Issues in Translating Ellipsis with Particularreference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae Dr. A. Selvam

CURRICULUM VITAE DR. A. SELVAM Associate Professor Department of Plant Science Manonmaniam Sundaranar University Abishekapatti, Tirunelveli – 627012 Tamil Nadu, India Phone: +91-75985 51578 E-mail: [email protected] ACADEMIC QUALIFICATIONS Ph.D.: Botany, Centre for Advanced Studies in Botany, University of Madras, Chennai, India, 2001 M.Phil.: Botany (Mycology), Centre for Advanced Studies in Botany, University of Madras, Chennai, India, 1995. M.Sc.: Botany, Bharathiar University, Coimbatore, India B.Sc.: Botany, Bharathidasan University, Trichirappalli, India CITATION METRICS i) Journals published - National / International : 1/ 77 ii) Cumulative impact factor : 319.26 (JCR) iii) H-Index (Researcher ID) : 18 iv) H-Index (Google scholar) : 25 v) Citation : 1143 CAREER HISTORY Previous Positions Research Assistant Professor: Sino-Forest Applied Research Centre for Pearl River Delta Environment & Department of Biology, Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong SAR (2012 – 2016). Research Fellow: Sino-Forest Applied Research Centre for Pearl River Delta Environment, Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong SAR (2012). Research Associate, Sino-Forest Applied Research Centre for Pearl River Delta Environment, Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong SAR (2010 –2012). Post-Doctoral Visiting Research Scholar, Department of Biology, Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong SAR (2008 – 2010). Post-doctoral Fellow, Department of Microbiology and Biochemistry, National Taiwan University, Taiwan (2005 – 2008). Post-Doctoral Visiting Research Scholar, Department of Biology, Hong Kong Baptist University, 1 Hong Kong SAR (2004 – 2005). Lecturer, Department of Biotechnology, Periyar Maniammai College of Technology for Women, Vallam, Thanjavur, India (2003-2004). Project Assistant, Centre for Environmental Studies, Anna University, Chennai, India (2001 – 2003). Research Fellow (Jawaharlal Nehru memorial fund), Centre for Advanced Studies in Botany, University of Madras, Chennai (2000-2000). -

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K. Pandeeswaran No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Intercaste Marriage certificate not enclosed Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 2 AP-2 P. Karthigai Selvi No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Only one ID proof attached. Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 3 AP-8 N. Esakkiappan No.37/45E, Nandhagopalapuram, Above age Thoothukudi – 628 002. 4 AP-25 M. Dinesh No.4/133, Kothamalai Road,Vadaku Only one ID proof attached. Street,Vadugam Post,Rasipuram Taluk, Namakkal – 637 407. 5 AP-26 K. Venkatesh No.4/47, Kettupatti, Only one ID proof attached. Dokkupodhanahalli, Dharmapuri – 636 807. 6 AP-28 P. Manipandi 1stStreet, 24thWard, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Sivaji Nagar, and photo Theni – 625 531. 7 AP-49 K. Sobanbabu No.10/4, T.K.Garden, 3rdStreet, Korukkupet, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Chennai – 600 021. and photo 8 AP-58 S. Barkavi No.168, Sivaji Nagar, Veerampattinam, Community Certificate Wrongly enclosed Pondicherry – 605 007. 9 AP-60 V.A.Kishor Kumar No.19, Thilagar nagar, Ist st, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Chennai -600 019 10 AP-61 D.Anbalagan No.8/171, Church Street, Only one ID proof attached. Komathimuthupuram Post, Panaiyoor(via) Changarankovil Taluk, Tirunelveli, 627 761. 11 AP-64 S. Arun kannan No. 15D, Poonga Nagar, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Ch – 600 019 12 AP-69 K. Lavanya Priyadharshini No, 35, A Block, Nochi Nagar, Mylapore, Only one ID proof attached. Chennai – 600 004 13 AP-70 G. -

