Leadership and Women: the Space Between Us

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Rotary Club Malta 1967 – 2007

THE HISTORY OF ROTARY CLUB MALTA 1967 – 2007 Compiled by Rotarian Robert von Brockdorff Dec 2008 © Robert Von Brockdorff 2008/9 Contents 1. Worldwide membership ................................................................................................................................ 1 2. Club Directory ................................................................................................................................................ 2 3. Club Newsletter ............................................................................................................................................. 2 4. Humour .......................................................................................................................................................... 2 5. Council decisions ............................................................................................................................................ 2 6. International Presidents in Malta .................................................................................................................. 2 7. District ............................................................................................................................................................ 3 8. Male Gender Membership ............................................................................................................................. 3 9. District Governors ......................................................................................................................................... -

Gender Concerns International Between January 14-18, Conducted a Successful Pre-Election Gender Need Assessment Mission (PGNAM) in Kyiv, Ukraine

Gender Concerns International between January 14-18, conducted a successful Pre-Election Gender Need Assessment Mission (PGNAM) in Kyiv, Ukraine. Director Sabra Bano met with Honourable Chairwomen Ms. Tetiana Slipachuk and other members of Central Election Commission. The mission met various key stakeholders to learn about the electoral processes, media coverage, engagement of civil society organisations and position of international community. Honourable Chairwomen Tetiana Slipachuk and Director Sabra Bano, Central Election Commission, Kyiv, Ukraine On Thursday 7th February, thousands of school-students confronted the government demonstrating their concerns regarding the global emission crisis. They gathered at Malieveld in the Hague and from there kept marching through the state quarters during the day. The Dutch youth are following the good practice set by their Belgian comrades who have been protesting during the last few weeks to address the severity of climate change its impact on their future. On 5th February, the Hague Hub of Geneva based The International Gender Champions (IGC) network was launched with the support of the embassies of Canada and Switzerland at the International Criminal Court (ICC), The Hague, the Netherlands. At the event Director Bano stated, “Gender Concerns International welcomes the opening of IGC The Hague Hub and ensures its cooperation and support for this initiative". On 25th January 2019, the Premiere Event for the film, Gul Makai, took place at Vue Cinema, Westfield, Ariel Way, London. The tale of Gul Makai reflects the real-life story of heroine, Malala Yousafzai which also illustrates the realities of many other girls. The Public Prosecution Service is set to investigate the Nashville Declaration regarding its potential breach of Dutch law. -

The Educator a Journal of Educational Matters

No.5/2019 EDITORIAL BOARD Editor-in-Chief: Comm. Prof. George Cassar Editorial members: Marco Bonnici, Christopher Giordano Design and Printing: Print Right Ltd Industry Road, Ħal Qormi - Malta Tel: 2125 0994 A publication of the Malta Union of Teachers © Malta Union of Teachers, 2019. ISSN: 2311-0058 CONTENTS ARTICLES A message from the President of the Malta Union of Teachers 1 A national research platform for Education Marco Bonnici A union for all seasons – the first century 3 of the Malta Union of Teachers (1919-2019) George Cassar Is it time to introduce a Quality Rating and Improvement System 39 (QRIS) for childcare settings in Malta to achieve and ensure high quality Early Childhood Education and Care experiences (ECEC)? Stephanie Curmi Social Studies Education in Malta: 61 A historical outline Philip E. Said How the Economy and Social Status 87 influence children’s attainment Victoria Mallia & Christabel Micallef Understanding the past with visual images: 101 Developing a framework for analysing moving-image sources in the history classroom Alexander Cutajar The Educator A journal of educational matters The objective of this annual, peer-reviewed journal is to publish research on any aspect of education. It seeks to attract contributions which help to promote debate on educational matters and present new or updated research in the field of education. Such areas of study include human development, learning, formal and informal education, vocational and tertiary education, lifelong learning, the sociology of education, the philosophy of education, the history of education, curriculum studies, the psychology of education, and any other area which is related to the field of education including teacher trade unionism. -

Remarks by Herman VAN ROMPUY, President of the European Council Following the Meeting with Mr Lawrence GONZI, Prime Minister of Malta

