The Road to Women's Suffrage and Beyond Women's Enfranchisement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

It-T a Bib Pawlu Boffa K.B., O.B.E

Soc. Fil. Nicolo /souard- Mosta 2000 Profil ta' Personagg magfiruf: It-T abib Pawlu Boffa K.B., o.B.E. (1890- 1962) minn F. DEGUARA awlu Boffa twieled il-Birgu fit-30 ta' Gunju 1890. Missieru kien mghallem tal-haddieda fit-Tarzna. Pawlu P mar 1-iskola Primarja, attenda 1-LiCeo u 1-Universita mnejn lahag tabib fl-1913. Matull-ewwel gwerra dinjija tal-1914-1918, huwa hadem bhala tabib mar-Royal Medical Corps f'Malta, Salonika fil-Grecja u fug il vapuri sptarijiet Inglizi. Wara 1-gwerra, kien serva bhala tabib privat f'Rahal Gdid. Il-Prokuratur Legali Guze Borg Fil-laggha tal-gradwati fl -1932, Pantalleresco, li kien 1-ahhar Boffa ried jitkellem bil-Malti u gie Segretarju tax-Xirka tal-lmdawlin mwaggaf mill-President, izda Boffa ta' Manwel Dimech fl-1914, kien kompla jhaggagha li ghandu 1-jedd irrakkonta li missier Boffa, li kien jitkellem bil-Malti meta f'dagga dimekkjan, kien galilhom li meta wahda deputat Nazzjonalista, ibnu jsir tabib jaghmluh it-tabib tax- gradwat ukoll, garalu siggu. Boffa xirka. Imma meta fil -fatt lahag warrabblu biex jiskansah u dabbar tabib, Dr. Boffa la ried jaf b 'Dimech id-dagga go rasu x-xwejjah 1-A vukat u angas bix-Xirka! Guze Fenech, Stricklandjan, li min It-Tabib Pawlu Boffa resag lejn jaf kemm tkellem tajjeb bil-Malti! il-Partit tal-Haddiema fl-1923 u Dr.Boffaspikkasewwafizmien hareg ghall-elezzjoni tal-1924 u gie il-kwistjoni politiko-religjuza, tant li elett taht 1-Amery-Milner kemm tal-Partit Nazzjonalista kif Constitution. Tela' wkoll fl-1927 ukoll 1-Klerikali kienu jghajruh u fforma parti mill-koalizzjoni bejn mhux ftit li huwa socjalist u il-Partit Laburista u 1-Partit ta' Lord kommunist u sahansitra galu li kien Strickland, maghrufa bhala gal li fetah hafna nies (ghax kien Compact. -

Licensed ELT Schools in Malta and Gozo

A CLASS ACADEMY OF ENGLISH BELS GOZO EUROPEAN SCHOOL OF ENGLISH (ESE) INLINGUA SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES St. Catherine’s High School, Triq ta’ Doti, ESE Building, 60, Tigne Towers, Tigne Street, 11, Suffolk Road, Kercem, KCM 1721 Paceville Avenue, Sliema, SLM 3172 Mission Statement Pembroke, PBK 1901 Gozo St. Julian’s, STJ 3103 Tel: (+356) 2010 2000 Tel: (+356) 2137 4588 Tel: (+356) 2156 4333 Tel: (+356) 2137 3789 Email: [email protected] The mission of the ELT Council is to foster development in the ELT profession and sector. Malta Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Web: www.inlinguamalta.com can boast that both its ELT profession and sector are well structured and closely monitored, being Web: www.aclassenglish.com Web: www.belsmalta.com Web: www.ese-edu.com practically the only language-learning destination in the world with legislation that assures that every licensed school maintains a national quality standard. All this has resulted in rapid growth for INSTITUTE OF ENGLISH the sector. ACE ENGLISH MALTA BELS MALTA EXECUTIVE TRAINING LANGUAGE STUDIES Bay Street Complex, 550 West, St. Paul’s Street, INSTITUTE (ETI MALTA) Mattew Pulis Street, Level 4, St.George’s Bay, St. Paul’s Bay ESE Building, Sliema, SLM 3052 ELT Schools St. Julian’s, STJ 3311 Tel: (+356) 2755 5561 Paceville Avenue, Tel: (+356) 2132 0381 There are currently 37 licensed ELT Schools in Malta and Gozo. Malta can boast that both its ELT Tel: (+356) 2713 5135 Email: [email protected] St. Julian’s, STJ 3103 Email: [email protected] profession and sector are well structured and closely monitored, being the first and practically only Email: [email protected] Web: www.belsmalta.com Tel: (+356) 2379 6321 Web: www.ielsmalta.com language-learning destination in the world with legislation that assures that every licensed school Web: www.aceenglishmalta.com Email: [email protected] maintains a national quality standard. -