Sacredkuralortam00tiruuoft Bw.Pdf

THE HERITAGE OF INDIA SERIES Planned by J. N. FARQUHAR, M.A., D.Litt. (Oxon.), D.D. (Aberdeen). Right Reverend V. S. AZARIAH, LL.D. (Cantab.), Bishop of Dornakal. E. C. BEWICK, M.A. (Cantab.) J. N. C. GANGULY. M.A. (Birmingham), {TheDarsan-Sastri. Already published The Heart of Buddhism. K. J. SAUNDERS, M.A., D.Litt. (Cantab.) A History of Kanarese Literature, 2nd ed. E. P. RICE, B.A. The Samkhya System, 2nd ed. A. BERRDZDALE KEITH, D.C.L., D.Litt. (Oxon.) As"oka, 3rd ed. JAMES M. MACPHAIL, M.A., M.D. Indian Painting, 2nd ed. Principal PERCY BROWN, Calcutta. Psalms of Maratha Saints. NICOL MACNICOL, M.A. D.Litt. A History of Hindi Literature. F. E. KEAY, M.A. D.Litt. The Karma-Mlmamsa. A. BERRIEDALE KEITH, D.C.L., D.Litt. (Oxon.) Hymns of the Tamil aivite Saints. F. KINGSBURY, B.A., and G. E. PHILLIPS, M.A. Hymns from the Rigveda. A. A. MACDONELL, M.A., Ph.D., Hon. LL.D. Gautama Buddha. K. J. SAUNDERS, M.A., D.Litt. (Cantab.) The Coins of India. C. J. BROWN, M.A. Poems by Indian Women. MRS. MACNICOL. Bengali Religious Lyrics, Sakta. EDWARD THOMPSON, M.A., and A. M. SPENCER, B.A. Classical Sanskrit Literature, 2nd ed. A. BERRIEDALE KEITH, D.C.L., D.Litt. (Oxon.). The Music of India. H. A. POPLEY, B.A. Telugu Literature. P. CHENCHIAH, M.L., and RAJA M. BHUJANGA RAO BAHADUR. Rabindranath Tagore, 2nd ed. EDWARD THOMPSON, M.A. Hymns of the Alvars. J. S. M. HOOPER, M.A. (Oxon.), Madras. -

Divya Prabandham (The Divine Collection of Four Thousand)

Nammālvār A H U N D R E D M E A S U R E S O F T I M E Tiruviruttam Translated from the Tamil by Archana Venkatesan Contents About the Author Dedication A Note on Transliteration Praveśam: Entering the World of the Tiruviruttam Part I: A Hundred Measures of Time Part II: The Measure of Time Part III: Periyavāccān Piḷḷai’s Commentary on the Tiruviruttam Appendix 1: Index of Characters Appendix 2: Index of Motifs and Typology of Verses Appendix 3: Indices of Myths, Places and Names Footnotes Praveśam: Entering the World of the Tiruviruttam Appendix 2 Annotations to Nammālvār’s Tiruviruttam Notes Glossary Bibliography Acknowledgements Read more Follow Penguin Copyright Page PENGUIN CLASSICS A HUNDRED MEASURES OF TIME ARCHANA VENKATESAN is associate professor of Comparative Literature and Religious Studies at the University of California, Davis. She has received numerous grants, including fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, National Endowment for the Humanities, American Institute of Indian Studies and Fulbright. Her research interests are in the intersection of text and performance in south India, as well as in the translation of early and medieval Tamil poetry into English. She is the author of The Secret Garland: Āṇṭāḷ’s Tiruppāvai and Nācciyār Tirumoli (2010), and is collaborating with Francis Clooney of Harvard University on an English translation of Nammālvār’s Tiruvāymoli. for my teachers A Note on Transliteration I have transliterated Tamil words according to the conventions of the Tamil Lexicon. Sanskrit-derived Tamil words are generally in their most easily recognizable form—so, Mādhavan instead of Mātavan. -

Timeline-Of-Tamil-History.Pdf

Timeline of Tamil History Copyright © 2015 T. Moodali ISBN 978-0-620-66782-1 First edition, 2015 Published by T. Moodali P.O. Box 153 Desainagar South Africa 4405 Email: [email protected] Website: www.tamilhumanism.com Facebook: Thiru Moodali Facebook group: Tamil Humanism Facebook page: Tamil Humanism Twitter: @Tamil Humanism Linkin: Thiru Moodali All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. DEDICATED To Tamil Humanists The Tamil Humanist symbol A is the first letter and with other letters forms the Tamil alphabet. It is also the first letter of the word ‘Anbe’. ‘Anbe’ means love. So the letter A is a symbol of love. The circle around the letter A symbolizes the earth. This emphasizes the universality of love and the philosophy of Tamil Humanism. The shape of the heart around the earth is a symbol of love and healthy living. The two rings overlapping together is a letter from the Indus Valley script. It is the symbol of humanism, human unity and cooperation. This Tamil Humanist symbol defines Tamil Humanism’s unique identity and its philosophy’s continued existence since the inception of the Indus Valley civilization to the present times. Red, Black and yellow are traditional Tamil colours. Blue is the colour of the earth from space. CONTENTS 1. Pre-historic period of Tamil Independence 2. Sangam period of Tamil Independence (600 BC – 300 AD) 3. -

