Canadian Review 01'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mill‑PARLAMENT

Nr 25 Diċembru 2020 December 2020 PARLAMENT TA’ MALTA mill‑PARLAMENT Perjodiku maħruġ mill‑Uffiċċju tal‑Ispeaker Periodical issued by the Office of the Speaker 1 mill-PARLAMENT - Diċembru 2020 Għotja demm... servizz soċjali mill-poplu għall-poplu Inħeġġuk biex nhar il-Ħamis, 6 ta’ Mejju 2021 bejn it-8:30am u s-1:00pm tiġi quddiem il-bini tal-Parlament biex tagħmel donazzjoni ta’ demm. Tinsiex iġġib miegħek il-karta tal-identità. Minħabba l-imxija tal-COVID-19, qed jittieħdu l-miżuri kollha meħtieġa biex tkun protett inti u l-professjonisti li se jkunu qed jassistuk. Jekk ħadt it-tilqima kontra l-COVID-19 ħalli 7 ijiem jgħaddu qabel tersaq biex tagħti d-demm. Din l-attività qed tittella’ miċ-Ċentru tal-Għoti tad-Demm b’kollaborazzjoni mas- Servizz Parlamentari u d-Dipartiment tas-Sigurtà Soċjali. Ħarġa Nru 25/Issue No. 25 3 Daħla Diċembru 2020/December 2020 Foreword 4 Attivitajiet tal-Parlament Parliamentary Activities Ippubblikat mill‑Uffiċċju tal‑Ispeaker Published by the Office of the Speaker 12 Il-Kumitat Permanenti Għall-Affarijiet ta’ Għawdex Bord Editorjali The Standing Committee on Gozo Affairs Editorial Board 14 Attivitajiet Internazzjonali Ray Scicluna International Activities Josanne Paris 16 Il-Kuxjenza u l-Membri Parlamentari Maltin Ancel Farrugia Migneco Conscience and the Maltese Members of Parliament Eleanor Scerri Eric Frendo 32 L-Elezzjonijiet F’Malta ta’ qabel l-Indipendenza 1836-1962 Elections in Pre-Independence Malta 1836-1962 Indirizz Postali Postal Address House of Representatives Freedom Square Valletta VLT 1115 -

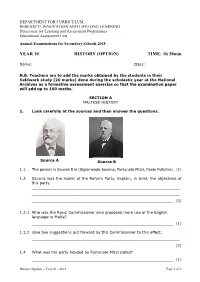

Directorate for Quality and Standards in Education

DEPARTMENT FOR CURRICULUM, RESEARCH, INNOVATION AND LIFELONG LEARNING Directorate for Learning and Assessment Programmes Educational Assessment Unit Annual Examinations for Secondary Schools 2018 YEAR 10 HISTORY (OPTION) TIME: 1h 30min Name: _____________________________________ Class: _______________ N.B. Teachers are to add the marks obtained by the students in their fieldwork study (20 marks) done during the scholastic year at the National Archives as a formative assessment exercise so that the examination paper will add up to 100 marks. SECTION A MALTESE HISTORY 1. Look carefully at the sources and then answer the questions. Source A Source B 1.1 The person in Source B is (Sigismondo Savona, Fortunato Mizzi, Paolo Pullicino). (1) 1.2 Savona was the leader of the Reform Party. Explain, in brief, the objectives of this party. _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________ (3) 1.3.1 Who was the Royal Commissioner who proposed more use of the English language in Malta? ____________________________________________________________ (1) 1.3.2 Give two suggestions put forward by this Commissioner to this effect. _______________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________ (2) 1.4 What was the party headed by Fortunato Mizzi called? ____________________________________________________________ (1) History (Option) – Year 10 – 2018 Page 1 of -

I Know It's Not Racism, but What Is It?