MHA Newsletter March 2015

MHA Newsletter No. 2/2015 www.mha.org.au March 2015 Merħba! A warm welcome to all the members and Submerged Lowlands settled by early humans June 2014 friends of the Maltese Historical Association. much earlier than the present mainland. June 2014 Our February lecture on Maltese politics since 1947, by English scientists tested samples of sediment recovered Dr Albert Farrugia was well attended. As I do not by archaeologists from an underwater Mesolithic Stone usually have a great interest in politics, I did not think it Age site, off the coast of the Isle of Wight. They would be very interesting. I was pleased to be proved discovered DNA from einkorn, an early form of wheat. totally wrong: it was absolutely fascinating! A summary Archeologists also found evidence of woodworking, is contained in this newsletter. Our next lecture, on 17 cooking and flint tool manufacturing. Associated March, will be given by Professor Maurice Cauchi on the material, mainly wood fragments, was dated to history of Malta through its monuments. On 21 April, between 6010 BC and 5960 BC. These indicate just before the ANZAC day weekend, Mario Bonnici will Neolithic influence 400 years earlier than proximate discuss Malta’s involvement in the First World War. European sites and 2000 years earlier than that found on mainland Britain! In this newsletter you will also find an article about how an ancient site discovered off the coast of England may The nearest area known to have been producing change how prehistory is looked at; a number of einkorn by 6000 BC is southern Italy, followed by France interesting links; an introduction to Professor Cauchi’s and eastern Spain, who were producing it by at least lecture; coming events of interest; Nino Xerri’s popular 5900 BC. -

Politiker, Präsident Von Malta Biographie Barbara, Agatha (Zabbar

Report Title - p. 1 of 6 Report Title Adami, Edward Fenech (Birkirkara, Malta 1934-) : Politiker, Präsident von Malta Biographie 1994 Edward Fenech Adami besucht China. [ChiMal3] Barbara, Agatha (Zabbar, Malta 1923-2002 Zabbar) : Politikerin, Präsidentin von Malta Biographie 1985 Agatha Barbara besucht China. [ChiMal3] Borg, Joseph = Borg, Joe (Malta 1953-) : Politiker Biographie 2000 Joseph Borg besucht China. [ChiMal3] Chen, Zhimai (1908-1978) : Chinesischer Diplomat Biographie 1944 Chen Zhimai ist Counselor der chinesischen Botschaft in Washington, D.C. [ChiMal1] 1959-1966 Chen Zhimai ist Botschafter der chinesischen Botschaft in Canberra, Australien und in New Zealand. [ChiCan1,ChiAus2] 1969 Chen Zhimai ist Botschafter im Vatikan, Italien. [ChiMal1] 1971 Chen Zhimai ist Botschafter in Valletta, Malta. [ChiMal1] Cheng, Zhiping (um 1983) : Chinesischer Diplomat Biographie 1977-1983 Cheng Zhiping ist Botschafter der chinesischen Botschaft in Valletta, Malta. [ChiMal1] Falzon, Alfred J. (um 1982) : Maltesischer Diplomat Biographie 1981-1982 Alfred J. Falzon ist Botschafter der maltesischen Botschaft in Beijing. [ChiMal2] Forace, Joseph Lennard (Valletta, Malta 1925-2005) : Diplomat Biographie 1972-1978 Joseph Lennard ist Botschafter der maltesischen Botschaft in Beijing. [ChiMal2] Gonzi, Lawrence (Valletta 1953-) : Politiker, Premierminister von Malta Biographie 1996 Lawrence Gonzi besucht China. [ChiMal3] 2000 Lawrence Gonzi besucht China. [ChiMal3] Report Title - p. 2 of 6 Guo, Jiading (um 1993) : Chinesischer Diplomat Biographie 1983-1993 -