English 710-882

AN ETHNOMUSICOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE ON KANIYAN KOOTHU Aaron J. Paige This paper will analyze some of the strategies by which Kaniyans, a minority com- munity from the Southern districts of Tamil Nadu, use music as a vehicle to negoti- ate, reconcile, and understand social, cultural, and economic change. Kaniyan Koothu performances are generally commissioned for kodai festivals, during which Kaniyans sing lengthy ballads. These stories vary locally from village to village and recount the adventures, exploits, and virtues of gods and goddesses specific to the area and community in which they are worshipped. While these narratives are en- tertaining in their own right, they also serve as springboards for subjective compari- son and interpretation. Kaniyans thus, transform mythological legends into modern social commentary. In a world perceived to be growing increasingly complicated by globalization and modernization, these folk musicians openly voice in performance both their concern for the loss of traditional values and their trepidation that Tamil culture, tamizh panpaadu – particularly village culture, gramiya panpaadu – are gradually being displaced by foreign principles, products, and technologies. In con- tradistinction to this conservative rhetoric, the Kaniyans, in recent years, have made major reformations to their own musical practice. Using specific textual examples, the first part of this paper will look at the ways in which musicians’ semi-improvised narratives foster solidarity under the rubric of a shared Tamil language and cultural identity. The second part of this paper, by way of musical examples, will attempt to illuminate how these same musicians are engaged in redefining and reformulating their musical tradition through the appropriation and integration of rhythmic models characteristic of Carnatic drumming. -

Poetics of Place in Early Tamil Literature by Vangal N Muthukumar

Poetics of place in early Tamil literature by Vangal N Muthukumar A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in South and Southeast Asian Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor George L. Hart, Chair Professor Munis D. Faruqui Professor Robert P. Goldman Professor Bonnie C. Wade Fall 2011 Poetics of place in early Tamil literature Copyright 2011 by Vangal N Muthukumar 1 Abstract Poetics of place in early Tamil literature by Vangal N Muthukumar Doctor of Philosophy in South and Southeast Asian Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor George L. Hart, Chair In this dissertation, I discuss some representations of place in early (ca. 100 CE - 300 CE) Tamil poetry collectively called caṅkam literature. While previous research has emphasized the im- portance of place as landscape imagery in these poems, it has seldom gone beyond treating landscape / place as symbolic of human emotionality. I argue that this approach does not ad- dress the variety in the representation of place seen in this literature. To address this the- oretical deficiency, I study place in caṅkam poetry as having definite ontological value and something which is immediately cognized by the senses of human perception. Drawing from a range of texts, I will argue that in these poems, the experience of place emerges in a di- alogic between the human self and place - a dialogic which brings together sensory experi- ence, perception, memory, and various socio-cultural patterns; place, in these poems, is not as much an objective geographical entity as it is the process of perception itself. -

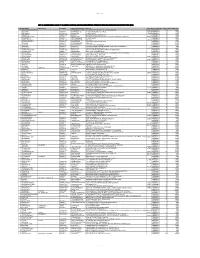

Officials from the State of Tamil Nadu Trained by NIDM During the Year 209-10 to 2014-15

