, in brief, the objectives of this party. _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________ (3) 1.3.1 Who was the Royal Commissioner who proposed more use of the English language in Malta? ____________________________________________________________ (1) 1.3.2 Give two suggestions put forward by this Commissioner to this effect. _______________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________ (2) 1.4 What was the party headed by Fortunato Mizzi called? ____________________________________________________________ (1) History (Option) – Year 10 – 2018 Page 1 of -

Politics, Religion and Education in Nineteenth Century Malta

Vol:1 No.1 2003 96-118 www.educ.um.edu.mt/jmer Politics, Religion and Education in Nineteenth Century Malta George Cassar [email protected] George Cassar holds the post of lecturer with the University of Malta. He is Area Co- ordinator for the Humanities at the Junior College where he is also Subject Co-ordinator in- charge of the Department of Sociology. He holds degrees from the University of Malta, obtaining his Ph.D. with a thesis entitled Prelude to the Emergence of an Organised Teaching Corps. Dr. Cassar is author of a number of articles and chapters, including ‘A glimpse at private education in Malta 1800-1919’ (Melita Historica, The Malta Historical Society, 2000), ‘Glimpses from a people’s heritage’ (Annual Report and Financial Statement 2000, First International Merchant Bank Ltd., 2001) and ‘A village school in Malta: Mosta Primary School 1840-1940’ (Yesterday’s Schools: Readings in Maltese Educational History, PEG, 2001). Cassar also published a number of books, namely, Il-Mużew Marittimu Il-Birgu - Żjara edukattiva għall-iskejjel (co-author, 1997); Għaxar Fuljetti Simulati għall-użu fit- tagħlim ta’ l-Istorja (1999); Aspetti mill-Istorja ta’ Malta fi Żmien l-ingliżi: Ktieb ta’ Riżorsi (2000) (all Għaqda ta’ l-Għalliema ta’ l-Istorja publications); Ġrajja ta’ Skola: L-Iskola Primarja tal-Mosta fis-Sekli Dsatax u Għoxrin (1999) and Kun Af il-Mosta Aħjar: Ġabra ta’ Tagħlim u Taħriġ (2000) (both Mosta Local Council publications). He is also researcher and compiler of the website of the Mosta Local Council launched in 2001. Cassar is editor of the journal Sacra Militia published by the Sacra Militia Foundation and member on The Victoria Lines Action Committee in charge of the educational aspects. -

Maltese Colonial Identity: Latin Mediterranean Or British Empire?

The British Colonial Experience 1800-1964 The Impact on Maltese Society Edited by Victor Mallia-Milanes 2?79G ~reva Publications Published under the auspices of The Free University: Institute of Cultural Anthropology! Sociology of Development Amsterdam 10 HENRY FRENDO Maltese Colonial Identity: Latin Mediterranean or British Empire? Influenced by history as much as by geography, identity changes, or develops, both as a cultural phenomenon and in relation to economic factors. Behaviouristic traits, of which one may not be conscious, assume a different reality in cross-cultural interaction and with the passing of time. The Maltese identity became, and is, more pronounced than that of other Mediterranean islanders from the Balearic to the Aegean. These latter spoke varieties of Spanish and Greek in much the same way as the inhabitants of the smaller islands of Pantalleria, Lampedusa, or Elba spoke Italian dialects and were absorbed by the neighbouring larger mainlands. The inhabitants of modern Malta, however, spoke a language derived from Arabic at the same time as they practised the Roman Catholic faith and were exposed, indeed subjected, to European iDfluences for six or seven centuries, without becoming integrated with their closest terra firma, Italy.l This was largely because of Malta's strategic location between southern Europe and North Mrica. An identifiable Maltese nationality was thus moulded by history, geography, and ethnic admixture - the Arabic of the Moors, corsairs, and slaves, together with accretions from several northern and southern European races - from Normans to Aragonese. Malta then passed under the Knights of St John, the French, and much more importantly, the British. -