Mill‑PARLAMENT

Nr 25 Diċembru 2020 December 2020 PARLAMENT TA’ MALTA mill‑PARLAMENT Perjodiku maħruġ mill‑Uffiċċju tal‑Ispeaker Periodical issued by the Office of the Speaker 1 mill-PARLAMENT - Diċembru 2020 Għotja demm... servizz soċjali mill-poplu għall-poplu Inħeġġuk biex nhar il-Ħamis, 6 ta’ Mejju 2021 bejn it-8:30am u s-1:00pm tiġi quddiem il-bini tal-Parlament biex tagħmel donazzjoni ta’ demm. Tinsiex iġġib miegħek il-karta tal-identità. Minħabba l-imxija tal-COVID-19, qed jittieħdu l-miżuri kollha meħtieġa biex tkun protett inti u l-professjonisti li se jkunu qed jassistuk. Jekk ħadt it-tilqima kontra l-COVID-19 ħalli 7 ijiem jgħaddu qabel tersaq biex tagħti d-demm. Din l-attività qed tittella’ miċ-Ċentru tal-Għoti tad-Demm b’kollaborazzjoni mas- Servizz Parlamentari u d-Dipartiment tas-Sigurtà Soċjali. Ħarġa Nru 25/Issue No. 25 3 Daħla Diċembru 2020/December 2020 Foreword 4 Attivitajiet tal-Parlament Parliamentary Activities Ippubblikat mill‑Uffiċċju tal‑Ispeaker Published by the Office of the Speaker 12 Il-Kumitat Permanenti Għall-Affarijiet ta’ Għawdex Bord Editorjali The Standing Committee on Gozo Affairs Editorial Board 14 Attivitajiet Internazzjonali Ray Scicluna International Activities Josanne Paris 16 Il-Kuxjenza u l-Membri Parlamentari Maltin Ancel Farrugia Migneco Conscience and the Maltese Members of Parliament Eleanor Scerri Eric Frendo 32 L-Elezzjonijiet F’Malta ta’ qabel l-Indipendenza 1836-1962 Elections in Pre-Independence Malta 1836-1962 Indirizz Postali Postal Address House of Representatives Freedom Square Valletta VLT 1115 -

Trainers Manual

Together in Malta – Trainers Manual 1 Table of Contents List of Acronyms 3 Introduction 4 Proposed tools for facilitators of civic orientation sessions 6 What is civic orientation? 6 The Training Cycle 6 The principles of adult learning 7 Creating a respectful and safe learning space 8 Ice-breakers and introductions 9 Living in Malta 15 General information 15 Geography and population 15 Political system 15 National symbols 16 Holidays 17 Arrival and stay in Malta 21 Entry conditions 21 The stay in the country 21 The issuance of a residence permit 21 Minors 23 Renewal of the residence permit 23 Change of residence permit 24 Personal documents 24 Long-term residence permit in the EU and the acquisition of Maltese citizenship 24 Long Term Residence Permit 24 Obtaining the Maltese citizenship 25 Health 26 Access to healthcare 26 The National Health system 26 What public health services are provided? 28 Maternal and child health 29 Pregnancy 29 Giving Birth 30 Required and recommended vaccinations 30 Contraception 31 Abortion and birth anonymously 31 Women’s health protection 32 Prevention and early detection of breast cancer 32 Sexually transmitted diseases 32 Anti violence centres 33 FGM - Female genital mutilation 34 School life and adult education 36 IOM Malta 1 De Vilhena Residence, Apt. 2, Trejqet il-Fosos, Floriana FRN 1182, Malta Tel: +356 2137 4613 • Fax: +356 2122 5168 • E-mail: [email protected] • Internet: http://www.iom.int 2 Malta’s education system 36 School Registration 37 Academic / School Calendar 38 Attendance Control 38 -