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Law Faculty Articles and Essays Faculty Scholarship 1-1986 I Know It's Not Racism, But What Is It? Michael H. Davis Cleveland-Marshall College of Law, Cleveland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/fac_articles Part of the Religion Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Repository Citation Davis, Michael H., "I Know It's Not Racism, But What Is It?" (1986). Law Faculty Articles and Essays. 758. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/fac_articles/758 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Articles and Essays by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Know It's Not Racism, But. What Is It? by MICHAEL H. DAVIS y memories are so dim, I don't know whether as she stared at his face "we're n ot moving. Why M what I remember is the event itself or the fre would we move? We've o~ly been here a short time." quent amused retelling of it by my mother. But on "But, Mrs. Davis," he asked my mother, "haven't May 14, 1948, when I was two years old, the mailman you heard the news?" came to my family's door in our small Massachusetts Wordless, .her frown only grew. town in which we were the only Jews. "The Jews," he announced. -

Politics, Religion and Education in Nineteenth Century Malta

Vol:1 No.1 2003 96-118 www.educ.um.edu.mt/jmer Politics, Religion and Education in Nineteenth Century Malta George Cassar [email protected] George Cassar holds the post of lecturer with the University of Malta. He is Area Co- ordinator for the Humanities at the Junior College where he is also Subject Co-ordinator in- charge of the Department of Sociology. He holds degrees from the University of Malta, obtaining his Ph.D. with a thesis entitled Prelude to the Emergence of an Organised Teaching Corps. Dr. Cassar is author of a number of articles and chapters, including ‘A glimpse at private education in Malta 1800-1919’ (Melita Historica, The Malta Historical Society, 2000), ‘Glimpses from a people’s heritage’ (Annual Report and Financial Statement 2000, First International Merchant Bank Ltd., 2001) and ‘A village school in Malta: Mosta Primary School 1840-1940’ (Yesterday’s Schools: Readings in Maltese Educational History, PEG, 2001). Cassar also published a number of books, namely, Il-Mużew Marittimu Il-Birgu - Żjara edukattiva għall-iskejjel (co-author, 1997); Għaxar Fuljetti Simulati għall-użu fit- tagħlim ta’ l-Istorja (1999); Aspetti mill-Istorja ta’ Malta fi Żmien l-ingliżi: Ktieb ta’ Riżorsi (2000) (all Għaqda ta’ l-Għalliema ta’ l-Istorja publications); Ġrajja ta’ Skola: L-Iskola Primarja tal-Mosta fis-Sekli Dsatax u Għoxrin (1999) and Kun Af il-Mosta Aħjar: Ġabra ta’ Tagħlim u Taħriġ (2000) (both Mosta Local Council publications). He is also researcher and compiler of the website of the Mosta Local Council launched in 2001. Cassar is editor of the journal Sacra Militia published by the Sacra Militia Foundation and member on The Victoria Lines Action Committee in charge of the educational aspects. -

Beyond Electoralism: Reflections on Anarchy, Populism, and the Crisis of Electoral Politics

This is a repository copy of Beyond electoralism: reflections on anarchy, populism, and the crisis of electoral politics. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/124741/ Version: Published Version Article: Araujo, E., Ferretti, F., Ince, A. et al. (5 more authors) (2017) Beyond electoralism: reflections on anarchy, populism, and the crisis of electoral politics. ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies, 16 (4). pp. 607-642. ISSN 1492-9732 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Beyond Electoralism: Reflections on anarchy, populism, and the crisis of electoral politics A Collective of Anarchist Geographers Erin Araujo, Memorial University of Newfoundland Federico Ferretti, University College Dublin Anthony Ince, Cardiff University Kelvin Mason, para-academic Joshua Mullenite, Florida International University Jenny Pickerill, University of Leicester Toby Rollo, University of British Columbia Richard J White, Sheffield Hallam University [email protected] Abstract This paper is comprised of a series of short, conversational or polemical interventions reflecting on the political ‘moment’ that has emerged in the wake of the rise of right-populist politics, particularly in the Global North. -