Friendship, Crisis and Estrangement: U.S.-Italian Relations, 1871-1920

FRIENDSHIP, CRISIS AND ESTRANGEMENT: U.S.-ITALIAN RELATIONS, 1871-1920 A Ph.D. Dissertation by Bahar Gürsel Department of History Bilkent University Ankara March 2007 To Mine & Sinan FRIENDSHIP, CRISIS AND ESTRANGEMENT: U.S.-ITALIAN RELATIONS, 1871-1920 The Institute of Economics and Social Sciences of Bilkent University by BAHAR GÜRSEL In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA March 2007 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. --------------------------------- Asst. Prof. Dr. Timothy M. Roberts Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. --------------------------------- Asst. Prof. Dr. Nur Bilge Criss Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. --------------------------------- Asst. Prof. Dr. Edward P. Kohn Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. --------------------------------- Asst. Prof. Dr. Oktay Özel Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. -

Nerik Mizzi: the Formative Years

NERIK MIZZI: THE FORMATIVE YEARS Andrew P. Vella Memorial Lecture, MUHS, Aula Magna, Valletta, 6th February 2009 Henry Frendo Enrico Mizzi, who died in 1950 in harness as prime minister of Malta, was popularly knoyvn as 'Nerik'. Between the wars, as the Anglicization drive drew strength in proportion to the loss of constitutional freedoms, pro British newspapers such as Bartolo's Chronicle and Strickland's Times would refer to him teasingly as 'Henry', a name he did not recognize. In fact, at home, his mother, a Fogliero de Luna from Marseilles, called him 'Henri'. Malta's all-encompassing and apparently never-ending language question seemed to be personified in his very name. I remember when in the early 1970s the late Geraldu Azzopardi (a veteran dockyard worker and Labour militant with a literary inclination) had become interested in my pioneering writings on the Sette Giugno and Manwel Oimech, he had assumed that having been named after Mizzi, I could be nothing but a dyed-in-the-wool Nationalist. No doubt he had been named after Sir Gerald Strickland. But I had been simply named after my paternal grand father Enrico, better known as 'Hennie', who was indeed a friend of Mizzi. The photograph of the young Mizzi we are projecting here belonged to him, with a dedication across the bottom part of it "aWamico Enrico". In fact, however, Hennie had contested his first and only general election in 1921 as a Labour Party candidate, becoming its assistant secretary for some years and signing the MLP executive minutes in the absence of Ganni Bencini, a former Panzavecchian who had become one of the Camera del Lavoro's founders and its first general secretary until the early 1930s. -

1-2 Garibaldi.Indd

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Unitus DSpace Garibaldi, i Garibaldi, i garibaldini e l’emigrazione Emilio Franzina e Matteo Sanfilippo1 1. Esilio ed emigrazione Nei primi capitoli di Nostromo, pubblicato nel 1904, Joseph Conrad descrive non soltanto l’ambiente geografico, ma anche i personaggi principali. Tra questi si distingue l’anziano albergatore Giorgio Viola, che determinerà l’esito finale, ma che a noi qui interessa perché è un italiano, anzi un ligure, emigrato in Sud America. Di Viola Conrad sottolinea più volte che è stato un garibaldino e agli inizi del terzo capitolo specifica che era “often called simply the ‘Garibaldino’ (as Mohammendans are called after their prophet)”. Poche righe più sotto spiega il parallelo: “The old re- publican did not believe in saints, or in prayers, or in what he called ‘priests’ religion”. Liberty and Garibaldi were his divinities”2. Nel corso del romanzo l’autore riassume la biografia di Viola. Questi è stato in America Latina durante la sua gioventù, ma ha abbandonato la nave commerciale, sulla quale navigava, per seguire Garibaldi a Montevideo. In seguito è rimasto con il generale sino ai fatti dell’Aspromonte, quan- do gli è apparso evidente il tradimento del re italiano e dei suoi ministri. Viola è in- fatti convinto che questi ultimi abbiano rubato l’Italia “from us soldiers of liberty”3. Nella nota introduttiva anteposta all’edizione del 1917, Conrad spiega che ha scelto alcuni italiani come protagonisti del suo romanzo sull’America Latina, perché essi erano presenti in tutto il subcontinente. -