Officials from the state of Tamil Nadu trained by NIDM during the year 209-10 to 2014-15 S.No. Name Designation & Address City & State Department 1 Shri G. Sivakumar Superintending National Highways 260 / N Jawaharlal Nehru Salai, Chennai, Tamil Engineer, Roads & Jaynagar - Arumbakkam, Chennai - 600166, Tamil Nadu Bridges Nadu, Ph. : 044-24751123 (O), 044-26154947 (R), 9443345414 (M) 2 Dr. N. Cithirai Regional Joint Director Animal Husbandry Department, Government of Tamil Chennai, Tamil (AH), Animal husbandry Nadu, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, Ph. : 044-27665287 (O), Nadu 044-23612710 (R), 9445001133 (M) 3 Shri Maheswar Dayal SSP, Police Superintending of Police, Nagapattinam District, Tamil Nagapattinam, Nadu, Ph. : 04365-242888 (O), 04365-248777 (R), Tamil Nadu 9868959868 (M), 04365-242999 (Fax), Email : [email protected] 4 Dr. P. Gunasekaran Joint Director, Animal Animal Husbandary, Thiruvaruru, Tamil Nadu, Ph. : Thiruvarur, Tamil husbandary 04366-205946 (O), 9445001125 (M), 04366-205946 Nadu (Fax) 5 Shri S. Rajendran Dy. Director of Department of Agriculture, O/o Joint Director of Ramanakapuram, Agriculture, Agriculture Agriculture, Ramanakapuram (Disa), Tamil Nadu, Ph. : Tamil Nadu 04567-230387 (O), 04566-225389 (R), 9894387255 (M) 6 Shri R. Nanda Kumar Dy. Director of Statistics, Department of Economics & Statistics, DMS Chennai, Tamil Economics & Statistics Compound, Thenampet, Chennai - 600006, Tamil Nadu Nadu, Ph. : 044-24327001 (O), 044-22230032 (R), 9865548578 (M), 044-24341929 (Fax), Email : [email protected] 7 Shri U. Perumal Executive Engineer, Corporation of Chennai, Rippon Building, Chennai - Chennai, Tamil Municipal Corporation 600003, Ph. : 044-25361225 (O), 044-65687366 (R), Nadu 9444009009 (M), Email : [email protected] National Institute of Disaster Management (NIDM) Trainee Database is available at http://nidm.gov.in/trainee2.asp 58 Officials from the state of Tamil Nadu trained by NIDM during the year 209-10 to 2014-15 8 Shri M. -

The Tamil Concept of Love

The Tamil Concept Of love First Edition 1962 Published by The South India Saiva Siddhanta Works Publishing Society, Tirunelvely, 1962 2 Manicka Vizhumiyangal - 16 The Tamil Concept of Love 3 PREFACE I deem it my sincere duty to present before the scholars of the world the noble principles of Aham Literature whose origin is as old as Tamil language itself and whose influence on all kinds of Tamil literature of all periods is incalculable. An elementary knowledge of Aham is indeed essential even for a beginner in Tamil. Without its study, Tamil culture and civilisation will be a sealed book. Love is no doubt the common theme of any literature in any language. The selective nature of the love-aspects, the impersonal and algebraic form of the characters and the universal and practical treatment of the subject are the differentiating points of Ahattinai. What is the impulse behind the creation of Aham literature? The unity of the family is the bed-rock of the unity of the world. The achievement of that conjugal unity depends upon the satisfaction of the sexual congress between the rightful lovers in youthhood. Dissatisfaction unconsciously disintegrates the family. There will be few problems in society, religion and politics, if family life is a contented one and the husband and wife pay high regard to each other’s sexual hunger. Therefore sex education is imperative to every young man and woman before and after marriage. How to educate them? The ancient Tamils saw in literature an effective and innocent means for instructing boys and girls in sexual principles and sexual experiences and with 4 Manicka Vizhumiyangal - 16 that noble motive created a well-defined literature called Ahattinai with inviolable rules. -