Research on American Nationalism: Review of the Literature, Annotated Bibliography, and Directory of Publicly Available Data Sets

Research on American Nationalism: Review of the Literature, Annotated Bibliography, and Directory of Publicly Available Data Sets Bart Bonikowski Princeton University May 1, 2008 With a Preface by Paul DiMaggio Financial support from the Russell Sage Foundation, and helpful advice in identifying the relevant scholarly literature from Rogers Brubaker, Andrew Perrin, Wendy Rahn, Paul Starr, and Bob Wuthnow, are gratefully acknowledged. Preface Bart Bonikowski has produced an invaluable resource for scholars and students interested in American nationalism. His essay reviewing the literature in the field, the annotated bibliography that follows, and the inventory of data sets useful for the study of American nationalism constitute a sort of starter kit for anyone interested in exploring this field. As Mr. Bonikowski points out, relatively few scholars have addressed “American nationalism” explicitly. Much research on nationalism takes as its object movements based on a fiction of consanguinity, and even work that focuses on “civic” or “creedal” nationalism has often treated the United States as a marginal case. Indeed, part of the U.S.’s civic nationalist creed is to deny that there is such a thing as “American national- ism.” Americans, so the story goes, are patriotic; nationalism is foreign and exotic, something for Europe or the global South. The reality, of course, is not so simple. Both historical and social-scientific re- search demonstrates a strong tradition of ethnocultural nationalism in the U.S., providing evidence that Americans of other than European descent have often been perceived as less fully “American” than white Christians of northern European origin. Moreover, nat- ionalism need not be defined solely in ethnocultural terms. -

History in the College of Arts and Letters

History In the College of Arts and Letters OFFICE: Arts and Letters 588 The training in basic skills and the broad range of knowledge TELEPHONE: 619-594-5262 / FAX: 619-594-2210 students receive in history courses prepare history majors for a wide variety of careers in law, government, politics, journalism, publishing, http://www-rohan.sdsu.edu/dept/histweb/dept.html private charities and foundations, public history, business, and science. Teaching at the primary to university levels also offers oppor- Faculty tunity for history majors who continue their education at the graduate level. Emeritus: Bartholomew, Jr., Cheek, Christian, Chu, Cox, Cunniff, Davies, DuFault, Dunn, Filner, Flemion, Hamilton, Hanchett, Heinrichs, Heyman, Hoidal, Kushner, McDean, Norman, O’Brien, Impacted Program Polich, Schatz, Smith, C., Smith, R., Starr, Stites, Stoddart, Strong, The history major is an impacted program. To be admitted to the Vanderwood, Vartanian, Webb history major, students must meet the following criteria: Chair: Ferraro a. Complete with a minimum GPA of 2.20 and a grade of C or The Dwight E. Stanford Chair in American Foreign Relations: higher: History 100, 101, and six units selected from History HIST Cobbs Hoffman 105, 106, 109, or 110. These courses cannot be taken for The Nasatir Professor of Modern Jewish History: Baron credit/no credit (Cr/NC); Professors: Baron, Cobbs Hoffman, Ferraro, Kornfeld, Kuefler, Wiese b. Complete a minimum of 60 transferable semester units; Associate Professors: Beasley, Blum, Colston, DeVos, Edgerton- Tarpley, Elkind, Passananti, Pollard, Putman, Yeh c. Have a cumulative GPA of 2.40 or higher. Assistant Professors: Abalahin, Campbell, Penrose To complete the major, students must fulfill the degree requirements Lecturers: Crawford, DiBella, Guthrie, Hay, Kenway, for the major described in the catalog in effect at the time they are Mahdavi-Izadi, Nobiletti, Roy, Ysursa accepted into the premajor at SDSU (assuming continuous enrollment). -