History for Year 10

HISTORY FOR YEAR 10 English Version History Department, Curriculum Centre Annexe 2021 Edition List of Units Unit 1. LO 5. Socio-Economic Development in Malta: 1800-2004 p. 1 Unit 2. LO 9. Politics in Malta under the British p. 15 Unit 3. LO 11. Malta’s built heritage under the British p. 22 Unit 4. LO 12. Malta and Europe under the British p. 28 Forward This booklet is intended to provide English-speaking students with the necessary historical background of the topics covered in the New History General Curriculum for Year 10 which will come into effect in September 2021. Raymond Spiteri, Education Officer, History For the History Department within the Directorate of Learning and Assessment Programmes (MEDE) September 2020 LO 5. Socio-Economic Development in Malta: 1800-2004 Growth of towns and villages Learning Outcome 5 I can investigate and discuss political, social and economic changes, landmarks, developments and contrasts in Maltese society from 1800 to 2004. Assessment Criteria Assessment Criteria (MQF 1) Assessment Criteria (MQF 2) Assessment Criteria (MQF 3) 5.3f Discuss reasons for changes 5.2f Describe changes in Malta’s and developments in Maltese settlement patterns during the settlement patterns from the early British period. British period to the present-day. The increase in population was reflected in changes in the number, size and form of the towns and the villages. In 1800 the settlement pattern consisted of two basic structures: the large, compact villages in the countryside and the group of towns and suburbs founded during the Order around the Grand Harbour. -

The Dante Alighieri Society and the British Council Contesting the Mediterranean in the 1930S Van Kessel, T.M.C

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Cultural promotion and imperialism: the Dante Alighieri Society and the British Council contesting the Mediterranean in the 1930s van Kessel, T.M.C. Publication date 2011 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): van Kessel, T. M. C. (2011). Cultural promotion and imperialism: the Dante Alighieri Society and the British Council contesting the Mediterranean in the 1930s. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:24 Sep 2021 CHAPTER 4 THE BATTLE FOR CULTURAL HEGEMONY IN MALTA In its protectorate Malta, the British government from the early 1920s onwards tried to suppress the Italian nationalists who were asking for greater independence. The embodiment of this hard-line policy was the leader of the pro-British Constitutional Party and Prime Minister in Malta between 1927 and 1932, Lord Gerald Strickland. -

He English Nation

HE ENGLISH NATION E PEOPLE OF MALTA ->*<- July 1901. THE PEOPLE OF MALTA c . The Maltese find themselves since a century under British Rule and during all this period have always given constant proofs of loyalty. It was not through conquest that they have formed part of the British Empire, but at their own free will they applied for the Pro~ectorate. Towardi:3 the end of the XVII century Napoleon Bonaparte had taken the Island from the Knights of "St. John; but within a very short time after this event, the Maltese, who could not adapt themselves to the conquest, rose in arms against the Republic, unaided, without seeking anyone's help; and after that they had, alone. already fought for a long time, they were provided \vith arms and ammunitions fl'Om England and from other powers. They were fighting for their freedom and their own indipendence and they were winning. General Graham recognizes all this in his proclamation of the • 19th June 1801 where he says: "Brave Maltese !.... given in prey of invaders .... an eternal slavery seemed to be your inevitable destiny .... you broke in pieces your chains .... your courage confined your enemy behind the ramparts .... To arms, then, 0 Maltese, for GOD and your COUNTRy!.... Success will recom pense your labour, and you will return instantly into the bosom of your families, proud, justly proud, of HAVING SAVED YOUR COUNTRY! My Master sovereign of a people free and generous, sent me to support you. " -God gave victory to the Maltese. But the Treaty of Amiens decided to give tbe Maltese back to the Govern ment of the Order, much against their will and to th.eir great disappointment. -