Unpaid Data 1

Unpaid_Data_1 LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS LIABLE TO TRANSFER OF UNPAID AND UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND DIVIDEND TO INVESTOR EDUCATION PROTECTION FUND (IEPF) S.No First Name Middle Name Last Name Father/Husband Name Address PINCodeFolio NumberNo of SharesAmount Due(in Rs.) 1 RADHAKRISHNANTSSSD SRITSSSDURAISAMY CO-OPERATIVE STORES LTD., VIRUDHUNAGAR 626001 P00000011 15 13500 2 MUTHIAH NADAR M SRIMARIMUTHU THIRUTHANGAL SATTUR TALUK 626130 P00000014 2 1800 3 SHUNMUGA NADAR GAS SRISUBBIAH THOOTHUKUDI 628001 P00000015 11 9900 4 KALIAPPA NADAR NAA SRIAIYA ELAYIRAMPANNAI, SATTUR VIA P00000023 2 1800 5 SANKARALINGAM NADAR A SRIARUMUGA C/O SRI.S.S.M.MAYANDI NADAR, 24-KALMANDAPAM ROAD, CHENNAI 600013 P00000024 2 1800 6 GANAPATHY NADAR P SRIPERIAKUMAR THOOTHUKUDI P00000046 10 9000 7 SANKARALINGA NADAR ASS SRICHONAMUTHU SIVAKASI 626123 P00000050 1 900 8 SHUNMUGAVELU NADAR VS SRIVSUBBIAH 357-MOGUL STREET, RANGOON P00000084 11 9900 9 VELLIAH NADAR S SRIVSWAMIDASS RANGOON P00000090 3 2700 10 THAVASI NADAR KP SRIKPERIANNA 40-28TH STREET, RANGOON P00000091 2 1800 11 DAWSON NADAR A NAPPAVOO C/O SRI.N.SAMUEL, PRASER STREET, POST OFFICE, RANGOON-1 P00000095 1 900 12 THIRUVADI NADAR R RAMALINGA KALKURICHI, ARUPPUKOTTAI 626101 P00000096 10 9000 13 KARUPPANASAMY NADAR ALM MAHALINGA KASI VISWANATHAN NORTH STREET, KUMBAKONAM P00000097 10 9000 14 PADMAVATHI ALBERT SRIPEALBERT EAST GATE, SAWYERPURAM P00000101 40 36000 15 KANAPATHY NADAR TKAA TKAANNAMALAI C/O SRI.N.S.S.CHINNASAMY NADAR, CHITRAKARA VEEDHI, MADURAI P00000105 5 4500 16 MUTHUCHAMY NADAR PR PRAJAKUMARU EAST MASI STREET, MADURAI P00000107 10 9000 17 CHIDAMBARA NADAR M VMARIAPPA 207-B EAST MARRET STREET, MADURAI 625001 P00000108 5 4500 18 KARUPPIAH NADAR KKM LATE SRIKKMUTHU EMANESWARAM, PARAMAKUDI T.K. -

Eva Maria Wilden Manuscript, Print and Memory Studies in Manuscript Cultures

Eva Maria Wilden Manuscript, Print and Memory Studies in Manuscript Cultures Edited by Michael Friedrich Harunaga Isaacson Jörg B. Quenzer Volume 3 Eva Maria Wilden Manuscript, Print and Memory Relics of the Caṅkam in Tamilnadu ISBN 978-3-11-034089-1 e-ISBN 978-3-11-035276-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-038779-7 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2014 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/München/Boston Typesetting: Dörlemann Satz, Lemförde Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com To the memory of T. V. Gopal Iyer and T. S. Gangadharan, men of deep learning and dedication, two in the long line of Tamil Brahmin scholars and teachers Preface After more than ten years of searching, digitising and editing manuscripts the series of critical editions published by the Caṅkam project of the École Fran- çaise d’Extrême Orient in Pondicherry is now complemented by an introductory volume of historical studies into the transmission of the texts and their witnesses. A three-years stay, from July 2008 to June 2011, in the Hamburg Research Group entitled “Textual Variance in Dependence on the Medium”, graciously funded by the German Research Association, enabled me to win the necessary distance from my ongoing labour in the jungle of actual textual variation to try to give an outline of the larger picture for one instance of a phenomenon known in cultural history, namely the formation, deformation and reformation of a literary canon over a period of almost two thousand years. -

A Primer of Tamil Literature

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com A PRIMER OF TAMIL LITERATURE BY iA. S. PURNALINGAM PILLAI, b.a., Professor of English, St. Michael's College, Coimbatore. PRINTED AT THE ANANDA PRESS. 1904. Price One Rupee or Two Shillings. (RECAP) .OS FOREWORD. The major portion of this Primer was written at Kttaiyapuram in 1892, and the whole has lain till now in manuscript needing my revision and retouching. Owing to pressure of work in Madras, I could spare no time for it, and the first four years of my service at Coim- batore were so fully taken up with my college work that I had hardly breathing time for any literary pursuit. The untimely death of Mr. V. G. Suryanarayana Sastriar, B.A., — my dear friend and fellow-editor of J nana Bodhini — warned me against further delay, and the Primer in its present form is the result of it. The Age of the Sangams was mainly rewritten, while the other Ages were merely touched up. In the absence of historical dates — for which we must wait, how long we do not know — I have tried my best with the help of the researches already made to divide, though roughly, twenty centuries of Tamil Literature into Six Ages, each Age being distinguished by some great movement, literary or religious. However .defective it may be in point of chronology, the Primer will justify its existence if it gives foreigners and our young men in the College classes whose mother-tongue is Tamil, an idea of the world of Tamil books we have despite the ravages of time and white-ants, flood and fire, foreign malignity and native lethargy.