Maltese Immigrants in Detroit and Toronto, 1919-1960

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Britishers in Two Worlds: Maltese Immigrants in Detroit and Toronto, 1919-1960 Marc Anthony Sanko Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Sanko, Marc Anthony, "Britishers in Two Worlds: Maltese Immigrants in Detroit and Toronto, 1919-1960" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6565. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6565 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Britishers in Two Worlds: Maltese Immigrants in Detroit and Toronto, 1919-1960 Marc Anthony Sanko Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Kenneth Fones-Wolf, Ph.D., Chair James Siekmeier, Ph.D. Joseph Hodge, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Mary Durfee, Ph.D. Department of History Morgantown, West Virginia 2018 Keywords: Immigration History, U.S. -

Jingoism, Warmongering, Racism

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction Jingoism, Warmongering, Racism Of the many interconnected riddles that the Indian Mutiny of 1857–59 poses to a historian of nineteenth-century culture, the primary one is this: why did contemporaries consider it an event of epochal importance? Gauged purely in the light of its empirical scale and its practical conse quences, the Mutiny might not seem an outstandingly momentous histori cal event. The two-year campaign waged by the British “Army of Retribu tion” against the 1857 rebellion of Indian mercenary troops did prove to be a harrowing and sanguinary one, a struggle marked on both sides “by a ferocity for which even the ordinary depravity of human nature cannot account” (Grant and Knollys 1) and which contemporaries sought per plexedly to explain to themselves. Nor should the war be considered a trivial episode, either militarily or in terms of its possible consequences for national and global politics. Undoubtedly, as John Colvin, the lieutenant governor of the North-Western Provinces, said at the time, “the safety of the Empire was imperilled” and “a crisis in our fortunes had arrived, the like of which had not been seen for a hundred years” (qtd. Kaye 3:196– 97). “The terrible Mutiny,” said General Hope Grant, “for a time, had shaken the British power in India to its foundation” (Grant and Knollys 334). Had the large, well-trained, and (except for the crucial lack of mod ern rifles) well-equipped but poorly led rebel armies prevailed, and had the rebels achieved their goal of effecting, in the words of one rebel leader, “the complete extermination of the infidels from India” (Kaye 3:275), the result would have been a catastrophe for Britain. -