Constitutions and Legislation in Malta 1914 - 1964

CONSTITUTIONS AND LEGISLATION IN MALTA 1914 - 1964 volume 1: 1914-1933 Constitutions and Legislation in Malta 1914 - 1964 volume 1: 1914-1933 Raymond Mangion Published by russell square publishing limited Russell Square Publishing Limited was founded with the objective of furthering legal research and scholarship © 2016 Russell Square Publishing Limited Linguistic revision, editing, and mise en forme by Professor James J. Busuttil A.B. (Harv), J.D. (NYU), D.Phil. (Oxon) for and on behalf of Russell Square Publishing Limited The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Russell Square Publishing Limited (maker) First published 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of Russell Square Publishing Limited, or as expressly permitted by law. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to Russell Square Publishing Limited, at the address above British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data Available Printed on demand in the European Union ISBN: 978-1-911301-01-1 The photo on the cover showing the Council Chamber in the Palace in Valletta, Malta, courtesy of Dr Anthony Abela Medici. To Joan TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT THE AUTHOR xi ABBREVIATIONS xiii TABLE OF LEGISLATION Malta xxix United Kingdom xxxvi TABLE OF CASES Malta xxxix United Kingdom xl LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS xli FOREWORD 3 PART I - PROLOGUE 11 CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 11 1.1. SOURCES 11 1.2. AIM 13 1.3. METHOD 14 CHAPTER 2. THE BACKGROUND, 1814-1914 17 2.1. -

Awards Season Hilton Malta Receives the Luxairtours Quality Award

ISSUE 06 AWARDS SEASON Hilton Malta receives the Luxairtours Quality Award HILTON AMSTERDAM THE SUMMER MAN Alive with Originality An interview with Assistant Leisure Manager, Martin Bugeja Orange bikini at Luxury Outlet; Marco Bicego jewellery at Diamonds International HILTONCALLING 01 HILTONCALLING 01 HILTONCALLING 03 HILTONCALLING 05 designandtechnology. radiomir 1940 3 days automatic oro rosso (ref. 573) MALTA - 12, Republic Street, Valletta panerai.com 065630-Tecnico-DP-PAM573_420x297.indd 1 13/04/15 14:59 designandtechnology. radiomir 1940 3 days automatic oro rosso (ref. 573) MALTA - 12, Republic Street, Valletta panerai.com HILTONCALLING 07 065630-Tecnico-DP-PAM573_420x297.indd 1 13/04/15 14:59 08 HILTONCALLING WELCOME ear Guests and friends of Hilton Malta, welcome to carried out by our teams and the warm welcome of our this sixth edition of our magazine. Front Desk and Guest Relations ‘ambassadors’. The In my last message to you, I revealed to you that ambitious refurbishment projects being undertaken this year our plans for the refurbishment of our ‘Classic’ style are the most recent in a long list of achievements. We look rooms were on track. Well, it is my great pleasure to forward to celebrating many more milestone anniversaries share with you our satisfaction at the fact that many of with our owners, with our team members, and with you, these rooms are now completed, and a large number our guests and patrons, who have always been very Dof others are gradually taking shape. We are delighted encouraging with your feedback and your loyalty. with the new, vibrant, refreshed look, and we are confident that our guests will also enjoy calling these rooms ‘home’ One thing we are mindful of is that our year-on-year success during their leisure or business trips to Malta. -

Constitutions and Legislation in Malta 1914 - 1964

CONSTITUTIONS AND LEGISLATION IN MALTA 1914 - 1964 volume 2: 1933-1964 Constitutions and Legislation in Malta 1914 - 1964 volume 2: 1933-1964 Raymond Mangion Published by russell square publishing limited Russell Square Publishing Limited was founded with the objective of furthering legal research and scholarship © 2016 Russell Square Publishing Limited Linguistic revision, editing, and mise en forme by Professor James J. Busuttil A.B. (Harv), J.D. (NYU), D.Phil. (Oxon) for and on behalf of Russell Square Publishing Limited The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Russell Square Publishing Limited (maker) First published 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of Russell Square Publishing Limited, or as expressly permitted by law. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to Russell Square Publishing Limited, at the address above British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data Available Printed on demand in the European Union ISBN: 978-1-911301-02-8 The photo on the cover, courtesy of Manwel Sammut, shows the Auberge d’Auvergne, Valletta, Malta, in which the Law Courts of Malta met during the relevant period and which was destroyed during World War Two. To Bernardette TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT THE AUTHOR xi ABBREVIATIONS xiii TABLE OF LEGISLATION xxix Malta xxix United Kingdom xxxvii TABLE OF CASES xxxix Malta xxxix United Kingdom xxxix LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS xli FOREWORD 3 PART III - CROWN COLONY RULE AND QUALIFIED REPRESENTATIVE GOVERNMENT, 1933-1947 5 CHAPTER 8.