EUROPEAN COUNCIL Valletta, 13 January 2010 THE PRESIDENT PCE 06/10 Remarks by Herman VAN ROMPUY, President of the European Council following the meeting with Mr Lawrence GONZI, Prime Minister of Malta Herman Van ROMPUY, President of the European Council, visited Valletta today to attend a meeting with Mr Lawrence GONZI, Prime Minister of Malta. The following is a summary of his remarks made to journalists at the end of the meeting: "I am very pleased to be here in Valletta, for what has been a very productive discussion with Prime Minister Gonzi. Two immediate challenges face us, which will require the full engagement of the EU at the highest level: tackling the economic crisis and responding to the climate change. In this regard I have convened a meeting of EU Heads of State or Government, on 11 February, to examine these two issues. Securing full economic recovery in Europe is the key priority. We must overcome the challenges linked to this crisis whilst press ahead with the structural changes that we had embarked on under the Lisbon Strategy for jobs and growth. We must stimulate economic growth in order to finance our social model, to preserve what I call our "European Way of Life". On climate change, which will be the other big dossier the EU needs to tackle in the coming months. The EU must continue to be a driving force in this field. There has been a lot of criticism about the outcome of Copenhagen. Let us be clear. Without the EU, the results of Copenhagen would have been significantly less. -

MHA Newsletter March 2015

MHA Newsletter No. 2/2015 www.mha.org.au March 2015 Merħba! A warm welcome to all the members and Submerged Lowlands settled by early humans June 2014 friends of the Maltese Historical Association. much earlier than the present mainland. June 2014 Our February lecture on Maltese politics since 1947, by English scientists tested samples of sediment recovered Dr Albert Farrugia was well attended. As I do not by archaeologists from an underwater Mesolithic Stone usually have a great interest in politics, I did not think it Age site, off the coast of the Isle of Wight. They would be very interesting. I was pleased to be proved discovered DNA from einkorn, an early form of wheat. totally wrong: it was absolutely fascinating! A summary Archeologists also found evidence of woodworking, is contained in this newsletter. Our next lecture, on 17 cooking and flint tool manufacturing. Associated March, will be given by Professor Maurice Cauchi on the material, mainly wood fragments, was dated to history of Malta through its monuments. On 21 April, between 6010 BC and 5960 BC. These indicate just before the ANZAC day weekend, Mario Bonnici will Neolithic influence 400 years earlier than proximate discuss Malta’s involvement in the First World War. European sites and 2000 years earlier than that found on mainland Britain! In this newsletter you will also find an article about how an ancient site discovered off the coast of England may The nearest area known to have been producing change how prehistory is looked at; a number of einkorn by 6000 BC is southern Italy, followed by France interesting links; an introduction to Professor Cauchi’s and eastern Spain, who were producing it by at least lecture; coming events of interest; Nino Xerri’s popular 5900 BC. -

Politiker, Präsident Von Malta Biographie Barbara, Agatha (Zabbar

Report Title - p. 1 of 6 Report Title Adami, Edward Fenech (Birkirkara, Malta 1934-) : Politiker, Präsident von Malta Biographie 1994 Edward Fenech Adami besucht China. [ChiMal3] Barbara, Agatha (Zabbar, Malta 1923-2002 Zabbar) : Politikerin, Präsidentin von Malta Biographie 1985 Agatha Barbara besucht China. [ChiMal3] Borg, Joseph = Borg, Joe (Malta 1953-) : Politiker Biographie 2000 Joseph Borg besucht China. [ChiMal3] Chen, Zhimai (1908-1978) : Chinesischer Diplomat Biographie 1944 Chen Zhimai ist Counselor der chinesischen Botschaft in Washington, D.C. [ChiMal1] 1959-1966 Chen Zhimai ist Botschafter der chinesischen Botschaft in Canberra, Australien und in New Zealand. [ChiCan1,ChiAus2] 1969 Chen Zhimai ist Botschafter im Vatikan, Italien. [ChiMal1] 1971 Chen Zhimai ist Botschafter in Valletta, Malta. [ChiMal1] Cheng, Zhiping (um 1983) : Chinesischer Diplomat Biographie 1977-1983 Cheng Zhiping ist Botschafter der chinesischen Botschaft in Valletta, Malta. [ChiMal1] Falzon, Alfred J. (um 1982) : Maltesischer Diplomat Biographie 1981-1982 Alfred J. Falzon ist Botschafter der maltesischen Botschaft in Beijing. [ChiMal2] Forace, Joseph Lennard (Valletta, Malta 1925-2005) : Diplomat Biographie 1972-1978 Joseph Lennard ist Botschafter der maltesischen Botschaft in Beijing. [ChiMal2] Gonzi, Lawrence (Valletta 1953-) : Politiker, Premierminister von Malta Biographie 1996 Lawrence Gonzi besucht China. [ChiMal3] 2000 Lawrence Gonzi besucht China. [ChiMal3] Report Title - p. 2 of 6 Guo, Jiading (um 1993) : Chinesischer Diplomat Biographie 1983-1993 -