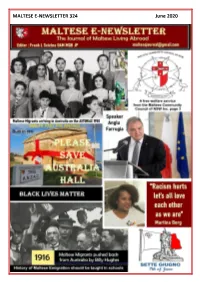

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 324 June 2020 1

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 324 June 2020 1 MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 324 June 2020 The Black Menace - When the Maltese Migrants were pushed back from Australia by Billy Hughes In 1916, Malta was a poor island, heavily caught up in WWI. It was “the nurse of the Mediterranean”, taking care of 80,000 wounded soldiers, a lot of them Australian. They were shipped in from Gallipoli and other European fronts, where Maltese men were fighting on the side of the British Empire themselves. For a small place, with only a little over 210,000 inhabitants, Malta went above and beyond, and many Australian returned soldiers were grateful. But that didn’t help the Maltese in 1916. When the Gange arrived in WA, Australia was in the grip of a referendum on conscription. Labor Prime Minister Billy Hughes, whose enthusiasm for the war had earned him the moniker “the little digger”, had become worried when the zeal to enlist had dropped off after alarming news of tens of thousands of deaths had been published. His solution was to try and see if he could force men to join the military, but for that he needed the permission of the Australian people. On the 28th of October 1916, there was to be a referendum that asked if they were okay with that. In the lead-up, the country had been split down the middle. Scared of conscription were the unions, who feared that with their members away at the front, their jobs would be taken over by women, or even worse, coloured people. -

The Current Situation of Gender Equality in Malta – Country Profile

15 The current situation of gender equality in Malta – Country Profile 2012 This country fiche was financed by, and prepared for the use of the European Commission, Directorate-General Justice, Unit D2 “Gender Equality” in the framework of the service contract managed by Roland Berger Strategy Consultants GmbH in partnership with ergo Unternehmenskommunikation GmbH & Co. KG. It does not necessarily reflect the opinion or position of the European Commission, Directorate-General Justice neither the Commission nor any person acting on its behalf is responsible for the use that might be made of the information contained in this publication. Table of Content 148 Foreword ......................................................................................................... 03 Management Summary .................................................................................... 04 1. How Maltese companies access the talent pool ........................................... 05 1.1 General participation of women and men in the labour market ............. 05 1.2 Part-time segregation of women and men ............................................. 06 1.3 Qualification level and choice of education of women and men .............. 08 1.4 Under-/overrepresentation of women and men in occupations or sectors – " Horizontal segregation"..................................................................... 09 1.5 Under-/overrepresentation of women and men in hierarchical levels – "Vertical segregation" ........................................................................... -

Archbishop Michael Gonzi, Dom Mintoff, and the End of Empire in Malta

1 PRIESTS AND POLITICIANS: ARCHBISHOP MICHAEL GONZI, DOM MINTOFF, AND THE END OF EMPIRE IN MALTA SIMON C. SMITH University of Hull The political contest in Malta at the end of empire involved not merely the British colonial authorities and emerging nationalists, but also the powerful Catholic Church. Under Archbishop Gonzi’s leadership, the Church took an overtly political stance over the leading issues of the day including integration with the United Kingdom, the declaration of an emergency in 1958, and Malta’s progress towards independence. Invariably, Gonzi and the Church found themselves at loggerheads with the Dom Mintoff and his Malta Labour Party. Despite his uncompromising image, Gonzi in fact demonstrated a flexible turn of mind, not least on the central issue of Maltese independence. Rather than seeking to stand in the way of Malta’s move towards constitutional separation from Britain, the Archbishop set about co-operating with the Nationalist Party of Giorgio Borg Olivier in the interests of securing the position of the Church within an independent Malta. For their part, the British came to accept by the early 1960s the desirability of Maltese self-determination and did not try to use the Church to impede progress towards independence. In the short-term, Gonzi succeeded in protecting the Church during the period of decolonization, but in the longer-term the papacy’s softening of its line on socialism, coupled with the return to power of Mintoff in 1971, saw a sharp decline in the fortunes of the Church and Archbishop Gonzi. Although less overt than the Orthodox Church in Cyprus, the power and influence of the Catholic Church in Malta was an inescapable factor in Maltese life at the end of empire. -

Malta and Ten Years of Eu Membership: How Tenacious Was the Island?