Parlament Ta' Malta

Nr 8 Marzu 2015 March 2015 PARLAMENT TA’ MALTA mill‑PARLAMENT Perjodiku maħruġ mill‑Uffiċċju tal‑Ispeaker Periodical issued by the Office of the Speaker mill-PARLAMENT - Marzu 2015 Kors ta’ tifi tan-nar mill-Protezzjoni Ċivili lill-istaff The staff of the Maltese Parliament during a fire tal-Parlament bi tħejjija għad-dħul fil-bini il-ġdid extinguishing course given by the Civil Protection, in tal-Parlament. preparation for the entry into Parliament’s new building. Ħarġa Nru 8/Issue No. 3 Daħla Marzu 2015/March 2015 Foreword Ippubblikat mill‑Uffiċċju tal‑Ispeaker 4 L-Onorarju tal-Membri Eletti: Għadma ta’ tilwim minn Published by the Office of the Speaker Għanqudu The Honorarium of the Elected Members: A Veritable Bone of Bord Editorjali Contention from the Womb Editorial Board Ray Scicluna Josanne Paris 8 Attivitajiet tal-Parlament Ancel Farrugia Migneco Activities in Parliament Eleanor Scerri Sarah Gauci Eric Frendo 12 Ħarsa ġenerali lejn l-iżvilupp tal-partiti politiċi f’Malta kolonjali (1800-1964) Indirizz Postali An overview of the political parties in colonial Malta (1800-1964) Postal Address House of Representatives 18 Attivitajiet Internazzjonali Republic Street International Activities Valletta VLT 1115 Malta +356 2559 6000 Qoxra: Veduta tal-bitħa tal-Palazz www.parlament.mt Cover: Bird’s eye view of the Palace courtyard [email protected] Ritratti/Photos: ISSN 2308‑538X Parlament ta’ Malta/DOI ISSN (online) 2308‑6637 2 Marzu 2015 mill-PARLAMENT - Daħla Foreword Dawn l-aħħar tliet xhur, bejn Jannar u l-aħħar ta’ Marzu These last three months, between January and the end ta’ din is-sena, kienu xhur impenjattivi ħafna għal dan of March of this year, were very demanding months il-Parlament. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Abrams, Ruth. ‘Jewish Women in the International Woman Suffrage Alliance, 1899–1926’. PhD diss., Brandeis University, 1997. Abse, Leo. ‘A Tale of Collaboration not Conflict with the “People of the Book” ’. Review of The Jews of South Wales, ed. Ursula Henriques. New Welsh Review, 6.2 (1993): 16–21. Ackroyd, Peter. London: The Biography. London: Chatto & Windus, 2001. Alderman, Geoffrey. ‘The Anti-Jewish Riots of August 1911 in South Wales’. Welsh History Review, 6.2 (1972): 190–200. ———. ‘The Jew as Scapegoat? The Settlement and Reception of Jews in South Wales before 1914’. Jewish Historical Society of England: Transactions, 26 (1974–78): 62–70. ———. Modern British Jewry. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992. Alleyne, Brian. ‘An Idea of Community and Its Discontents: Towards a More Reflexive Sense of Belonging in Multicultural Britain’. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 25.4 (2002): 607–627. Arata, Stephen D. ‘The Occidental Tourist: Dracula and the Anxiety of Reverse Colonization’. Victorian Studies, 33.4 (1990): 62–45. Avineri, Shlomo. ‘Theodor Herzl’s Diaries as a Bildungsroman’. Jewish Social Studies, 5.3 (1999): 1–46. Avitzur, Shmuel. The Industry of Action: A Collection on the History of Israeli Industry, in Commemoration of Nahum Wilbusch, Pioneer of the New Hebrew Industry in Israel. Tel-Aviv: Milo, 1974. [Hebrew]. Back, Les. New Ethnicities and Urban Culture: Racisms and Multiculture in Young Lives. London: Routledge, 1996. Bakhtin, Mikhail. Rabelais and His World. Trans. Helene Iswolsky. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1968. Bar-Avi, Israel. Dr Moses Gaster. Jerusalem: Cénacle Littéraire ‘Menorah’, 1973. Bareli, Avi. ‘Forgetting Europe: Perspectives on the Debate about Zionism and Colonialism’. -

Maltese Colonial Identity: Latin Mediterranean Or British Empire?

The British Colonial Experience 1800-1964 The Impact on Maltese Society Edited by Victor Mallia-Milanes 2?79G ~reva Publications Published under the auspices of The Free University: Institute of Cultural Anthropology! Sociology of Development Amsterdam 10 HENRY FRENDO Maltese Colonial Identity: Latin Mediterranean or British Empire? Influenced by history as much as by geography, identity changes, or develops, both as a cultural phenomenon and in relation to economic factors. Behaviouristic traits, of which one may not be conscious, assume a different reality in cross-cultural interaction and with the passing of time. The Maltese identity became, and is, more pronounced than that of other Mediterranean islanders from the Balearic to the Aegean. These latter spoke varieties of Spanish and Greek in much the same way as the inhabitants of the smaller islands of Pantalleria, Lampedusa, or Elba spoke Italian dialects and were absorbed by the neighbouring larger mainlands. The inhabitants of modern Malta, however, spoke a language derived from Arabic at the same time as they practised the Roman Catholic faith and were exposed, indeed subjected, to European iDfluences for six or seven centuries, without becoming integrated with their closest terra firma, Italy.l This was largely because of Malta's strategic location between southern Europe and North Mrica. An identifiable Maltese nationality was thus moulded by history, geography, and ethnic admixture - the Arabic of the Moors, corsairs, and slaves, together with accretions from several northern and southern European races - from Normans to Aragonese. Malta then passed under the Knights of St John, the French, and much more importantly, the British.