Trainers Manual

Together in Malta – Trainers Manual 1 Table of Contents List of Acronyms 3 Introduction 4 Proposed tools for facilitators of civic orientation sessions 6 What is civic orientation? 6 The Training Cycle 6 The principles of adult learning 7 Creating a respectful and safe learning space 8 Ice-breakers and introductions 9 Living in Malta 15 General information 15 Geography and population 15 Political system 15 National symbols 16 Holidays 17 Arrival and stay in Malta 21 Entry conditions 21 The stay in the country 21 The issuance of a residence permit 21 Minors 23 Renewal of the residence permit 23 Change of residence permit 24 Personal documents 24 Long-term residence permit in the EU and the acquisition of Maltese citizenship 24 Long Term Residence Permit 24 Obtaining the Maltese citizenship 25 Health 26 Access to healthcare 26 The National Health system 26 What public health services are provided? 28 Maternal and child health 29 Pregnancy 29 Giving Birth 30 Required and recommended vaccinations 30 Contraception 31 Abortion and birth anonymously 31 Women’s health protection 32 Prevention and early detection of breast cancer 32 Sexually transmitted diseases 32 Anti violence centres 33 FGM - Female genital mutilation 34 School life and adult education 36 IOM Malta 1 De Vilhena Residence, Apt. 2, Trejqet il-Fosos, Floriana FRN 1182, Malta Tel: +356 2137 4613 • Fax: +356 2122 5168 • E-mail: [email protected] • Internet: http://www.iom.int 2 Malta’s education system 36 School Registration 37 Academic / School Calendar 38 Attendance Control 38 -

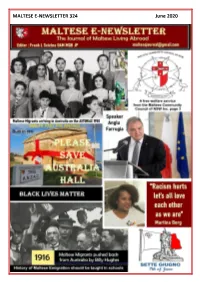

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 324 June 2020 1

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 324 June 2020 1 MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 324 June 2020 The Black Menace - When the Maltese Migrants were pushed back from Australia by Billy Hughes In 1916, Malta was a poor island, heavily caught up in WWI. It was “the nurse of the Mediterranean”, taking care of 80,000 wounded soldiers, a lot of them Australian. They were shipped in from Gallipoli and other European fronts, where Maltese men were fighting on the side of the British Empire themselves. For a small place, with only a little over 210,000 inhabitants, Malta went above and beyond, and many Australian returned soldiers were grateful. But that didn’t help the Maltese in 1916. When the Gange arrived in WA, Australia was in the grip of a referendum on conscription. Labor Prime Minister Billy Hughes, whose enthusiasm for the war had earned him the moniker “the little digger”, had become worried when the zeal to enlist had dropped off after alarming news of tens of thousands of deaths had been published. His solution was to try and see if he could force men to join the military, but for that he needed the permission of the Australian people. On the 28th of October 1916, there was to be a referendum that asked if they were okay with that. In the lead-up, the country had been split down the middle. Scared of conscription were the unions, who feared that with their members away at the front, their jobs would be taken over by women, or even worse, coloured people. -

The Current Situation of Gender Equality in Malta – Country Profile

15 The current situation of gender equality in Malta – Country Profile 2012 This country fiche was financed by, and prepared for the use of the European Commission, Directorate-General Justice, Unit D2 “Gender Equality” in the framework of the service contract managed by Roland Berger Strategy Consultants GmbH in partnership with ergo Unternehmenskommunikation GmbH & Co. KG. It does not necessarily reflect the opinion or position of the European Commission, Directorate-General Justice neither the Commission nor any person acting on its behalf is responsible for the use that might be made of the information contained in this publication. Table of Content 148 Foreword ......................................................................................................... 03 Management Summary .................................................................................... 04 1. How Maltese companies access the talent pool ........................................... 05 1.1 General participation of women and men in the labour market ............. 05 1.2 Part-time segregation of women and men ............................................. 06 1.3 Qualification level and choice of education of women and men .............. 08 1.4 Under-/overrepresentation of women and men in occupations or sectors – " Horizontal segregation"..................................................................... 09 1.5 Under-/overrepresentation of women and men in hierarchical levels – "Vertical segregation" ........................................................................... -

Archbishop Michael Gonzi, Dom Mintoff, and the End of Empire in Malta

1 PRIESTS AND POLITICIANS: ARCHBISHOP MICHAEL GONZI, DOM MINTOFF, AND THE END OF EMPIRE IN MALTA SIMON C. SMITH University of Hull The political contest in Malta at the end of empire involved not merely the British colonial authorities and emerging nationalists, but also the powerful Catholic Church. Under Archbishop Gonzi’s leadership, the Church took an overtly political stance over the leading issues of the day including integration with the United Kingdom, the declaration of an emergency in 1958, and Malta’s progress towards independence. Invariably, Gonzi and the Church found themselves at loggerheads with the Dom Mintoff and his Malta Labour Party. Despite his uncompromising image, Gonzi in fact demonstrated a flexible turn of mind, not least on the central issue of Maltese independence. Rather than seeking to stand in the way of Malta’s move towards constitutional separation from Britain, the Archbishop set about co-operating with the Nationalist Party of Giorgio Borg Olivier in the interests of securing the position of the Church within an independent Malta. For their part, the British came to accept by the early 1960s the desirability of Maltese self-determination and did not try to use the Church to impede progress towards independence. In the short-term, Gonzi succeeded in protecting the Church during the period of decolonization, but in the longer-term the papacy’s softening of its line on socialism, coupled with the return to power of Mintoff in 1971, saw a sharp decline in the fortunes of the Church and Archbishop Gonzi. Although less overt than the Orthodox Church in Cyprus, the power and influence of the Catholic Church in Malta was an inescapable factor in Maltese life at the end of empire. -