MALTA AND TEN YEARS OF EU MEMBERSHIP: HOW TENACIOUS WAS THE ISLAND? Roderick Pace Malta and Ten Years of EU Membership: How tenacious was the Island? (L-Università ta’ Malta) Roderick Pace SUMMARY: I. INTRODUCTION: EU MEMBERSHIP AND MALTA ’S TRANSFORMA - TION.— 2. MALTA : A PHYSICAL AND POLITICAL CHARACTERIZATION.— 3. MALTA ’S POLARIZED POLITICAL SCENE AND THE DEBATE ON EU MEMBERSHIP.— 4. THE IMPACT OF EU MEMBERSHIP ON MALTA : 4.1. Changes in the Political Landscape. 4.2. Party Shifts on Neutrality . 4.3. Uploading the Immigration Burden. 4.4. Economic Effects of Membership.— 5. CONCLUDING REMARKS . RESUMEN: Dado que es difícil llevar a cabo un análisis amplio que abarque todos los aspectos de lo que diez años de integración en la Unión Europea han significado para Malta, este artículo se centra en una selección de los impactos más notable de la adhesión, precedidos por una descripción de Malta, una caracterización de su sistema político, y un análisis de la escena política, tradicionalmente polarizada, en la que se expondrán las posiciones de sus dos más importantes partidos en relación con la inte- gración del país en la UE y la OTAN. Los temas tratados incluyen los cambios en el panorama político de Malta como consecuencia de la cambiante posición de los par- tidos de Malta sobre la integración de la UE; los cambios de postura sobre la cuestión de la neutralidad; la forma en que Malta ha venido afrontando la carga de la inmigra- ción, y algunas consideraciones sobre los efectos económicos de la adhesión a la UE. PALABRAS CLAVE: Malta, Unión Europea, Ampliación de la UE, neutralidad, pola- rización. -

Unlocking the Female Potential Research Report

National Commission for the Promotion of Equality UNLOCKING THE FEMALE POTENTIAL RESEARCH Report Entrepreneurs and Vulnerable Workers in Malta & Gozo Economic Independence for the Maltese Female Analysing Inactivity from a Gender Perspective Gozitan Women in Employment xcv Copyright © National Commission for the Promotion of Equality (NCPE), 2012 National Commission for the Promotion of Equality (NCPE) Gattard House, National Road, Blata l-Bajda HMR 9010 - Malta Tel: +356 2590 3850 Email: [email protected] www.equality.gov.mt All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of research and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the author and publisher. Published in 2012 by the National Commission for the Promotion of Equality Production: Outlook Coop ISBN: 978-99909-89-44-1 2 National Commission for the Promotion of Equality FOREWORD Dear reader, NCPE’s commitment to eliminating gender equality in Malta comes forth again with this research exercise. As you will read in the following pages, through the European Social Fund project – ESF 3.47 Unlocking the Female Potential, NCPE has embarked on a mission to further understand certain realities that limit the involvement of women in the labour market. Throughout this research, we have sought to identify the needs of specific female target groups that make up the national context. -

Challenger Party List

Appendix List of Challenger Parties Operationalization of Challenger Parties A party is considered a challenger party if in any given year it has not been a member of a central government after 1930. A party is considered a dominant party if in any given year it has been part of a central government after 1930. Only parties with ministers in cabinet are considered to be members of a central government. A party ceases to be a challenger party once it enters central government (in the election immediately preceding entry into office, it is classified as a challenger party). Participation in a national war/crisis cabinets and national unity governments (e.g., Communists in France’s provisional government) does not in itself qualify a party as a dominant party. A dominant party will continue to be considered a dominant party after merging with a challenger party, but a party will be considered a challenger party if it splits from a dominant party. Using this definition, the following parties were challenger parties in Western Europe in the period under investigation (1950–2017). The parties that became dominant parties during the period are indicated with an asterisk. Last election in dataset Country Party Party name (as abbreviation challenger party) Austria ALÖ Alternative List Austria 1983 DU The Independents—Lugner’s List 1999 FPÖ Freedom Party of Austria 1983 * Fritz The Citizens’ Forum Austria 2008 Grüne The Greens—The Green Alternative 2017 LiF Liberal Forum 2008 Martin Hans-Peter Martin’s List 2006 Nein No—Citizens’ Initiative against