Unlocking the Female Potential Research Report

National Commission for the Promotion of Equality UNLOCKING THE FEMALE POTENTIAL RESEARCH Report Entrepreneurs and Vulnerable Workers in Malta & Gozo Economic Independence for the Maltese Female Analysing Inactivity from a Gender Perspective Gozitan Women in Employment xcv Copyright © National Commission for the Promotion of Equality (NCPE), 2012 National Commission for the Promotion of Equality (NCPE) Gattard House, National Road, Blata l-Bajda HMR 9010 - Malta Tel: +356 2590 3850 Email: [email protected] www.equality.gov.mt All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of research and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the author and publisher. Published in 2012 by the National Commission for the Promotion of Equality Production: Outlook Coop ISBN: 978-99909-89-44-1 2 National Commission for the Promotion of Equality FOREWORD Dear reader, NCPE’s commitment to eliminating gender equality in Malta comes forth again with this research exercise. As you will read in the following pages, through the European Social Fund project – ESF 3.47 Unlocking the Female Potential, NCPE has embarked on a mission to further understand certain realities that limit the involvement of women in the labour market. Throughout this research, we have sought to identify the needs of specific female target groups that make up the national context. -

IT-TLETTAX-IL LEĠIŻLATURA P.L. 4462 Raymond Scicluna Skrivan Tal-Kamra

IT-TLETTAX-IL LEĠIŻLATURA P.L. 4462 Dokument imqiegħed fuq il-Mejda tal-Kamra tad-Deputati fis-Seduta Numru 299 tas-17 ta’ Frar 2020 mill-Ministru fl-Uffiċċju tal-Prim Ministru, f’isem il-Ministru għall-Wirt Nazzjonali, l-Arti u Gvern Lokali. ___________________________ Raymond Scicluna Skrivan tal-Kamra BERĠA TA' KASTILJA - INVENTARJU TAL-OPRI TAL-ARTI 12717. L-ONOR. JASON AZZOPARDI staqsa lill-Ministru għall-Wirt Nazzjonali, l-Arti u l-Gvern Lokali: Jista' l-Ministru jwieġeb il-mistoqsija parlamentari 8597 u jgħid jekk hemmx u jekk hemm, jista’ jqiegħed fuq il-Mejda tal-Kamra l-Inventarju tal-Opri tal-Arti li hemm fil- Berġa ta’ Kastilja? Jista’ jgħid liema minnhom huma proprjetà tal-privat (fejn hu l-każ) u liema le? 29/01/2020 ONOR. JOSÈ HERRERA: Ninforma lill-Onor. Interpellant li l-ebda Opra tal-Arti li tagħmel parti mill-Kollezjoni Nazzjonali ġewwa l-Berġa ta’ Kastilja m’hi proprjetà tal-privat. għaldaqstant qed inpoġġi fuq il-Mejda tal-Kamra l-Inventarju tal-Opri tal-Arti kif mitlub mill- Onor. Interpellant. Seduta 299 17/02/2020 PQ 12717 -Tabella Berga ta' Kastilja - lnventarju tai-Opri tai-Arti INVENTORY LIST AT PM'S SEC Title Medium Painting- Madonna & Child with young StJohn The Baptist Painting- Portraits of Jean Du Hamel Painting- Rene Jacob De Tigne Textiles- banners with various coats-of-arms of Grandmasters Sculpture- Smiling Girl (Sciortino) Sculpture- Fondeur Figure of a lady (bronze statue) Painting- Dr. Lawrence Gonzi PM Painting- Francesco Buhagiar (Prime Minister 1923-1924) Painting- Sir Paul Boffa (Prime Minister 1947-1950) Painting- Joseph Howard (Prime Minister 1921-1923) Painting- Sir Ugo Mifsud (Prime Minister 1924-1927, 1932-1933) Painting- Karmenu Mifsud Bonnici (Prime Minister 1984-1987) Painting- Dom Mintoff (Prime Minister 1965-1958, 1971-1984) Painting- Lord Gerald Strickland (Prime Minister 1927-1932) Painting- Dr.